Ohlsson Plays Brahms Saturday, May 2Nd, 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940 Academic attention has focused on America’sinfluence on European stage works, and yet dozens of operettas from Austria and Germany were produced on Broadway and in the West End, and their impact on the musical life of the early twentieth century is undeniable. In this ground-breaking book, Derek B. Scott examines the cultural transfer of operetta from the German stage to Britain and the USA and offers a historical and critical survey of these operettas and their music. In the period 1900–1940, over sixty operettas were produced in the West End, and over seventy on Broadway. A study of these stage works is important for the light they shine on a variety of social topics of the period – from modernity and gender relations to new technology and new media – and these are investigated in the individual chapters. This book is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306. derek b. scott is Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds. -

Operetta After the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen a Dissertation

Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Elaine Tennant Spring 2013 © 2013 Ulrike Petersen All Rights Reserved Abstract Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair This thesis discusses the political, social, and cultural impact of operetta in Vienna after the collapse of the Habsburg Empire. As an alternative to the prevailing literature, which has approached this form of musical theater mostly through broad surveys and detailed studies of a handful of well‐known masterpieces, my dissertation presents a montage of loosely connected, previously unconsidered case studies. Each chapter examines one or two highly significant, but radically unfamiliar, moments in the history of operetta during Austria’s five successive political eras in the first half of the twentieth century. Exploring operetta’s importance for the image of Vienna, these vignettes aim to supply new glimpses not only of a seemingly obsolete art form but also of the urban and cultural life of which it was a part. My stories evolve around the following works: Der Millionenonkel (1913), Austria’s first feature‐length motion picture, a collage of the most successful stage roles of a celebrated -

Poetik Und Dramaturgie Der Komischen Operette

9 Romanische Literaturen und Kulturen Albert Gier ‚ Wär es auch nichts als ein Augenblick Poetik und Dramaturgie der komischen Operette ‘ 9 Romanische Literaturen und Kulturen Romanische Literaturen und Kulturen hrsg. von Dina De Rentiies, Albert Gier und Enrique Rodrigues-Moura Band 9 2014 ‚ Wär es auch nichts als ein Augenblick Poetik und Dramaturgie der komischen Operette Albert Gier 2014 Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deut- schen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Informationen sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de/ abrufbar. Dieses Werk ist als freie Onlineversion über den Hochschulschriften-Server (OPUS; http://www.opus-bayern.de/uni-bamberg/) der Universitätsbibliothek Bamberg erreichbar. Kopien und Ausdrucke dürfen nur zum privaten und sons- tigen eigenen Gebrauch angefertigt werden. Herstellung und Druck: Digital Print Group, Nürnberg Umschlaggestaltung: University of Bamberg Press Titelbild: Johann Strauß, Die Fledermaus, Regie Christof Loy, Bühnenbild und Kostüme Herbert Murauer, Oper Frankfurt (2011). Bild Monika Rittershaus. Abdruck mit freundlicher Genehmigung von Monika Rittershaus (Berlin). © University of Bamberg Press Bamberg 2014 http://www.uni-bamberg.de/ubp/ ISSN: 1867-5042 ISBN: 978-3-86309-258-0 (Druckausgabe) eISBN: 978-3-86309-259-7 (Online-Ausgabe) URN: urn:nbn:de:bvb:473-opus4-106760 Inhalt Einleitung 7 Kapitel I: Eine Gattung wird besichtigt 17 Eigentlichkeit 18; Uneigentliche Eigentlichkeit -

