PTERIDOLOGIST 2011 Contents: Volume 5 Part 4, 2011 a Modern Glazed Case A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kells Bay Nursery

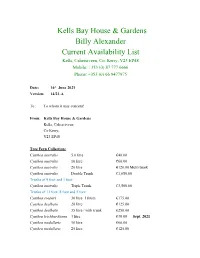

Kells Bay House & Gardens Billy Alexander Current Availability List Kells, Cahersiveen, Co. Kerry, V23 EP48 Mobile: +353 (0) 87 777 6666 Phone: +353 (0) 66 9477975 Date: 16th June 2021 Version: 14/21-A To : To whom it may concern! From: Kells Bay House & Gardens Kells, Caherciveen Co Kerry, V23 EP48 Tree Fern Collection: Cyathea australis 5.0 litre €40.00 Cyathea australis 10 litre €60.00 Cyathea australis 20 litre €120.00 Multi trunk Cyathea australis Double Trunk €1,650.00 Trunks of 9 foot and 1 foot Cyathea australis Triple Trunk €3,500.00 Trunks of 11 foot, 8 foot and 5 foot Cyathea cooperi 30 litre 180cm €175.00 Cyathea dealbata 20 litre €125.00 Cyathea dealbata 35 litre / with trunk €250.00 Cyathea leichhardtiana 3 litre €30.00 Sept. 2021 Cyathea medullaris 10 litre €60.00 Cyathea medullaris 25 litre €125.00 Cyathea medullaris 35 litre / 20-30cm trunk €225.00 Cyathea medullaris 45 litre / 50-60cm trunk €345.00 Cyathea tomentosisima 5 litre €50.00 Dicksonia antarctica 3.0 litre €12.50 Dicksonia antarctica 5.0 litre €22.00 These are home grown ferns naturalised in Kells Bay Gardens Dicksonia antarctica 35 litre €195.00 (very large ferns with emerging trunks and fantastic frond foliage) Dicksonia antarctica 20cm trunk €65.00 Dicksonia antarctica 30cm trunk €85.00 Dicksonia antarctica 60cm trunk €165.00 Dicksonia antarctica 90cm trunk €250.00 Dicksonia antarctica 120cm trunk €340.00 Dicksonia antarctica 150cm trunk €425.00 Dicksonia antarctica 180cm trunk €525.00 Dicksonia antarctica 210cm trunk €750.00 Dicksonia antarctica 240cm trunk €925.00 Dicksonia antarctica 300cm trunk €1,125.00 Dicksonia antarctica 360cm trunk €1,400.00 We have lots of multi trunks available, details available upon request. -

Download Document

African countries and neighbouring islands covered by the Synopsis. S T R E L I T Z I A 23 Synopsis of the Lycopodiophyta and Pteridophyta of Africa, Madagascar and neighbouring islands by J.P. Roux Pretoria 2009 S T R E L I T Z I A This series has replaced Memoirs of the Botanical Survey of South Africa and Annals of the Kirstenbosch Botanic Gardens which SANBI inherited from its predecessor organisations. The plant genus Strelitzia occurs naturally in the eastern parts of southern Africa. It comprises three arborescent species, known as wild bananas, and two acaulescent species, known as crane flowers or bird-of-paradise flowers. The logo of the South African National Biodiversity Institute is based on the striking inflorescence of Strelitzia reginae, a native of the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal that has become a garden favourite worldwide. It sym- bolises the commitment of the Institute to champion the exploration, conservation, sustain- able use, appreciation and enjoyment of South Africa’s exceptionally rich biodiversity for all people. J.P. Roux South African National Biodiversity Institute, Compton Herbarium, Cape Town SCIENTIFIC EDITOR: Gerrit Germishuizen TECHNICAL EDITOR: Emsie du Plessis DESIGN & LAYOUT: Elizma Fouché COVER DESIGN: Elizma Fouché, incorporating Blechnum palmiforme on Gough Island PHOTOGRAPHS J.P. Roux Citing this publication ROUX, J.P. 2009. Synopsis of the Lycopodiophyta and Pteridophyta of Africa, Madagascar and neighbouring islands. Strelitzia 23. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria. ISBN: 978-1-919976-48-8 © Published by: South African National Biodiversity Institute. Obtainable from: SANBI Bookshop, Private Bag X101, Pretoria, 0001 South Africa. -

