Stillbirth Risk During the 1918 Influenza Pandemic in Arizona

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DECEMBER 1918 Published by the West Virginia Collegiate Institute Institute, W

THE INSTITUTE MONTHLY FOR DECEMBER 1918 Published By The West Virginia Collegiate Institute Institute, W. Va. The Institute Monthly The Institute Monthly Entered as second-class matter, January 29,1914, at the post-Office at Institute, West Vir- Entered 81 second-class matter, January 29, 1914, at the post-Office at Institute, West Vir- ginia, under the act of Marh 3, 1879. ginia, under the act of March 3, 1879. Vol. 11 DECEMBER 1918 No.2 Vol. 11 DECEMBER 1918 Number 2 II Devoted to the Interests of The West Virginia Collegiate Institute ~====Tw==en=t=Y-=fi=ve==c=en=t=s=th=e=s=c=ho=l=as=ti=c=Y=e=ar=.==========F=i=ve==ce=n=ts==p=er=c=o=p=Y===D EDITORIALS CONTENTS r.=======;l HE eleventh hour of orgy of murder and destruction, PAGE II the eleven th day of it must dawn upon us that some the eleventh month of our well established ideals must Editorials 3 T of 1918, should ever be reconstructed. Perhaps, a be rem em b ere d. greater opportunity, to begin such "Golden Thoughts" 4 For the first time in reconstruction, can arise in no 4 A letter from Mr. Shawkey L-- --' four years, it more fitting places than our A letter from Mr. Hartshorn 5 marked a general cessation of that schools. carnival of death which, involving We are convinced by the Hun's A letter from Mr. Marsh 5 the whole world, has ravaged the acknowledgment of defeat, that A letter from the Commissoner of Agriculture 5 continent of Europe. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

American Armies and Battlefields in Europe

Chapter v1 THE AMERICAN BATTLEFIELDS NORTH OF PARIS chapter gives brief accounts of areas and to all of the American ceme- all American fighting whi ch oc- teries and monuments. This route is Thiscurred on the battle front north of recommended for those who desire to Paris and complete information concern- make an extended automobile tour in the ing the American military cemeteries and region. Starting from Paris, it can be monuments in that general region. The completely covered in four days, allowing military operations which are treated are plenty of time to stop on the way. those of the American lst, 27th, 30th, The accounts of the different operations 33d, 37th, 80th and 91st Divisions and and the descriptions of the American the 6th and 11 th Engineer Regiments. cemeteries and monuments are given in Because of the great distances apart of the order they are reached when following So uthern Encr ance to cb e St. Quentin Can al Tunnel, Near Bellicourc, October 1, 1918 the areas where this fighting occurred no the suggested route. For tbis reason they itinerary is given. Every operation is do not appear in chronological order. described, however, by a brief account Many American units otber tban those illustrated by a sketch. The account and mentioned in this chapter, sucb as avia- sketch together give sufficient information tion, tank, medical, engineer and infantry, to enable the tourist to plan a trip through served behind this part of the front. Their any particular American combat area. services have not been recorded, however, The general map on the next page as the space limitations of tbis chapter indicates a route wbich takes the tourist required that it be limited to those Amer- either int o or cl ose to all of tbese combat ican organizations which actually engaged (371) 372 THE AMERICAN B ATTLEFIELD S NO R TH O F PARIS Suggested Tour of American Battlefields North of Paris __ Miles Ghent ( î 37th and 91st Divisions, Ypres-Lys '"offensive, October 30-November 11, 1918 \ ( N \ 1 80th Division, Somme 1918 Albert 33d Division. -

Conflict of Revolutionary Authority: Provisional Government Vs. Berlin Soviet, November-December 1918 1

