Arizona Anthropologist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elenco Internet Dei Libri11 12 2020

11/12/2020 ELENCO DEI LIBRI DELLA BIBLIOTECA COMUNALE DI VILLANOVA D'ASTI L'ELENCO è un documento in formato PDF in cui ogni riga contiene i dati di un libro disponibile, (salvo giacenza 0 = prestito in corso). I NUOVI ARRIVI (LIBRI NUOVI O ULTIME DONAZIONI) SI TROVANO AD INIZIARE DALLA PRIMA PAGINA Istruzioni per eseguire la ricerca di una parola chiave (cioè un autore, o un titolo, o parole intere parti di esso). Di preferenza evitare parole accentate o apostrofate (Perchè i titoli memorizzati in maiuscolo non le hanno, o possono non averle) Ricerca con ACROBAT READER: fare clic sull'icona della LENTE, (oppure menù MODIFICA -> TROVA). Comparirà una casella in cui scrivere l'occorrenza cercata. Premere AVANTI. Il ritrovamento è mostrato evidenziato in azzurro. Proseguire la ricerca con i Tasti “Avanti” o “Precedente”. Ricerca con un browser internet (come Chrome; Mozilla Firefox; ecc): 1) Fare clic sul tasto con tre lineette a destra della riga di indirizzo del vostro browser, e scegliere TROVA 2) A seconda del browser utilizzato, in un angolo dello schermo si aprirà una casella in cui inserire la parola cercata. 3) Appena si scrive qualcosa, parte automaticamente la ricerca per trovare la prima occorrenza, che sarà evidenziata in colore. 4) Con le freccette poste accanto alla casella, si naviga a tutte le occorrenze successive o precedenti. ProgressivoAnno Codice MatricolaTitolo Sottotitolo 8047 07/12/2020 15:37853.9.CAR27 8047LE IRREGOLARI BUENOS AIRES HORROR TOUR 8046 07/12/2020 15:26 R7.GRD30 8046 CRISTOFORO COLOMBO. VIAGGIATORE SENZA CONFINI 8045 07/12/2020 15:25 R7.GRD29 8045 ENZO FERRARI. -

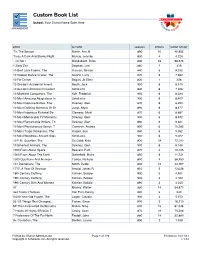

Custom Book List

Custom Book List School: Your District Name Goes Here MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® POINTS WORD COUNT 'Tis The Season Martin, Ann M. 890 10 40,955 'Twas A Dark And Stormy Night Murray, Jennifer 830 4 4,224 ...Or Not? Mandabach, Brian 840 23 98,676 1 Zany Zoo Degman, Lori 860 1 415 10 Best Love Poems, The Hanson, Sharon 840 6 8,332 10 Coolest Dance Crazes, The Swartz, Larry 870 6 7,660 10 For Dinner Bogart, Jo Ellen 820 1 328 10 Greatest Accidental Inventi Booth, Jack 900 6 8,449 10 Greatest American President Scholastic 840 6 7,306 10 Mightiest Conquerors, The Koh, Frederick 900 6 8,034 10 Most Amazing Adaptations In Scholastic 900 6 8,409 10 Most Decisive Battles, The Downey, Glen 870 6 8,293 10 Most Defining Moments Of Th Junyk, Myra 890 6 8,477 10 Most Ingenious Fictional De Clemens, Micki 870 6 8,687 10 Most Memorable TV Moments, Downey, Glen 900 6 8,912 10 Most Remarkable Writers, Th Downey, Glen 860 6 9,321 10 Most Revolutionary Songs, T Cameron, Andrea 890 6 10,282 10 Most Tragic Romances, The Harper, Sue 860 6 9,052 10 Most Wondrous Ancient Sites Scholastic 900 6 9,022 10 P.M. Question, The De Goldi, Kate 830 18 72,103 10 Smartest Animals, The Downey, Glen 900 6 8,148 1000 Facts About Space Beasant, Pam 870 4 10,145 1000 Facts About The Earth Butterfield, Moira 850 6 11,721 1000 Questions And Answers Tames, Richard 890 9 38,950 101 Dalmatians, The Smith, Dodie 830 12 44,767 1777: A Year Of Decision Arnold, James R. -

