The Russian Popular Culture of Space Exploration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soviet Steps Toward Permanent Human Presence in Space

SALYUT: Soviet Steps Toward Permanent Human Presence in Space December 1983 NTIS order #PB84-181437 Recommended Citation: SALYUT: Soviet Steps Toward Permanent Human Presence in Space–A Technical Mere- orandum (Washington, D. C.: U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, OTA- TM-STI-14, December 1983). Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 83-600624 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 Foreword As the other major spacefaring nation, the Soviet Union is a subject of interest to the American people and Congress in their deliberations concerning the future of U.S. space activities. In the course of an assessment of Civilian Space Stations, the Office of Technology Assessment (OTA) has undertaken a study of the presence of Soviets in space and their Salyut space stations, in order to provide Congress with an informed view of Soviet capabilities and intentions. The major element in this technical memorandum was a workshop held at OTA in December 1982: it was the first occasion when a significant number of experts in this area of Soviet space activities had met for extended unclassified discussion. As a result of the workshop, OTA prepared this technical memorandum, “Salyut: Soviet Steps Toward Permanent Human Presence in Space. ” It has been reviewed extensively by workshop participants and others familiar with Soviet space activities. Also in December 1982, OTA wrote to the U. S. S. R.’s Ambassador to the United States Anatoliy Dobrynin, requesting any information concerning present and future Soviet space activities that the Soviet Union judged could be of value to the OTA assess- ment of civilian space stations. -

Global Exploration Roadmap

The Global Exploration Roadmap January 2018 What is New in The Global Exploration Roadmap? This new edition of the Global Exploration robotic space exploration. Refinements in important role in sustainable human space Roadmap reaffirms the interest of 14 space this edition include: exploration. Initially, it supports human and agencies to expand human presence into the robotic lunar exploration in a manner which Solar System, with the surface of Mars as • A summary of the benefits stemming from creates opportunities for multiple sectors to a common driving goal. It reflects a coordi- space exploration. Numerous benefits will advance key goals. nated international effort to prepare for space come from this exciting endeavour. It is • The recognition of the growing private exploration missions beginning with the Inter- important that mission objectives reflect this sector interest in space exploration. national Space Station (ISS) and continuing priority when planning exploration missions. Interest from the private sector is already to the lunar vicinity, the lunar surface, then • The important role of science and knowl- transforming the future of low Earth orbit, on to Mars. The expanded group of agencies edge gain. Open interaction with the creating new opportunities as space agen- demonstrates the growing interest in space international science community helped cies look to expand human presence into exploration and the importance of coopera- identify specific scientific opportunities the Solar System. Growing capability and tion to realise individual and common goals created by the presence of humans and interest from the private sector indicate and objectives. their infrastructure as they explore the Solar a future for collaboration not only among System. -

Trade Studies Towards an Australian Indigenous Space Launch System

TRADE STUDIES TOWARDS AN AUSTRALIAN INDIGENOUS SPACE LAUNCH SYSTEM A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Engineering by Gordon P. Briggs B.Sc. (Hons), M.Sc. (Astron) School of Engineering and Information Technology, University College, University of New South Wales, Australian Defence Force Academy January 2010 Abstract During the project Apollo moon landings of the mid 1970s the United States of America was the pre-eminent space faring nation followed closely by only the USSR. Since that time many other nations have realised the potential of spaceflight not only for immediate financial gain in areas such as communications and earth observation but also in the strategic areas of scientific discovery, industrial development and national prestige. Australia on the other hand has resolutely refused to participate by instituting its own space program. Successive Australian governments have preferred to obtain any required space hardware or services by purchasing off-the-shelf from foreign suppliers. This policy or attitude is a matter of frustration to those sections of the Australian technical community who believe that the nation should be participating in space technology. In particular the provision of an indigenous launch vehicle that would guarantee the nation independent access to the space frontier. It would therefore appear that any launch vehicle development in Australia will be left to non- government organisations to at least define the requirements for such a vehicle and to initiate development of long-lead items for such a project. It is therefore the aim of this thesis to attempt to define some of the requirements for a nascent Australian indigenous launch vehicle system. -