HENRY EGON FRIEDLANDER CONFLICT OF REVOLUTIONARY AUTHORITY: PROVISIONAL GOVERNMENT VS. BERLIN SOVIET, NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 1918 1 The Russian revolutions of 1905 and 1917 saw the first appearance of workers' and soldiers' councils, called Soviets. In 1917 the Executive Committee of the Petrograd Soviet, acting for all the Russian Soviets, became the chief competitor of Kerensky's Provisional Government. The Bolsheviks, employing the slogan "All Powers to the Soviets", used the Petrograd Soviet in their drive for power. In the October Revolution the Soviets, dominated by the Bolsheviks, replaced the Provisional Government as the government of Russia. In the German Revolution of November 1918 workers' and soldiers' councils, called Rate, were organized in imitation of the Russian Soviets.2 The German Revolution created, as had the Russian 1 This article is based on a paper presented at the European history section of the meeting of the (American) Southern Historical Association in Tulsa, Oklahoma, November i960. 2 "Ratewahlen," in Die Freiheit: Berliner Organ der Unabhangigen Sozialdemokratischen Partei Deutschlands, November 16, 1918 (evening); A. Stein, "Rateorganisation und Revolution," in ibid., November 17, 1918 (morning); Vorwarts: Berliner Volksblatt, Zentralorgan der Sozialdemokratischen Partei Deutschlands, November 9, 1918 (ist, 3rd, and 5th Extraausgabe); November 10, 1918 (8th Extraausgabe); Leipziger Volkszeitung: Organ fiir die Interessen des gesamten werktatigen Volkes, November 5-9, 1918; "Wahl der Arbeiterrate," in Rote Fahne (Ehemaliger Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger), November 10, 1918. For further information on the German Revolution, the socialist parties, and the formation of the workers' and soldiers' councils, see Emil Barth, Aus der Werkstatt der deutschen Revolution (Berlin, 1919), pp. -

The Portuguese Expeditionary Corps in World War I: from Inception To

THE PORTUGUESE EXPEDITIONARY CORPS IN WORLD WAR I: FROM INCEPTION TO COMBAT DESTRUCTION, 1914-1918 Jesse Pyles, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2012 APPROVED: Geoffrey Wawro, Major Professor Robert Citino, Committee Member Walter Roberts, Committee Member Richard McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Pyles, Jesse, The Portuguese Expeditionary Corps in World War I: From Inception to Destruction, 1914-1918. Master of Arts (History), May 2012, 130 pp., references, 86. The Portuguese Expeditionary Force fought in the trenches of northern France from April 1917 to April 1918. On 9 April 1918 the sledgehammer blow of Operation Georgette fell upon the exhausted Portuguese troops. British accounts of the Portuguese Corps’ participation in combat on the Western Front are terse. Many are dismissive. In fact, Portuguese units experienced heavy combat and successfully held their ground against all attacks. Regarding Georgette, the standard British narrative holds that most of the Portuguese soldiers threw their weapons aside and ran. The account is incontrovertibly false. Most of the Portuguese combat troops held their ground against the German assault. This thesis details the history of the Portuguese Expeditionary Force. Copyright 2012 by Jesse Pyles ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The love of my life, my wife Izabella, encouraged me to pursue graduate education in history. This thesis would not have been possible without her support. Professor Geoffrey Wawro directed my thesis. He provided helpful feedback regarding content and structure. Professor Robert Citino offered equal measures of instruction and encouragement. -

1918 in Bethel & Danbury Connecticut

The “Spanish” Influenza Pandemic in Bethel & Danbury Connecticut As Reported in the Danbury News & Danbury Evening News “A JOURNAL OF TO-DAY – THE RECORD OF A YANKEE TOWN” Selected Headlines & Accounts of the Second Wave September 12th 1918 through January 29 th 1919 Eric S. Starbuck, DrPH, MPH 1 April 8, 2007 Draft Selected Headlines, Reports, and Findings • September 28: Danbury Hospital Superintendent busy seeking nurses in Danbury to send to Camp Devens, Massachusetts, in response to their urgent appeal. • October 5: Connecticut state-wide appeal to “use every means to keep nurses in this state.” • October 4: Danbury “Schools Closed As Precaution.” • October 5: Danbury theatres closed. • October 5: “Directly conflicting opinions in regard to the advisability of closing schools and theatres and other places of public gatherings ….. by federal and state health officials.” • October 10: Danbury Fair closed and public dances prohibited. • October 17: Bethel call for volunteers to help care for the ill. • October 21: “Epidemic Hits Coal Supply” - many coal miners ill. • October 25: “Physicians and nurses are still working almost to the limit of their endurance and the hospitals are practically filled with patients. All effort is being made to divert influenza and pneumonia patients from the Danbury hospital to the emergency hospital, so far as possible. It was stated this afternoon, however, that the emergency hospital, opened in the Children’s Home on Town Hill avenue two days ago, will probably be filled by tonight. ....... Bad as the situation is here, it is good compared with that in several other places in Connecticut.” • November 8: Bethel cabinet maker making caskets because “it is difficult to secure caskets of any kind.” • Although these accounts reflect a decent understanding of the modes of person-to-person transmission, and most non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) now under consideration 89 years later, were tried in Connecticut in 1918, there were substantial differences in which NPIs individual communities decided to implement. -

The Impact of the 1918-1919 Influenza Epidemic on Virginia Stephanie Forrest Barker

