Shuri Castle's Other History: Architecture and Empire in Okinawa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes Toward a Study of Neighborhood Festivals in Modern Tokyo

The Shrine : Notes toward a Study of Neighborhood Festivals in Modern Tokyo By A.W. S a d l e r Sarah Lawrence College When I arrived in Japan in the autumn of 1965, I settled my family into our home-away-from-home in a remote comer of Bunkyo-ku3 in Tokyo, and went to call upon an old timer,a man who had spent most of his adult life in Tokyo. I told him of my intention to carry out an exhaustive study of the annual festivals (taisai) of a typical neighbor hood shrine (jinja) in my area of residence,and I told him I had a full year at my disposal for the task. “Start on the grounds of the shrine/,was his solid advice; “go over every tsubo '(every square foot3 we might say),take note of every stone, investigate every marker.” And that is how I began. I worked with the shrines closest to home so that shrine and people would be part of my everyday life. When my wife and I went for an evening stroll, we invariably happened upon the grounds of one of our shrines; when we went to the market for fish or pencils or raaisnes we found ourselves visiting with the ujiko (parishioners; literally,children of the god of the shrine, who is guardian spirit of the neighborhood) of the shrine. I started with five shrines. I had great difficulty arranging for interviews with the priests of two of the five (the reasons for their reluc tance to visit with me will be discussed below) ; one was a little too large and famous for my purposes,and another was a little too far from home for really careful scrutiny. -

The Reliquaries of Hyrule: a Semiotic and Iconographic Analysis of Sacred Architecture Within Ocarina of Time

Press Start The Reliquaries of Hyrule The Reliquaries of Hyrule: A Semiotic and Iconographic Analysis of Sacred Architecture Within Ocarina of Time Jared Hansen University of Oregon Abstract This study is a semiotic and iconographic analysis of the sacred architecture in The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (Nintendo, 1998). Through an analysis of the visual elements of the game, the researcher found evidence of visual metaphors that coded three temples as sacred spaces. This coding of the temples is accomplished through the symbolism of progression that matches the design of shrines and cathedrals, drawing on iconography and other symbolism associated with Shinto, Buddhist, and Christian sacred architecture. Such indications of sacred spaces highlight the ways in which these virtual environments are designed to symbolize the progression of the player from secular to sacred, much like the player’s progression from zero to hero. By using the architecture and symbolism of the three aforementioned belief systems, Ocarina of Time signifies these temples as reliquaries—that is, sacred places that house reverential items as part of the apotheosis of the player. Keywords Art history; The Legend of Zelda; sacred space; symbolism; temple. Press Start 2021 | Volume 7 | Issue 1 ISSN: 2055-8198 URL: http://press-start.gla.ac.uk Press Start is an open access student journal that publishes the best undergraduate and postgraduate research, essays and dissertations from across the multidisciplinary subject of game studies. Press Start is published by HATII at the University of Glasgow. Hansen The Reliquaries of Hyrule Introduction The video game experiences that I remember and treasure most are the feelings I have within the virtual environments. -

2019 Annual Report

2019 Annual Report Te Hiranga Rū QuakeCoRE Aotearoa New Zealand Centre for Earthquake Resilience Contents ___ Directors’ Report 3 Chair’s Report 4 About Us 5 Our Outcomes 6 Research Research overview 7 Technology platforms 8 Flagship programmes 9 Other projects 10 Scrap tyres find new lives as earthquake protection 11 How effective is insurance for earthquake risk mitigation? 13 Toward functional buildings following major earthquakes 15 Collaboration to Impact Preparing for quakes: Seismic sensors and early warning systems 17 What makes a resilient community? 19 Collaboration a key tool in natural hazard public education 21 Human Capability Development Connections through quakes: International researchers tour New Zealand 23 Research in Te Ao Māori 25 The QuakeCoRE postgraduate experience 27 Recognition highlights 29 Financials, Community and Outputs Financials 33 At a glance 34 Community 35 Publications 41 Directors’ Report 2019 ___ Te Hiranga Rū QuakeCoRE formed in 2016 with a vision of transforming the QuakeCoRE continues to exhibit collaborative leadership domestically and earthquake resilience of communities throughout Aotearoa New Zealand, and in internationally. We highlight the strong alignment achieved with the ‘Resilience to four years, we are already seeing important progress toward this vision through our Nature’s Challenges’ National Science Challenge, progress associated with our on- focus on research excellence, deep national and international collaborations, and going commitment to Mātauranga Māori, partnership research between the public human capability development. and private sectors through community participation in seismic sensor deployment, and also the ‘Learning from Earthquakes’ programme as an example of international In our fourth Annual Report we highlight several world-class research stories, opportunities to study New Zealand as a natural earthquake laboratory. -

