Sector-Level Impacts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birma Na Zakręcie. Zmiany W Kraju Tysiąca Pagód 2007–2014

BIRMA NA ZAKRĘCIE MIĘDZY DYKTATURĄ A DEMOKRACJĄ BIRMA NA ZAKRĘCIE. ZMIANY W KRAJU TYSIĄCA PAGÓD 2007–2014 „Złoty Budda Mahamuni siedzi w głębi głównej nawy. Na wysokości jego pępka widać rusztowanie, a na nim trzech uwijających się mężczyzn, którzy nieustannymi ruchami PRZEMYSŁAW GASZTOLD-SEŃ rąk jak gdyby poprawiają coś w posągu. [...] Zachęceni przez przewodnika, wdrapujemy pracownik Biura Edukacji Publicznej IPN, się na rusztowanie, ale jedna z belek przywiera tak ściśle do posągu, że aby przejść do doktorant na Wydziale Dziennikarstwa i Nauk Politycznych Uniwersytetu przodu i stanąć oko w oko z Buddą, trzeba na zakręcie oprzeć się rękami o jego ramię. Warszawskiego. Autor książki Konces- Czuję obiema dłońmi gorącą lepkość jakiejś mazi i prześlizgnąwszy się szybko na przedni jonowany nacjonalizm. Zjednoczenie pomost rusztowania, odrywam z instynktownym uczuciem wstrętu ręce od posągu: są Patriotyczne „Grunwald” 1980–1990 ubabrane złotem” – zanotował w maju 1952 r. Gustaw Herling-Grudziński w dzienniku (2012, Nagroda Historyczna „Polityki” z podróży do Birmy1. Od czasu jego wizyty w Mandalaj minęło ponad sześćdziesiąt lat2. za debiut, nominacja do Nagrody Przez ten długi czas posąg Buddy znacznie się rozrósł dzięki płatkom złota przylepianym im. Kazimierza Moczarskiego), współautor tomu Syria During the Cold War. The East codziennie przez setki pielgrzymów. Przywiązania do religii nie podminowały ani rządy European Connection (razem z Janem parlamentarne, ani pół wieku krwawej wojskowej dyktatury. Buddyzm wciąż stanowi Adamcem i Massimilianem Trentinem, najważniejszą wartość i punkt odniesienia dla większości Birmańczyków. 2014). We wrześniu 2007 r. i w listopadzie Jaka jest Birma dzisiaj? Czy po wielu latach autorytarnych rządów generałów wejdzie 2013 r. podróżował po Birmie. na drogę ku demokracji? Czy wydarzenia z ostatnich lat są autentycznym krokiem w stronę reformy systemu? Nie na wszystkie pytania znajdzie się jednoznaczną odpowiedź, ale warto pochylić się nad tym najmniej znanym krajem Azji Południowo-Wschodniej. -

Tourism Development in Thandaung Gyi a Grounded Theory Study On

Tourism Development in Thandaung Gyi A Grounded Theory Study on Tourism Development Thomas L. Maatjens Department of Geography, Planning and Environment, Radboud University Master Thesis Prof. Dr. Huib Ernste Feb. 28, 2020 i Preface The writing process of this thesis has been long and at times very hard for me. However, I am incredibly proud of the result, with which I am about to complete my Cultural Geography and Tourism master’s degree and thus conclude my studies at Radboud University Nijmegen. My time at Radboud University has been incredibly rewarding and I am looking forward to what the future might hold. The research and writing process of this thesis would not have been possible without the help of several people. First, I would like to thank my thesis supervisor Prof. Dr. Huib Ernste for his time and support. My time in the Republic of Myanmar would not have been as fulfilling as it was without the help of my internship supervisor Marlo Perry and the team of the Myanmar Responsible Tourism Institute in Yangon. I would like to thank them and the people of Thandaung Gyi for their hospitality and support. I would also like to thank Jan and Marlon for their support and last, but not least, I would like to thank my girlfriend Hannah for her love and dedication to me. Thomas L. Maatjens Nijmegen, February 28, 2020 ii Executive Summary This thesis seeks to understand the process of tourism development in Thandaung Gyi, within the context of the region’s economic development and ongoing peace process. -

