Madras Village Survey Monographs, 12, Athangarai, Part VI, Vol-IX

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Academic Calendar 19-20

Academic Calendar 2019-20 TBAK COLLEGE FOR WOMEN THASSIM BEEVI ABDUL KADER COLLEGE FOR WOMEN Kilakarai - 623 517, Ramanathapuram District Sponsored by Seethakathi Trust, Chennai - 600 006 [A Minority Autonomous Institution & Re-accredited by NAAC with B++ Grade ISO 9001:2015 Certified Institution] Affiliated to Alagappa University, Karaikudi 2 0 1 9 - 2 0 1 TBAK COLLEGE FOR WOMEN Academic Calendar 2019-20 In the name of the Almighty, The Most Gracious, The Most Merciful! All praise be to the Almighty only! Towards the end of the meeting recite this together with the audience Glory be to the Almighty and praise be to Him! Glory be to YOU and all praise be to You! I bear witness that there is no true GOD except YOU alone. I ask your pardon and turn to YOU in repentance. [Dua from the Hadith of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) Narrated by Abu Hurairah (Rali) Source: Abu Dawud: 4859] 2 Academic Calendar 2019-20 TBAK COLLEGE FOR WOMEN In the Name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful Proclaim (Or Read :) In the name of thy Lord and Cherisher, Who Created man, out of a mere clot of congealed blood. Proclaim! And thy Lord is Most Bountiful He who taught the use of the pen Taught man that which he knew not Nay, but man doth transgress all bounds In that he looketh upon himself as self-sufficient. Verily, to thy Lord is the return of all. Alquran Sura 96: (verses 1 to 8) 3 TBAK COLLEGE FOR WOMEN Academic Calendar 2019-20 Founded in 1988 G O No 1448 dated 12 September 1988 THASSIM BEEVI ABDUL KADER COLLEGE FOR WOMEN (Sponsored by Seethakathi Trust, Chennai) (Affiliated to Alagappa University, Karaikudi) No. -

ANSWERED ON:11.05.2005 AUTOMATIC and MODERN TELEPHONE EXCHANGES in TAMIL NADU Kharventhan Shri Salarapatty Kuppusamy

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA COMMUNICATIONS AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:6879 ANSWERED ON:11.05.2005 AUTOMATIC AND MODERN TELEPHONE EXCHANGES IN TAMIL NADU Kharventhan Shri Salarapatty Kuppusamy Will the Minister of COMMUNICATIONS AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY be pleased to state: (a) the details of automatic and modern telephone exchanges set up in Tamil Nadu during the last three years, location- wise; (b) the details of such exchanges proposed to be set up in Tamil Nadu during the current year; (c) the details of the telephone exchanges whose capacities were expanded in the current financial year; and (d) the details of telephone exchanges where waiting list for telephone connection still exists? Answer THE MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF COMMUNICATIONS ANDINFORMATION TECHNOLOGY (DR. SHAKEEL AHMAD) (a) The details of automatic and modern telephone exchanges set up in Tamilnadu during the last three years are given in the Annexures- I(a), I(b) & I(c). (b) The details of such exchanges proposed to be set up in Tamilnadu during the current year are given in Annexure-II. (c) The details of the telephone exchanges whose capacities were expanded in the current financial year are given at Annexure-III. (d) The details of telephone exchanges where waiting list for telephone connection still exists are given in Annexure- IV. ANNEXURE-I(a) DETAILS OF TELEPHONE EXCHANGES SET UP DURING 2002-03 IN TAMILNADU Sl Name of Exchange Capacity Type/Technology District No.(Location) 1 Avinashi-II 4000 CDOTMBMXL Coimbatore 2 K.P.Pudur -