Bruxner Park Flora Reserve Working Plan

Bruxner Park Flora Reserve Working Plan Working Plan for Bruxner Park Flora Reserve No 3 Upper North East Forest Agreement Region North East Region Contents Page 1. DETAILS OF THE RESERVE 2 1.1 Introduction 2 1.2 Location 2 1.3 Key Attributes of the Reserve 2 1.4 General Description 2 1.5 History 6 1.6 Current Usage 8 2. SYSTEM OF MANAGEMENT 9 2.1 Objectives of Management 9 2.2 Management Strategies 9 2.3 Management Responsibility 11 2.4 Monitoring, Reporting and Review 11 3. LIST OF APPENDICES 11 Appendix 1 Map 1 Locality Appendix 1 Map 2 Cadastral Boundaries, Forest Types and Streams Appendix 1 Map 3 Vegetation Growth Stages Appendix 1 Map 4 Existing Occupation Permits and Recreation Facilities Appendix 2 Flora Species known to occur in the Reserve Appendix 3 Fauna records within the Reserve Y:\Tourism and Partnerships\Recreation Areas\Orara East SF\Bruxner Flora Reserve\FlRWP_Bruxner.docx 1 Bruxner Park Flora Reserve Working Plan 1. Details of the Reserve 1.1 Introduction This plan has been prepared as a supplementary plan under the Nature Conservation Strategy of the Upper North East Ecologically Sustainable Forest Management (ESFM) Plan. It is prepared in accordance with the terms of section 25A (5) of the Forestry Act 1916 with the objective to provide for the future management of that part of Orara East State Forest No 536 set aside as Bruxner Park Flora Reserve No 3. The plan was approved by the Minister for Forests on 16.5.2011 and will be reviewed in 2021. -

Dock and Crop Images

orders: [email protected] (un)subscribe: [email protected] Current Availability for September 25, 2021 Dock and Crop images Click any thumbnail below for the slideshow of what we shipped this past week: CYCS ARE RED HOT GIANT GLOSSY LEAVES BLUE MOONSCAPE SUCCULENT BLUE LEAVES SUCCULENT ORANGE LEAVES SPECKLED LEAVES CYCS ARE RED HOT RED SUNSETSCAPE Jeff's updates - 9/16 dedicated this week's favorites Chimi's favorite climbing structure 4FL = 4" pot, 15 per flat 10H = 10" hanging basket n = new to the list ys = young stock 6FL = 6" pot, 6 per flat 10DP = 10" Deco Pot, round b&b = bud and bloom few = grab 'em! QT= quart pot, 12 or 16 per flat nb = no bloom * = nice ** = very nice Quarts - 12 per flat, Four Inch - 15 per flat, no split flats, all prices NET code size name comments comments 19406 4FL Acalypha wilkesiana 'Bronze Pink' ** Copper Plant-colorful lvs 12210 QT Acorus gramineus 'Ogon' ** lvs striped creamy yellow 19069 4FL Actiniopteris australis ** Eyelash Fern, Ray Fern 17748 4FL Adiantum hispidulum ** Rosy Maidenhair 17002 4FL Adiantum raddianum 'Microphyllum' ** extremely tiny leaflets 21496 4FL Adromischus filicaulis (cristatus?) ** Crinkle Leaf 16514 4FL Aeonium 'Kiwi' ** tricolor leaves 13632 QT Ajuga 'Catlin's Giant' ** huge lvs, purple fls 13279 QT Ajuga pyramidalis 'Metallica Crispa' ** crinkled leaf 17560 4FL Aloe vera * Healing Aloe, a must-have 13232 QT Anthericum sanderii 'Variegated' *b&b grassy perennial 13227 QT Asparagus densiflorus 'Meyer's' ** Foxtail Fern 19161 4FL Asplenium 'Austral Gem' -

