Advertising As Capitalist Realism Michael Schudson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advertising and the Public Interest. a Staff Report to the Federal Trade Commission. INSTITUTION Federal Trade Commission, New York, N.Y

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 074 777 EM 010 980 AUTHCR Howard, John A.; Pulbert, James TITLE Advertising and the Public Interest. A Staff Report to the Federal Trade Commission. INSTITUTION Federal Trade Commission, New York, N.Y. Bureau of Consumer Protection. PUB EATE Feb 73 NOTE 575p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$19.74 DESCRIPTORS *Broadcast Industry; Commercial Television; Communication (Thought Transfer); Consumer Economics; Consumer Education; Federal Laws; Federal State Relationship; *Government Role; *Investigations; *Marketing; Media Research; Merchandise Information; *Publicize; Public Opinj.on; Public Relations; Radio; Television IDENTIFIERS Federal Communications Commission; *Federal Trade Commission; Food and Drug Administration ABSTRACT The advertising industry in the United States is thoroughly analyzed in this comprehensive, report. The report was prepared mostly from the transcripts of the Federal Trade Commission's (FTC) hearings on Modern Advertising Practices.' The basic structure of the industry as well as its role in marketing strategy is reviewed and*some interesting insights are exposed: The report is primarily concerned with investigating the current state of the art, being prompted mainly by the increased consumes: awareness of the nation and the FTC's own inability to set firm guidelines' for effectively and consistently dealing with the industry. The report points out how advertising does its job, and how it employs sophisticated motivational research and communications methods to reach the wide variety of audiences available. The case of self-regulation is presented with recommendationS that the FTC be particularly harsh in applying evaluation criteria tochildren's advertising. The report was prepared by an outside consulting firm. (MC) ADVERTISING AND THE PUBLIC INTEREST A Staff Report to the Federal Trade Commission by John A. -

Supran Oreskes 2017 Environ. Res. Lett. 12 084019

Home Search Collections Journals About Contact us My IOPscience Assessing ExxonMobil’s climate change communications (1977–2014) This content has been downloaded from IOPscience. Please scroll down to see the full text. 2017 Environ. Res. Lett. 12 084019 (http://iopscience.iop.org/1748-9326/12/8/084019) View the table of contents for this issue, or go to the journal homepage for more Download details: IP Address: 128.223.223.76 This content was downloaded on 29/08/2017 at 00:56 Please note that terms and conditions apply. You may also be interested in: Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming John Cook, Naomi Oreskes, Peter T Doran et al. Public interest in climate change over the past decade and the effects of the ‘climategate’ media event William R L Anderegg and Gregory R Goldsmith Quantifying the consensus on anthropogenic global warming in the scientific literature John Cook, Dana Nuccitelli, Sarah A Green et al. Global warming and clean electricity D Bodansky National contributions to observed global warming H Damon Matthews, Tanya L Graham, Serge Keverian et al. The climate change consensus extends beyond climate scientists J S Carlton, Rebecca Perry-Hill, Matthew Huber et al. ‘Ye Olde Hot Aire’: reporting on human contributions to climate change in the UK tabloidpress Maxwell T Boykoff and Maria Mansfield Simulating the Earth system response to negative emissions C D Jones, P Ciais, S J Davis et al. Climate change: seeking balance in media reports Chris Huntingford and David Fowler Environ. Res. Lett. 12 (2017) 084019 https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa815f LETTER Assessing ExxonMobil’s climate change communications OPEN ACCESS (1977–2014) RECEIVED 22 June 2017 Geoffrey Supran1 and Naomi Oreskes REVISED Department of the History of Science, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, United States of America 17 July 2017 1 Author to whom any correspondence should be addressed. -