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K. Pandeeswaran No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Intercaste Marriage certificate not enclosed Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 2 AP-2 P. Karthigai Selvi No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Only one ID proof attached. Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 3 AP-8 N. Esakkiappan No.37/45E, Nandhagopalapuram, Above age Thoothukudi – 628 002. 4 AP-25 M. Dinesh No.4/133, Kothamalai Road,Vadaku Only one ID proof attached. Street,Vadugam Post,Rasipuram Taluk, Namakkal – 637 407. 5 AP-26 K. Venkatesh No.4/47, Kettupatti, Only one ID proof attached. Dokkupodhanahalli, Dharmapuri – 636 807. 6 AP-28 P. Manipandi 1stStreet, 24thWard, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Sivaji Nagar, and photo Theni – 625 531. 7 AP-49 K. Sobanbabu No.10/4, T.K.Garden, 3rdStreet, Korukkupet, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Chennai – 600 021. and photo 8 AP-58 S. Barkavi No.168, Sivaji Nagar, Veerampattinam, Community Certificate Wrongly enclosed Pondicherry – 605 007. 9 AP-60 V.A.Kishor Kumar No.19, Thilagar nagar, Ist st, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Chennai -600 019 10 AP-61 D.Anbalagan No.8/171, Church Street, Only one ID proof attached. Komathimuthupuram Post, Panaiyoor(via) Changarankovil Taluk, Tirunelveli, 627 761. 11 AP-64 S. Arun kannan No. 15D, Poonga Nagar, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Ch – 600 019 12 AP-69 K. Lavanya Priyadharshini No, 35, A Block, Nochi Nagar, Mylapore, Only one ID proof attached. Chennai – 600 004 13 AP-70 G. -

Ramanathapuram-2020

RAMANATHAPURAM-2020 CONTACT NUMBERS OFFICE OF THE STATE LEVEL REVENUE OFFICERS CHENNAI Additional Chief Secretary to Government, Phone - 044 -25671556 Revenue Department Chennai Fax-044-24918098 Additional Chief Secretary Phone -044-28410577 Commissioner of Revenue Administration, Fax-044-28410540 Chennai Commissioner Phone-044-28544249 (Disaster Management and Mitigation) Fax-044-28420207 DISTRICT COLLECTORATE RAMANATHAPURAM Collector, 04567- 231220, 221349 9444183000 Ramanathapuram Fax : 04567 – 220648 Fax (Off) : 04567 – 230558 District Revenue officer 04567 - 230640, 230610 9445000926 Ramanathapuram Personal Assistant (General) 04567- 230056 9445008147 to Collector , 04567 - 230057 Ramanathapuram 04567 - 230058 04567 - 230059 DISTRICT EMERGENCY OPERATION CENTER Disaster Management Toll Free No : 04567-1077 : 04567 -230092 INDIAN METEOROLOGICAL DEPARTMENT Deputy Director General 044 – 28276752 Director 044 – 28229860 Director (Seismic Section) 044 – 28277061 Control Room 044–28271951/28230091 28230092/ 28230094 COLLECTORATE RAMANATHAPURAM 04567 - 231220, 221349 1 District Collector, Thiru. K Veera Raghava Fax: 04567 220648 9444183000 Ramanathapuram Rao,I.A.S., Fax (Off): 04567 - 230558 District Revenue Officer, Tmt.A.Sivagami,M.sc,MCA., 04567-230558, 2 Ramanathapuram 230640 9445000926 Additional Collector(Dev) , Thiru.M.Pradeep Kumar 3 04567-230630 7373704225 DRDA, Ramanathapuram I.A.S., Personal Assistant Thiru.G.Gopu (i/c) 04567 - 230056 9445008147 5 (General ) to Collector 230057, 230058 Ramanathapuram 04567 - 230059 6379818243 Assistant Director Thiru.Kesava Dhasan 04567 –230431 7402608158 7 (Panchayats), Ramanathapuram. 9894141393 Revenue Divisional Thiru. N,Sugaputhira,I.A.S., 8 04567 - 220330 9445000472 Officer, Ramanathapuram Revenue Divisional Thiru.S.Thangavel 9 04564-224151 9445000473 Officer,, Paramakudi District AdiDravidarand Thiru.G.Gopu 13 Tribal Welfare officer, 04567-232101 7338801269 Ramanathapuram District Backwardclass Thiru .Manimaran 9443647321 14 welfare officer , 04567-231288 Ramanathapuram District Inspection Cell 04567-230056 15 C. -