Bilin, Thaton, Kyaikto and Hpa- an Townships, September to November 2014

Situation Update February 10, 2015 / KHRG #14-101-S1 Thaton Situation Update: Bilin, Thaton, Kyaikto and Hpa- an townships, September to November 2014 This Situation Update describes events occurring in Bilin, Thaton, Kyaikto and Hpa-an townships, Thaton District during the period between September to November 2014, including armed groups’ activities, forced labour, restrictions on the freedom of movement, development activities and access to education. th • On October 7 2014, Border Guard Force (BGF) Battalion #1014 Company Commander Tin Win from Htee Soo Kaw Village ordered A---, B---, C--- and D--- villagers to work for one day. Ten villagers had to cut wood, bamboo and weave baskets to repair the BGF army camp in C--- village, Hpa-an Township. • In Hpa-an Township, two highways were constructed at the beginning of 2013 and one highway was constructed in 2014. Due to the construction of the road, villagers who lived nearby had their land confiscated and their plants and crops were destroyed. They received no compensation, despite reporting the problem to Hpa-an Township authorities. • In the academic year of 2013-2014 more Burmese government teachers were sent to teach in Karen villages. Villagers are concerned as they are not allowed to teach the Karen language in the schools. Situation Update | Bilin, Thaton, Kyaikto and Hpa-an townships, Thaton District (September to November 2014) The following Situation Update was received by KHRG in December 2014. It was written by a community member in Thaton District who has been trained by KHRG to monitor local human rights conditions. It is presented below translated exactly as originally written, save for minor edits for clarity and security.1 This report was received along with other information from Thaton District, including one incident report.2 This report concerns the situation in the region, the villagers’ feelings, armed groups’ activities, forced labour, development activities, support to villagers and education problems occurring between the beginning of September and November 2014. -

The Myanmar-Thailand Corridor 6 the Myanmar-Malaysia Corridor 16 the Myanmar-Korea Corridor 22 Migration Corridors Without Labor Attachés 25

Online Appendixes Public Disclosure Authorized Labor Mobility As a Jobs Strategy for Myanmar STRENGTHENING ACTIVE LABOR MARKET POLICIES TO ENHANCE THE BENEFITS OF MOBILITY Public Disclosure Authorized Mauro Testaverde Harry Moroz Public Disclosure Authorized Puja Dutta Public Disclosure Authorized Contents Appendix 1 Labor Exchange Offices in Myanmar 1 Appendix 2 Forms used to collect information at Labor Exchange Offices 3 Appendix 3 Registering jobseekers and vacancies at Labor Exchange Offices 5 Appendix 4 The migration process in Myanmar 6 The Myanmar-Thailand corridor 6 The Myanmar-Malaysia corridor 16 The Myanmar-Korea corridor 22 Migration corridors without labor attachés 25 Appendix 5 Obtaining an Overseas Worker Identification Card (OWIC) 29 Appendix 6 Obtaining a passport 30 Cover Photo: Somrerk Witthayanant/ Shutterstock Appendix 1 Labor Exchange Offices in Myanmar State/Region Name State/Region Name Yangon No (1) LEO Tanintharyi Dawei Township Office Yangon No (2/3) LEO Tanintharyi Myeik Township Office Yangon No (3) LEO Tanintharyi Kawthoung Township Office Yangon No (4) LEO Magway Magwe Township Office Yangon No (5) LEO Magway Minbu District Office Yangon No (6/11/12) LEO Magway Pakokku District Office Yangon No (7) LEO Magway Chauk Township Office Yangon No (8/9) LEO Magway Yenangyaung Township Office Yangon No (10) LEO Magway Aunglan Township Office Yangon Mingalardon Township Office Sagaing Sagaing District Office Yangon Shwe Pyi Thar Township Sagaing Monywa District Office Yangon Hlaing Thar Yar Township Sagaing Shwe -

CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1 Country Profile

CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1 Country Profile Region: East Asia & Pacific (Known as Southeast Asia) Country: The Republic of Union of Myanmar Capital: Naypyidaw Largest City: Yangon (7,355,075 in 2014) Currency: Myanmar Kyat Population: 7 million (2017) GNI Per Capital: (U$$) 1,293 (2017) GDP: $94.87 billion (2017) GDP Growth: 9.0% (2017) Inflation: 10.8% 2017 (The World Bank, 2016) Language: Myanmar, several dialects and English Religion: Over 80 percent of Myanmar Theravada Buddhism. There are Christians, Muslims, Hindus, and some animists. Business Hours: Banks: 09:30 – 15:00 Mon –Fri Office: 09:30-16:00 Mon-Fri Airport Tax: 10 US Dollars for departure at international gates Customs: Foreign currencies (above USD 10000), jewelry, cameras And electronic goods must be declared to the customs at The airport. Exports of antiques and archaeologically Valuable items are prohibited. 2.2 Myanmar Tourism Overview Myanmar has been recorded as one of Asia’s most prosperous economies in the region before World War II and expected to gain rapid industrialization. The country belongs rich natural resources and one of most educated nations in Southeast Asia. However, Myanmar economic was getting worst after military coup in 1962, which transform to be one of the poorest nations in the region. “Then military government centrally planned and inward looking strategies such as nationalization of all major industries and import-substitution polices had long been pursued (Ni Lar, 2012)”. These strategies were laydown under General Nay Win leadership theory so called “Burmese Way to Socialism”. Since then, the country economic getting into problems such as ‘inactive in industrial production, high inflection, resign living cost, and macroeconomic mismanagement’. -

