The Tale's Worth Telling: a Thematic Comparison Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elenco Internet Dei Libri11 12 2020

11/12/2020 ELENCO DEI LIBRI DELLA BIBLIOTECA COMUNALE DI VILLANOVA D'ASTI L'ELENCO è un documento in formato PDF in cui ogni riga contiene i dati di un libro disponibile, (salvo giacenza 0 = prestito in corso). I NUOVI ARRIVI (LIBRI NUOVI O ULTIME DONAZIONI) SI TROVANO AD INIZIARE DALLA PRIMA PAGINA Istruzioni per eseguire la ricerca di una parola chiave (cioè un autore, o un titolo, o parole intere parti di esso). Di preferenza evitare parole accentate o apostrofate (Perchè i titoli memorizzati in maiuscolo non le hanno, o possono non averle) Ricerca con ACROBAT READER: fare clic sull'icona della LENTE, (oppure menù MODIFICA -> TROVA). Comparirà una casella in cui scrivere l'occorrenza cercata. Premere AVANTI. Il ritrovamento è mostrato evidenziato in azzurro. Proseguire la ricerca con i Tasti “Avanti” o “Precedente”. Ricerca con un browser internet (come Chrome; Mozilla Firefox; ecc): 1) Fare clic sul tasto con tre lineette a destra della riga di indirizzo del vostro browser, e scegliere TROVA 2) A seconda del browser utilizzato, in un angolo dello schermo si aprirà una casella in cui inserire la parola cercata. 3) Appena si scrive qualcosa, parte automaticamente la ricerca per trovare la prima occorrenza, che sarà evidenziata in colore. 4) Con le freccette poste accanto alla casella, si naviga a tutte le occorrenze successive o precedenti. ProgressivoAnno Codice MatricolaTitolo Sottotitolo 8047 07/12/2020 15:37853.9.CAR27 8047LE IRREGOLARI BUENOS AIRES HORROR TOUR 8046 07/12/2020 15:26 R7.GRD30 8046 CRISTOFORO COLOMBO. VIAGGIATORE SENZA CONFINI 8045 07/12/2020 15:25 R7.GRD29 8045 ENZO FERRARI. -

Senecan Tragedy and Virgil's Aeneid: Repetition and Reversal

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 Senecan Tragedy and Virgil's Aeneid: Repetition and Reversal Timothy Hanford Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/427 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SENECAN TRAGEDY AND VIRGIL’S AENEID: REPETITION AND REVERSAL by TIMOTHY HANFORD A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Classics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 ©2014 TIMOTHY HANFORD All Rights Reserved ii This dissertation has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in Classics in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Ronnie Ancona ________________ _______________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Dee L. Clayman ________________ _______________________________ Date Executive Officer James Ker Joel Lidov Craig Williams Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract SENECAN TRAGEDY AND VIRGIL’S AENEID: REPETITION AND REVERSAL by Timothy Hanford Advisor: Professor Ronnie Ancona This dissertation explores the relationship between Senecan tragedy and Virgil’s Aeneid, both on close linguistic as well as larger thematic levels. Senecan tragic characters and choruses often echo the language of Virgil’s epic in provocative ways; these constitute a contrastive reworking of the original Virgilian contents and context, one that has not to date been fully considered by scholars. -

Dares Phrygius' De Excidio Trojae Historia: Philological Commentary and Translation

Faculteit Letteren & Wijsbegeerte Dares Phrygius' De Excidio Trojae Historia: Philological Commentary and Translation Jonathan Cornil Scriptie voorgedragen tot het bekomen van de graad van Master in de Taal- en letterkunde (Latijn – Engels) 2011-2012 Promotor: Prof. Dr. W. Verbaal ii Table of Contents Table of Contents iii Foreword v Introduction vii Chapter I. De Excidio Trojae Historia: Philological and Historical Comments 1 A. Dares and His Historia: Shrouded in Mystery 2 1. Who Was ‘Dares the Phrygian’? 2 2. The Role of Cornelius Nepos 6 3. Time of Origin and Literary Environment 9 4. Analysing the Formal Characteristics 11 B. Dares as an Example of ‘Rewriting’ 15 1. Homeric Criticism and the Trojan Legacy in the Middle Ages 15 2. Dares’ Problematic Connection with Dictys Cretensis 20 3. Comments on the ‘Lost Greek Original’ 27 4. Conclusion 31 Chapter II. Translations 33 A. Translating Dares: Frustra Laborat, Qui Omnibus Placere Studet 34 1. Investigating DETH’s Style 34 2. My Own Translations: a Brief Comparison 39 3. A Concise Analysis of R.M. Frazer’s Translation 42 B. Translation I 50 C. Translation II 73 D. Notes 94 Bibliography 95 Appendix: the Latin DETH 99 iii iv Foreword About two years ago, I happened to be researching Cornelius Nepos’ biography of Miltiades as part of an assignment for a class devoted to the study of translating Greek and Latin texts. After heaping together everything I could find about him in the library, I came to the conclusion that I still needed more information. So I decided to embrace my identity as a loyal member of the ‘Internet generation’ and began my virtual journey through the World Wide Web in search of articles on Nepos. -