California Budget Woes & Tax Changes Today's Agenda

California Budget Woes & Tax Changes Today’s Agenda • The Political Environment after the May 19 Ballot • Accelerating Cash Payments • Estimated Payments Accelerated • LLC Fee Accelerated • 20% Understatement Penalty for $1M understatements • NOL Deduction Changes (suspension and conformity) • Credit Utilization and Assignment (suspension and future assignment in unitary group) • New Credits – Motion Picture & New Hire for Small Business California Budget Woes & Tax Changes Today’s Agenda (continued) • Factor Presence Nexus Adopted • Cost of Performance Rules change to Market Based Sourcing • Joyce rule replaced by Finnigan • Elective Single Sales Factor • Treasury Proceeds Defined in Statute • Sales and Use Tax Provisions • Notable Miscellaneous Provisions The Political Environment •On May 19th, the Voters Spoke •Spending Cuts are The Agenda •California runs out of cash by July 15th even with acceleration of payments •No Tax Increases; No 2/3 Vote •Enacted Changes are at Risk of Repeal Elective Single Sales Factor Credit Assignment NOL Carryback 20% Understatement Penalty Existing provisions of both Personal Income Tax (PIT) Law and Corporate Tax Law impose a penalty on a taxpayer that underpays estimated Income tax. SBX1 28 imposes a penalty on taxpayers subject to corporation tax law equal to 20% of the understatement of tax in excess of $1 million for any tax year Note: This is an understatement penalty, not an underpayment penalty Definition of “Understatement:” “The amount by which the tax imposed … exceeds the amount of tax shown on an original return or shown on an amended return filed on or before the original or extended due date of the return for any tax year.” (Rev. -

Ambiguity and the Search for Meaning: English and American Studies at the Beginning of the 21St Century

Ambiguity and the Search for Meaning: English and American Studies at the Beginning of the 21st Century Volume 1: Literature Ambiguity and the Search for Meaning: English and American Studies at the Beginning of the 21st Century Volume 1: Literature Edited by Monika Coghen Zygmunt Mazur Beata Piątek Jagiellonian University Press The publication of this volume was supported by the Faculty of Philology of the Jagiellonian University, and the Institute of English Philology, Jagiellonian University. BOARD OF REVIEWERS Teresa Bela Joelle Biele Julie Campbell Benjamin Colbert Marta Gibińska-Marzec Aleksandra Kędzierska David Malcolm Irena Przemęcka Krystyna Stamirowska-Sokołowska Lisa Vargo Anna Walczuk COVER DESIGN Marcin Klag TYPESETTING Sebastian Leśniewski TECHNICAL EDITOR Mirosław Ruszkiewicz © Copyright by Monika Coghen, Zygmunt Mazur, Beata Piątek & Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego First edition, Kraków 2010 No part of this book may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the Publisher. ISBN 978-83-233-3117-9 I WYDAWNICTWO] UNIWERSYTETU JAGIELLOŃSKIEGO www.wuj.pl Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego Redakcja: ul. Michałowskiego 9/2, 31-126 Kraków tel. 12-631-18-81, 12-631-18-82, fax 12-631-18-83 Dystrybucja: tel. 12-631-01-97, tel./fax 12-631-01-98 tel. kom. 0506-006-674, e-mail: [email protected] Konto: PEKAO SA, nr 80 1240 4722 1111 0000 4856 3325 A Bibl. Jagiell. ■ Contents Preface................................................................................................................................... 9 ELINOR SHAFFER Seven Times Seven Types of Ambiguity: William Empson and Twentieth-Century Criticism....................................................................................... 11 ROBERT REHDER Meaning and Change of Form: Eliot, Pound and Niedecker............................................ -

