Archive & Access Formatted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Golden Research Thoughts

GRT Golden ReseaRch ThouGhTs ISSN: 2231-5063 Impact Factor : 4.6052 (UIF) Volume - 6 | Issue - 7 | January – 2017 ___________________________________________________________________________________ RAMANATHAPURAM : PAST AND PRESENT- A BIRD’S EYE VIEW Dr. A. Vadivel Department of History , Presidency College , Chennai , Tamil Nadu. ABSTRACT The present paper is an attempt to focus the physical features, present position and past history of the Ramnad District which was formed in the tail end of the Eighteenth Century. No doubt, the Ramnad District is the oldest district among the districts of the erstwhile Madras Presidency and the present Tamil Nadu. The District was formed by the British with the aim to suppress the southern poligars of the Tamil Country . For a while the southern poligars were rebellious against the expansion of the British hegemony in the south Tamil Country. After the formation of the Madras Presidency , this district became one of its districts. For sometimes it was merged with Madurai District and again its collectorate was formed in 1910. In the independent Tamil Nadu, it was trifurcated into Ramnad, Sivagangai and Viudhunagar districts. The district is, historically, a unique in many ways in the past and present. It was a war-torn region in the Eighteenth Century and famine affected region in the Nineteenth Century, and a region known for the rule of Setupathis. Many freedom fighters emerged in this district and contributed much for the growth of the spirit of nationalism. KEY WORDS : Ramanathapuram, Ramnad, District, Maravas, Setupathi, British Subsidiary System, Doctrine of Lapse ,Dalhousie, Poligars. INTRODUCTION :i Situated in the south east corner of Tamil Nadu State, Ramanathapuram District is highly drought prone and most backward in development. -

Civil Architecture Under Sethupathis

International Multidisciplinary Innovative Research Journal An International refereed e-journal - Arts Issue ISSN: 2456 - 4613 Volume - II (1) September 2017 CIVIL ARCHITECTURE UNDER SETHUPATHIS MALATHI .R Assistant Professor of History V.V.Vanniaperumal College for Women Virudhunagar, Tamil Nadu, India. Architecture is a diverse range of Importance of Forts human activities and the products of those The fort as a center of a city serve a number of activities, usually involving imaginative or purposes from time immemorial. They hold in technical skill[1]. It is the expression or it valuable historical information and provide application of human creative skill and ample scope to enlighten the hidden treasure imagination typically in a visual form of the building culture of Tamil Nadu. Most of producing works to be appreciated primarily the forts were the result of the royal patronage. for their beauty or emotional power. It was thought that building a fort, the king Architecture through the ages has been a would always have protection and peace powerful voice for both secular and religious throughout the country. It might also ensure ideas. Of all the Indian monuments, forts and fame and even immortality. The Tamil rulers, palaces are most fascinating. Most of the their chieftains and officials constructed many Indian forts were built as a defense forts and endowed lavishly for the mechanism to keep the enemy away. The state maintenance of it. The Sethupathis, petty of Rajasthan is home to numerous forts and rulers of small principalities of Ramnad also palaces. In fact, whole India is dotted with contributed their share to the construction of forts of varied sizes. -

Madras Village Survey Monographs, 12, Athangarai, Part VI, Vol-IX

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME IX MADRAS PART VI VILLAGE SURVEY MONOGRAPHS 12. ATHANGARAI P. K. NAMBIAR OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE SUPERINTENDENT OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, MADRAS 1964 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 (Cen!'us Report-Vol. No. IX will relate to Madras only. Under this series will be issued the following publications) Part I-A General Report (2 Volumes) I-B Demography and Vital Statistics * T-C Subsidiary Tables * Part lI-A General Population Tables * II-B (I) General Economic Tables B-1 to B-IV * IT-B (II) B-V to B-IX * ll-C (I) Cultural Tables * IT-C-IT (i) MIgration Tables IJ-C-U (ii) * Part III Household Economic Tables * Part IV-A Report on Honsing and Establishments * IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables" * Part V-A (i) Scheduled Castes and Tribes (ReporL&-Tabb!s SCT I and SCT II) V-A (ii) " (Tables SCT HI to SCT IX and Special Tables) * V-B (I) Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Tribes V-R (II) V-C Todas V-D Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes V-E Ethnographic Notes on Denotified and Nomadic Tribes * Part VI Village Survey Monographs (40 Nos.) * Part VII-A Crafts and Artisans (9 Nos.) VII-B Fairs and Festivals * Part VIII-A Administration Report - Enumeration } For Official use only * VIlI-B Administration Report - Tabulation Part IX Atlas of the Madras State Part X Madras City (2 Volumes) District Census Handbooks on twelve districts Part XI Reports on Special Studies * A Handlooms in Madras State "' B Food Habits in Madras State C Slums of Madras City D Temples of Madras State (5 Volumes) * E Physically Handicapped of Madras State F Family Planning Attitudes: A Survey Part Xl[ Languages of Madras State * ALREADY PUBLISHED FOREWORD Apart from laying the foundations of demography in this sub-continent, a hundred years of the Indian Census has also produced "elaborate and scholarly accounts of the variegated phenomena of Indian life-sometimes with no statistics attached, but usually with just enough statistics to give empirical underpinning to their conclusions". -