Homer – the Iliad

HOMER – THE ILIAD Homer is the author of both The Iliad and The Odyssey. He lived in Ionia – which is now modern day Turkey – between the years of 900-700 BC. Both of the above epics provided the framework for Greek education and thought. Homer was a blind bard, one who is a professional story teller, an oral historian. Epos or epic means story. An epic is a particular type of story; it involves one with a hero in the midst of a battle. The subject of the poem is the Trojan War which happened approximately in 1200 BC. This was 400 years before the poem was told by Homer. This story would have been read aloud by Homer and other bards that came after him. It was passed down generation to generation by memory. One can only imagine how valuable memory was during that time period – there were no hard drives or memory sticks. On a tangential note, one could see how this poem influenced a culture; to be educated was to memorize a particular set of poems or stories which could be cross-referenced with other people’s memory of those particular stories. The information would be public and not private. The Iliad is one of the greatest stories ever told – a war between two peoples; the Greeks from the West and the Trojans from the East. The purpose of this story is to praise Achilles. The two worlds are brought into focus; the world of the divine order and the human order. The hero of the story is to bring greater order and harmony between these two orders. -

History 101 the Iliad

History 101 The Iliad The Iliad (sometimes referred to as the Song of Ilion or Song of Ilium) is an ancient Greek epic poem in dactylic hexameter, traditionally attributed to Homer. Set during the Trojan War, the ten-year siege of the city of Troy (Ilium) by a coalition of Greek states, it tells of the battles and events during the weeks of a quarrel between King Agamemnon and the warrior Achilles. Although the story covers only a few weeks in the final year of the war, the Iliad mentions or alludes to many of the Greek legends about the siege; the earlier events, such as the gathering of warriors for the siege, the cause of the war, and related concerns tend to appear near the beginning. Then the epic narrative takes up events prophesied for the future, such as Achilles' looming death and the sack of Troy, although the narrative ends before these events take place. However, as these events are prefigured and alluded to more and more vividly, when it reaches an end, the poem has told a more or less complete tale of the Trojan War. The Iliad is paired with something of a sequel, the Odyssey, also attributed to Homer. Along with the Odyssey, the Iliad is among the oldest extant works of Western literature, and its written version is usually dated to around the 8th century BC. Recent statistical modeling based on language evolution gives a date of 760–710 BC. In the standard accepted version, the Iliad contains 15,693 lines; it is written in Homeric Greek, a literary amalgam of Ionic Greek and other dialects. -

T H E R S I T E S

T H E R S I T E S THERSITES: Homer’s Ugliest Man Nathan Dane II with an Afterword by the editors Copyright © 2018 FreeReadPress All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned,or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Los Angeles: FreeReadPress Printed in the United States of America ISBN-13: 978-1724622389 ISBN-10: 1724622382 Thersites How came I here among the Shades, the butt Of Homer’s tongue in life, his adversary in death? How odd to be the object of ridicule, Marked with scorn for my poor body’s faults, Hated for the frankness of my speech! Though from heroic stock, I did not play The hero’s part. My all-too-normal instincts Roused my heart against the selfish kings, But I, poor fool, was tripped by arrogance And stumbled to my doom. I did not know That often men refuse a helping hand And damn their benefactor’s kind intent. I thought to take their part–or was I blinded By my own self-seeking soul? If so, Perhaps I do deserve to rot beyond The earth’s far rim and play a proverb role As Shakespeare’s crude buffoon. And yet if I But had it all to do again, I would. v Nathan Dane II Thersites The day would soon be bright, as the sun was climbing behind the sandstone peaks opposite where we had spent the night. Already the mists in the distant valley below showed tinges of pink and gold. Here and there silver streaks of the winding river threaded their way through green patches to the sea that lay beyond the grim towers of Calydon, the seat of power of Oeneus, my aging uncle. -