From the Earth to Outer Space

From the Earth to Outer Space Many years ago, people here on Earth decided that they wanted to go into outer space. This is something people had imagined for a very long time, in books and movies and stories grandparents told to their grandchildren. However, in the 1950s, people decided they really wanted to do it. There was just one problem: how would they get there? One of the earliest movies about flying to the moon was made by Georges Méliès and released in 1902. It was called A Trip to the Moon. In this movie, the moon was made up of a man’s face, covered in cream, and a whole tribe of angry natives lived there. That part was not very realistic. However, the spaceship didn’t seem too far-fetched: it was a small capsule, shaped like a bullet, that the astronauts loaded into a giant cannon and aimed at the moon. This movie was based on a book that came out many years earlier by an author named Jules Verne. One of the fans of the book was a Russian man, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. The book made him think. Could you really shoot people out of a cannon and have them get safely to the moon? He decided you couldn’t, but it got him thinking of other ways you could get people to the moon. He spent his life considering this problem and came up with many solutions. © 2013 ReadWorks®, Inc. All rights reserved. Some of Tsiolkovsky’s solutions gave scientists in America and Russia (where Tsiolkovsky lived) ideas when they began to think about space travel. -

Past, Present, and Future

Rockets: Past, Present, and Future Robert Goddard With his Original Rocket system Delta IV … biggest commercial Rocket system currently in US arsenal Material from Rockets into Space by Frank H. Winter, ISBN 0-674-77660-7 MAE 5540 - Propulsion Systems Earliest Rockets as weapons • Chinese development, Sung dynasty (A.D. 960-1279) – Primarily psychological • William Congreve, England, 1804 – thus “the rockets red glare” during the war of 1812. – 1.5 mile range, very poor accuracy. • V2 in WWII MAE 5540 - Propulsion Systems First Principle of Rocket Flight • “For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.” Isaac Newton, 1687, following Archytas of Tarentum, 360 BC, and Hero of Alexandria, circa 50 AD. • “Rockets move because the flame pushes against the surrounding air.” Edme Mariotte, 1717 • Which one is correct? MAE 5540 - Propulsion Systems Isaac Newton explains how to launch a Satellite MAE 5540 - Propulsion Systems The Reaction-propelled Spaceship of Hermann Ganswindt (1890) • The fuel for his spaceship consisted of heavy steel cartridges with dynamite charges. They were to be fed machine gun style into a reaction chamber where they would fire and be dropped away. • “Shock absorbers protected the travelers” MAE 5540 - Propulsion Systems The Three Amigos of Spaceflight Theory • Konstantin Tsiolkovsky • Hermann Oberth • Robert Goddard • Independent and parallel development of Rocket theory MAE 5540 - Propulsion Systems Three Amigos • Goddard • Oberth • Tsiolkovsky MAE 5540 - Propulsion Systems Konstantin Tsiolkovsky 1857 - 1935 • Deaf Russian School Teacher - fascinated with space flight, started by writing Science Fiction Novels • Discovered that practical space flight depended on liquid fuel rockets in the 1890’s, and developed the fundamental Rocket equation in 1897. -