The Merry Widow and the Belle Époque 2015/16 8 Historical and Cultural Timeline

Contents 3 PREPARING FOR THE PERFORMANCE 4 SYNOPSIS OF THE OPERA 6 LA VIE PARISIENNE—THE MERRY WIDOW AND THE BELLE ÉPOQUE 2015/16 8 HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL TIMELINE 13 REFLECTING ON THE PERFORMANCE Online Resources TheBy Franz Lehár Merry Widow MUSICAL HIGHLIGHTS COMPOSER AND LIBRETTIST BIOGRAPHIES OPERA TERMINOLOGY PERFORMANCE ETIQUETTE < Lyric Unlimited is Lyric Opera of Chicago’s department dedicated to education, community engagement, and new artistic initiatives. Major support provided by the Nancy W. Knowles Student and Family Performances Fund. Performances for Students are supported by an Anonymous Donor, Baird, the John W. and Rosemary K. Brown Family Foundation, Bulley & Andrews LLC, The Jacob and Rosalie Cohn Foundation, the Dan J. Epstein Family Foundation, the General Mills Foundation, John Hart and Carol Prins, the Dr. Scholl Foundation, the Segal Family Foundation, the Bill and Orli Staley Foundation, the Donna Van Eekeren Foundation, Mrs. Roy I. Warshawsky, and Michael Welsh and Linda Brummer. Lyric Unlimited was launched with major catalyst funding from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and receives major support from the Hurvis Family Foundation. Written by: Jesse Gram, Cate Mascari, Maia Morgan, Roger Photo: Ken Howard (Metropolitan Opera) Pines, and Todd Snead Lyric Opera presentation of Lehár’s The Merry Widow generously made possible by the Donna Van Eekeren Foundation, Howard Gottlieb and Barbara Greis, Mr. J. Thomas Hurvis, Kirkland & Ellis LLP, and the Mazza Foundation. Production owned by The Metropolitan Opera. Dear Educator, Welcome to the latest edition of Lyric Unlimited’s Backstage Pass! This is your ticket to the world of opera and your insider’s guide to Lyric’s production of The Merry Widow. -

Die Lustige Witwe the Merry Widow Page 1 of 3 Opera Assn

San Francisco War Memorial 1981 Die Lustige Witwe The Merry Widow Page 1 of 3 Opera Assn. Opera House Die Lustige Witwe (in English) Opera in three acts by Franz Lehár Libretto by Victor Léon and Leo Stein Based on Henri Meilhac's comedy "L'Attaché" Conductor CAST Richard Bonynge Baron Mirko Zeta, Pontevedrian ambassador in Paris Phil Stark Stage Director Valencienne, his wife Judith Forst Lotfi Mansouri Camille de Rosillon, a Parisian gentleman Anson Austin † Set Designer Vicomte Cascada, a Latin diplomat Jonathan Green Murray Laufer Raoul de St. Brioche, a French diplomat Thomas Woodman Costume Designer Kromow, Pontevedrian military councillor Stanley Wexler Suzanne Mess Olga, his wife Phyllis Hunter Lighting Designer Pritschitsch, Pontevedrian consul Gary Harger Joan Sullivan Praskowia, his wife Ingrid Olsson Choreographer Bogdanowitsch, Pontevedrian military attaché John Del Carlo Christian Holder Silviane, his wife Sara Ganz Sound Designer Njegus, an embassy secretary Gerald Isaac Roger Gans Anna Glawari, the merry widow Joan Sutherland Chorus Director Danilo Danilowitch, first secretary to Baron Zeta Håkan Hagegård Richard Bradshaw Maître d'hôtel at Maxim's Abe Kalish Musical Preparation Zozo Nancy Bleiweiss Kathryn Cathcart Grisette Peggy Davis Prompter Anne Elizabeth Egan Gordon Jephtas Carolyn Houser Assistant Stage Director Marti Kennedy Anne Catherine Ewers Kathryn Roszak Stage Manager Katherine Warner Gretchen Mueller Solo dancer Lynda Meyer Vane Vest *Role debut †U.S. opera debut PLACE AND TIME: The early 1900s, Paris Saturday, October 3 1981, at 8:00 PM Act I -- The Embassy of Pontevedro in Paris Tuesday, October 6 1981, at 8:00 PM Act II -- The garden of Anna Glawari's mansion Friday, October 9 1981, at 8:00 PM Act III -- Maxim's Tuesday, October 13 1981, at 7:30 PM Friday, October 16 1981, at 8:00 PM Wednesday, October 21 1981, at 8:00 PM Sunday, October 25 1981, at 1:00 PM Wednesday, October 28 1981, at 7:30 PM Saturday, October 31 1981, at 8:00 PM San Francisco War Memorial 1981 Die Lustige Witwe The Merry Widow Page 2 of 3 Opera Assn. -

