A Molecular Phylogeny Shows the Single Origin of the Pyrenean Subterranean Trechini Ground Beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BIENVENUE EN SOULE Hunki Jin Xiberoan « Tous Les Souletins Vous Le Diront : La Soule, C’Est Le Vrai Pays Basque, Celui Qui N’A Jamais Cédé Aux Sirènes Du Tourisme

Dossier technique Routes de charme du Pays Basque à vélo Document non contractuel Voyage itinérant de 7 jours/6 nuits à vélo tout chemin (vtc) au départ de Mauléon, capitale de la province basque de Soule. Vous pédalez à travers une campagne magnifique, sur des routes secondaires peu fréquentées... BIENVENUE EN SOULE Hunki jin Xiberoan « Tous les Souletins vous le diront : la Soule, c’est le vrai Pays Basque, celui qui n’a jamais cédé aux sirènes du tourisme. Enfin, il ne faut pas exagérer non plus, ce n’est pas un monde de sauvages. Toutefois, la Soule ne se livre pas tout de suite. Il faut savoir apprivoiser ce pays, car on est loin du Pays basque des cartes postales. à tel point que si vous aimez et comprenez la Soule, le reste de la région vous paraîtra un peu fade. La Soule, c’est la vallée du Saison, affluent du gave de Pau, un pays isolé, pas facile d’accès. On peut sans doute trouver des dizaines de justifications à cet isolement, mais la meilleure, c’est une hôtelière de Tardets qui nous l’a donnée : « Nous, à part le champagne, il ne nous manque rien», tant il est vrai que la Soule est un régal pour les yeux et les papilles.» www.routard.com 1 Votre séjour Jour 1 : Mauléon Capitale de la province de Soule. Bourg de 3400 habitants dominé par son château féodal du XIIème siècle, Mauléon est également une cité ouvrière dans laquelle perdure la fabrication artisanale de l’espadrille. Dîner et nuit au Domaine Agerria***. -

Green-Tree Retention and Controlled Burning in Restoration and Conservation of Beetle Diversity in Boreal Forests

Dissertationes Forestales 21 Green-tree retention and controlled burning in restoration and conservation of beetle diversity in boreal forests Esko Hyvärinen Faculty of Forestry University of Joensuu Academic dissertation To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Forestry of the University of Joensuu, for public criticism in auditorium C2 of the University of Joensuu, Yliopistonkatu 4, Joensuu, on 9th June 2006, at 12 o’clock noon. 2 Title: Green-tree retention and controlled burning in restoration and conservation of beetle diversity in boreal forests Author: Esko Hyvärinen Dissertationes Forestales 21 Supervisors: Prof. Jari Kouki, Faculty of Forestry, University of Joensuu, Finland Docent Petri Martikainen, Faculty of Forestry, University of Joensuu, Finland Pre-examiners: Docent Jyrki Muona, Finnish Museum of Natural History, Zoological Museum, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland Docent Tomas Roslin, Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, Division of Population Biology, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland Opponent: Prof. Bengt Gunnar Jonsson, Department of Natural Sciences, Mid Sweden University, Sundsvall, Sweden ISSN 1795-7389 ISBN-13: 978-951-651-130-9 (PDF) ISBN-10: 951-651-130-9 (PDF) Paper copy printed: Joensuun yliopistopaino, 2006 Publishers: The Finnish Society of Forest Science Finnish Forest Research Institute Faculty of Agriculture and Forestry of the University of Helsinki Faculty of Forestry of the University of Joensuu Editorial Office: The Finnish Society of Forest Science Unioninkatu 40A, 00170 Helsinki, Finland http://www.metla.fi/dissertationes 3 Hyvärinen, Esko 2006. Green-tree retention and controlled burning in restoration and conservation of beetle diversity in boreal forests. University of Joensuu, Faculty of Forestry. ABSTRACT The main aim of this thesis was to demonstrate the effects of green-tree retention and controlled burning on beetles (Coleoptera) in order to provide information applicable to the restoration and conservation of beetle species diversity in boreal forests. -

