Comparison of Solo Music for the Western Lute and Chinese Pipa By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix D Chinese Personal Names and Their Japanese Equivalents

-1155 Appendix D Chinese Personal Names and Their Japanese Equivalents Note: Chinese names are romanized according to the traditional Wade-Giles system. The pinyin romanization appears in parentheses. Chinese Names Japanese Names An Ch’ing-hsü (An Qingxu) An Keisho An Lu-shan (An Lushan) An Rokuzan Chang-an (Zhangan) Shoan Chang Chieh (Zhang Jie) Cho Kai Chang Liang (Zhang Liang) Cho Ryo Chang Wen-chien (Zhang Wenjian) Cho Bunken Chao (Zhao), King Sho-o Chao Kao (Zhao Gao) Cho Ko Ch’en Chen (Chen Zhen) Chin Shin Ch’eng (Cheng), King Sei-o Cheng Hsüan (Zheng Xuan) Tei Gen Ch’eng-kuan (Chengguan) Chokan Chia-hsiang ( Jiaxiang) Kajo Chia-shang ( Jiashang) Kasho Chi-cha ( Jizha) Kisatsu Chieh ( Jie), King Ketsu-o Chieh Tzu-sui ( Jie Zisui) Kai Shisui Chien-chen ( Jianzhen) Ganjin Chih-chou (Zhizhou) Chishu Chih-i (Zhiyi) Chigi z Chih Po (Zhi Bo) Chi Haku Chih-tsang (Zhizang) Chizo Chih-tu (Zhidu) Chido Chih-yen (Zhiyan) Chigon Chih-yüan (Zhiyuan) Shion Ch’i Li-chi (Qi Liji) Ki Riki Ching-hsi ( Jingxi) Keikei Ching K’o ( Jing Ko) Kei Ka Ch’ing-liang (Qingliang) Shoryo Ching-shuang ( Jingshuang) Kyoso Chin-kang-chih ( Jingangzhi) Kongochi 1155 -1156 APPENDIX D Ch’in-tsung (Qinzong), Emperor Kinso-tei Chi-tsang ( Jizang) Kichizo Chou (Zhou), King Chu-o Chuang (Zhuang), King So-o Chuang Tzu (Zhuang Zi) Soshi Chu Fa-lan (Zhu Falan) Jiku Horan Ch’ung-hua (Chonghua) Choka Ch’u Shan-hsin (Chu Shanxin) Cho Zenshin q Chu Tao-sheng (Zhu Daosheng) Jiku Dosho Fa-ch’üan (Faquan) Hassen Fan K’uai (Fan Kuai) Han Kai y Fan Yü-ch’i (Fan Yuqi) Han Yoki Fa-pao -

AGARIE, HIDEO, Part-Time Lecturer, University of Nagoya for Foreign Studies, JAPAN, Ahideo1969@Yahoo

HIGA, ETSUKO, Director, Ginowan City Museum, OKINAWA Uzagaku: Chinese music performed in the Ryukyuan Court Panel: Past and Future of Okinawa Music and Art According to Chuzan Seikan, the first official history of Ryukyuan (Chuzan) Kingdom compiled by the royal government in 1650, ‘the Emperor of the Ming (China) sent the members of 36 (i.e. a large number of) families from the district of Fujian province to Ryukyu in 1392, and it was from this time that the rites and music of China began to be practiced also in the Ryukyuan court.’ It is not known precisely that the music was what ‘the rite and music’ referred to at that time, but assuming that the music was similar to that of the Uzagaku and Rujigaku genres handed down within Okinawa until 1879. Uzagaku was generally performed indoors, while Rujigaku was a type of outdoor processional music featuring instruments such as the reed pipe known as sona, the rappa trumpet, and drums. Uzagaku instruments included about 18 different instruments such as pipa, yueqin, yangqin, huqin, sanhsien, erhsien, sona, drum, and gongs. In my recent research on the theme of Uzagaku, the similar ensembles are found in the mainland Japan (‘Ming-Qing’ Music), Taiwan, and Vietnam. Although the indigenous root of Uzagaku is not yet known, it should be noticed that Uzagaku is a genre which has a close association with the music culture of its neighboring countries of Asia, where had been politically and socially related with the Great China from the 14th to19th century. . -