WINTER 1998 TH In*Vi'i§

a i 9dardy'fernSFoundationm Editor Sue Olsen VOLUME 7 NUMBER 1 WINTER 1998 TH in*vi'i§ Presidents’ Message: More Inside... Jocelyn Horder and Anne Holt, Co-Presidents Polypodium polypodioides.2 Greetings and best wishes for a wonderful fern filled 1998. At this winter time of year Deer Problems.2 many of our hardy ferns offer a welcome evergreen touch to the garden. The varied textures are particularly welcome in bare areas. Meanwhile ferns make wonderful Book Review.3 companions to your early spring flowering bulbs and blooming plants. Since we are Exploring Private having (so far) a mild winter continue to control the slugs and snails that are lurking European Gardens Continued.4 around your ferns and other delicacies. Mr. Gassner Writes.5 Don’t forget to come to the Northwest Flower and Garden show February 4-8 to enjoy Notes from the Editor.5 the colors, fragrances and fun of spring. The Hardy Fern Foundation will have a dis¬ play of ferns in connection with the Rhododendron Species Botanical Garden. Look for Fem Gardens of the Past and a Garden in Progress.6-7 booth #6117-9 on the fourth floor of the Convention Center where we will have a dis¬ play of ferns, list of fern sources, cultural information and as always persons ready to Fem Finding in the Hocking Hills.8-10 answer your questions. Anyone interested in becoming more involved with the Hardy Blechnum Penna-Marina Fern Foundation will have a chance to sign up for volunteering in the future. Little Hard Fem.10 We are happy to welcome the Coastal Botanical Garden in Maine as a new satellite The 1997 HFF garden. -

A.N.P.S.A. Fern Study Group Newsletter Number 125

A.N.P.S.A. Fern Study Group Newsletter Number 125 ISSN 1837-008X DATE : February, 2012 LEADER : Peter Bostock, PO Box 402, KENMORE , Qld 4069. Tel. a/h: 07 32026983, mobile: 0421 113 955; email: [email protected] TREASURER : Dan Johnston, 9 Ryhope St, BUDERIM , Qld 4556. Tel 07 5445 6069, mobile: 0429 065 894; email: [email protected] NEWSLETTER EDITOR : Dan Johnston, contact as above. SPORE BANK : Barry White, 34 Noble Way, SUNBURY , Vic. 3429. Tel: 03 9740 2724 email: barry [email protected] From the Editor Peter Hind has contributed an article on the mystery resurrection of Asplenium parvum in his greenhouse. Peter has also provided meeting notes on the reclassification of filmy ferns. From Kylie, we have detail on the identification, life cycle, and treatment of coconut or white fern scale - Pinnaspis aspidistra , which sounds like a nasty problem in the fernery. (Fortunately, I haven’t encountered it.) Thanks also to Dot for her contributions to the Sydney area program and a meeting report and to Barry for his list of his spore bank. The life of Fred Johnston is remembered by Kyrill Taylor. Program for South-east Queensland Region Dan Johnston Sunday, 4 th March, 2012 : Excursion to Upper Tallebudgera Creek. Rendezvous at 9:30am at Martin Sheil Park on Tallebudgera Creek almost under the motorway. UBD reference: Map 60, B16. Use exit 89. Sunday, 1 st April, 2012 : Meet at 9:30am at Claire Shackel’s place, 19 Arafura St, Upper Mt Gravatt. Subject: Fern Propagation. Saturday, 5 th May – Monday, 7th May, 2012. -

Nzbotsoc No 107 March 2012

NEW ZEALAND BOTANICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER NUMBER 107 March 2012 New Zealand Botanical Society President: Anthony Wright Secretary/Treasurer: Ewen Cameron Committee: Bruce Clarkson, Colin Webb, Carol West Address: c/- Canterbury Museum Rolleston Avenue CHRISTCHURCH 8013 Subscriptions The 2012 ordinary and institutional subscriptions are $25 (reduced to $18 if paid by the due date on the subscription invoice). The 2012 student subscription, available to full-time students, is $12 (reduced to $9 if paid by the due date on the subscription invoice). Back issues of the Newsletter are available at $7.00 each. Since 1986 the Newsletter has appeared quarterly in March, June, September and December. New subscriptions are always welcome and these, together with back issue orders, should be sent to the Secretary/Treasurer (address above). Subscriptions are due by 28 February each year for that calendar year. Existing subscribers are sent an invoice with the December Newsletter for the next years subscription which offers a reduction if this is paid by the due date. If you are in arrears with your subscription a reminder notice comes attached to each issue of the Newsletter. Deadline for next issue The deadline for the June 2012 issue is 25 May 2012. Please post contributions to: Lara Shepherd Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa P.O. Box 467 Wellington Send email contributions to [email protected]. Files are preferably in MS Word, as an open text document (Open Office document with suffix “.odt”) or saved as RTF or ASCII. Macintosh files can also be accepted. Graphics can be sent as TIF JPG, or BMP files; please do not embed images into documents. -