The Coume Ouarnède System, a Hotspot of Subterranean Biodiversity in Pyrenees (France)

diversity Article The Coume Ouarnède System, a Hotspot of Subterranean Biodiversity in Pyrenees (France) Arnaud Faille 1,* and Louis Deharveng 2 1 Department of Entomology, State Museum of Natural History, 70191 Stuttgart, Germany 2 Institut de Systématique, Évolution, Biodiversité (ISYEB), UMR7205, CNRS, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Sorbonne Université, EPHE, 75005 Paris, France; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Located in Northern Pyrenees, in the Arbas massif, France, the system of the Coume Ouarnède, also known as Réseau Félix Trombe—Henne Morte, is the longest and the most complex cave system of France. The system, developed in massive Mesozoic limestone, has two distinct resur- gences. Despite relatively limited sampling, its subterranean fauna is rich, composed of a number of local endemics, terrestrial as well as aquatic, including two remarkable relictual species, Arbasus cae- cus (Simon, 1911) and Tritomurus falcifer Cassagnau, 1958. With 38 stygobiotic and troglobiotic species recorded so far, the Coume Ouarnède system is the second richest subterranean hotspot in France and the first one in Pyrenees. This species richness is, however, expected to increase because several taxonomic groups, like Ostracoda, as well as important subterranean habitats, like MSS (“Milieu Souterrain Superficiel”), have not been considered so far in inventories. Similar levels of subterranean biodiversity are expected to occur in less-sampled karsts of central and western Pyrenees. Keywords: troglobionts; stygobionts; cave fauna Citation: Faille, A.; Deharveng, L. The Coume Ouarnède System, a Hotspot of Subterranean Biodiversity in Pyrenees (France). Diversity 2021, 1. Introduction 13 , 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/ Stretching at the border between France and Spain, the Pyrenees are known as one d13090419 of the subterranean hotspots of the world [1]. -

Téléchargez Notre Plaquette

Ils nous font confiance Au service de l'eau et de l'environnement En Affermage, le Syndicat d’Alimentation en Eau Potable (SAEP) du Pays de Soule (Pyrénées Atlantiques), a confié à LAGUN la production et la distribution d’eau potable : • 38 communes en milieu rural, • 4700 abonnés en habitat dispersé, • 1000 kms de canalisations, • 3 unités de production d’eau potable, • 48 réservoirs, 6 bâches de reprises et 20 surpresseurs, • 1 million de m3 produits. Nos abonnés se répartissent entre particuliers et agriculteurs mais également des industriels, notamment agro-alimentaires, avec plusieurs fromageries de taille significative. Plus de 30 communes pour des prestations de services à la carte (recherche de fuites, entretien de réseaux, relevé de compteurs, installation et entretien de systèmes de télégestion, facturation d'assainissement, contrôle et entretien de poteaux incendie...) : Accous, Aramits, Bedous, Bidos, Borce, Issor, Osse en Aspe, Sarrance, Aussurucq, Garindein, Lanne, Licq Atherey, Montory, Ordiarp, Commission syndicale du Pays de Soule, Lohitzun Oyhercq, Chéraute, Gotein-Libarrenx, Berrogain Larruns, Moncayolle, Viodos Abense de Bas, Alçay, Sauguis, Lacarry, Barcus, Alos Sibas Abense, Menditte, Ainharp, Espès-Undurein, Tardets-Sorholus, Musculdy… Route d'Alos - B.P. 10 - 64470 Tardets - R.C.S. Pau 045 580 222 Tel. 05 59 28 68 08 - Fax. 05 59 28 68 09 www.lagun-environnement.fr - [email protected] www.lagun-environnement.fr Une expertise reconnue La distribution rigoureuse de l'eau, En prestation de services, les besoins croissants en pour les collectivités, entreprises assainissement, le contrôle de la et particuliers qualité et des installations sont de Pour répondre à des besoins précis d'intervention véritables préoccupations pour les sur les réseaux d’eau ou d’assainissement, LAGUN propose également des services "à la collectivités. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