Orality, Fluid Textualization and Interweaving Themes

Orality,Fluid Textualization and Interweaving Themes. Some Remarks on the Doloneia: Magical Horses from Night to Light and Death to Life Anton Bierl * Introduction: Methodological Reflection The Doloneia, Book 10 of the Iliad, takes place during the night and its events have been long interpreted as unheroic exploits of ambush and cunning. First the desperate Greek leader Agamemnon cannot sleep and initiates a long series of wake-up calls as he seeks new information and counsel. When the Greeks finally send out Odysseus and Diomedes, the two heroes encounter the Trojan Dolon who intends to spy on the Achaeans. They hunt him down, and in his fear of death, Dolon betrays the whereabouts of Rhesus and his Thracian troops who have arrived on scene late. Accordingly, the focus shifts from the endeavor to obtain new knowledge to the massacre of enemies and the retrieval of won- drous horses through trickery and violence. * I would like to thank Antonios Rengakos for his kind invitation to Thessalo- niki, as well as the editors of this volume, Franco Montanari, Antonios Renga- kos and Christos Tsagalis. Besides the Conference Homer in the 21st Century,I gave other versions of the paper at Brown (2010) and Columbia University (CAM, 2011). I am grateful to the audiences for much useful criticism, partic- ularly to Casey Dué, Deborah Boedeker, Marco Fantuzzi, Pura Nieto Hernan- dez, David Konstan, Kurt Raaflaub and William Harris for stimulating conver- sations. Only after the final submission of this contribution, Donald E. Lavigne granted me insight into his not yet published manuscript “Bad Kharma: A ‘Fragment’ of the Iliad and Iambic Laughter” in which he detects iambic reso- nances in the Doloneia, and I received a reference to M.F. -

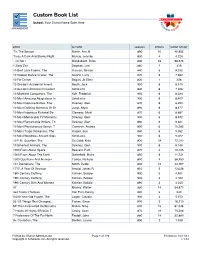

Custom Book List

Custom Book List School: Your District Name Goes Here MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® POINTS WORD COUNT 'Tis The Season Martin, Ann M. 890 10 40,955 'Twas A Dark And Stormy Night Murray, Jennifer 830 4 4,224 ...Or Not? Mandabach, Brian 840 23 98,676 1 Zany Zoo Degman, Lori 860 1 415 10 Best Love Poems, The Hanson, Sharon 840 6 8,332 10 Coolest Dance Crazes, The Swartz, Larry 870 6 7,660 10 For Dinner Bogart, Jo Ellen 820 1 328 10 Greatest Accidental Inventi Booth, Jack 900 6 8,449 10 Greatest American President Scholastic 840 6 7,306 10 Mightiest Conquerors, The Koh, Frederick 900 6 8,034 10 Most Amazing Adaptations In Scholastic 900 6 8,409 10 Most Decisive Battles, The Downey, Glen 870 6 8,293 10 Most Defining Moments Of Th Junyk, Myra 890 6 8,477 10 Most Ingenious Fictional De Clemens, Micki 870 6 8,687 10 Most Memorable TV Moments, Downey, Glen 900 6 8,912 10 Most Remarkable Writers, Th Downey, Glen 860 6 9,321 10 Most Revolutionary Songs, T Cameron, Andrea 890 6 10,282 10 Most Tragic Romances, The Harper, Sue 860 6 9,052 10 Most Wondrous Ancient Sites Scholastic 900 6 9,022 10 P.M. Question, The De Goldi, Kate 830 18 72,103 10 Smartest Animals, The Downey, Glen 900 6 8,148 1000 Facts About Space Beasant, Pam 870 4 10,145 1000 Facts About The Earth Butterfield, Moira 850 6 11,721 1000 Questions And Answers Tames, Richard 890 9 38,950 101 Dalmatians, The Smith, Dodie 830 12 44,767 1777: A Year Of Decision Arnold, James R. -

Homer, Troy and the Turks

4 HERITAGE AND MEMORY STUDIES Uslu Homer, Troy and the Turks the and Troy Homer, Günay Uslu Homer, Troy and the Turks Heritage and Identity in the Late Ottoman Empire, 1870-1915 Homer, Troy and the Turks Heritage and Memory Studies This ground-breaking series examines the dynamics of heritage and memory from a transnational, interdisciplinary and integrated approach. Monographs or edited volumes critically interrogate the politics of heritage and dynamics of memory, as well as the theoretical implications of landscapes and mass violence, nationalism and ethnicity, heritage preservation and conservation, archaeology and (dark) tourism, diaspora and postcolonial memory, the power of aesthetics and the art of absence and forgetting, mourning and performative re-enactments in the present. Series Editors Rob van der Laarse and Ihab Saloul, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands Editorial Board Patrizia Violi, University of Bologna, Italy Britt Baillie, Cambridge University, United Kingdom Michael Rothberg, University of Illinois, USA Marianne Hirsch, Columbia University, USA Frank van Vree, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands Homer, Troy and the Turks Heritage and Identity in the Late Ottoman Empire, 1870-1915 Günay Uslu Amsterdam University Press This work is part of the Mosaic research programme financed by the Netherlands Organisa- tion for Scientific Research (NWO). Cover illustration: Frontispiece, Na’im Fraşeri, Ilyada: Eser-i Homer (Istanbul, 1303/1885-1886) Source: Kelder, Uslu and Șerifoğlu, Troy: City, Homer and Turkey Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Typesetting: Crius Group, Hulshout Editor: Sam Herman Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 94 6298 269 7 e-isbn 978 90 4853 273 5 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789462982697 nur 685 © Günay Uslu / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2017 All rights reserved. -