Golden Research Thoughts

GRT Golden ReseaRch ThouGhTs ISSN: 2231-5063 Impact Factor : 4.6052 (UIF) Volume - 6 | Issue - 7 | January – 2017 ___________________________________________________________________________________ RAMANATHAPURAM : PAST AND PRESENT- A BIRD’S EYE VIEW Dr. A. Vadivel Department of History , Presidency College , Chennai , Tamil Nadu. ABSTRACT The present paper is an attempt to focus the physical features, present position and past history of the Ramnad District which was formed in the tail end of the Eighteenth Century. No doubt, the Ramnad District is the oldest district among the districts of the erstwhile Madras Presidency and the present Tamil Nadu. The District was formed by the British with the aim to suppress the southern poligars of the Tamil Country . For a while the southern poligars were rebellious against the expansion of the British hegemony in the south Tamil Country. After the formation of the Madras Presidency , this district became one of its districts. For sometimes it was merged with Madurai District and again its collectorate was formed in 1910. In the independent Tamil Nadu, it was trifurcated into Ramnad, Sivagangai and Viudhunagar districts. The district is, historically, a unique in many ways in the past and present. It was a war-torn region in the Eighteenth Century and famine affected region in the Nineteenth Century, and a region known for the rule of Setupathis. Many freedom fighters emerged in this district and contributed much for the growth of the spirit of nationalism. KEY WORDS : Ramanathapuram, Ramnad, District, Maravas, Setupathi, British Subsidiary System, Doctrine of Lapse ,Dalhousie, Poligars. INTRODUCTION :i Situated in the south east corner of Tamil Nadu State, Ramanathapuram District is highly drought prone and most backward in development. -

Civil Architecture Under Sethupathis

International Multidisciplinary Innovative Research Journal An International refereed e-journal - Arts Issue ISSN: 2456 - 4613 Volume - II (1) September 2017 CIVIL ARCHITECTURE UNDER SETHUPATHIS MALATHI .R Assistant Professor of History V.V.Vanniaperumal College for Women Virudhunagar, Tamil Nadu, India. Architecture is a diverse range of Importance of Forts human activities and the products of those The fort as a center of a city serve a number of activities, usually involving imaginative or purposes from time immemorial. They hold in technical skill[1]. It is the expression or it valuable historical information and provide application of human creative skill and ample scope to enlighten the hidden treasure imagination typically in a visual form of the building culture of Tamil Nadu. Most of producing works to be appreciated primarily the forts were the result of the royal patronage. for their beauty or emotional power. It was thought that building a fort, the king Architecture through the ages has been a would always have protection and peace powerful voice for both secular and religious throughout the country. It might also ensure ideas. Of all the Indian monuments, forts and fame and even immortality. The Tamil rulers, palaces are most fascinating. Most of the their chieftains and officials constructed many Indian forts were built as a defense forts and endowed lavishly for the mechanism to keep the enemy away. The state maintenance of it. The Sethupathis, petty of Rajasthan is home to numerous forts and rulers of small principalities of Ramnad also palaces. In fact, whole India is dotted with contributed their share to the construction of forts of varied sizes. -

Community-Supported Management and Conservation Strategies for Seagrass Beds in Palk Bay