Coleoptera) Deposited in the Natural History Museum of Barcelona, Spain

Arxius de Miscel·lània Zoològica, 12(2014): 13–82 ISSN:Viñolas 1698 & –Masó0476 The collection of type specimens of the family Carabidae (Coleoptera) deposited in the Natural History Museum of Barcelona, Spain A. Viñolas & G. Masó Viñolas, A. & Masó, G., 2014. The collection of type specimens of the family Carabidae (Coleoptera) deposited in the Natural History Museum of Barcelona, Spain. Arxius de Miscel·lània Zoològica, 12: 13–82. Abstract The collection of type specimens of the family Carabidae (Coleoptera) deposited in the Natural History Museum of Barcelona, Spain.— The type collection of the family Carabidae (Coleop- tera) deposited in the Natural History Museum of Barcelona, Spain, has been organised, revised and documented. It contains 430 type specimens belonging to 155 different taxa. Of note are the large number of hypogean species, the species of Cicindelidae from Asenci Codina’s collection, and the species of Harpalinae extracted from Jacques Nègre’s collec- tion. In this paper we provide all the available information related to these type specimens. We therefore provide the following information for each taxon, species or subspecies: the original and current taxonomic status, original citation of type materials, exact transcription of original labels, and preservation condition of specimens. Moreover, the differences between original descriptions and labels are discussed. When a taxonomic change has occurred, the references that examine those changes are included at the end of the taxa description. Key words: Collection type, Coleoptera, Carabidae taxonomic revision family, Ground beetles. Resumen La colección de ejemplares tipo de la familia Carabidae(Coleoptera) depositados en el Museo de Ciencias Naturales de Barcelona, España.— Se ha organizado, revisado y documentado la colección de especímenes tipo de la familia Carabidae (Coleoptera) de- positados en el Museo de Ciencias Naturales de Barcelona. -

De La Península Ibérica Catalogue of the Carabidae (Coleoptera) of the Iberian Peninsula

Catálogo de los Carabidae (Coleoptera) de la Península Ibérica Catalogue of the Carabidae (Coleoptera) of the Iberian Peninsula José Serrano MONOGRAFÍAS SEA, vol. 9 ZARAGOZA, 2003 a Dedicatoria A mi mujer, Bárbara y a mis hijos José Enrique y Antonio. Por todo. Índice Prólogo ......................................................................... 5 Agradecimiento................................................................... 6 Notas a las distintas partes de la obra................................................... 7 El catálogo...................................................................... 11 Cambio nomenclatural ............................................................ 82 Las novedades................................................................... 83 Relación sintética de la Sistemática empleada y estadísticas del catálogo....................... 85 Los mapas de las regiones naturales de la Península Ibérica................................. 91 La bibliografía ................................................................... 93 Índice taxonómico............................................................... 107 Index Foreword........................................................................ 5 Acknowledgements................................................................ 6 Notes to the the chapters of this work .................................................. 7 The catalogue ................................................................... 11 Proposal of nomenclatural change................................................... -

![Catálogo Electrónico De Los Cicindelidae Y Carabidae De La Península Ibérica (Coleoptera, Caraboidea) [Versión 12•2020]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5571/cat%C3%A1logo-electr%C3%B3nico-de-los-cicindelidae-y-carabidae-de-la-pen%C3%ADnsula-ib%C3%A9rica-coleoptera-caraboidea-versi%C3%B3n-12-2020-345571.webp)

Catálogo Electrónico De Los Cicindelidae Y Carabidae De La Península Ibérica (Coleoptera, Caraboidea) [Versión 12•2020]

Monografías electrónicas SEA, vol. 9 (2020) ▪ Sociedad Entomológica Aragonesa (S.E.A.) 1 Catálogo electrónico de los Cicindelidae y Carabidae de la Península Ibérica (Coleoptera, Caraboidea) [Versión 12•2020] José Serrano Tercera parte: Bibliografía Para facilitar el acceso a la información y la localización de obras, la presente sección se divide en dos bloques. En el primero se reproduce el listado bibliográfico recogido hasta 2013 en el anterior Catálogo impreso del autor. Se incluye la numeración original. En el segundo bloque (página 35 de esta sección) se incluye las obras posteriores y se subsanan algunas ausencias anteriorres a 2013. 1. Bibliografía incluida en SERRANO J. (2013) New catalogue of the family Carabidae of the Iberian Peninsula (Coleoptera). Ediciones de la Universidad de Murcia, 192 pp. Obras de conjunto sobre la taxonomía de los Carabidae de la Península Ibérica, Francia y Marruecos / General works on the taxonomy of the family Carabidae from the Iberian Pen‐ insula, France and Morocco 1. ANTOINE M. 1955-1962. Coléoptères Carabiques du Maroc. Mem. Soc. Sci. Nat. Phys. Maroc (N.S. Zoologie) Rabat 1 (1955, 1er partie): 1-177; 3 (1957, 2ème partie): 178-314; 6 (1959, 3ème partie): 315-464; 8 (1961, 4ème partie): 467-537; 9 (1962, 5ème partie): 538-692. 2. DE LA FUENTE J.M. 1927. Tablas analíticas para la clasificación de los coleópteros de la Península Ibérica. Adephaga: 1 Cicindelidae, 11 Carabidae. 1. Bosch, Barcelona, 415 pp. 3. JEANNEL R. 1941-1949. Coléoptères Carabiques. Faune de France, 39 (1941): 1-571; 40 (1942): 572-1173; 51 (1949, Supplément): 1- 51. Lechevalier, París. -