Masterarbeit

MASTERARBEIT Titel der Masterarbeit „Persephone and Hades Revisited: Modern Retellings of the Myth in Young Adult Literature“ verfasst von Olivia Zajkas, BA angestrebter akademischer Grad Master of Arts (MA) Wien, 2015 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 066 844 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Masterstudium Anglophone Literatures and Cultures Betreut von: Assoz. Prof. Mag. Dr. Susanne Reichl, Privatdoz. “The most common way people give up their power is by thinking they don't have any.” ― Alice Walker “If you’re gonna throw your life away, he’d better have a motorcycle.” ― Lorelai Gilmore Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank my family, my parents and siblings, for their unconditional support over the last few years. Without their help I wouldn’t have been able to achieve this. I would also like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Susanne Reichl, not only for her encouragement and feedback, but also for understanding my passion for this topic. I am also grateful to Dr. Waldemar Zacharasiewicz, who through his kind words strengthened my decision to apply for a Master’s degree in literature (although he most likely forgot about this). Moreover, I have to acknowledge my partner in crime, the Rory to my Lorelai (or vice versa), who has always been there for me on this journey, Steffi. Thank you for everything, where you lead I will follow. All of this would not have been possible without the vital input, encouragement, and support of my friends Peter, Nura, Tami, Connie, Denise, and Sandra. Last but certainly not least, I have to give credit to all the strong female fictional characters I have encountered so far. -

Whore Or Hero? Helen of Troy's Agency And

WHORE OR HERO? HELEN OF TROY’S AGENCY AND RESPONSIBILITY FROM ANTIQUITY TO MODERN YOUNG ADULT FICTION by Alicia Michelle Dixon A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2017 Approved by _____________________________________________ Advisor: Dr. Molly Pasco-Pranger _____________________________________________ Reader: Dr. Brad Cook _____________________________________________ Reader: Dr. Steven Skultety © 2017 Alicia Michelle Dixon ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated, in memoriam, to my father, Daniel Dixon. Daddy, I wouldn’t be here without you. You would have sent me to college on the moon, if that was what I wanted, and because of that, you set me up to shoot for the stars. For the past four years, Ole Miss has been exactly where I belong, and much of my work has culminated in this thesis. I know that, if you were here, you would be so proud to own a copy of it, and you would read every word. It may not be my book, but it’s a start. Your pride in me and your devout belief that I can do absolutely anything that I set my mind to have let me believe that nothing is impossible, and your never ending cheer and kindness are what I aspire to be. Thank you for giving me something to live up to. You are missed every day. Love, Alicia iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, and foremost, the highest level of praise and thanks is deserved by my wonderful advisor, Dr. Molly Pasco-Pranger. -

Thursday (Mar 21) | Track 1 : 12:00 PM- 2:00 PM

Thursday (Mar 21) | Track 1 : 12:00 PM- 2:00 PM 1.29 Teaching the Humanities Online (Workshop) Chair: Susan Ko, Lehman College-CUNY Chair: Richard Schumaker, City University of New York Location: Eastern Shore 1 Pedagogy & Professional 1.31 Lessons from Practice: Creating and Implementing a Successful Learning Community (Workshop) Chair: Terry Novak, Johnson and Wales University Location: Eastern Shore 3 Pedagogy & Professional 1.34 Undergraduate Research Forum and Workshop (Part 1) (Poster Presentations) Chair: Jennifer Mdurvwa, SUNY University at Buffalo Chair: Claire Sommers, Graduate Center, CUNY Location: Bella Vista A (Media Equipped) Pedagogy & Professional "The Role of the Sapphic Gaze in Post-Franco Spanish Lesbian Literature" Leah Headley, Hendrix College "Social Acceptance and Heroism in the Táin " Mikaela Schulz, SUNY University at Buffalo "Né maschile né femminile: come la lingua di genere neutro si accorda con la lingua italiana" Deion Dresser, Georgetown University "Woolf, Joyce, and Desire: Queering the Sexual Epiphany" Kayla Marasia, Washington and Jefferson College "Echoes and Poetry, Mosques and Modernity: A Passage to a Muslim-Indian Consciousness" Suna Cha, Georgetown University "Nick Joaquin’s Tropical Gothic and Why We Need Philippine English Literature" Megan Conley, University of Maryland College Park "Crossing the Linguistic Borderline: A Literary Translation of Shu Ting’s “The Last Elegy”" Yuxin Wen, University of Pennsylvania "World Languages at Rutgers: A Web Multimedia Project" Han Yan, Rutgers University "Interactions Between the Chinese and the Jewish Refugees in Shanghai During World War II" Qingyang Zhou, University of Pennsylvania "“A Vast Sum of Conditions”: Sexual Plot and Erotic Description in George Eliot’s Mill on the Floss" Derek Willie, University of Pennsylvania "Decoding Cultural Representations and Relations in Virtual Reality " Brenna Zanghi, University at Buffalo "D.H. -