Stability and Change in Rhythmic Patterning Across a Composer's

Stability and Change in Rhythmic Patterning Across a Composer’s Lifetime: A Study of Four Famous Composers Using the nPVI Equation Joseph R. Daniele & Aniruddh D. Patel Figures 2, 3, and 4 of are displayed within this paper in grayscale. See print color plate for color versions of these figures. For direct embedding of the color figures, refer to the PDF online at http://mp.ucpress.edu/ 256 Joseph R. Daniele & Aniruddh D. Patel STABILITY AND CHANGE IN RHYTHMIC PATTERNING ACROSS A COMPOSER’S LIFETIME:ASTUDY OF FOUR FAMOUS COMPOSERS USING THE NPVI EQUATION JOSEPH R. DANIELE of German and Austrian instrumental classical music University of California, Berkeley between *1600 and 1950. Analyzing 3,195 themes from 21 composers, we found that the average degree ANIRUDDH D. PATEL of durational contrast between notes in musical themes Tufts University (as measured by the normalized pairwise variability index, or nPVI) increased steadily over historical time, HISTORICAL TRENDS IN THE RHYTHM OF WESTERN a trend not seen in Italian classical music during this European instrumental classical music between *1650 same time period. This finding proved relevant to ideas and 1950 have recently been studied using the nPVI in historical musicology regarding the changing influ- equation. This equation measures the average degree ence of Italian music on Austro-German classical music of durational contrast between adjacent events in (see Daniele & Patel, 2013, for details). Our findings a sequence (such as notes in a musical theme). These were based on assigning each composer a single nPVI historical studies (e.g., Daniele & Patel, 2013, Hansen value, representing the mean nPVI of his themes from A et al., in press) have relied on assigning each composer’s Dictionary of Musical Themes (Barlow & Morgenstern, music a mean nPVI value in order to search for broad 1983). -

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

December 9–11, 2016

December 9–11, 2016 2016-2017 Season Sponsor Jeanne Lamon Hall, Trinity-St. Paul’s Centre, 427 Bloor St. West With sincere appreciation and gratitude salutes Al and Jane Forest for their leadership and generous support of this production Be a part of our next CD Recording! The Consort will be heading into the studio to record The Italian Queen of France For your generous support, you will receive the following benefits: Amount You will receive $10 – $124 advance access to purchase the new CD when it is released in the Fall of 2017 $125 – $499 a copy of the new CD $500 or more two copies of the new CD All project donors will receive a tax receipt and will be listed in the house programs for our 2017-18 season Join us in the gymnasium to offer your support today! Magi videntes stellam Chant for the Feast of the Epiphany Nova stella apparita Florence Laudario, ca 1325 Salutiam divotamente Cortona Laudario, ca 1260 Ave regina caelorum Walter Frye (d. 1474) Gabriel fram hevene-King England, late mid-14th century Estampie Gabriel fram hevene-King arr. Toronto Consort Veni veni Emanuel France, ca 1300 O frondens virga Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179) Nicolaus pontifex Paris, ca 1250 Nicolai sollempnia Das Glogauer Liederbuch, ca 1480 Wynter Tours, 14th century Deh tristo mi topinello northern Italy, ca 1400 Farwel Advent Selden MS, England, ca 1450 INTERMISSION Please join us for refreshments and the CD Boutique in the Gymnasium. Hodie aperuit nobis Hildegard von Bingen Nowel! Owt of your slepe aryse and wake Selden MS In dulci jubilo Liederbuch -