I Year Dkh11 : History of Tamilnadu Upto 1967 A.D

M.A. HISTORY - I YEAR DKH11 : HISTORY OF TAMILNADU UPTO 1967 A.D. SYLLABUS Unit - I Introduction : Influence of Geography and Topography on the History of Tamil Nadu - Sources of Tamil Nadu History - Races and Tribes - Pre-history of Tamil Nadu. SangamPeriod : Chronology of the Sangam - Early Pandyas – Administration, Economy, Trade and Commerce - Society - Religion - Art and Architecture. Unit - II The Kalabhras - The Early Pallavas, Origin - First Pandyan Empire - Later PallavasMahendravarma and Narasimhavarman, Pallava’s Administration, Society, Religion, Literature, Art and Architecture. The CholaEmpire : The Imperial Cholas and the Chalukya Cholas, Administration, Society, Education and Literature. Second PandyanEmpire : Political History, Administration, Social Life, Art and Architecture. Unit - III Madurai Sultanate - Tamil Nadu under Vijayanagar Ruler : Administration and Society, Economy, Trade and Commerce, Religion, Art and Architecture - Battle of Talikota 1565 - Kumarakampana’s expedition to Tamil Nadu. Nayakas of Madurai - ViswanathaNayak, MuthuVirappaNayak, TirumalaNayak, Mangammal, Meenakshi. Nayakas of Tanjore :SevappaNayak, RaghunathaNayak, VijayaRaghavaNayak. Nayak of Jingi : VaiyappaTubakiKrishnappa, Krishnappa I, Krishnappa II, Nayak Administration, Life of the people - Culture, Art and Architecture. The Setupatis of Ramanathapuram - Marathas of Tanjore - Ekoji, Serfoji, Tukoji, Serfoji II, Sivaji III - The Europeans in Tamil Nadu. Unit - IV Tamil Nadu under the Nawabs of Arcot - The Carnatic Wars, Administration under the Nawabs - The Mysoreans in Tamil Nadu - The Poligari System - The South Indian Rebellion - The Vellore Mutini- The Land Revenue Administration and Famine Policy - Education under the Company - Growth of Language and Literature in 19th and 20th centuries - Organization of Judiciary - Self Respect Movement. Unit - V Tamil Nadu in Freedom Struggle - Tamil Nadu under Rajaji and Kamaraj - Growth of Education - Anti Hindi & Agitation. -

Report of Public Inq

123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 CHAPTER-I 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 123456 INTRODUCTION 123456 Ramanathapuram District is unique in many respects, particularly for its strategic position, distinct composition, antiquity, role in National movement, controversial Sethu Samudram Project, richness of bio- diversity in Gulf of Mannar, proximity to Ceylon, religious importance and also communal frenzy. Among many significant things, Rameswaram is in this district which is called the “Benarce of South”. This attracts many visitors, tourists and pilgrims. Another significant thing is Rameswaram temple – its beautiful pillared corridor that is the longest in the world. On the structures of the temple Ferguson says this is the specimen of Dravidian style. The earliest inhabitants of the District are Mukkulathore viz., Kallars, Maravars and the Agamudaiyars, Nadars, Chettiars, Yadavas, Dalits and the later additions are Muslims and Christians. The post independent history is dotted with occasional communal tension due to several reasons. A big communal conflagration after the General Election in 1957 in Mudukulathoor and Kamudi regions. The peace talks presided over by the then Collector Mr. Panikar precipitated the matter worse which culminated into the brutal murder of Immanuel Sekaran who fell a martyr of Dalit Liberation. This signaled frequent communal tension in the district. The assertion of the dominant communities, the State’s sanction for it and subsequent developments prompted anti-thesis. Since then every year, on the occasion of Thevar Guru Pooja, a state function and the Guru Pooja of Immanuel Sekaran, the tranquility of the district was marred. Since the issuance of commemorative stamp with the portrait of Immanuel Sekaran by the Government of India and the promise to announce the Guru Pooja of Immanuel Sekaran as State function by AIADMK once it returns to power, the hopes of the Dalits and their conglomeration were ever on the increase. -