A Pictorial History of Rockets

he mighty space rockets of today are the result A Pictorial Tof more than 2,000 years of invention, experi- mentation, and discovery. First by observation and inspiration and then by methodical research, the History of foundations for modern rocketry were laid. Rockets Building upon the experience of two millennia, new rockets will expand human presence in space back to the Moon and Mars. These new rockets will be versatile. They will support Earth orbital missions, such as the International Space Station, and off- world missions millions of kilometers from home. Already, travel to the stars is possible. Robotic spacecraft are on their way into interstellar space as you read this. Someday, they will be followed by human explorers. Often lost in the shadows of time, early rocket pioneers “pushed the envelope” by creating rocket- propelled devices for land, sea, air, and space. When the scientific principles governing motion were discovered, rockets graduated from toys and novelties to serious devices for commerce, war, travel, and research. This work led to many of the most amazing discoveries of our time. The vignettes that follow provide a small sampling of stories from the history of rockets. They form a rocket time line that includes critical developments and interesting sidelines. In some cases, one story leads to another, and in others, the stories are inter- esting diversions from the path. They portray the inspirations that ultimately led to us taking our first steps into outer space. NASA’s new Space Launch System (SLS), commercial launch systems, and the rockets that follow owe much of their success to the accomplishments presented here. -

On the Legality of Mars Colonisation

Joshua Fitzmaurice* and Stacey Henderson** ON THE LEGALITY OF MARS COLONISATION ‘Humanity will not remain on the earth forever, but in pursuit of light and space it will at first timidly penetrate beyond the limits of the atmosphere, and then conquer all the space around the sun.’1 ABSTRACT Recent technological advancements made by governmental agencies and private industry have raised hopes for the future of human space flight beyond the Moon. These advancements are increasing the feasibil- ity of endeavours to establish a permanent human habitat on Mars, as a safeguard for our species, for scientific endeavours, and for commercial purposes. This article analyses some of the legal issues associated with Mars colonisation, focusing on the lawfulness of such a venture and the legal status of colonists. I INTRODUCTION ecent technological advancements made by governmental agencies and private industry have raised hopes for the future of human space flight beyond Rthe Moon. The United States’ National Aeronautics and Space Administration (‘NASA’) is developing a new generation of launch and crew systems that will enable * Surveillance of Space Capability Officer, Royal Australian Air Force; MSc (Physics, Space Operations) RMC Canada. Email: [email protected]. The views expressed in this article are personal views and should not be interpreted as an official position. ** Lecturer, Adelaide Law School, The University of Adelaide; PhD (Adel). Email: [email protected]. 1 Letter from Konstantin Tsiolkovsky to Boris Vorobiev, 12 August 1911. See, eg, Rex Hall and David Shayler, The Rocket Men: Vostok & Voskhod: The First Soviet Manned Space-flights (Springer, 2001). -

Pioneers of Spaceflight E S S S O N 9 P L - a 1 S N 2 T E N P

ROCKETROCKET LABLABTM T G w o R C Science A l a s D s L E Pioneers of Spaceflight e s S s o n 9 P l - a 1 S n 2 T E N P (First class session: 20-25 minutes) A Standard G LEARN T I History and Nature of Science 1.Objectives O • Students will be able to identify the pioneers of spaceflight N Standard 13 and their contributions to science and technology. A Understands the scientific • Students will experience what it is like to be a pioneer of L enterprise spaceflight while building and launching an Estes model rocket. S T A Benchmark 1 Materials N Knows that, throughout histo- 1. Generic E2X®, Alpha III® or UP Aerospace™ SpaceLoft ™ D ry, diverse cultures have Rocket Lab Pack™ (12 pack) - 2 or more A developed scientific ideas and 2. Rocket Engine Lab Pack™ (24 pack) - 1 or more R solved human problems 3. Electron Beam® Launch Controller - 1 or more D through technology. 4. Porta-Pad® II Launch Pad - 1 or more 5. Paper, pencil, white or carpenter’s glue or plastic cement, Benchmark 2 scissors, modeling knife, ruler and masking tape for each Understands that individuals student and teams contribute to sci- 6. History of Rockets PowerPoint ence and engineering at dif- ferent levels of complexity. Time Two class sessions Background History of Rockets (Slide 1) Where It All Began (Slide 2) The origins of modern rocketry can be traced back to Greece and China. One of the first devices to utilize the principles of rocket flight was a wooden bird. -