002170196E1c16a28b910f.Pdf

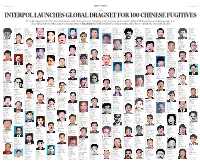

6 THURSDAY, APRIL 23, 2015 DOCUMENT CHINA DAILY 7 JUSTICE INTERPOL LAUNCHES GLOBAL DRAGNET FOR 100 CHINESE FUGITIVES It’s called Operation Sky Net. Amid the nation’s intensifying antigraft campaign, arrest warrants were issued by Interpol China for former State employees and others suspected of a wide range of corrupt practices. China Daily was authorized by the Chinese justice authorities to publish the information below. Language spoken: Liu Xu Charges: Place of birth: Anhui property and goods Language spoken: Zeng Ziheng He Jian Qiu Gengmin Wang Qingwei Wang Linjuan Chinese, English Sex: Male Embezzlement Language spoken: of another party by Chinese Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Female Charges: Date of birth: Chinese, English fraud Charges: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Accepting bribes 07/02/1984 Charges: Embezzlement Embezzlement 15/07/1971 14/11/1965 15/05/1962 03/01/1972 17/07/1980 Place of birth: Beijing Place of birth: Henan Language spoken: Place of birth: Place of birth: Place of birth: Language spoken: Language spoken: Chinese Zhejiang Jinan, Shandong Jilin Chinese, English Chinese Charges: Graft Language spoken: Language spoken: Language spoken: Charges: Corruption Charges: Chinese Chinese, English Chinese Embezzlement Charges: Contract Charges: Commits Charges: fraud, and flight of fraud by means of a Misappropriation of Yang Xiuzhu 25/11/1945 Place of birth: Chinese Zhang Liping capital contribution Chu Shilin letter of credit Dai Xuemin public funds Sex: Female -

Early Fifteenth Century

CONTENTS CHAPTER I ORIENTAL AND GREEK MUSIC Section Item Number Page Number ORIENTAL MUSIC Ι-6 ... 3 Chinese; Japanese; Siamese; Hindu; Arabian; Jewish GREEK MUSIC 7-8 .... 9 Greek; Byzantine CHAPTER II EARLY MEDIEVAL MUSIC (400-1300) LITURGICAL MONOPHONY 9-16 .... 10 Ambrosian Hymns; Ambrosian Chant; Gregorian Chant; Sequences RELIGIOUS AND SECULAR MONOPHONY 17-24 .... 14 Latin Lyrics; Troubadours; Trouvères; Minnesingers; Laude; Can- tigas; English Songs; Mastersingers EARLY POLYPHONY 25-29 .... 21 Parallel Organum; Free Organum; Melismatic Organum; Benedica- mus Domino: Plainsong, Organa, Clausulae, Motets; Organum THIRTEENTH-CENTURY POLYPHONY . 30-39 .... 30 Clausulae; Organum; Motets; Petrus de Cruce; Adam de la Halle; Trope; Conductus THIRTEENTH-CENTURY DANCES 40-41 .... 42 CHAPTER III LATE MEDIEVAL MUSIC (1300-1400) ENGLISH 42 .... 44 Sumer Is Icumen In FRENCH 43-48,56 . 45,60 Roman de Fauvel; Guillaume de Machaut; Jacopin Selesses; Baude Cordier; Guillaume Legrant ITALIAN 49-55,59 · • · 52.63 Jacopo da Bologna; Giovanni da Florentia; Ghirardello da Firenze; Francesco Landini; Johannes Ciconia; Dances χ Section Item Number Page Number ENGLISH 57-58 .... 61 School o£ Worcester; Organ Estampie GERMAN 60 .... 64 Oswald von Wolkenstein CHAPTER IV EARLY FIFTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH 61-64 .... 65 John Dunstable; Lionel Power; Damett FRENCH 65-72 .... 70 Guillaume Dufay; Gilles Binchois; Arnold de Lantins; Hugo de Lantins CHAPTER V LATE FIFTEENTH CENTURY FLEMISH 73-78 .... 76 Johannes Ockeghem; Jacob Obrecht FRENCH 79 .... 83 Loyset Compère GERMAN 80-84 . ... 84 Heinrich Finck; Conrad Paumann; Glogauer Liederbuch; Adam Ile- borgh; Buxheim Organ Book; Leonhard Kleber; Hans Kotter ENGLISH 85-86 .... 89 Song; Robert Cornysh; Cooper CHAPTER VI EARLY SIXTEENTH CENTURY VOCAL COMPOSITIONS 87,89-98 ... -