Masterarbeit

MASTERARBEIT Titel der Masterarbeit „Persephone and Hades Revisited: Modern Retellings of the Myth in Young Adult Literature“ verfasst von Olivia Zajkas, BA angestrebter akademischer Grad Master of Arts (MA) Wien, 2015 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 066 844 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Masterstudium Anglophone Literatures and Cultures Betreut von: Assoz. Prof. Mag. Dr. Susanne Reichl, Privatdoz. “The most common way people give up their power is by thinking they don't have any.” ― Alice Walker “If you’re gonna throw your life away, he’d better have a motorcycle.” ― Lorelai Gilmore Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank my family, my parents and siblings, for their unconditional support over the last few years. Without their help I wouldn’t have been able to achieve this. I would also like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Susanne Reichl, not only for her encouragement and feedback, but also for understanding my passion for this topic. I am also grateful to Dr. Waldemar Zacharasiewicz, who through his kind words strengthened my decision to apply for a Master’s degree in literature (although he most likely forgot about this). Moreover, I have to acknowledge my partner in crime, the Rory to my Lorelai (or vice versa), who has always been there for me on this journey, Steffi. Thank you for everything, where you lead I will follow. All of this would not have been possible without the vital input, encouragement, and support of my friends Peter, Nura, Tami, Connie, Denise, and Sandra. Last but certainly not least, I have to give credit to all the strong female fictional characters I have encountered so far. -

Troy Myth and Reality

Part 1 Large print exhibition text Troy myth and reality Please do not remove from the exhibition This two-part guide provides all the exhibition text in large print. There are further resources available for blind and partially sighted people: Audio described tours for blind and partially sighted visitors, led by the exhibition curator and a trained audio describer will explore highlight objects from the exhibition. Tours are accompanied by a handling session. Booking is essential (£7.50 members and access companions go free) please contact: Email: [email protected] Telephone: 020 7323 8971 Thursday 12 December 2019 14.00–17.00 and Saturday 11 January 2020 14.00–17.00 1 There is also an object handling desk at the exhibition entrance that is open daily from 11.00 to 16.00. For any queries about access at the British Museum please email [email protected] 2 Sponsor’sThe Trojan statement War For more than a century BP has been providing energy to advance human progress. Today we are delighted to help you learn more about the city of Troy through extraordinary artefacts and works of art, inspired by the stories of the Trojan War. Explore the myth, archaeology and legacy of this legendary city. BP believes that access to arts and culture helps to build a more inspired and creative society. That’s why, through 23 years of partnership with the British Museum, we’ve helped nearly five million people gain a deeper understanding of world cultures with BP exhibitions, displays and performances. Our support for the arts forms part of our wider contribution to UK society and we hope you enjoy this exhibition. -

Illinois Classical Studies, Volume I

r m LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN 880 v.l Classics The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return to the library from which it was withdrawn on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for disciplinary action and may result in dismissal from the University. UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN DEC la 76 199^ hwvi (JCTl2«n Mil TO JUL 08 1938 SFP 1 3 19 '9 mi 1 4 15'^1), ^JUL s 5 ^f FES 2 i U84 JAIIZ2 m 3 1939 L161 — O-1096 ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES, VOLUME I ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME I 1976 Miroslav Marcovich, Editor UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS Urbana Chicago London [976 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois Manufactured in the United States of America ISBN: 0-252-00516-3 •r or CLASSICS Preface Illinois Classical Studies (ICS) is a serial publication of the Classics Depart- ments of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and Chicago Circle which contains the results of original research dealing with classical antiquity and with its impact upon Western culture. ICS welcomes scholarly contributions dealing with any topic or aspect of Greek and/or Roman literature, language, history, art, culture, philosophy, religion, and the like, as well as with their transmission from antiquity through Byzantium or Western Europe to our time. ICS is not limited to contributions coming from Illinois. It is open to classicists of any flag or school of thought. In fact, of sixteen contributors to Volume I (1976), six are from Urbana, two from Chicago, six from the rest of the country, and two from Europe.