Pictures of an Island Kingdom Depictions of Ryūkyū in Early Modern Japan

PICTURES OF AN ISLAND KINGDOM DEPICTIONS OF RYŪKYŪ IN EARLY MODERN JAPAN A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ART HISTORY MAY 2012 By Travis Seifman Thesis Committee: John Szostak, Chairperson Kate Lingley Paul Lavy Gregory Smits Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Chapter I: Handscroll Paintings as Visual Record………………………………. 18 Chapter II: Illustrated Books and Popular Discourse…………………………. 33 Chapter III: Hokusai Ryūkyū Hakkei: A Case Study……………………………. 55 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………. 78 Appendix: Figures …………………………………………………………………………… 81 Works Cited ……………………………………………………………………………………. 106 ii Abstract This paper seeks to uncover early modern Japanese understandings of the Ryūkyū Kingdom through examination of popular publications, including illustrated books and woodblock prints, as well as handscroll paintings depicting Ryukyuan embassy processions within Japan. The objects examined include one such handscroll painting, several illustrated books from the Sakamaki-Hawley Collection, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library, and Hokusai Ryūkyū Hakkei, an 1832 series of eight landscape prints depicting sites in Okinawa. Drawing upon previous scholarship on the role of popular publishing in forming conceptions of “Japan” or of “national identity” at this time, a media discourse approach is employed to argue that such publications can serve as reliable indicators of understandings -

Through the Case of Izumo Taishakyo Mission of Hawaii

The Japanese and Okinawan American Communities and Shintoism in Hawaii: Through the Case of Izumo Taishakyo Mission of Hawaii A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʽI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN AMERICAN STUDIES MAY 2012 By Sawako Kinjo Thesis Committee: Dennis M. Ogawa, Chairperson Katsunori Yamazato Akemi Kikumura Yano Keywords: Japanese American Community, Shintoism in Hawaii, Izumo Taishayo Mission of Hawaii To My Parents, Sonoe and Yoshihiro Kinjo, and My Family in Okinawa and in Hawaii Acknowledgement First and foremost, I would like to express my deep and sincere gratitude to my committee chair, Professor Dennis M. Ogawa, whose guidance, patience, motivation, enthusiasm, and immense knowledge have provided a good basis for the present thesis. I also attribute the completion of my master’s thesis to his encouragement and understanding and without his thoughtful support, this thesis would not have been accomplished or written. I also wish to express my warm and cordial thanks to my committee members, Professor Katsunori Yamazato, an affiliate faculty from the University of the Ryukyus, and Dr. Akemi Kikumura Yano, an affiliate faculty and President and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the Japanese American National Museum, for their encouragement, helpful reference, and insightful comments and questions. My sincere thanks also goes to the interviewees, Richard T. Miyao, Robert Nakasone, Vince A. Morikawa, Daniel Chinen, Joseph Peters, and Jikai Yamazato, for kindly offering me opportunities to interview with them. It is a pleasure to thank those who made this thesis possible. -