Libri Internet 14-9-2020

14/09/2020 NOTE Il prefisso di codice CS indica un libro in sola consultazione La lettera R iniziale del codice, indica un libro per Ragazzi La lettera B iniziale del codice, indica un libro per Bambini Il numero che segue B oppure R indica l'età adeguata ELENCO DEI LIBRI DELLA BIBLIOTECA COMUNALE DI VILLANOVA D'ASTI L'ELENCO è un documento in formato PDF in cui ogni riga contiene i dati di un libro disponibile, (salvo giacenza 0 = prestito in corso). La codifica dei libri è di tipo Dewey semplificata. Il numero iniziale del codice Dewei indica l'argomento del libro I NUOVI ARRIVI (LIBRI NUOVI O ULTIME DONAZIONI) SI TROVANO AD INIZIARE DALLA PRIMA PAGINA come segue: Istruzioni per eseguire la ricerca di una parola chiave (cioè un autore, o un titolo, o parole intere parti di esso). Di preferenza evitare parole accentate o apostrofate (Perchè i titoli memorizzati in maiuscolo non le hanno, o possono non averle) 000 Enciclopedie e opere generali Ricerca con ACROBAT READER: fare clic sull'icona della LENTE, (oppure menù MODIFICA -> TROVA). Comparirà una casella in cui 100 Filosofia e discipline connesse scrivere l'occorrenza cercata. Premere AVANTI. Il ritrovamento è mostrato evidenziato in azzurro. Proseguire la ricerca con i Tasti “Avanti” 200 Religione o “Precedente”. 300 Scienze sociali - Economia, Politica, Diritto ecc. Ricerca con un browser internet (come Chrome; Mozilla Firefox; ecc): 400 Linguaggio 1) Fare clic sul tasto con tre lineette a destra della riga di indirizzo del vostro browser, e scegliere TROVA 500 Scienze naturali e matematica - Fisica, Astronomia, ecc. -

Guide to World Literature

a . # S.. 110CouliT apsent .ED 186 927 4 CS 205 567 11. ,ABTUOR C:arrier, Warren, Olivor, ',Kenneth A., Ed. TITIE t Guide to World Literature,. New Edition. , INSTeITU.TIO I. National Council df Teachers ofEn-glish Urbana,- Ill. 4, REPORT NO' ISBN&O-B141-19492 . Pula DATE ! 80' ; - NOTE /. 2411p.406-'' . AV ni,ABLEFBO Nationralouncil. ol Teacher.b. of English,1111 Kea , . yon Rd.,Urbata,* IL 61801 (S,tock No. 19492, $7.50`,member, .s 4, - $8.50 noa-member) , EDRS PRICE MF01/201b Pluspostage. DESCRIPTORS Cultural Awareness; *English Instruction; Wigher .* Edu6atibn; triticj.sm; *Literature.. Apprciation; NavelS; *Reading .datjrials; Secdidary . Educationi.hort *tories; TeFhing G uiaes; . iLiteratue . , ABST CT 4 I14s guide, a revia.i.o.n af.a 1966 it6rk1by Robert OINe is intended.to.eacourage readijigibeyon'd thetraditioial . 'English:and Aluerican literatUre.texts.by maki4g aaiailaple a. useful re,sourc0 i.an '4r.ea wherefew teachs &aye adequate preparation. The guide contains d'oaparative'reviews ôfthe works Of 136 author's aqdo. seven works without known:auth.ors. Thewor repeesent various genre.s from. Classical to modernftimes andare dra n from 'Asia %and kfrica a§ w0ll as froia Sou'th Ametrica aud.,Europ..Eah reView provides intormat4.0n, about the -authoria short slim hry of thework discussion ofother \Works -by the author.,and a comparison of th-v'iok with*.similar works. Lists Of literature.anthologies an,d of works.of. literary:hist9ry 'and *criticism are iplpended.(tL). 1.. r 5 Jr".. - 4- . i . 11, ********w*********************************************4***************.. ? . * . ReproAuctions supplied..bY EDIS ar9 the best thAt #canbe.niade V .4c , * - from' tte _original docuent., - * . -