Programme.Pdf

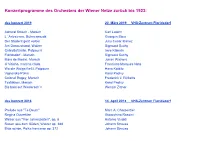

Konzertprogramme des Orchesters der Wiener Netze zurück bis 1923: das konzert 2019 20. März 2019 VHS-Zentrum Floridsdorf Admiral Stosch - Marsch Carl Latann L´ Arlesienne, Bühnenmusik Georges Bizet Der Student geht vorbei Juliu Cesar Ibanez Am Donaustrand, Walzer Sigmund Suchy Csárdásfürstin, Potpourri Imre Kálmán Floridsdorf - Marsch Sigmund Suchy Mars de Medici, Marsch Johan Wichers O Vitinho, marcha chula Francisco Marques Neto Wo die Wolga fließt, Potpourri Hans Kolditz Vajnorska Polka Karol Padivy Colonel Bogey, Marsch Frederick J. Ricketts Textilakov, Marsch Karol Padivy Bis bald auf Wiederseh´n Wenzel Zittner das konzert 2018 14. April 2018 VHS-Zentrum Floridsdorf Prelude aus "Te Deum" Marc A. Charpentier Regina Ouvertüre Gioacchino Rossini Winter aus "Vier Jahreszeiten", op. 8 Antonio Vivaldi Rosen aus dem Süden, Walzer op. 388 Johann Strauss Bitte schön, Polka francaise op. 372 Johann Strauss Der Vogelhändler, Potpourri Carl Zeller Triglav Marsch op. 72 Julius Fucik Harry Potter, Filmmusik John Williams Westside Story, Potpourri Leonard Bernstein Mixed Pickles Max Leemann Maxglaner Zigeunermarsch Tobias Reiser Für Österreichs Ehr´ Marsch Josef Lassletzberger Böhmische Musikanten, Polka Rudolf Lamp Dort tanzt Lulu, Walzer Will Meisel Faszination Blasmusik 22. Oktober 2017 Konzerthaus Triglav, Marsch op. 72 Julius Fucik Verträumte Melodien, Potpourri Hans Kolditz Tanzen möcht´ ich, Walzer Imre Kálmán das konzert 2017 22. April 2017 VHS-Zentrum Floridsdorf Abendgebet aus "Nachtlager in Granada" Conradin Kreutzer Eine Nacht in Venedig, Ouvertüre Johann Strauss Stephanie Gavotte, op. 312 Alphons Czibulka Erinnerung an Franz Schubert, Potpourri Johann Kliment Das liegt bei uns im Blut, Polka mazur op. 374 Carl M. Ziehrer Loreley-Rhein - Klänge, Walzer op. 154 Johann Strauss, Vater Per aspera ad astra, Marsch Ernst Urbach Khevenhüller Marsch Anton Fridrich The lion sleeps tonight Weiss / Creatore / Kampstra Fernando / Thank you for the music Benny Anderson / Björn Ulvaeus Persischer Marsch, op. -

DIE LUSTIGE WITWE Franz Lehár

DIE LUSTIGE WITWE Franz Lehár Logos to add to marketing materials Please make sure you incorporate the necessary partner logos on any printed or digital communications from your venue. This includes: website listings, flyers, posters, printed schedules, email blasts, banners, brochures and any other materials that you distribute. Logos for this production: Rising Alternative + Semperoper Dresden + Euroarts Libretto by Victor Léon and Leo Stein after the comedy L’attaché d’ambassade by Henri Meilhac. Opera in three acts Sung in German Recorded 2007 From Semperoper Dresden, Germany Approximately running time 2h23 CREATIVE TEAM Conductor Manfred Honeck Production Jérôme Savary Set design Ezio Toffolutti Choreography Nadège Maruta Produced by EuroArts, ZDF/ARTE in co-operation with the Compagnie Jérôme Savary. ARTISTIC TEAM Baron Mirko Zeta Gunther Emmerlich Valencienne Lydia Teuscher Graf Danilo Danilowitsch Bo Skovhus Hanna Glawari Petra-Maria Schnitzer Symphony Orchestra and Chorus of Staatsoper Dresden. PRESENTATION The Merry Widow (Die Lustige Witwe) had its premiere at Vienna's Theater an der Wien in 1905. Franz Lehár’s impressive entry into the world of operettas unexpectedly with The Merry Widow gave rise to a second resurgence of the genre. Often called “The Queen of Operettas”, this is certainly the most celebrated and successful show of its kind ever written. Frequently staged in an abridged version, this production from the Staatsoper Dresden features many musical numbers that are usually omitted. This staging by the famous opera director Jérôme Savary makes The Merry Widow a very colourful and a subtle tribute to the golden age of Hollywood. SYNOPSIS PROLOGUE ACT I The Paris embassy of the Balkan kingdom of Pontevedro. -