1 Community-supported management and conservation strategies for seagrass beds in Palk Bay Clown fish amongst the seagrass of Palk bay © SDMRI Final Project Report December 2014 – January 2016 IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature India Country Office Project Details Community-supported management and conservation strategies Project Name for seagrass beds in Palk Bay IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature Grantee Name & Address India Country Office C4/25 Safdarjung Development Area, New Delhi, 110016, India Principle Investigator: Ms. Nisha D’Souza, IUCN India Country Office Project Associate: Ms. Jagriti Kumari, IUCN India Country Office Implementing partner: Suganti Devadason Marine Research Institute (SDMRI) Advisors: Dr. NM Ishwar (Programme Coordinator, IUCN India Project team Country Office); Dr. Saudamini Das (Associate Professor, Institute of Economic Growth); Dr. RC Bhatta (Professor of Fisheries Economics, College of Fisheries); Dr. Ruchi Badola (Scientist- G/Senior Professor, Wildlife Institute of India); Dr. E. Vivekananda (Scientist Emeritus, Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute); Dr. JD Sophia (Principal Scientist, M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation); Dr. Y. Yadava (Director, Bay of Bengal Programme, Inter-Governmental Organization) Project Start Date 12 December 2014 Project End Date 11 January 2016 Reporting Period Final report Submitted to GIZ on: 12 February 2016 Produced with the financial support of GIZ. 2 Contents page Contents Page No. 1. Background to the Project 4 2. Summary of Project Activities 5 3. Literature Review 3.1 Palk Bay Marine Ecosystem 6 3.2 Linkages Between Seagrass and Fisheries 8 3.3 Economic Valuation of Seagrass 9 3.4 Management & Conservation of Palk Bay seagrass 11 3.5 Participatory Management 12 4. -

I Year Dkh11 : History of Tamilnadu Upto 1967 A.D

M.A. HISTORY - I YEAR DKH11 : HISTORY OF TAMILNADU UPTO 1967 A.D. SYLLABUS Unit - I Introduction : Influence of Geography and Topography on the History of Tamil Nadu - Sources of Tamil Nadu History - Races and Tribes - Pre-history of Tamil Nadu. SangamPeriod : Chronology of the Sangam - Early Pandyas – Administration, Economy, Trade and Commerce - Society - Religion - Art and Architecture. Unit - II The Kalabhras - The Early Pallavas, Origin - First Pandyan Empire - Later PallavasMahendravarma and Narasimhavarman, Pallava’s Administration, Society, Religion, Literature, Art and Architecture. The CholaEmpire : The Imperial Cholas and the Chalukya Cholas, Administration, Society, Education and Literature. Second PandyanEmpire : Political History, Administration, Social Life, Art and Architecture. Unit - III Madurai Sultanate - Tamil Nadu under Vijayanagar Ruler : Administration and Society, Economy, Trade and Commerce, Religion, Art and Architecture - Battle of Talikota 1565 - Kumarakampana’s expedition to Tamil Nadu. Nayakas of Madurai - ViswanathaNayak, MuthuVirappaNayak, TirumalaNayak, Mangammal, Meenakshi. Nayakas of Tanjore :SevappaNayak, RaghunathaNayak, VijayaRaghavaNayak. Nayak of Jingi : VaiyappaTubakiKrishnappa, Krishnappa I, Krishnappa II, Nayak Administration, Life of the people - Culture, Art and Architecture. The Setupatis of Ramanathapuram - Marathas of Tanjore - Ekoji, Serfoji, Tukoji, Serfoji II, Sivaji III - The Europeans in Tamil Nadu. Unit - IV Tamil Nadu under the Nawabs of Arcot - The Carnatic Wars, Administration under the Nawabs - The Mysoreans in Tamil Nadu - The Poligari System - The South Indian Rebellion - The Vellore Mutini- The Land Revenue Administration and Famine Policy - Education under the Company - Growth of Language and Literature in 19th and 20th centuries - Organization of Judiciary - Self Respect Movement. Unit - V Tamil Nadu in Freedom Struggle - Tamil Nadu under Rajaji and Kamaraj - Growth of Education - Anti Hindi & Agitation. -

LIST of KUDIMARAMATH WORKS 2019-20 WATER BODIES RESTORATION with PARTICIPATORY APPROACH Annexure to G.O(Ms)No.58, Public Works (W2) Department, Dated 13.06.2019