The Production of Rurality: Social and Spatial Transformations in the Tamil Countryside 1915-65 by Karthik Rao Cavale Bachelors

The Production of Rurality: Social and Spatial Transformations in the Tamil Countryside 1915-65 By Karthik Rao Cavale Bachelors of Technology (B.Tech) Indian Institute of Technology Madras Masters in City and Regional Planning (M.C.R.P.) Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Urban and Regional Studies at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY February 2020 © 2020 Karthik Rao Cavale. All Rights Reserved The author here by grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Author_________________________________________________________________ Karthik Rao Cavale Department of Urban Studies and Planning December 12, 2019 Certified by _____________________________________________________________ Professor Balakrishnan Rajagopal Department of Urban Studies and Planning Dissertation Supervisor Accepted by_____________________________________________________________ Associate Professor Jinhua Zhao Chair, PhD Committee Department of Urban Studies and Planning 2 The Production of Rurality: Social and Spatial Transformations in the Tamil Countryside 1915-65 by Karthik Rao Cavale Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on December 12, 2019 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Urban and Regional Studies ABSTRACT This dissertation advances a critique of the "planetary urbanization" thesis inspired by Henri Lefebvre’s writings on capitalist urbanization. Theoretically, it argues that Lefebvrian scholars tend to conflate two distinct meanings of urbanization: a) urbanization understood simply as the territorial expansion of certain kinds of built environment associated with commodity production; and b) urbanization as the reproduction of capitalist modes of production of space on an expanded, planetary scale. -

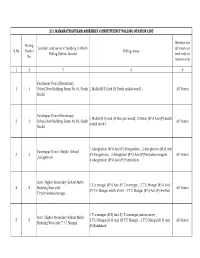

211 Ramanathapuram Assembly Constituency Polling Station List

211 RAMANATHAPURAM ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY POLLING STATION LIST Whether for Polling Location and name of building in which all voters or S.No Station Polling Areas Polling Station located men only or No. women only 12 3 4 5 Panchayat Union Elementary 11School,New Building Room No.01, South 1.Mallal (R.V) And (P) North mallal ward3 , All Voters Mallal Panchayat Union Elementary 1.Mallal (R.V) And (P) Munjan ward2, 2.Mallal (R.V) And (P) South 22School,New Building Room No.02, South All Voters mallal ward3 Mallal 1.Alangkulam (R.V) And (P) Alangkulam , 2.Alangkulam (R.V) And Panchayat Union Middle School 33 (P) Alangkulam , 3.Alangulam (R.V) And (P) Periyakannangudi , All Voters ,Alangkulam 4.Alangkulam (R.V) And (P) Pudukulam Govt. Higher Secondary School,North 1.T.u.mangai (R.V) And (P) T.u.mangai , 2.T.U.Mangai (R.V) And 44Building East side All Voters (P) T.U.Mangai south street , 3.T.U.Mangai (R.V) And (P) Seethai Tiruuthirakosamangai 1.T.u.mangai (R.V) And (P) T.u.mangai yadava street , Govt. Higher Secondary School,North 55 2.T.U.Mangai (R.V) And (P) T.U.Mangai , 3.T.U.Mangai (R.V) And All Voters Buliding West side T. U. Mangai (P) Kalakkudi Whether for Polling Location and name of building in which all voters or S.No Station Polling Areas Polling Station located men only or No. women only 12 3 4 5 1.Vellamarutchikatti (R.V) And (P) Deivasilai nallur , Shanmuga Aided Primary School ,New 2.Vellamarutchikatti (R.V) And (P) Vellamarutchikatti North street 66 All Voters Building South Side Vellamarichikatti , 3.Vellamarutchikatti (R.V) -