Part 2 Almaz, Salyut, And

Part 2 Almaz/Salyut/Mir largely concerned with assembly in 12, 1964, Chelomei called upon his Part 2 Earth orbit of a vehicle for circumlu- staff to develop a military station for Almaz, Salyut, nar flight, but also described a small two to three cosmonauts, with a station made up of independently design life of 1 to 2 years. They and Mir launched modules. Three cosmo- designed an integrated system: a nauts were to reach the station single-launch space station dubbed aboard a manned transport spacecraft Almaz (“diamond”) and a Transport called Siber (or Sever) (“north”), Logistics Spacecraft (Russian 2.1 Overview shown in figure 2-2. They would acronym TKS) for reaching it (see live in a habitation module and section 3.3). Chelomei’s three-stage Figure 2-1 is a space station family observe Earth from a “science- Proton booster would launch them tree depicting the evolutionary package” module. Korolev’s Vostok both. Almaz was to be equipped relationships described in this rocket (a converted ICBM) was with a crew capsule, radar remote- section. tapped to launch both Siber and the sensing apparatus for imaging the station modules. In 1965, Korolev Earth’s surface, cameras, two reentry 2.1.1 Early Concepts (1903, proposed a 90-ton space station to be capsules for returning data to Earth, 1962) launched by the N-1 rocket. It was and an antiaircraft cannon to defend to have had a docking module with against American attack.5 An ports for four Soyuz spacecraft.2, 3 interdepartmental commission The space station concept is very old approved the system in 1967. -

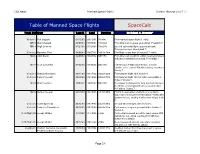

Table of Manned Space Flights Spacecalc

CBS News Manned Space Flights Current through STS-117 Table of Manned Space Flights SpaceCalc Total: 260 Crew Launch Land Duration By Robert A. Braeunig* Vostok 1 Yuri Gagarin 04/12/61 04/12/61 1h:48m First manned space flight (1 orbit). MR 3 Alan Shepard 05/05/61 05/05/61 15m:22s First American in space (suborbital). Freedom 7. MR 4 Virgil Grissom 07/21/61 07/21/61 15m:37s Second suborbital flight; spacecraft sank, Grissom rescued. Liberty Bell 7. Vostok 2 Guerman Titov 08/06/61 08/07/61 1d:01h:18m First flight longer than 24 hours (17 orbits). MA 6 John Glenn 02/20/62 02/20/62 04h:55m First American in orbit (3 orbits); telemetry falsely indicated heatshield unlatched. Friendship 7. MA 7 Scott Carpenter 05/24/62 05/24/62 04h:56m Initiated space flight experiments; manual retrofire error caused 250 mile landing overshoot. Aurora 7. Vostok 3 Andrian Nikolayev 08/11/62 08/15/62 3d:22h:22m First twinned flight, with Vostok 4. Vostok 4 Pavel Popovich 08/12/62 08/15/62 2d:22h:57m First twinned flight. On first orbit came within 3 miles of Vostok 3. MA 8 Walter Schirra 10/03/62 10/03/62 09h:13m Developed techniques for long duration missions (6 orbits); closest splashdown to target to date (4.5 miles). Sigma 7. MA 9 Gordon Cooper 05/15/63 05/16/63 1d:10h:20m First U.S. evaluation of effects of one day in space (22 orbits); performed manual reentry after systems failure, landing 4 miles from target. -