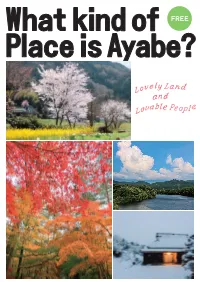

What-Kind-Place-Is-Ayabe.Pdf

What kind of Place is Ayabe? Lovely Land and Lovable People Table of Contents 1.Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City 2 2) The Land of Ayabe 6 3) The People of Ayabe 9 2. Four Seasons in Ayabe (Events and Flowers) 1)Spring ( from March to May ) 12 2)Summer ( from June to August ) 27 3)Autumn ( from September to November ) 38 4)Winter ( from December to February ) 51 3.Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations in Ayabe 1) Shinto and Shinto Shrines 57 2) Buddhism and Buddhist Temples 63 3) Other Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations 69 4) Shops, Cafés, Restaurants etc. 84 Ayabe City Sightseeing Map 88 C260A4AM21 この地図の作成に当っては、国土地理院長の承認を得て、同院発行の数値地図25000(地図画像)を使用した。(承認番号 平22業使、第632号)」 1. Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City Location The middle part of Kyoto Prefecture. It takes about one hour by train from Kyoto. Total Area 347.1 square kilometers Climate It belongs to the temperate zone. The average yearly temperature is 14.8 degrees Celsius. Population 33,821 people in 2015 Working The working population of commerce Population 2,002 people (in 2014) The working population of industry 4,786 people (in 2014) The working population of agriculture 2,914 people (in 2015) Established August 1, 1950 Mayor Zenya Yamazaki (as of 2017) Friendship Cities Jerusalem (Israel), Changshu (China) City Tree Pine City Flower Japanese plum blossoms City Bird Grosbeak (Ikaru) Schools Kyoto Prefectural Agricultural College Ayabe Senior High School Junior high schools 6 schools Elementary schools 10 schools Local Specialties Green tea Matsutake mushroom Chestnut Sweet fish (Ayu) Traditional Japanese hand-made paper (Kurotani Washi) Main Rivers Yura River, Kambayashi River, Sai River, Isazu River, Yata River High mountains M.Tokin (871meters), Mt. -

Description of Fences

Equestrian Park Equestrian 馬事公苑 馬術 / Sports équestres Parc Equestre Jumping Team 障害馬術団体 / Saut d'obstacles par équipes SAT 7 AUG 2021 Jump-Off) ジャンプオフ / Barrage Description of Fences フェンスの説明 / Description des obstacles Fence 1 – The Great Wave off Kanagawa. Hokusai. Author: (Katsushika Hokusai) Original Title: (Kanagawa-oki nami ura) Year: 1829 – 1832 Base/stand: Colour-engraved upon a wooden block. Japanese ukiyo-e master. The Great Wave is the most recognized piece by Japanese painter Katsushika Hokusai, who specializes in ukiyo-e. Published between 1830 and 1833 during the Edo period, it forms part of the collection “Thirty-six views of Mount Fuji”, even though Mount Fuji is the smallest element. The wave references the relentless force of nature, the sea, and the importance this event has in Japan’s economy and its cultural development, given the country is formed by 4 islands. EQUO JUMPTEAM----------FNL-0002RR--_03B 1 Report Created SAT 7 AUG 2021 16 :45 Page 1/7 Equestrian Park Equestrian 馬事公苑 馬術 / Sports équestres Parc Equestre Jumping Team 障害馬術団体 / Saut d'obstacles par équipes SAT 7 AUG 2021 Jump-Off) ジャンプオフ / Barrage Fence 4 – Mascot of the Tokyo 2020 Olympics Japanese illustrator Ryo Taniguchi. Manga and gamer references are seen, in representation of the Japanese contemporary visual culture and with a character design inspired by the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games’ Logo. The pair of futuristic characters combine tradition and innovation. The name of the Olympics mascot, Miraitowa, fuses the Japanese words for future and eternity. Someity, the Paralympics mascot, is derived from Somei-yoshino, a type of cherry blossom, cherry blossom variety "Someiyoshino" and is a play on words with the English phrase “So mighty”. -

Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J

Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei mandara Talia J. Andrei Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2016 © 2016 Talia J.Andrei All rights reserved Abstract Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J. Andrei This dissertation examines the historical and artistic circumstances behind the emergence in late medieval Japan of a short-lived genre of painting referred to as sankei mandara (pilgrimage mandalas). The paintings are large-scale topographical depictions of sacred sites and served as promotional material for temples and shrines in need of financial support to encourage pilgrimage, offering travelers worldly and spiritual benefits while inspiring them to donate liberally. Itinerant monks and nuns used the mandara in recitation performances (etoki) to lead audiences on virtual pilgrimages, decoding the pictorial clues and touting the benefits of the site shown. Addressing themselves to the newly risen commoner class following the collapse of the aristocratic order, sankei mandara depict commoners in the role of patron and pilgrim, the first instance of them being portrayed this way, alongside warriors and aristocrats as they make their way to the sites, enjoying the local delights, and worship on the sacred grounds. Together with the novel subject material, a new artistic language was created— schematic, colorful and bold. We begin by locating sankei mandara’s artistic roots and influences and then proceed to investigate the individual mandara devoted to three sacred sites: Mt. Fuji, Kiyomizudera and Ise Shrine (a sacred mountain, temple and shrine, respectively). -