What Lies Beneath 2 FOREWORD

2018 RELEASE THE UNDERSTATEMENT OF EXISTENTIAL CLIMATE RISK BY DAVID SPRATT & IAN DUNLOP | FOREWORD BY HANS JOACHIM SCHELLNHUBER BREAKTHROUGHONLINE.ORG.AU Published by Breakthrough, National Centre for Climate Restoration, Melbourne, Australia. First published September 2017. Revised and updated August 2018. CONTENTS FOREWORD 02 INTRODUCTION 04 RISK UNDERSTATEMENT EXCESSIVE CAUTION 08 THINKING THE UNTHINKABLE 09 THE UNDERESTIMATION OF RISK 10 EXISTENTIAL RISK TO HUMAN CIVILISATION 13 PUBLIC SECTOR DUTY OF CARE ON CLIMATE RISK 15 SCIENTIFIC UNDERSTATEMENT CLIMATE MODELS 18 TIPPING POINTS 21 CLIMATE SENSITIVITY 22 CARBON BUDGETS 24 PERMAFROST AND THE CARBON CYCLE 25 ARCTIC SEA ICE 27 POLAR ICE-MASS LOSS 28 SEA-LEVEL RISE 30 POLITICAL UNDERSTATEMENT POLITICISATION 34 GOALS ABANDONED 36 A FAILURE OF IMAGINATION 38 ADDRESSING EXISTENTIAL CLIMATE RISK 39 SUMMARY 40 What Lies Beneath 2 FOREWORD What Lies Beneath is an important report. It does not deliver new facts and figures, but instead provides a new perspective on the existential risks associated with anthropogenic global warming. It is the critical overview of well-informed intellectuals who sit outside the climate-science community which has developed over the last fifty years. All such expert communities are prone to what the French call deformation professionelle and the German betriebsblindheit. Expressed in plain English, experts tend to establish a peer world-view which becomes ever more rigid and focussed. Yet the crucial insights regarding the issue in question may lurk at the fringes, as BY HANS JOACHIM SCHELLNHUBER this report suggests. This is particularly true when Hans Joachim Schellnhuber is a professor of theoretical the issue is the very survival of our civilisation, physics specialising in complex systems and nonlinearity, where conventional means of analysis may become founding director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate useless. -

Twisted Trails of the Wold West by Matthew Baugh © 2006

Twisted Trails of the Wold West By Matthew Baugh © 2006 The Old West was an interesting place, and even more so in the Wold- Newton Universe. Until fairly recently only a few of the heroes and villains who inhabited the early western United States had been confirmed through crossover stories as existing in the WNU. Several comic book miniseries have done a lot to change this, and though there are some problems fitting each into the tapestry of the WNU, it has been worth the effort. Marvel Comics’ miniseries, Rawhide Kid: Slap Leather was a humorous storyline, parodying the Kid’s established image and lampooning westerns in general. It is best known for ‘outing’ the Kid as a homosexual. While that assertion remains an open issue with fans, it isn’t what causes the problems with incorporating the story into the WNU. What is of more concern are the blatant anachronisms and impossibilities the story offers. We can accept it, but only with the caveat that some of the details have been distorted for comic effect. When the Rawhide Kid is established as a character in the Wold-Newton Universe he provides links to a number of other western characters, both from the Marvel Universe and from classic western novels and movies. It draws in the Marvel Comics series’ Blaze of Glory, Apache Skies, and Sunset Riders as wall as DC Comics’ The Kents. As with most Marvel and DC characters there is the problem with bringing in the mammoth superhero continuities of the Marvel and DC universes, though this is not insurmountable. -