GOVERNMENT OF TAMILNADU PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT WATER RESOURCES ORGANISATION ANNEXURE TO G.O(Ms.)NO. 58 PUBLIC WORKS (W2) DEPARTMENT, DATED 13.06.2019 LIST OF KUDIMARAMATH WORKS 2019-20 WATER BODIES RESTORATION WITH PARTICIPATORY APPROACH Annexure to G.O(Ms)No.58, Public Works (W2) Department, Dated 13.06.2019 Kudimaramath Scheme 2019-20 Water Bodies Restoration with Participatory Approach General Abstract Total Amount Sl.No Region No.of Works Page No (Rs. In Lakhs) 1 Chennai 277 9300.00 1 - 26 2 Trichy 543 10988.40 27 - 82 3 Madurai 681 23000.00 83 - 132 4 Coimbatore 328 6680.40 133 - 181 Total 1829 49968.80 KUDIMARAMATH SCHEME 2019-2020 CHENNAI REGION - ABSTRACT Estimate Sl. Amount No Name of District No. of Works Rs. in Lakhs 1 Thiruvallur 30 1017.00 2 Kancheepuram 38 1522.00 3 Dharmapuri 10 497.00 4 Tiruvannamalai 37 1607.00 5 Villupuram 73 2642.00 6 Cuddalore 36 815.00 7 Vellore 53 1200.00 Total 277 9300.00 1 KUDIMARAMATH SCHEME 2019-2020 CHENNAI REGION Estimate Sl. District Amount Ayacut Tank Unique No wise Name of work Constituency Rs. in Lakhs (in Ha) Code Sl.No. THIRUVALLUR DISTRICT Restoration by Removal of shoals and Reconstruction of sluice 1 1 and desilting the supply channel in Neidavoyal Periya eri Tank in 28.00 Ponneri 354.51 TNCH-02-T0210 ponneri Taluk of Thiruvallur District Restoration by Removal of shoals and Reconstruction of sluice 2 2 and desilting the supply channel in Voyalur Mamanikkal Tank in 44.00 Ponneri 386.89 TNCH-02-T0187 ponneri Taluk of Thiruvallur District Restoration by Removal of shoals and Reconstruction -

E960 Public Disclosure Authorized

Health care Waste Management System E960 Public Disclosure Authorized TNHSDP Public Disclosure Authorized Health Care Waste Management System Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Health care Waste Management System Health Care Waste Management System The Government of Tamil Nadu has proposed to implement a Health Systems Development Project (HSDP) with the World Bank assistance. The main objective of the HSDP is to improve the health outcomes of the people of Tamil Nadu with special reference to poor especially in remote and inaccessible areas. The project objectives are in keeping with the Millennium Development Goals. The HSDP envisages a substantial improvement in health infrastructure at the secondary level institutions. Several interventions have been planned for reducing infant, child and maternal mortality and morbidity. The project would also develop effective models to combat non communicable diseases like diabetes, hypertension, cardio vascular diseases, cancer etc. HSDP also plans to develop a comprehensive Health Management Information System in addition to capacity building of the health functionaries. The project would attempt to initiate bring a fruitful Public Private Partnership in health sector. The Govt. of Tamil Nadu has analysed the present scenario of bio medical waste management right from tertiary institutions to the PHCs. The Bio Medical waste management in private sector has also been analysed. The bio medical waste generated by the health institutions both in public and private sector needs to be regulated under the Bio-Medical Waste (Management and Handling) (Second Amendment) Rules 2000, Ministry of Environment and Forest, Govt. of India Notification New Delhi. Under the health care waste management plan Govt. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2012 [Price: Rs. 28.80 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 37] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 19, 2012 Purattasi 3, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2043 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Change of Names .. 2325-2395 Notices .. 2240-2242 .. 1764 1541-1617 NoticeNOTICE .. 1617 NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES 34603. My daughter, N. Rizwana, born on 12th November 34606. I, B. Vel, son of Thiru K. Bethuraj, born on 4th April 1996 (native district: Ramanathapuram), residing at 1967 (native district: Theni), residing at No. 63-NA, Vaigai No. 11-7B/68, New Ramnad Road, Visalam, Madurai- Colony, Anna Nagar, Madurai-625 020, shall henceforth be 625 009, shall henceforth be known as N. RISVANA BEGAM. known as B. VELUCHAMY. ï£Ã˜H„¬ê. B. VEL. Madurai, 10th September 2012. (Father.) Madurai, 10th September 2012. 34604. I, N. Radha, daughter of Thiru V. Navaneethan, 34607. I, N. Thirupathi, son of Thiru Narayanasamy, born born on 18th July 1991 (native district: Calcutta-West Bengal), on 7th June 1983 (native district: Dindigul), residing at residing at No. 1/65A, Katchaikatti, T. Vadipatti Taluk, Madurai-625 218, shall henceforth be known No. 1C, Melaponnakaram 2nd Street, Arapalayam Post, as N. -