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 2002 The impact of the 1918-1919 influenza epidemic on Virginia Stephanie Forrest Barker Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Barker, Stephanie Forrest, "The impact of the 1918-1919 influenza epidemic on Virginia" (2002). Master's Theses. Paper 1169. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Impact of the 1918-1919 Influenza Epidemic on Virginia By Stephanie Forrest Barker Master of Arts in History, University of Richmond, 2002 R. Barry Westin, Thesis Director In the fall of 1918 an unparalleled influenza pandemic spread throughout the world. More than a quarter of Americans became ill, and at least 600,000 died. For many Virginians, this was a time of acute crisis that only could be compared to the days of the Civil War. This thesis describes Spanish influenza's impact on Virginia, primarily focusing on the cities of Newport News, Richmond, and Roanoke. It details influenza's emergence in Virginia and explores how state and city officials dealt with this unprecedented epidemic. This study examines how the epidemic disrupted daily routines of life and overwhelmed the state's medical community. This thesis briefly discusses the effect that the segregation of races had on the spread of influenza and the role that women played in battling the epidemic. -

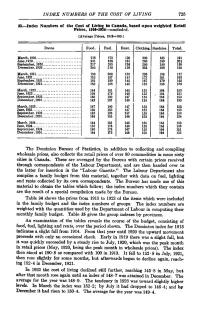

INDEX NUMBERS of the COST of LIVING 725 33.—Index Numbers of the Cost of Living in Canada, Based Upon Weighted Retail Prices

INDEX NUMBERS OF THE COST OF LIVING 725 33.—Index Numbers of the Cost of Living in Canada, based upon weighted Retail Prices, 1910-1934—concluded. (Average Prices, 1913=100.) Dates. Food. Fuel. Rent. Clothing. Sundries. Total. March, 1920 218 173 120 260 185 191 June,1920 231 186 133 260 190 201 September, 1920 217 285 136 260 190 199 December, 1920. 202 218 139 235 190 192 March, 1921 180 208 139 195 188 177 June,1921 152 197 143 173 181 163 September, 1921 161 189 145 167 170 162 December, 1921. 150 186 145 158 166 156 March, 1922 144 181 145 155 164 153 June, 1922 139 179 146 155 . 164 151 September, 1922. 140 190 147 155 164 153 December, 1922. 142 187 146 155 164 153 March, 1923 147 190 147 155 164 155 June,1923 139 182 147 155 164 152 September, 1923. 142 183 147 155 164 153 December, 1923. 146 185 146 155 164 154 March, 1924 144 181 146 155 164 153 June,1924 133 176 146 155 164 149 September, 1924. 140 176 147 155 164 151 December, 1924. 144 175 146 155 164 152 The Dominion Bureau of Statistics, in addition to collecting and compiling wholesale prices, also collects the retail prices of over 80 commodities in some sixty cities in Canada. These are averaged by the Bureau with certain prices received through correspondents of the Labour Department, and are then handed over to the latter for insertion in the "Labour Gazette." The Labour Department also compiles a family budget from this material, together with data on fuel, lighting and rents collected by its own correspondents. -

“Pandemic 1918” Study Guide Questions

“Pandemic 1918” Study Guide Questions “Pandemic 1918!” is an article about the experiences of King County residents during the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919. The virus, nicknamed the Spanish Flu, arrived just as the First World War was ending. It is thought to have infected over 500 million people worldwide. This activity is designed for readers in 7th grade and above. Questions can be used for discussion or as writing prompts. You can find the original article from December 2014 on Renton History Museum’s Newsletters Page. 1. Today’s scientists and historians are not sure where the Spanish Flu originated, but it is unlikely that it actually began in Spain. Why was the epidemic called the Spanish Flu? 2. How did health officials in the state of Washington prepare for the arrival of the Spanish Flu? 3. Jessie Tulloch observed firsthand how Seattle adapted to the flu. How did everyday life in Seattle change? 4. On November 11, 1918, the Allied Powers and Germany signed a treaty that officially brought World War I to a close. This day was called Armistice Day, and in modern times it is celebrated as Veteran’s Day in the United States. Why was the first Armistice Day a concern for public health officials? 1 5. According to health officials at the time, the best place for treating the Spanish Flu was at home. Patients were treated in their homes with the aid of family members and traveling nurses and doctors. However, some of the infected individuals had to go to Renton Hospital for treatment. -