Mandalay, Pathein and Mawlamyine - Mandalay, Pathein and Mawlamyine

Urban Development Plan Development Urban The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Ministry of Construction for Regional Cities The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Urban Development Plan for Regional Cities - Mawlamyine and Pathein Mandalay, - Mandalay, Pathein and Mawlamyine - - - REPORT FINAL Data Collection Survey on Urban Development Planning for Regional Cities FINAL REPORT <SUMMARY> August 2016 SUMMARY JICA Study Team: Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. Nine Steps Corporation International Development Center of Japan Inc. 2016 August JICA 1R JR 16-048 Location業務対象地域 Map Pannandin 凡例Legend / Legend � Nawngmun 州都The Capital / Regional City Capitalof Region/State Puta-O Pansaung Machanbaw � その他都市Other City and / O therTown Town Khaunglanhpu Nanyun Don Hee 道路Road / Road � Shin Bway Yang � 海岸線Coast Line / Coast Line Sumprabum Tanai Lahe タウンシップ境Township Bou nd/ Townshipary Boundary Tsawlaw Hkamti ディストリクト境District Boundary / District Boundary INDIA Htan Par Kway � Kachinhin Chipwi Injangyang 管区境Region/S / Statetate/Regi Boundaryon Boundary Hpakan Pang War Kamaing � 国境International / International Boundary Boundary Lay Shi � Myitkyina Sadung Kan Paik Ti � � Mogaung WaingmawミッチMyitkyina� ーナ Mo Paing Lut � Hopin � Homalin Mohnyin Sinbo � Shwe Pyi Aye � Dawthponeyan � CHINA Myothit � Myo Hla Banmauk � BANGLADESH Paungbyin Bhamo Tamu Indaw Shwegu Katha Momauk Lwegel � Pinlebu Monekoe Maw Hteik Mansi � � Muse�Pang Hseng (Kyu Koke) Cikha Wuntho �Manhlyoe (Manhero) � Namhkan Konkyan Kawlin Khampat Tigyaing � Laukkaing Mawlaik Tonzang Tarmoenye Takaung � Mabein -

SIRP Fourpager

Midwife Aye Aye Nwe greets one of her young patients at the newly constructed Rural Health Centre in Kyay Thar Inn village (Tanintharyi Region). PHOTO: S. MARR, BANYANEER More engaged, better connected In brief: results of the Southeast Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project (SIRP), Myanmar I first came to this village”, says Aye Aye Nwe, Following Myanmar’s reform process and ceasefires with local “When “things were so different.” Then 34 years old, the armed groups, the opportunity arose to finally improve conditions midwife first came to Kyay Thar Inn village in 2014. - advancing health, education, infrastructure, basic services. “It was my first post. When I arrived, there was no clinic. The The task was huge, and remains considerable today despite village administrators had built a house for me - but it was not a the progress that has been achieved over recent years. clinic! Back then, villagers had no full coverage of vaccinations and healthcare - neither for prevention nor treatment.” The project The Southeast Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project (SIRP) was The nearest rural health centre was eleven kilometres away - a designed to support this process. Starting in late 2012, a long walk over roads that are muddy in the wet season and dusty consortium of Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), the Swiss in the dry. Unsurprisingly, says Nwe, “the health knowledge of Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), the Karen villagers was quite poor. They did not know that immunisations Development Network (KDN)* and Action Aid Myanmar (AAM) are a must. Women did not get antenatal care or assistance of sought to enhance lives and living conditions in 89 remote midwives during delivery.” villages across Myanmar’s southeast. -