A Participatory Study of the Traditional Knowledge of Fishing Communities in the Gulf of Mannar, India

SAMUDRA Monograph A Participatory Study of the Traditional Knowledge of Fishing Communities in the Gulf of Mannar, India The communities of Chinnapalam and Bharathi Nagar Robert Panipilla and Marirajan T International Collective in Support of Fishworkers www.icsf.net SAMUDRA Monograph A Participatory Study of the Traditional Knowledge of Fishing Communities in the Gulf of Mannar, India The communities of Chinnapalam and Bharathi Nagar, Ramanathapuram district, Tamil Nadu, India Robert Panipilla Independent Researcher and Marirajan T Executive Director Peoples Action for Development (PAD) Vembar International Collective in Support of Fishworkers www.icsf.net SAMUDRA Monograph A Participatory Study of the Traditional Knowledge of Fishing Communities in the Gulf of Mannar, India Authors The communities of Chinnapalam and Bharathi Nagar, Ramanathapuram district, Tamil Nadu, India Robert Panipilla, Independent Researcher and Marirajan T, Executive Director Peoples Action for Development (PAD), Vembar October 2014 Edited by KG Kumar and Sumana Narayanan Layout by P Sivasakthivel Front Cover Seaweed collectors of Bharathi Nagar village in the Gulf of Mannar, Ramanathapuram district, Tamil Nadu, India Photo by Shilpi Sharma/ICSF Printed at L S Graphics, Chennai Published by International Collective in Support of Fishworkers 27 College Road, Chennai 600 006, India Tel: +91 44 2827 5303 Fax: +91 44 2825 4457 Email: [email protected] www.icsf.net With support from Bay of Bengal Large Marine Ecosystem (BOBLME) Project Phuket, Thailand Copyright © ICSF 2014 ISBN 978 93 80802 31 2 While ICSF reserves all rights for this publication, any portion of it may be freely copied and distributed, provided appropriate credit is given. Any commercial use of this material is prohibited without prior permission. -

Pamban Rail Bridge – a Historical Perspective

Science Arena Publications Specialty Journal of Humanities and Cultural Science ISSN: 2520-3274 Available online at www.sciarena.com 2019, Vol, 4 (4): 18-23 Pamban Rail Bridge – A Historical Perspective J. Delphine Prema Dhanaseeli PG & Research Department of History, Jayaraj Annapackiam College for Women (Autonomous), Periyakulam-625601, Tamil Nadu, India. Abstract: Bridges are built to span physical obstacles for the purpose of providing way over the obstacle. Pamban Railway Bridge connects Rameswaram town on Pamban Island with mainland India. During 1600– 1800, trade flourished between Pamban, Rameswaram and Sri Lanka by using large boats and small ships. The boat mail was the only train which connected India and Sri Lanka very closer. The Pamban Railway Bridge was opened to traffic on 24 February 1914 and it was the only link to Rameswaram till 1987. Though the cyclone of 1964 destroyed the bridge, within very short period the railway engineers renovated the bridge and continued the service. This paper makes an attempt to highlight the features of hundred year old historical Pamban Rail Bridge. Keywords: Pamban, Cantilever bridge, Rameswaram, Sri Lanka, Boat mail. INTRODUCTION The Pamban rail bridge is the India’s first cantilever bridge, connecting Rameswaram with the mainland India. It is the India’s first sea bridge constructed in Tamil Nadu. The mainland end of the bridge is located at 9º16´56.70´N 79º11´20.1212”E to 9.2824167ºN 79.188922556ºE. This 2.06 km long Pamban Bridge is the second longest sea bridge in India after Bandra-worli sea link. It was constructed in a special manner to allow ships to pass under the bridge (Francis et al., 1988). -