Asteroid Mining with Small Spacecraft and Its Economic Feasibility

Asteroid mining with small spacecraft and its economic feasibility Pablo Callaa,, Dan Friesb, Chris Welcha aInternational Space University, 1 Rue Jean-Dominique Cassini, 67400 Illkirch-Graffenstaden, France bInitiative for Interstellar Studies, Bone Mill, New Street, Charfield, GL12 8ES, United Kingdom Abstract Asteroid mining offers the possibility to revolutionize supply of resources vital for human civilization. Pre- liminary analysis suggests that Near-Earth Asteroids (NEA) contain enough volatile and high value minerals to make the mining process economically feasible. Considering possible applications, specifically the mining of water in space has become a major focus for near-term options. Most proposed projects for asteroid mining involve spacecraft based on traditional designs resulting in large, monolithic and expensive systems. An alternative approach is presented in this paper, basing the asteroid mining process on multiple small spacecraft. To the best knowledge of the authors, only limited analysis of the asteroid mining capability of small spacecraft has been conducted. This paper explores the possibility to perform asteroid mining operations with spacecraft that have a mass under 500 kg and deliver 100 kg of water per trip. The mining process considers water extraction through microwave heating with an efficiency of 2 Wh/g.The proposed, small spacecraft can reach NEAs within a range of ∼ 0:03 AU relative to earth's orbit, offering a delta V of 437 m/s per one-way trip. A high-level systems engineering and economic analysis provides a closed spacecraft design as a baseline and puts the cost of the proposed spacecraft at $ 113.6 million/unit. The results indicate that more than one hundred spacecraft and their successful operation for over five years are required to achieve a financial break-even point. -

Association of Space Explorers 10Th Planetary Congress Moscow/Lake Baikal, Russia 1994

Association of Space Explorers 10th Planetary Congress Moscow/Lake Baikal, Russia 1994 Commemorative Poster Signature Key Loren Acton Viktor Afanasyev Toyohiro Akiyama STS 51F Soyuz TM-11 Soyuz TM-11 Vladimir Aksyonov Sultan bin Salman al-Saud Buzz Aldrin Soyuz 22, Soyuz T-2 STS 51G Gemini 12, Apollo 11 Alexander Alexandrov Anatoli Artsebarsky Oleg Atkov Soyuz T-9, Soyuz TM-3 Soyuz TM-12 Soyuz T-10 Toktar Aubakirov Alexander Balandin Georgi Beregovoi Soyuz TM-13 Soyuz TM-9 Soyuz 3 Anatoli Berezovoi Karol Bobko Roberta Bondar Soyuz T-5 STS 6, STS 51D, STS 51J STS 42 Scott Carpenter John Creighton Vladimir Dzhanibekov Mercury 7 STS 51G, STS 36, STS 48 Soyuz 27, Soyuz 39, Soyuz T-6 Soyuz T-12, Soyuz T-13 John Fabian Mohammed Faris Bertalan Farkas STS 7, STS 41G Soyuz TM-3 Soyuz 36 Anatoli Filipchenko Dirk Frimout Owen Garriott Soyuz 7, Soyuz 16 STS 45 Skylab III, STS 9 Yuri Glazkov Georgi Grechko Alexei Gubarev Soyuz 24 Soyuz 17, Soyuz 26 Soyuz 17, Soyuz 28 Soyuz T-14 Miroslaw Hermaszewski Alexander Ivanchenkov Alexander Kaleri Soyuz 30 Soyuz 29, Soyuz T-6 Soyuz TM-14 Yevgeni Khrunov Pyotr Klimuk Vladimir Kovolyonok Soyuz 5 Soyuz 13, Soyuz 18, Soyuz 30 Soyuz 25, Soyuz 29, Soyuz T-4 Valeri Kubasov Alexei Leonov Byron Lichtenberg Soyuz 6, Apollo-Soyuz Voskhod 2, Apollo-Soyuz STS 9, STS 45 Soyuz 36 Don Lind Jack Lousma Vladimir Lyakhov STS 51B Skylab III, STS 3 Soyuz 32, Soyuz T-9 Soyuz TM-6 Oleg Makarov Gennadi Manakov Jon McBride Soyuz 12, Soyuz 27, Soyuz T-3 Soyuz TM-10, Soyuz TM-16 STS 41G Ulf Merbold Mamoru Mohri Donald Peterson STS 9,