Index Seminum 2015 List of Seeds for Exchange

Index Seminum 2015 List of seeds for exchange Glasgow Botanic Gardens 730 Great Western Road Glasgow, G12 OUE Scotland, United Kingdom History of Glasgow Botanic Gardens The Botanic Gardens were founded on an 8-acre site at the West End of Sauchiehall Street at Sandyford in 1817. This was through the initiative of Thomas Hopkirk of Dalbeth who gave his own plant collection to form the nucleus of the new garden. It was run by the Royal Botanical Institution of Glasgow and an agreement was reached with Glasgow University to provide facilities for teaching, including supply of plants for botanical and medical classes. Professor William J. Hooker, Regius Professor of Botany at the University of Glasgow (1820-41), took an active part in the development of the Gardens, which became well known in botanical circles throughout the world. The early success led to expansion and the purchase of the present site, at Kelvinside, in 1842. At the time entry was mainly restricted to members of the Royal Botanical Institution and their friends although later the public were admitted on selected days for the princely sum of one penny. The Kibble Palace which houses the national tree fern collection was originally a private conservatory located at Coulport by Loch Long. It was moved to its present site in 1873 and originally used as a concert venue and meeting place, hosting speakers such as Prime Ministers Disraeli and Gladstone. Increasing financial difficulties led to the Gardens being taken over by the then Glasgow Corporation in 1891 on condition they continued as a Botanic Garden and maintained links with the University. -

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska United States Forest Service R10-RG-182 Department of Alaska Region June 2010 Agriculture Ferns abound in Alaska’s two national forests, the Chugach and the Tongass, which are situated on the southcentral and southeastern coast respectively. These forests contain myriad habitats where ferns thrive. Most showy are the ferns occupying the forest floor of temperate rainforest habitats. However, ferns grow in nearly all non-forested habitats such as beach meadows, wet meadows, alpine meadows, high alpine, and talus slopes. The cool, wet climate highly influenced by the Pacific Ocean creates ideal growing conditions for ferns. In the past, ferns had been loosely grouped with other spore-bearing vascular plants, often called “fern allies.” Recent genetic studies reveal surprises about the relationships among ferns and fern allies. First, ferns appear to be closely related to horsetails; in fact these plants are now grouped as ferns. Second, plants commonly called fern allies (club-mosses, spike-mosses and quillworts) are not at all related to the ferns. General relationships among members of the plant kingdom are shown in the diagram below. Ferns & Horsetails Flowering Plants Conifers Club-mosses, Spike-mosses & Quillworts Mosses & Liverworts Thirty of the fifty-four ferns and horsetails known to grow in Alaska’s national forests are described and pictured in this brochure. They are arranged in the same order as listed in the fern checklist presented on pages 26 and 27. 2 Midrib Blade Pinnule(s) Frond (leaf) Pinna Petiole (leaf stalk) Parts of a fern frond, northern wood fern (p. -

Asplenium Bulbiferum

Asplenium bulbiferum COMMON NAME Hen and chicken fern, pikopiko, mother spleenwort SYNONYMS Asplenium marinum var. bulbifera (G.Forst.) F.Muell.; Caenopteris bulbifera (G.Forst.) Desv.; FAMILY Aspleniaceae AUTHORITY Asplenium bulbiferum G. Forst. FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Native ENDEMIC TAXON Yes Stokes Valley. Aug 2006. Bulbil on bulbil. ENDEMIC GENUS Photographer: Jeremy Rolfe No ENDEMIC FAMILY No STRUCTURAL CLASS Ferns NVS CODE ASPBUL sorus. Feb 1981. Photographer: Jeremy Rolfe CHROMOSOME NUMBER 2n = 144 CURRENT CONSERVATION STATUS 2012 | Not Threatened PREVIOUS CONSERVATION STATUSES 2009 | Not Threatened 2004 | Not Threatened DISTRIBUTION Endemic. North, South, Stewart and Chatham Islands HABITAT Coastal to subalpine. Usually in lowland forest where it is a common species of the ground-layer, especially in high rainfall areas. Commonly associated with riparian forest, and as a species of base-rich substrates. Frequently sympatric and so commonly forming hybrids with other asplenia. It is commonly sympatric with A. gracillimum Colenso. FEATURES Rhizome short, stout, erect, bearing ovate scales up to 15 × 5 mm. Stipes 50-300 mm long, brown on underside, green above, stout, covered in small brown ovate scales. Laminae lanceolate to elliptic, 0.15-1.20 m, 70-300 mm, bi- to tripinnate, sometimes bearing bulbils. Raches pale green to yellow-green, scaly, prominently grooved, usually bulbiferous. Pinnae 15-30 (or more) pairs, ovate to narrowly ovate, acuminate, shortly stalked, 30-200 × 10-50 mm, scaly on underside, basal pair pointing downwards when fresh. Secondary pinnae sessile or shortly stalked, very narrowly elliptic to ovate or elliptic, obtuse, deeply serrate or sometimes almost pinnate, decreasing in size from base to apex, basal acroscopic pinnule often enlarged (up to 40 × 10 mm). -