9781503628663.Pdf

PROTESTANT TEXTUALITY AND THE TAMIL MODERN SOUTH ASIA IN MOTION EDITOR Thomas Blom Hansen EDITORIAL BOARD Sanjib Baruah Anne Blackburn Satish Deshpande Faisal Devji Christophe Jaffrelot Naveeda Khan Stacey Leigh Pigg Mrinalini Sinha Ravi Vasudevan PROTESTANT TEXTUALITY AND THE TAMIL MODERN Political Oratory and the Social Imaginary in South Asia BERNARD BATE Edited by E. Annamalai, Francis Cody, Malarvizhi Jayanth, and Constantine V. Nakassis STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Stanford, California Stanford University Press Stanford, California This book has been published with assistance from the Committee on Southern Asian Studies at the University of Chicago. © 2021 by the Estate of Bernard Bate. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 license. To view a copy of the license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Suggested citation: Bate, Bernard. Protestant Textuality and the Tamil Modern: Political Oratory and the Social Imaginary in South Asia. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2021. doi: http://doi.org/10.21627/9781503628663. Chapter 1: Originally published in Pandian, Anand, and Daud Ali, eds. Ethical Life in South Asia, pp. 101–15 © 2010 Indiana University Press. Used by permission, all rights reserved. Chapter 2: Originally published in The Indian Economic and Social History Review, Vol. 42, Issue 4 © 2005. The Indian Economic and Social History Association. All rights reserved. Reproduced with the permission of the copyright holders and the publishers, SAGE PublicaFons India Pvt. Ltd, New Delhi. Epilogue: Originally published in Comparative Studies in Society and History, 55(1), pp. 142-166, © 2013. Cambridge University Press. Used by permission, all rights reserved. -

History of Pudukottai District a Study [1] P

ISSN (Online) 2456 -1304 International Journal of Science, Engineering and Management (IJSEM) Vol 3, Issue 4, April 2018 History of Pudukottai District a Study [1] P. Manikandan [1] Ph.D.Research Scholar,P.G. and Research Department of History,V.O. Chidambaram College,Thoothukudi. Abstract:- Pudukottai became a separate district only during recent times. The area is clearly founded upon ancient traditions. The district of Pudukottai has a very eminent history. It seems to have seen the ruling of various dynasties over the course of time. Our Tamil literature has seen various poets who have hailed from this particular area. It proves to be a very sacred land to the Pandyas. It was a great centre of trade and business. History tells that many of the wars between the Pallavas and the Pandiyas have been fought in this area. Tamil literature of the Sangam period has mentioned many places of this district. The district became a sort of marchar land between the Pandyas and the Pallavas. The Cauveri river plays an important role in the geography of the area. The area is a reserve for various archaeological explorations. It has many monuments and scriptures that identify the diversity of rulers the land has seen. It is a abode of cultural inferences. The ground has always been a point for power struggle between the Cholas, Pandiyas and the Pallavas. The area was at its beneficial peak only during the reign of Raja Raja I. In the 17th and 18th centuries the area also saw the rule of the Thondaiman Dynasty. The famous Carnatic Wars were mostly fought around Tiruchirapalli. -

Annual Activity Report 2015-16

RWDS Annual Activity Report 2015-16 RURAL WORKERS DEVELOPMENT SOCIETY 2/1751, Om Sakthi Nagar 13th Street, Ramanathapuram – 623 503 Phone:04567230435 [email protected] 1 RURAL WORKERS DEVELOPMENT SOCIETY (RWDS) RAMANATHAPURAM - 623503 ANNUAL ACTIVITY REPORT FOR APRIL 2015 –MARCH 2016 Introduction: Rural Workers Development Society was founded in the year 2007 by a group of public minded leaders those who are effectively concerning in community development activities for more than three decades. It was registered under Tamilnadu Societies Registration Act vide Registration number 93/2007. Its head quarters are located in Ramanathapuram. RWDS is working among children, women, youth, farmers, rural unorganized workers especially Palmyrah Workers in Ramnad District. Target Area: State : Tamilnadu District : Ramanathapuram, Sivagangai, Tuticorin Blocks : Ramanathapuram, Kadalady, Tirupullani, Mandapam, Paramakudi, Tiruvadanai, Bogalur, Villathikulam and Devakottai. Vision: The socio economic development of the marginalized with emphasis on Palmyrah Workers, Women and Children 2 Mission: To mobilize and federate the Palmyrah workers irrespective of caste, creed or religion to organize for their livelihood issues. To make them understand their condition and motivate them to participate in their development through awareness generation. To improve their bargaining power and to link with Govt and formal institutions for self reliance and substances. To enable for adequate health and education to Children for better tomorrow. Working Areas: Ramanathapuram is situated along the Eastern coastal District of the Southern Tamilnad. The Bay of Bengal in the east, The Calf of manner in the whole sea shore, Sivagangai, Pudukottai, Virudhunagar,and Tuticorin constitute it boundaries. Spreading over an area of 4232 sq’km.