Kurmusik2019 Come As You Are

KURMUSIK2019 COME AS YOU ARE WUNSCHKONZERTE REPERTOIRELISTE „Eine ganz wunderbare Tradition der Kurmusik sind die Wunschkonzerte. Es ist immer wieder faszinierend mit welcher Sorgfalt und Leiden- schaft sich unsere Gäste Musikstücke wünschen, ihr eigenes Programm zusammenstellen. Während der Konzerte ist die Vorfreude auf den ganz persönlichen Musikwunsch zu spüren. Der Moment in dem der erste Ton des Stückes erklingt und die Gesichter zu strahlen beginnen - span- nend und berührend zugleich! Mit der Repertoire-Liste laden wir Sie ein Ihr ganz persönliches Lieblingsstück zu wählen.“ Gabriella Squarra Geschäftsführerin Bayerisches Staatsbad Bad Reichenhall Kur GmbH Bad Reichenhall / Bayerisch Gamin 2 KURMUSIK REPERTOIRE-LISTE 2019 WILLKOMMEN 2019 AUS DEM STAMMREPERTOIRE DER BAD REICHENHALLER PHILHARMONIKER FÜR DIE PHILHARMONISCHEN WUNSCHKONZERTE Für die über 150 Kurkonzerte welche die Bad Konzert-Ouvertüren, Konzert-Suiten, Reichenhaller Philharmoniker im Laufe einer Ballett-Suiten und Konzertstücke finden Saison musizieren, steht ihnen ein Repertoi- Sie summiert unter dem Überbegriff re von 455 Werken aus den verschiedensten „Konzertstücke“. Werkgattungen zur Verfügung. Darin nicht enthalten sind jene Werke die in einem Jahr Bitte werfen Sie Ihre Musikwünsche bis im Rahmen der Themen-Kurkonzerte auf Donnerstag Vormittag in den Briefkasten dem Programm stehen. an der Konzertrotunde, Eingang Salzburger Straße, ein. Oder senden Sie uns eine Email Damit Sie, sehr geehrte Musikfreunde, aus mit Ihren Wünschen an wunschkonzert@ diesem reichhaltigen und vielfältigen An- philharmonie-reichenhall.de.W ir gebot an Werken, Ihr besonderes Lieblings- bitten um Verständnis, dass wir nicht stück für das Wunschkonzert auswählen alle Musikwünsche erfüllen können! Die können, haben wir folgende Repertoireliste Stammrepertoireliste der Bad Reichenhaller auf zwei Arten erstellt. Philharmoniker finden Sie auch im Internet unter www.bad-reichenhall.de und Manche von Ihnen werden das gewünschte www.bad-reichenhaller-philharmoniker.de. -