The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance

•••••••• ••• •• • .. • ••••---• • • - • • ••••••• •• ••••••••• • •• ••• ••• •• • •••• .... ••• .. .. • .. •• • • .. ••••••••••••••• .. eo__,_.. _ ••,., .... • • •••••• ..... •••••• .. ••••• •-.• . PETER MlJRRAY . 0 • •-•• • • • •• • • • • • •• 0 ., • • • ...... ... • • , .,.._, • • , - _,._•- •• • •OH • • • u • o H ·o ,o ,.,,,. • . , ........,__ I- .,- --, - Bo&ton Public ~ BoeMft; MA 02111 The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance ... ... .. \ .- "' ~ - .· .., , #!ft . l . ,."- , .• ~ I' .; ... ..__ \ ... : ,. , ' l '~,, , . \ f I • ' L , , I ,, ~ ', • • L • '. • , I - I 11 •. -... \' I • ' j I • , • t l ' ·n I ' ' . • • \• \\i• _I >-. ' • - - . -, - •• ·- .J .. '- - ... ¥4 "- '"' I Pcrc1·'· , . The co11I 1~, bv, Glacou10 t l t.:• lla l'on.1 ,111d 1 ll01nc\ S t 1, XX \)O l)on1c111c. o Ponrnna. • The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance New Revised Edition Peter Murray 202 illustrations Schocken Books · New York • For M.D. H~ Teacher and Prie11d For the seamd edillo11 .I ltrwe f(!U,riucu cerurir, passtJgts-,wwbly thOS<' on St Ptter's awl 011 Pnlladfo~ clmrdses---mul I lr,rvl' takeu rhe t>pportrmil)' to itJcorporate m'1U)1 corrt·ctfons suggeSLed to nu.• byfriet1ds mu! re11iewers. T'he publishers lwvc allowed mr to ddd several nt•w illusrra,fons, and I slumld like 10 rltank .1\ Ir A,firlwd I Vlu,.e/trJOr h,'s /Jelp wft/J rhe~e. 711f 1,pporrrm,ty /t,,s 11/so bee,r ft1ke,; Jo rrv,se rhe Biblfogmpl,y. Fc>r t/Jis third edUfor, many r,l(lre s1m1II cluu~J!eS lwvi: been m"de a,,_d the Biblio,~raphy has (IJICt more hN!tl extet1si11ely revised dtul brought up to date berause there has l,een mt e,wrmc>uJ incretlJl' ;,, i111eres1 in lt.1lim, ,1rrhi1ea1JrP sittr<• 1963,. wlte-,r 11,is book was firs, publi$hed. It sh<>uld be 110/NI that I haw consistc11tl)' used t/1cj<>rm, 1./251JO and 1./25-30 to 111e,w,.firs1, 'at some poiHI betwt.·en 1-125 nnd 1430', .md, .stamd, 'begi,miug ilJ 1425 and rnding in 14.10'. -

Japanese Gardens at American World’S Fairs, 1876–1940 Anthony Alofsin: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Aesthetics of Japan