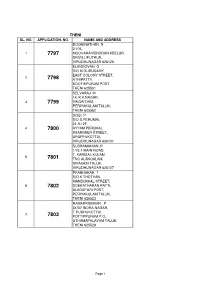

THENI APP.Pdf

THENI SL. NO. APPLICATION. NO. NAME AND ADDRESS BOOMINATHAN. R 2/105, 1 7797 MOOVARAIVENDRAN KEELUR, SRIVILLIPUTHUR, VIRUDHUNAGAR 626125 ELANGOVAN. G S/O M.GURUSAMY EAST COLONY STREET, 2 7798 ATHIPATTY, BOOTHIPURAM POST, THENI 625531 SELVARAJ. M 14, K.K.NAGAR, 3 7799 VAIGAI DAM, PERIYAKULAM TALUK, THENI 625562 GOBI. P S/O S.PERUMAL 21-9-12F, 4 7800 AYYAM PERUMAL ASARIMIER STREET, ARUPPUKOTTAI, VIRUDHUNAGAR 626101 SUBRAMANIAN .P 1/73-1 MAIN ROAD, T. KARISAL KULAM, 5 7801 TNC ALANGALAM, SIVAKASI TALUK, VIRUDHUNAGAR 626127 PRABHAKAR. T S/O K.THOTHAN MANDUKKAL STREET, 6 7802 SOKKATHARAN PATTI, ALAGAPURI POST, PERIYAKULAM TALUK, THENI 626523 RAMAKRISHNAN . P 31/B7 INDRA NAGAR, T.PUDHUKOTTAI, 7 7803 POTTIPPURAM P.O, UTHAMAPALAYAM TALUK, THENI 625528 Page 1 BASKARAN. G 2/1714. OM SANTHI NAGAR, 11TH STREET, 8 7804 ARANMANAI SALI, COLLECTRATE POST, RAMNAD 623503 SURESHKUMAR.S 119, LAKSHMIAPURAM, 9 7805 INAM KARISAL KULAM (POST), SRIVILLIPUTTUR, VIRUTHU NAGAR 626125 VIJAYASANTHI. R D/O P.RAJ 166, NORTH STREET, 10 7806 UPPUKKOTTAI, BODI TK, THENI 625534 RAMJI.A S/O P.AYYAR 5/107, NEHRUNAGAR, 11 7807 E-PUTHUKOTTAI, MURUGAMALAI NAGAR (PO), PERIYAKULAM (TK), THENI 625605 KRISHNASAMY. M 195/31, 12 7808 GANDHIPURAM STREET, VIRUDHUNAGAR 626001 SIVANESAN. M 6/585-3A, MSSM ILLAM, 13 7809 3RD CROSS STREET, LAKSHMI NAGAR, VIRUDHUNAGAR 626001 GIRI. G S/O GOVINDARAJ. I 69, NORTH KARISALKULAM, 14 7810 INAM KARISAL KULAM POST, SRIVILLIPUTTUR TALUK, VIRUDHUNAGAR 626125 PARTHASARATHY. V S/O VELUSAMY 2-3, TNH,BVANNIAMPATTY, 15 7811 VILLAKKUINAM, KARISALKULAM POST, SRIVILLIPUTHUR TALUK, VIRUDHUNAGAR 626125 Page 2 MAHARAJA.S 11, WEST STREET, MANICKPURAM, 16 7812 KAMARAJAPURAM (PO), BODI (TK), THENI 625682 PALANICHAMY.