MP3502 04 Temperley 193..199

Rhythmic Variability in European Vocal Music 193 RHYTHMIC VARIABILITY IN EUROPEAN VOCAL MUSIC DAVID TEMPERLEY to have higher variability in syllable length than French Eastman School of Music of the University of Rochester (Grabe & Low, 2002). Several subsequent studies have further explored cross-cultural correlations between RHYTHMIC VARIABILITY IN THE VOCAL MUSIC OF music and language using nPVI. Huron and Ollen four European nations was examined, using the nPVI (2003) repeated Patel and Daniele’s procedure with measure (normalized pairwise variability index). It was a larger sample of instrumental melodies, and again predicted that English and German songs would show found English melodies to have higher nPVI than higher nPVI than French and Italian ones, mirroring French; they also found that German instrumental mel- the differences between these nations in speech rhythm, odies had relatively low nPVI, which is notable since the and in accord with previous studies of instrumental speech nPVI of German is relatively high. Daniele and music. Surprisingly, there was no evidence of this pat- Patel (2013) suggest that this may be due to the influ- tern, and some evidence of the opposite pattern: nPVI ence of Italian music on German composers (Italian is higher in French and Italian vocal music than in speech, like French, has fairly low nPVI); they show that English and German vocal music. This casts doubt on the nPVI of German instrumental music increases in the theory that the differences in instrumental rhythm the 19th century, as Italian influence wanes. This line between these nations are due to differences in speech of reasoning is pursued by Hansen, Sadakata, and Pearce rhythm. -

Continuing Crackdown in Inner Mongolia

CONTINUING CRACKDOWN IN INNER MONGOLIA Human Rights Watch/Asia (formerly Asia Watch) CONTINUING CRACKDOWN IN INNER MONGOLIA Human Rights Watch/Asia (formerly Asia Watch) Human Rights Watch New York $$$ Washington $$$ Los Angeles $$$ London Copyright 8 March 1992 by Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 1-56432-059-6 Human Rights Watch/Asia (formerly Asia Watch) Human Rights Watch/Asia was established in 1985 to monitor and promote the observance of internationally recognized human rights in Asia. Sidney Jones is the executive director; Mike Jendrzejczyk is the Washington director; Robin Munro is the Hong Kong director; Therese Caouette, Patricia Gossman and Jeannine Guthrie are research associates; Cathy Yai-Wen Lee and Grace Oboma-Layat are associates; Mickey Spiegel is a research consultant. Jack Greenberg is the chair of the advisory committee and Orville Schell is vice chair. HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH Human Rights Watch conducts regular, systematic investigations of human rights abuses in some seventy countries around the world. It addresses the human rights practices of governments of all political stripes, of all geopolitical alignments, and of all ethnic and religious persuasions. In internal wars it documents violations by both governments and rebel groups. Human Rights Watch defends freedom of thought and expression, due process and equal protection of the law; it documents and denounces murders, disappearances, torture, arbitrary imprisonment, exile, censorship and other abuses of internationally recognized human rights. Human Rights Watch began in 1978 with the founding of its Helsinki division. Today, it includes five divisions covering Africa, the Americas, Asia, the Middle East, as well as the signatories of the Helsinki accords. -