A Publication of the Foundation for Landscape Studies A Journal of Place Volume ıv | Number ı | Fall 2008 Essays: The Long Life of the Japanese Garden 2 Paula Deitz: Plum Blossoms: The Third Friend of Winter Natsumi Nonaka: The Japanese Garden: The Art of Setting Stones Marc Peter Keane: Listening to Stones Elizabeth Barlow Rogers: Tea and Sympathy: A Zen Approach to Landscape Gardening Kendall H. Brown: Fair Japan: Japanese Gardens at American World’s Fairs, 1876–1940 Anthony Alofsin: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Aesthetics of Japan Book Reviews 18 Joseph Disponzio: The Sun King’s Garden: Louis XIV, André Le Nôtre and the Creation of the Garden of Versailles By Ian Thompson Elizabeth Barlow Rogers: Gardens: An Essay on the Human Condition By Robert Pogue Harrison Calendar 22 Tour 23 Contributors 23 Letter from the Editor times. Still observed is a Marc Peter Keane explains Japanese garden also became of interior and exterior. The deep-seated cultural tradi- how the Sakuteiki’s prescrip- an instrument of propagan- preeminent Wright scholar tion of plum-blossom view- tions regarding the setting of da in the hands of the coun- Anthony Alofsin maintains ing, which takes place at stones, together with the try’s imperial rulers at a in his essay that Wright was his issue of During the Heian period winter’s end. Paula Deitz Zen approach to garden succession of nineteenth- inspired as much by gardens Site/Lines focuses (794–1185), still inspired by writes about this third friend design absorbed during his and twentieth-century as by architecture during his on the aesthetics Chinese models, gardens of winter in her narrative of long residency in Japan, world’s fairs. -

Watanabe, Tokyo, E

Edition Axel Menges GmbH Esslinger Straße 24 D-70736 Stuttgart-Fellbach tel. +49-711-574759 fax +49-711-574784 Hiroshi Watanabe The Architecture of Tokyo 348 pp. with 330 ill., 161,5 x 222 mm, soft-cover, English ISBN 3-930698-93-5 Euro 36.00, sfr 62.00, £ 24.00, US $ 42.00, $A 68.00 The Tokyo region is the most populous metropolitan area in the world and a place of extraordinary vitality. The political, economic and cultural centre of Japan, Tokyo also exerts an enormous inter- national influence. In fact the region has been pivotal to the nation’s affairs for centuries. Its sheer size, its concentration of resources and institutions and its long history have produced buildings of many different types from many different eras. Distributors This is the first guide to introduce in one volume the architec- ture of the Tokyo region, encompassing Tokyo proper and adja- Brockhaus Commission cent prefectures, in all its remarkable variety. The buildings are pre- Kreidlerstraße 9 sented chronologically and grouped into six periods: the medieval D-70806 Kornwestheim period (1185–1600), the Edo period (1600–1868), the Meiji period Germany (1868–1912), the Taisho and early Showa period (1912–1945), the tel. +49-7154-1327-33 postwar reconstruction period (1945–1970) and the contemporary fax +49-7154-1327-13 period (1970 until today). This comprehensive coverage permits [email protected] those interested in Japanese architecture or culture to focus on a particular era or to examine buildings within a larger temporal Buchzentrum AG framework. A concise discussion of the history of the region and Industriestraße Ost 10 the architecture of Japan develops a context within which the indi- CH-4614 Hägendorf vidual works may be viewed. -

Tokyo Great Garden Spring Campaign

Enlightenment with Asakura style philosophy 7RN\R Former AsakuraAsakura Fumio Garden (Asakura Museum of Sculpture, Taito) 7-18-10 Yanaka, Taito-ku 103-3821-4549 *UHDW National - designated Place of Scenic Beauty "Former Asakura Fumio Garden" Asakura Sculpture Museum is the building that was a studio and residence of Fumio Asakura (1883 ~1964) a leading sculptor of modern Japan. Asakura designed and supervised the building which was completed in 1935. Asakura died in 1964, but the building was opened to the public as a Asakura Sculpture Museum since 1967 by the family of the deceased (transferred to Taito-ku in 1986), in 2001 the building is registered in the tangible cultural heritage of the country. In 2008 the integration of architecture and gardens were admitted for their value and artistic appreciation and *DUGHQ the entire site has been designated as a national scenic spot as "The former gardens of Fumio Asakura". Since 2009 to 2013 was carried out conservation and restoration works on a large scale and appearance could be restored even when Asakura was alive. Admission General 500 yen (300 yen). Elementary, middle and high school students 250 yen (150 yen) *( ) inside is a group rate of more than 20 people *Persons holding the Handicapped person's passbook or a Certificate Issued for Specific Disease Treatment and their caregivers is free Yearly Passport: 1,000 yen (same price for all visitors) 6SULQJ Open 9:30 - 16:30 (Admission until 16:00) Closed Mondays and Thursdays Open on holidays and Closed on the day following a holidays Year-end and New Year holidays *During changing exhibitions, etc.