Quaderni Del Museo Civico Di Storia Naturale Di Ferrara

ISSN 2283-6918 Quaderni del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Ferrara Anno 2018 • Volume 6 Q 6 Quaderni del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Ferrara Periodico annuale ISSN. 2283-6918 Editor: STEFA N O MAZZOTT I Associate Editors: CARLA CORAZZA , EM A N UELA CAR I A ni , EN R ic O TREV is A ni Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Ferrara, Italia Comitato scientifico / Advisory board CE S ARE AN DREA PA P AZZO ni FI L ipp O Picc OL I Università di Modena Università di Ferrara CO S TA N ZA BO N AD im A N MAURO PELL I ZZAR I Università di Ferrara Ferrara ALE ss A N DRO Min ELL I LU ci O BO N ATO Università di Padova Università di Padova MAURO FA S OLA Mic HELE Mis TR I Università di Pavia Università di Ferrara CARLO FERRAR I VALER I A LE nci O ni Università di Bologna Museo delle Scienze di Trento PI ETRO BRA N D M AYR CORRADO BATT is T I Università della Calabria Università Roma Tre MAR C O BOLOG N A Nic KLA S JA nss O N Università di Roma Tre Linköping University, Sweden IRE N EO FERRAR I Università di Parma In copertina: Fusto fiorale di tornasole comune (Chrozophora tintoria), foto di Nicola Merloni; sezione sottile di Micrite a foraminiferi planctonici del Cretacico superiore (Maastrichtiano), foto di Enrico Trevisani; fiore di digitale purpurea (Digitalis purpurea), foto di Paolo Cortesi; cardo dei lanaioli (Dipsacus fullonum), foto di Paolo Cortesi; ala di macaone (Papilio machaon), foto di Paolo Cortesi; geco comune o tarantola (Tarentola mauritanica), foto di Maurizio Bonora; occhio della sfinge del gallio (Macroglossum stellatarum), foto di Nicola Merloni; bruco della farfalla Calliteara pudibonda, foto di Maurizio Bonora; piumaggio di pernice dei bambù cinese (Bambusicola toracica), foto dell’archivio del Museo Civico di Lentate sul Seveso (Monza). -

Lignes Régulières

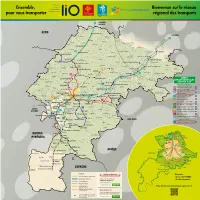

Ensemble, Bienvenue sur le réseau pour vous transporter régional des transports SAMATAN TOULOUSE Boissède Molas GERS TOULOUSE Puymaurin Ambax Sénarens Riolas Nénigan D 17 Pouy-de-Touges Lunax Saint-Frajou Gratens Péguilhan Fabas 365 Castelnau-Picampeau Polastron Latte-Vigordane Lussan-Adeilhac Le Fousseret Lacaugne Eoux Castéra-Vignoles Francon Rieux-Volvestre Boussan Latrape 342 Mondavezan Nizan-Gesse Lespugue 391 D 62 Bax Castagnac Sarrecave Marignac-Laspeyres Goutevernisse Canens Sarremezan 380 Montesquieu-Volvestre 344 Peyrouzet D 8 Larroque Saint- LIGNES Christaud Gouzens Cazaril-Tamboures DÉPARTEMENTALES Montclar-de-Comminges Saint-Plancard Larcan SECTEUR SUD Auzas Le Plan D 5 320 Lécussan Lignes régulières Sédeilhac Sepx Montberaud Ausseing 342 L’ISLE-EN-DODON - SAINT-GAUDENS Le Cuing Lahitère 344 BOULOGNE - SAINT-GAUDENS Franquevielle Landorthe 365 BOULOGNE - L'ISLE-EN-DODON - Montbrun-Bocage SAMATAN - TOULOUSE Les Tourreilles 379 LAVELANET - MAURAN - CAZÈRES 394 D 817 379 SAINT-GAUDENS 397 380 CAZÈRES - NOÉ - TOULOUSE D 117 391 ALAN - AURIGNAC - SAINT-GAUDENS Touille 392 MONCAUP - ASPET - SAINT-GAUDENS His 393 392 Ganties MELLES - SAINT-BÉAT - SAINT-GAUDENS TARBES D 9 Rouède 394 LUCHON - MONTRÉJEAU - SAINT-GAUDENS N 125 398 BAYONNE 395 LES(Val d’Aran) - BARBAZAN - SAINT-GAUDENS Castelbiague Estadens 397 MANE - SAINT-GAUDENS Saleich 398 MONTRÉJEAU - BARBAZAN - SAINT-GAUDENS Chein-Dessus SEPTEMBRE 2019 - CD31/19/7/42845 395 393 Urau Francazal SAINT-GIRONS Navette SNCF D 5 Arbas 320 AURIGNAC - SAINT-MARTORY - BOUSSENS SNCF Fougaron -