A Review of the Origin and Evolution of Uygur Musical Instruments

2019 International Conference on Humanities, Cultures, Arts and Design (ICHCAD 2019) A Review of the Origin and Evolution of Uygur Musical Instruments Xiaoling Wang, Xiaoling Wu Changji University Changji, Xinjiang, China Keywords: Uygur Musical Instruments, Origin, Evolution, Research Status Abstract: There Are Three Opinions about the Origin of Uygur Musical Instruments, and Four Opinions Should Be Exact. Due to Transliteration, the Same Musical Instrument Has Multiple Names, Which Makes It More Difficult to Study. So Far, the Origin of Some Musical Instruments is Difficult to Form a Conclusion, Which Needs to Be Further Explored by People with Lofty Ideals. 1. Introduction Uyghur Musical Instruments Have Various Origins and Clear Evolution Stages, But the Process is More Complex. I Think There Are Four Sources of Uygur Musical Instruments. One is the National Instrument, Two Are the Central Plains Instruments, Three Are Western Instruments, Four Are Indigenous Instruments. There Are Three Changes in the Development of Uygur Musical Instruments. Before the 10th Century, the Main Musical Instruments Were Reed Flute, Flute, Flute, Suona, Bronze Horn, Shell, Pottery Flute, Harp, Phoenix Head Harp, Kojixiang Pipa, Wuxian, Ruan Xian, Ruan Pipa, Cymbals, Bangling Bells, Pan, Hand Drum, Iron Drum, Waist Drum, Jiegu, Jilou Drum. At the Beginning of the 10th Century, on the Basis of the Original Instruments, Sattar, Tanbu, Rehwap, Aisi, Etc New Instruments Such as Thar, Zheng and Kalong. after the Middle of the 20th Century, There Were More Than 20 Kinds of Commonly Used Musical Instruments, Including Sattar, Trable, Jewap, Asitar, Kalong, Czech Republic, Utar, Nyi, Sunai, Kanai, Sapai, Balaman, Dapu, Narre, Sabai and Kashtahi (Dui Shi, or Chahchak), Which Can Be Divided into Four Categories: Choral, Membranous, Qiming and Ti Ming. -

The Trecento Lute

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title The Trecento Lute Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1kh2f9kn Author Minamino, Hiroyuki Publication Date 2019 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Trecento Lute1 Hiroyuki Minamino ABSTRACT From the initial stage of its cultivation in Italy in the late thirteenth century, the lute was regarded as a noble instrument among various types of the trecento musical instruments, favored by both the upper-class amateurs and professional court giullari, participated in the ensemble of other bas instruments such as the fiddle or gittern, accompanied the singers, and provided music for the dancers. Indeed, its delicate sound was more suitable in the inner chambers of courts and the quiet gardens of bourgeois villas than in the uproarious battle fields and the busy streets of towns. KEYWORDS Lute, Trecento, Italy, Bas instrument, Giullari any studies on the origin of the lute begin with ancient Mesopota- mian, Egyptian, Greek, or Roman musical instruments that carry a fingerboard (either long or short) over which various numbers M 2 of strings stretch. The Arabic ud, first widely introduced into Europe by the Moors during their conquest of Spain in the eighth century, has been suggest- ed to be the direct ancestor of the lute. If this is the case, not much is known about when, where, and how the European lute evolved from the ud. The presence of Arabs in the Iberian Peninsula and their cultivation of musical instruments during the middle ages suggest that a variety of instruments were made by Arab craftsmen in Spain. -

Pipa Virtuoso Fang Leads WSO Back to Classics

Print Story - canada.com network Page 1 of 2 Saturday » February 16 » 2008 Pipa virtuoso Fang leads WSO back to classics Ted Shaw The Windsor Star Sunday, February 10, 2008 It was back to the classics Saturday for the Windsor Symphony Orchestra, but the spirit of the recent Windsor Canadian Music Festival lingered in a contemporary Chinese work. WCMF unveils new Canadian compositions with often unconventional or experimental instrumentation. While Tan Dun's Concerto for String Orchestra and Pipa is not Canadian, it was performed by Montreal-based pipa virtuoso, Liu Fang, and called upon the string players to beat the tops of their instruments at times and shout Chinese words. It was particularly striking in the context of the rest of the program of works written before the first decade of the 19th century. CREDIT: Scott Webster, The Windsor Star Pipa player Liu Fang performs with the Windsor Chinese-born Tan Dun is the Grammy and Oscar-winning Symphony Orchestra Saturday night. composer of such film soundtracks as Hero and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. His use of traditional Chinese instruments in the context of Western musical idioms has earned him a special place among the new generation of composers living in the United States. His pipa concerto is classically structured and borrows liberally from the concerto tradition, including having a cadenza. But the instrument itself is decidedly exotic in sound. Pear-shaped like a lute but lacking a sound hole, the pipa has a percussive quality and is plucked with plectrums, although there is a considerable amount of chord work and strumming involved, as well.