KERMIT ROOSEVELT LECTURE: OFFICER TRAINING and EDUCATION by General William R

THE PROFESSIONAL JOURNAL OF THE US ARMY Published by us ARMY COMMAND AND GENERAL STAFF COLLEGE Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 66027·6910 HONORABLE JOHN O. MARSH JR. secretary of the Army LIEUTENANT GENERAL CARL E. VUONO Commandant MAJOR GENERAL DAVE R. PALMER Deputy Commandant MILITARY REVIEW STAFF Lieutenant Colonel Dallas Van Hoose Jr., Editor in Chief Mrs. Patricia L. Wilson, Secretary FEATURES: Mr. Phillip R. DavIs, Books Editor/German Trans· lator PRODUCTION STAFF: Mrs. Dixie R. Dominguez, Production Editor; Mr. Charles Ivie, Art and Design; Mrs. Betty J. Spiewak, Layout and Design; Mrs. Patncia H. Norman, Manuscript/Index Editor; Mrs. Sherry L. LewIs, Books/ Editonal Assistant; Mr. Amos W. Gallaway, Printing 01· ficer LATIN·AMERICAN EDITIONS: Lieutenant Colonel Gary L. Hoebeke, Editor SPANISH·AMERICAN EDITION: Mr. Raul Aponte and Mrs. Alxa L. Diaz, Editors; Mrs Winona E. Stroble, Edllonai Assistant BRAZILIAN EDITION: Lieutenant Colonel Jayme dos San· tos Taddei, Brazilian Army Editor; Mr. Almerisio B. Lopes, Editor CIRCULATION: Captain George Cassi, Business Manager; Staff Sergeant William H. Curtis, Administration; Mrs. Merriam L. Clark and Mrs. EUnice E. Overfield, SubSCrip tions MR ADVISORY BOARD: Colonel Howard S. Paris, Depart· ment 01 Academic Operations; Colonel Stewart Sherard, Center lor Army Leadership; Colonel I. C. Manderson, Department of Combat Support; Colonel Joe S. Johnson Jr., Department 01 Joint and Combined Operations; Colo· nel John F. Orndorff, Department 01 Tactics; Colonel Louis D, F. FrascM, Combat Studies Institute; Dr. Bruce W. Menni John F. MOrrison Chair of Military History; Colonel Hutchinson, Reserve Adviser Military Review VOLUME LXIV OCTOBER 1984 NO 10 CONTENTS PAGE 2 RIDE TO THE RIVER OF DEATH: CAVALRY OPERATIONS IN THE CHICKAMAUGA CAMPAIGN by Malar Jerry D. -

Humorous Advertisements and Their Effectiveness Among Customers with Different Motivational Values

HUMOROUS ADVERTISEMENTS AND THEIR EFFECTIVENESS AMONG CUSTOMERS WITH DIFFERENT MOTIVATIONAL VALUES Judith Elbers Faculty of Behavioral Sciences Master Thesis Communication Science Dr. S. M. Hegner Dr. A. Fenko September 3th, 2013 Humorous advertisements & motivational values / 2 Humorous advertisements and their effectiveness among customers with different motivational values Judith S. M. Elbers (s0182427) Laaressingel 22-6 7514 ES Enschede E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 06 525 430 25 Study: MSc, Corporate and Organizational Communication Studies MSc, Mental Health Promotion Date: 3 September 2013 Master research Communication Science Supervisors Dr. S. M. Hegner. First supervisor University of Twente Dr. A. Fenko. Second supervisor University of Twente Humorous advertisements & motivational values / 3 Abstract This study examines the effects of different humor tool groups in TV advertisements for customers with different motivational values (Schwartz, 1999). By making use of eighteen different advertisements, the data has been randomly collected by administering questionnaires to students in the Netherlands and in Nepal. After adjusting for control scores, a total of 517 response sets have been used. Results show that humorous advertisements can lead to higher purchase intentions. Considering customers’ motivational values, marketers should keep in mind that customers, who value benevolence, have a less positive attitude towards the advertisement and brand image after they have seen an advertisement containing a humor tool 2 (ludicrousness, irony, understatement); and a less positive attitude towards the brand when they value hedonism and have seen an advertisement containing a humor tool from humor tool group 3 (pun). After re-categorization of the advertisements to the humor categories non-offensive/offensive, the results show that people who value benevolence have a less positive attitude towards the advertisement after seeing an advertisement with non- offensive humor. -

"Weapon of Starvation": the Politics, Propaganda, and Morality of Britain's Hunger Blockade of Germany, 1914-1919