Adult Fiction Adult Fiction

Book Based On Book Based On Mythology Mythology Adult Fiction Adult Fiction • The Silence of the Girls by Pat Barker • The Silence of the Girls by Pat Barker • Chasing Embers by James Bennett • Chasing Embers by James Bennett • Fated by S.G. Browne • Fated by S.G. Browne • So Far From God by Ana Castillo • So Far From God by Ana Castillo • Penelope’s Daughter by Laurel Corona • Penelope’s Daughter by Laurel Corona • The Secret of the Stones by Ernst Dempsey • The Secret of the Stones by Ernst Dempsey • When Halloween was Green • When Halloween was Green by Bernard K. Finnigan by Bernard K. Finnigan • The Lost Sisterhood by Anne Fortier • The Lost Sisterhood by Anne Fortier • Zadayi Red by Caleb Fox • Zadayi Red by Caleb Fox • Norse Mythology by Neil Gaiman • Norse Mythology by Neil Gaiman • Helen of Troy by Margaret George • Helen of Troy by Margaret George • Medea by Kerry Greenwood • Medea by Kerry Greenwood • Sonora and the Eye of the Titans • Sonora and the Eye of the Titans by Travis Halls by Travis Halls • A Plague of Giants by Kevin Hearne • A Plague of Giants by Kevin Hearne • Crazy Cupid Love by Amanda Heger • Crazy Cupid Love by Amanda Heger • Black Leopard, Red Wolf by Marlon James • Black Leopard, Red Wolf by Marlon James • The Stag Lord by Darby Kaye • The Stag Lord by Darby Kaye • Flight of the Golden Harpy by Susan Klaus • Flight of the Golden Harpy by Susan Klaus • Game of Shadows by Erika Lewis • Game of Shadows by Erika Lewis • Five Odd Honors by Jane M. -

Whore Or Hero?: Helen of Troy's Agency and Responsibility from Antiquity to Modern Young Adult Fiction Alicia Dixon University of Mississippi

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2017 Whore or Hero?: Helen of Troy's Agency and Responsibility from Antiquity to Modern Young Adult Fiction Alicia Dixon University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Dixon, Alicia, "Whore or Hero?: Helen of Troy's Agency and Responsibility from Antiquity to Modern Young Adult Fiction" (2017). Honors Theses. 38. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/38 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHORE OR HERO? HELEN OF TROY’S AGENCY AND RESPONSIBILITY FROM ANTIQUITY TO MODERN YOUNG ADULT FICTION by Alicia Michelle Dixon A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2017 Approved by _____________________________________________ Advisor: Dr. Molly Pasco-Pranger _____________________________________________ Reader: Dr. Brad Cook _____________________________________________ Reader: Dr. Steven Skultety © 2017 Alicia Michelle Dixon ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated, in memoriam, to my father, Daniel Dixon. Daddy, I wouldn’t be here without you. You would have sent me to college on the moon, if that was what I wanted, and because of that, you set me up to shoot for the stars. For the past four years, Ole Miss has been exactly where I belong, and much of my work has culminated in this thesis. -