ABSTRACT Developments in Viennese Operetta in Johann

ABSTRACT Developments in Viennese Operetta in Johann Strauss, Franz Lehár, and Robert Stolz Joanie Brittingham. M.M. Thesis Chairperson: Laurel E. Zeiss, Ph.D. The first immensely popular composer of Viennese operetta was Johann Strauss. Later composers, including Franz Lehár and Robert Stolz, became famous and wealthy for continuing the traditions of the genre as codified by Strauss. The most notable works of these composers either became part of the standard repertory or are considered historically important for the development of light opera and musical theatre in some way. Therefore, I studied the most important elements of the genre, namely the waltz, exoticism, and local color, and compared how each composer used these common building blocks in their most successful operettas. Developments in Viennese Operetta in Johann Strauss, Franz Lehár, and Robert Stolz by Joanie Brittingham, B.M. A Thesis Approved by the Department of Music ___________________________________ William V. May, Jr., Ph.D, Dean ___________________________________ David W. Music, D.M.A., Graduate Program Director Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ Laurel E. Zeiss, Ph.D., Chairperson ___________________________________ Jean Ann Boyd, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Deborah K. Williamson, D.M.A ___________________________________ Daniel E. Scott, D.M.A. ___________________________________ Wallace -

The Merry Widow (Die Lustige Witwe)

VANCOUVER OPERA PRESENTS Franz Lehár THE MERRY WIDOW (DIE LUSTIGE WITWE) STUDY GUIDE OPERETTA IN THREE ACTS Libretto by Viktor Léon and Leo Stein, In German with English SurTitles™ English Dialogue by Sheldon Harnick CONDUCTOR Ward Stare DIRECTOR Kelly Robinson CHOREOGRAPHER Joshua Beamish QUEEN ELIZABETH THEATRE October 20, 25, & 27 at 7:30pm | October 28 at 2pm DRESS REHEARSAL Thursday, October 18 at 7pm OPERA EXPERIENCE Thursday, October 25 at 7:30pm EDUCATION THE MERRY WIDOW VANCOUVER OPERA | STUDY GUIDE Franz Lehár THE MERRY WIDOW (DIE LUSTIGE WITWE) CAST IN ORDER OF VOCAL APPEARANCE VICOMTE CASCADA Michael Nyby BARON MIRKO ZETA Richard Suart VALENCIENNE Sasha Djihanian SYLVAINE Nicole Joanne* OLGA Dionne Sellinger PRASKOWIA Gena van Oosten* CAMILLE DE ROSILLON John Tessier RAOUL DE ST. BRIOCHE Scott Rumble* KROMOW Peter Monaghan# PRITCHITCH Daniel Thielmann* BOGDANOVITCH Jason Klippenstien NJEGUS Sarah Afful HANNA GLAWARI Lucia Cesaroni COUNT DANILO DANILOVITCH John Cudia With the Vancouver Opera Chorus and the Vancouver Opera Orchestra CHORUS DIRECTOR /ASSISTANT CONDUCTOR Kinza Tyrrell SCENIC DESIGNER Michael Yeargan COSTUME DESIGNER Susan Memmott-Allred LIGHTING DESIGNER Gerald King WIG DESIGNER Susan Manning MUSICAL PREPARATION Kinza Tyrrell, Angus Kellet, Perri Lo* STAGE MANAGER Jessica Severin ASSISTANT DIRECTOR Sarah Jane Pelzer* ENGLISH SURTITLE™ TRANSLATIONS Sarah Jane Pelzer* Member of the Yulanda M. Faris Young Artist Program* Alumni of the Yulanda M. Faris Young Artist Program# The performance will last approximately 3 hours. There will be 2 intermissions. First produced at the Theatre an der Wien, Vienna, December 30th 1905. First produced by Vancouver Opera, March 11, 1976. Sets courtesy of Utah Opera. Costumes courtesy of Utah Opera 1 vancouveropera.ca THE MERRY WIDOW VANCOUVER OPERA | STUDY GUIDE STUDY GUIDE OBJECTIVES This study guide has been designed to be accessible to all teachers regardless of previous experience in music or opera. -