Epidemic and Public Health : Influenza in Vancouver, 1918-1919

Epidemic and Public Health : Influenza in Vancouver, 1918-1919 MARGARET W. ANDREWS* TABLE 1 INFLUENZA DEATHS FROM THE BEGINNING OF THE EPIDEMIC TO THE END OF JANUARY 1919 Death Rate per City Deaths 1,000 of population per annum Spokane 428 8.3 Seattle 1,328 11.1 Chicago 12,400 12.4 St. Louis 3,207 13.4 Portland 1,363 13.5 Toronto 2,284 14.3 New York City 27,362 14.4 Newark 2,348 15.8 Winnipeg 1,021 16.7 Los Angeles 2,969 17.0 Buffalo 2,742 18.8 Boston 5,771 19.1 Washington 2,892 20.8 Pittsburgh 4,972 22.9 San Francisco 3,616 23.1 Vancouver 795 23.3 Baltimore 4,358 23.6 Philadelphia 14,198 24.7 SOURCES: Calculations were based on figures from: Crosby, op. cit., pp. 60-61. Ontario, Thirty-Eighth Annual Report of the Provincial Board of Health of Ontario, Canada for the Year 1919 (Toronto: Printer to the King, 1920), p. 236. City of Winnipeg, op. cit., p. 10. The Vancouver Daily Province, 17 February 1919, p. 7. City of Vancouver, Annual Report for Year Ending December 31, 1918 (n.p., n.n., n.d.), p. 73. *The author wishes to acknowledge the research assistance provided by a Canada Council Doctoral Fellowship. BG STUDIES, no. 34, Summer 1977 22 BG STUDIES FIGURE 1 DEATHS BY AGE GROUP — VANCOUVER 1917 300" V "° 200 0 u inn -g £ 1 3 agG e groupn - s 0-9 10-19 20-29 30-39 40-49 50-59 60-69 70-79 80+ 1 1918 400 ( Shaded : deaths due to influenza) age groups I 0-9 20-29 I 30-39 I 40-49 I 50-59 ( 60-69 I 70-79 I 80 + 1919 age groups! 0-9 20-29 I 30-39 I 40-49 I 50-59 I 60-69 I 70-79 I 80 + 1920 ?nn •5 d <v w ^IfU •o u inn m nu 1 age groups 0-9 10-19 20-29 30-39 40-49 50-59 60-69 70-79 80+ 1 SOURCES: City of Vancouver, Dept. -

The Paris Peace Conference (1919-1920) and Its Aftermath

The Paris Peace Conference (1919-1920) and Its Aftermath The Paris Peace Conference (1919-1920) and Its Aftermath: Settlements, Problems and Perceptions Edited by Sorin Arhire and Tudor Roşu The Paris Peace Conference (1919-1920) and Its Aftermath: Settlements, Problems and Perceptions Edited by Sorin Arhire and Tudor Roşu This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Sorin Arhire, Tudor Roşu and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-4224-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-4224-2 Cover Image: Sturdza Palace (photo taken around 1930) which was the headquarters of the Romanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 1919-1920. Source: Diplomatic Archives of Romanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Bucharest. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Sorin ARHIRE and Tudor ROȘU Chapter One ............................................................................................... 3 The Romanian Americans and the Paris Peace Conference: The Trianon Treaty (4 June 1920) Constantin I. STAN and Mădălina OPREA Chapter -

WORLD WAR ONE: the FEW THAT FED the MANY British Farmers and Growers Played a Significant Role in the War Effort During 1914-1918 to Produce Food for the Nation

NATIONAL FARMERS' UNION WORLD WAR ONE: THE FEW THAT FED THE MANY BRITISH FARMERS AND GROWERS PLAYED A SIGNIFICANT ROLE IN THE WAR EFFORT DURING 1914-1918 TO PRODUCE FOOD FOR THE NATION. THIS REPORT FOCUSES ON HOW THE EVENTS OF THE GREAT WAR CHANGED THE FACE OF BRITISH FARMING AND CHANGED THE WAY FARMERS AND GROWERS PRODUCED FOOD. CONTENTS Britannia ruled the imports In the lead up to World War One the population of Great Britain was 45 million with 1.5 million employed fter the agricultural depression of the 1870s, British The question of domestic food production was raised in a in agriculture. As hundreds of thousands of male farm agriculture was largely neglected by government. report in 1905 from the Royal Commission on the Supply of workers left the fields for the front line, those left behind The development of refrigeration and the Industrial Food and Raw Materials in Time of War. It recommended were expected to produce the food for the nation. ARevolution, that brought steam engines and railways that “it may be prudent to take some minor practical into force, impacted heavily on British farmers. Countries steps to secure food supplies for Britain”. The Government were suddenly able to transport produce across huge focused on the carrying capacity of the merchant fleet and 2-3 Pre-War Britain distances to the ports. Meat, eggs, grains and other goods the Royal Navy to keep the shipping lanes open and did not How did Britain feed the nation before World were transported on ships from Australia, South Africa and heed these early warnings.