Irony in the Drama: an Essay on Impersonation, Shock, and Catharsis

Irony In The Drama Irony in the Drama: An Essay on Impersonation, Shock, and Catharsis. Contributors: Robert Boies Sharpe - author. Publisher: Greenwood Press. Place of Publication: Westport, CT. Publication Year: 1975 IRONY IN THE DRAMA An Essay on Impersonation, Shock and Catharsis By ROBERT BOIES SHARPE GREENWOOD PRESS, PUBLISHERS WESTPORT, CONNECTICUT -iii- Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Sharpe, Robert Boies, 1897Irony in the drama. Reprint of the ed. published by the University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill. 1. English drama -- History and criticism. 2. Irony in literature. 3. Shakespeare, William, 1564-1616 -- Criticism and interpretation. 4. American drama -- 20th century -- History and criticism. 5. Catharsis. I. Title. [ PR635.I7S5 1974 ] 822'.009 74-8121 ISBN 0-8371-7552-6 Copyright, 1959, by The University of North Carolina Press Originally published in 1959 by The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill Reprinted with the permission of The University of North Carolina Press Reprinted in 1975 by Greenwood Press, a division of Williamhouse-Regency Inc. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 74-8121 ISBN 0-8371-7552-6 Printed in the United States of America -iv- CONTENTS Introduction vii I. What Is a Drama? 3 II. Irony and Impersonation 18 III. The Levels of Impersonation 30 IV. Forms of Irony in Drama 42 V. William Shakespeare, Ironist 52 VI. The Cathartic Process, Shock, and Classical Tragedy 82 VII. The Cathartic Process from the Middle Ages to the Present 104 VIII. A Theory of Comic Shock 121 1 Irony In The Drama IX. Comic Shock and Comic Catharsis in Practice 135 answers, or at least right enough to be useful ones. -

College of Arts and Letters

College of Arts and Letters 86 Curricula and Degrees. The College of Arts and Admission Policies. Admission to the College of College of Arts Letters offers curricula leading to the degree of bach- Arts and Letters takes place at the end of the first elor of fine arts in Art (Studio and Design) and of year. The student body of the College of Arts and and Letters bachelor of arts in: Letters thus comprises sophomores, juniors and American Studies seniors. Anthropology The prerequisite for admission of sophomores The College of Arts and Letters is the oldest, and Art: into the College of Arts and Letters is good standing traditionally the largest, of the four undergraduate Studio at the end of the student’s first year. colleges of the University of Notre Dame. It houses Design The student must have completed at least 24 17 departments and several programs through Art History credit hours and must have satisfied all of the speci- which students at both undergraduate and graduate Classics: fied course requirements of the First Year of Studies levels pursue the study of the fine arts, the humani- Classical Civilization Program: University Seminar; Composition; two se- ties and the social sciences. Latin mester courses in mathematics; two semester courses Greek in natural science; one semester course chosen from Liberal Education. The College of Arts and Let- East Asian Languages and Literatures: history, social science, philosophy, theology, litera- ters provides a contemporary version of a tradi- Chinese ture or fine arts; and two semester courses in physical tional liberal arts educational program. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Starcrossed (Starcrossed #1) by Josephine Angelini Starcrossed (Starcrossed #1)(3) Josephine Angelini

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Starcrossed (Starcrossed #1) by Josephine Angelini Starcrossed (Starcrossed #1)(3) Josephine Angelini. About six years ago the News Store had expanded its horizons and added Kate’s Cakes onto the back, and since then business had exploded. Kate Rogers was, quite simply, a genius with baked goods. She could take anything and make it into a pie, cake, popover, cookie, or muffin. Even universally loathed vegetables like brussels sprouts and broccoli succumbed to Kate’s wiles and became big hits as croissant fillers. Still in her early thirties, Kate was creative and intelligent. When she’d partnered up with Jerry she revamped the back of the News Store and turned it into a haven for the island’s artists and writers, somehow managing to do it without turning up the snob factor. Kate was careful to make sure that anyone who loved baked goods and real coffee—from suits to poets, working-class townies to corporate raiders—would feel comfortable sitting down at her counter and reading a newspaper. She had a way of making everyone feel welcome. Helen adored her. When Helen got to work the next day, Kate was trying to stock a delivery of flour and sugar. It was pathetic. “Lennie! Thank god you’re early. Do you think you could help me . ?” Kate gestured toward the forty-pound sacks. “I got it. No, don’t tug the corner like that, you’ll hurt your back,” Helen warned, rushing to stop Kate’s ineffectual pulling. “Why didn’t Luis do this for you? Wasn’t he working this morning?” Helen asked, referring to one of the other workers on the schedule.