2011 Biodiversity Snapshot. Guernsey Appendices

UK Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies: 2011 Biodiversity snapshot. Guernsey: Appendices. Author: Dr Charles David Guernsey Biological Records Centre, States of Guernsey Environment Department & La Societe Guernesiaise. More information available at: www.biologicalrecordscentre.gov.gg This section includes a series of appendices that provide additional information relating to that provided in the Guernsey chapter of the publication: UK Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies: 2011 Biodiversity snapshot. All information relating to Guernsey is available at http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-5743 The entire publication is available for download at http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-5821 Commissioned by the States of Guernsey Environment Department for the Joint Nature Conservation Committee Prepared by Dr C T David Guernsey Biological Records Centre August 2010 1 Contents Appendix 1: Bailiwick of Guernsey – Location and Introduction ............................. 3 Location, Area, Number of Islands, Population 3 Topography 4 Main economic sectors 4 Constitutional Position 4 Appendix 2: Multilateral Environmental Agreements. ............................................... 5 Appendix 3: National Legislation ................................................................................ 8 Planning 8 Ancient Monuments 8 Coast and beaches 8 Land 8 Fauna 8 Flora 9 Trees 9 Import/export 9 Marine environment 9 Waste 9 Water 9 Appendix 4: National Strategies ................................................................................ 11 Appendix -

Summer 2010 Hardy Fern Foundation Quarterly Ferns to Our Collection There

THE HARDY FERN FOUNDATION P.O. Box 3797 Federal Way, WA 98063-3797 Web site: www.hardyfems.org The Hardy Fern Foundation was founded in 1989 to establish a comprehen¬ sive collection of the world’s hardy ferns for display, testing, evaluation, public education and introduction to the gardening and horticultural community. Many rare and unusual species, hybrids and varieties are being propagated from spores and tested in selected environments for their different degrees of hardiness and ornamental garden value. The primary fern display and test garden is located at, and in conjunction with, The Rhododendron Species Botanical Garden at the Weyerhaeuser Corporate Headquarters, in Federal Way, Washington. Satellite fern gardens are at the Birmingham Botanical Gardens, Birmingham, Alabama, California State University at Sacramento, California, Coastal Maine Botanical Garden, Boothbay , Maine. Dallas Arboretum, Dallas, Texas, Denver Botanic Gardens, Denver, Colorado, Georgeson Botanical Garden, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, Alaska, Harry R Leu Garden, Orlando, Florida, Inniswood Metro Gardens, Columbus, Ohio, New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York, and Strybing Arboretum, San Francisco, California. The fern display gardens are at Bainbridge Island Library. Bainbridge Island, WA, Bellevue Botanical Garden, Bellevue, WA, Lakewold, Tacoma, Washington, Lotusland, Santa Barbara, California, Les Jardins de Metis, Quebec, Canada, Rotary Gardens, Janesville, Wl, and Whitehall Historic Home and Garden, Louisville, KY. Hardy Fern Foundation members participate in a spore exchange, receive a quarterly newsletter and have first access to ferns as they are ready for distribution. Cover design by Willanna Bradner HARDY FERN FOUNDATION QUARTERLY THE HARDY FERN FOUNDATION QUARTERLY Volume 20 No. 3 Editor- Sue Olsen ISSN 154-5517 T7 a -On I »§ jg 3$.as a 1 & bJLsiSLslSi ^ ~~}.J j'.fc President’s Message Patrick Kennar Osmundastrum reinstated, for Osmunda cinnamomea, Cinnamon fern Alan R.