Pyrenees Atlantiques

Observatoire national des taxes foncières sur les propriétés bâties 13 ème édition (2019) : période 2008 – 2013 - 2018 L’observatoire UNPI des taxes foncières réalise ses estimations à partir de données issues du portail internet de la Direction générale des finances publiques (https://www.impots.gouv.fr) ou de celui de la Direction générale des Collectivités locales (https://www.collectivites-locales.gouv.fr). En cas d’erreur due à une information erronée ou à un problème dans l’interprétation des données, l’UNPI s’engage à diffuser sur son site internet les données corrigées. IMPORTANT ! : les valeurs locatives des locaux à usage professionnel ayant été réévaluées pour le calcul de l’impôt foncier en 2017, nos chiffres d’augmentation ne sont valables tels quels que pour les immeubles à usage d’habitation. Précautions de lecture : Nos calculs d’évolution tiennent compte : - de la majoration légale des valeurs locatives , assiette de la taxe foncière (même sans augmentation de taux, les propriétaires subissent une augmentation de 4,5 % entre 22013 et 2018, et 14,6 % entre 2008 et 2018) ; - des taxes annexes à la taxe foncière (taxe spéciale d’équipement, TASA, et taxe GEMAPI), à l’exception de la taxe d’enlèvement des ordures ménagères (TEOM). Précisions concernant les taux départementaux 2008 : En 2011 la part régionale de taxe foncière a été transférée au département. Pour comparer avec 2008, nous additionnons donc le taux départemental et le taux régional de 2008. Par ailleurs, nos calculs d’évolution tiennent compte du fait que, dans le cadre de cette réforme, les frais de gestion de l’Etat sont passés de 8 % à 3 % du montant de la taxe foncière, le produit des 5 % restants ayant été transféré aux départements sous la forme d’une augmentation de taux. -

Liste Des Services D'aide À Domicile

14/04/2015 LISTE DES SERVICES D'AIDE À DOMICILE pouvant intervenir auprès des personnes âgées bénéficiaires de l'Allocation Personnalisée d'Autonomie (A.P.A.), des adultes handicapées bénéficiaires de la Prestation de Compensation du Handicap (P.C.H.) et pour certains, auprès des bénéficiaires de l'aide ménagère au titre de l'aide sociale légale départementale A Habilitation à l'aide sociale départementale www.cg64.fr TI = Type d'interventions réalisables u AS = Service prestataire d'aide à domicile pouvant intervenir auprès des P = Prestataire -- M = Mandataire t bénéficiaires de l'aide sociale départementale Pour plus d'information, voir : Choisir un mode d'intervention . C Code AS Nom du service Adresse Ville Téléphone TI Territoire d'intervention G Postal CCAS Hôtel de ville P Ville d’ANGLET A AS 64600 ANGLET 05 59 58 35 23 Centre Communal d'Action Sociale Place Charles de Gaulle M Département des Pyrénées-Atlantiques Uniquement en garde de nuit itinérante Association 12, rue Jean Hausseguy A AS 64600 ANGLET 05 59 03 63 30 P Communauté d’agglomération du BAB (BIARRITZ, Les Lucioles BP 441 BAYONNE, ANGLET) et périphérie proche Association P 95, avenue de Biarritz 64600 ANGLET 05 59 41 22 98 Département des Pyrénées-Atlantiques Côte Basque Interservices (ACBI) M Association P 3, rue du pont de l'aveugle 64600 ANGLET 05 59 03 53 31 Département des Pyrénées-Atlantiques Services aux Particuliers (ASAP) M Association 12, rue Jean Hausseguy P 64600 ANGLET 05 59 03 63 30 Département des Pyrénées-Atlantiques Garde à Domicile BP 441 M Centre