The Merry Widow

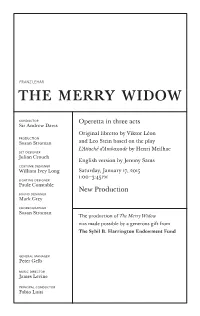

FRANZ LEHÁR the merry widow conductor Operetta in three acts Sir Andrew Davis Original libretto by Viktor Léon production Susan Stroman and Leo Stein based on the play L’Attaché d’Ambassade by Henri Meilhac set designer Julian Crouch English version by Jeremy Sams costume designer William Ivey Long Saturday, January 17, 2015 1:00–3:45 PM lighting designer Paule Constable New Production sound designer Mark Grey choreographer Susan Stroman The production of The Merry Widow was made possible by a generous gift from The Sybil B. Harrington Endowment Fund general manager Peter Gelb music director James Levine principal conductor Fabio Luisi The 32nd Metropolitan Opera performance of FRANZ LEHÁR’S the merry widow This performance is being broadcast live over The conductor Sir Andrew Davis Toll Brothers– Metropolitan Opera in order of vocal appearance International Radio vicomte cascada bogdanovitch Network, sponsored by Toll Brothers, Jeff Mattsey Mark Schowalter America’s luxury njegus ® baron mirko zeta homebuilder , with Sir Thomas Allen Carson Elrod generous long-term support from valencienne hanna gl awari The Annenberg Kelli O’Hara Renée Fleming Foundation, The Neubauer Family sylviane count danilo danilovitch Foundation, the Emalie Savoy* Nathan Gunn* Vincent A. Stabile olga woman Endowment for Wallis Giunta* Andrea Coleman Broadcast Media, and contributions pr askowia maître d’ from listeners Margaret Lattimore* Jason Simon worldwide. camille de rosillon griset tes There is no Alek Shrader LOLO Synthia Link Toll Brothers– DODO Alison Mixon r aoul de st. brioche Metropolitan Opera JOUJOU Emily Pynenburg Alexander Lewis* Quiz in List Hall today. FROUFROU Leah Hofmann CLOCLO kromow Jenny Laroche This performance is Daniel Mobbs MARGOT Catherine Hamilton also being broadcast live on Metropolitan pritschitsch Opera Radio on Gary Simpson SiriusXM channel 74. -

Strauß Sofiensaal

Kompositionen der Familie STRAUSS zusammengestellt von (uraufgeführt in den Sofiensälen) Dr. Harald SCHLOSSER Johann Strauß Vater Titel Kategorie op. Datum Widmung Souvenir de Carneval 1847 Quadrille 200 18.1.1847 "Ball der Nordbahnbeamten" Najaden-Quadrille Quadrille 206 2.2.1847 Frau Caroline Morawetz Schwedische Lieder Walzer 207 9.2.1847 Zur Erinnerung an die gefeyerte Sängerin Jenny Lind Fortuna-Polka Polka 219 29.2.1848 Amphion-Klänge. Techniker-Ball-Tänze Walzer 224 31.11848 Den Herren Technikern Aether-Träume. Mediciner-Ball-Tänze Walzer 225 8.2.1848 Der Hörern der Medizin an der Hochschule zu Wien ("Medizinerball") Die Sorgenbrecher Walzer 230 22.2.1848 Damen-Souvenir-Polka Polka 236 13.2.1849 Des Wanderers Lebewohl Walzer 237 13.2.1849 Die Friedens-Boten Walzer 241 24.1.1849 Johann Strauß Sohn Titel Kategorie op. Datum Widmung Frohsinns Spenden Walzer 73 16.1.1850 Lava-Ströme Walzer 74 29.1.1850 "Ball im Vesuv" Sophien-Quadrille Quadrille 75 13.1.1850 Attaque-Quadrille Quadrille 76 13.1.1850 (ev. 16.3.1850 - Sperl) Slaven-Ball-Quadrille Quadrille 88 17.2.1851 "Slavenball" Orakel-Sprüche Walzer 90 10.2.1851 Ball "Das delphische Orakel" Rhadamantus-Klänge Walzer 94 26.2.1851 Juristenball Windsor-Klänge Walzer 104 10.2.1852 Königin Victoria von Großbritannien und Irland (10.1.1852 Palais Coburg) Fünf Paragraphen aus dem Walzer-Codex Walzer 105 3.2.1852 Juristenball Harmonie-Polka ("Concordia-Polka") Polka 106 4.2.1852 Der protestantischen Gemeinde in Wien Electro-magnetische-Polka Polka 110 11.2.1852 Technikerball Satanella-Quadrille