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 2015 A "Weapon of Starvation": The Politics, Propaganda, and Morality of Britain's Hunger Blockade of Germany, 1914-1919 Alyssa Cundy Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Cundy, Alyssa, "A "Weapon of Starvation": The Politics, Propaganda, and Morality of Britain's Hunger Blockade of Germany, 1914-1919" (2015). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1763. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1763 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A “WEAPON OF STARVATION”: THE POLITICS, PROPAGANDA, AND MORALITY OF BRITAIN’S HUNGER BLOCKADE OF GERMANY, 1914-1919 By Alyssa Nicole Cundy Bachelor of Arts (Honours), University of Western Ontario, 2007 Master of Arts, University of Western Ontario, 2008 DISSERTATION Submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Doctor of Philosophy in History Wilfrid Laurier University 2015 Alyssa N. Cundy © 2015 Abstract This dissertation examines the British naval blockade imposed on Imperial Germany between the outbreak of war in August 1914 and the ratification of the Treaty of Versailles in July 1919. The blockade has received modest attention in the historiography of the First World War, despite the assertion in the British official history that extreme privation and hunger resulted in more than 750,000 German civilian deaths. -

Going Native

GoinG native: hSow Marketers are reinventinG the online video advertisinG experience in association with: contents Summary ...............................................................................................................2 Foreword ...............................................................................................................3 Going Native ....................................................................................................... 4 The Changing Face of Distribution .............................................................5 The Power of Video .........................................................................................7 Heineken and 007 .............................................................................................8 Honda Million Mile Joe and Monsters Calling Home ............................ 9 Demand for Native Video .............................................................................10 Using Irreverence to Connect: K-Swiss and Kenny Powers .............. 11 Indie Meets Social Media: The Beauty Inside......................................... 12 The Advantage of Alignment ...................................................................... 13 Matching the Right Content to the Brand: JetBlue .............................14 Conclusion: The Future of the Market ......................................................15 Methodology ......................................................................................................16 summary Marketers are broadly -

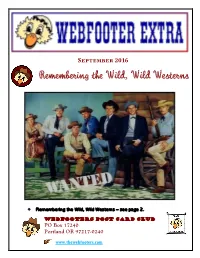

The Webfooter

September 2016 Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns – see page 2. Webfooters Post Card Club PO Box 17240 Portland OR 97217-0240 www.thewebfooters.com Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns Before Batman, before Star Trek and space travel to the moon, Westerns ruled prime time television. Warner Brothers stable of Western stars included (l to r) Will Hutchins – Sugarfoot, Peter Brown – Deputy Johnny McKay in Lawman, Jack Kelly – Bart Maverick, Ty Hardin – Bronco, James Garner – Bret Maverick, Wade Preston – Colt .45, and John Russell – Marshal Dan Troupe in Lawman, circa 1958. Westerns became popular in the early years of television, in the era before television signals were broadcast in color. During the years from 1959 to 1961, thirty-two different Westerns aired in prime time. The television stars that we saw every night were larger than life. In addition to the many western movie stars, many of our heroes and role models were the western television actors like John Russell and Peter Brown of Lawman, Clint Walker on Cheyenne, James Garner on Maverick, James Drury as the Virginian, Chuck Connors as the Rifleman and Steve McQueen of Wanted: Dead or Alive, and the list goes on. Western movies that became popular in the 1940s recalled life in the West in the latter half of the 19th century. They added generous doses of humor and musical fun. As western dramas on radio and television developed, some of them incorporated a combination of cowboy and hillbilly shtick in many western movies and later in TV shows like Gunsmoke. -

The Rockford Files"

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1989 A Social Historical Exploration of the Popularity of "The Rockford Files" Mary Frances Taormina College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, Mass Communication Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Taormina, Mary Frances, "A Social Historical Exploration of the Popularity of "The Rockford Files"" (1989). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625491. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-xjg1-db48 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SOCIAL HISTORICAL EXPLORATION OF THE POPULARITY OF THE ROCKFORD FILES A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the American Studies Program The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Mary Frances Taormina 1989 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, December 1989 Bruce McConachie Chandos Brown Dale Cockerell ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express her appreciation to Professor Bruce McConachie for his patient guidance throughout the preparation of this thesis and his enthusiasm for its subject. The author is also indebted to Professor Chandos Brown for his insights into the subject, and to Professors Brown and Dale Cockerell for their careful reading and criticism of the manuscript.