Report Administration of Burma

REPORT ON THE ADMINISTRATION OF BURMA FOR THE YEAR 1933=34 RANGOON SUPDT., GOVT. PRINTING AND STATIONERY, BURMA 1935 LIST OF AGENTS FOR THE SALE~OF GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN BURMA. AllERICAN BAPTIST llIISSION PRESS, Rangoon. BISWAS & Co., 226 Lewis Street, Rangoon. BRITISH BURMA PRESS BRANCH, Rangoon .. ·BURMA BOO!, CLUB, LTD., Poat Box No. 1068, Rangoon. - NEW LIGHT 01' BURlL\ Pl?ESS, 61 Sule Pagoda Road, Rangoon. PROPRIETOR, THU DHA!IIA \VADI PRE,S, 16-80 lliaun!l :m,ine Street. Rangoon. RANGOOX TIMES PRESS, Rangoon. THE CITY BOOK CLUB, 98 Phayre Street, Rangoon . l\IESSRS, K. BIN HOON & Soi.:s, Nyaunglebin. MAUNG Lu GALE, Law Book Depot, 42 Ayo-o-gale. Manrlalay. ·CONTINENTAL TR.-\DDiG co.. No. 353 Lower Main Road. ~Ioulmein. lN INDIA. BOOK Co., Ltd., 4/4A College Sq<1are, Calcutta. BUTTERWORTH & Co. Undlal, "Ltd., Calcutta . .s. K. LAHIRI & Co., 56 College Street, Calcutta. ,v. NEWMAN & Co., Calcutta. THACKER, SPI:-K & Co., Calcutta, and Simla. D. B. TARAPOREVALA, Soxs & Co., Bombay. THACKER & Co., LTD., Bombay. CITY BOO!! Co., Post Box No. 283, l\Iadras. H!GGINBOTH.UI:& Co., Madras. ·111R. RA~I NARAIN LAL, Proprietor, National1Press, Katra.:Allahabad. "MESSRS. SAllPSON WILL!A!II & Co., Cawnpore, United Provinces, IN }j:URUPE .-I.ND AMERICA, -·xhc publications are obtainable either ~direct from THE HIGH COMMISS!Oli:ER FOR INDIA, Public Department, India House Aldwych, London, \V.C. 2, or through any bookseller. TABLE OF CONTENTS. :REPORT ON THE ADMINISTRATION OF BURMA FOR THE YEAR 1933-34. Part 1.-General Summary. Part 11.-Departmental Chapters. CHAPTER !.-PHYSICAL AND POLITICAT. GEOGRAPHY. "PHYSICAL-- POLITICAL-co11clcl. -

Myanmar Hotel & Tourism Review 2012

MMRD BUSINESS INSIGHT MYANMAR HOTEL & TOURISM REVIEW 2012 ● ● ● T J Tan [Pick the date] Page | 2 Contents Country Facts ● ● ● .......................................................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary ● ● ● ................................................................................................................ 6 Overview ● ● ● ................................................................................................................................ 7 Infrastructure ............................................................................................................................... 7 There has been much progress in infrastructure development particularly in the past 2 years. This would include: ....................................................................................................................... 7 Banking, Payment & Foreign Exchange ........................................................................................ 8 Investments .................................................................................................................................. 8 Tax .............................................................................................................................................. 11 Communications ......................................................................................................................... 11 Tourism Sector ● ● ● .................................................................................................................... -

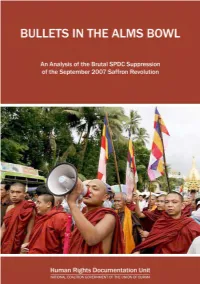

Bullets in the Alms Bowl

BULLETS IN THE ALMS BOWL An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution March 2008 This report is dedicated to the memory of all those who lost their lives for their part in the September 2007 pro-democracy protests in the struggle for justice and democracy in Burma. May that memory not fade May your death not be in vain May our voices never be silenced Bullets in the Alms Bowl An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution Written, edited and published by the Human Rights Documentation Unit March 2008 © Copyright March 2008 by the Human Rights Documentation Unit The Human Rights Documentation Unit (HRDU) is indebted to all those who had the courage to not only participate in the September protests, but also to share their stories with us and in doing so made this report possible. The HRDU would like to thank those individuals and organizations who provided us with information and helped to confirm many of the reports that we received. Though we cannot mention many of you by name, we are grateful for your support. The HRDU would also like to thank the Irish Government who funded the publication of this report through its Department of Foreign Affairs. Front Cover: A procession of Buddhist monks marching through downtown Rangoon on 27 September 2007. Despite the peaceful nature of the demonstrations, the SPDC cracked down on protestors with disproportionate lethal force [© EPA]. Rear Cover (clockwise from top): An assembly of Buddhist monks stage a peaceful protest before a police barricade near Shwedagon Pagoda in Rangoon on 26 September 2007 [© Reuters]; Security personnel stepped up security at key locations around Rangoon on 28 September 2007 in preparation for further protests [© Reuters]; A Buddhist monk holding a placard which carried the message on the minds of all protestors, Sangha and civilian alike. -

UNIVERSITY of GOTHENBURG School of Global Studies

UNIVERSITY OF GOTHENBURG School of Global Studies A host society’s perception of changes in its young peoples’ cultural identity due to tourism: A case study in Bagan, Myanmar Master thesis in Global Studies Spring Semester 2014 Higher Education Credits: 30 HEC Author: Anna-Katharina Rich Supervisor: Anja Karlsson Franck Word Count: 19 528 Acknowledgements............................................................................................................ 4 Abstract ............................................................................................................................. 5 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 6 2. Aim and research questions............................................................................................ 7 3. Relevance to global studies ............................................................................................ 8 4. Delimitation ................................................................................................................... 9 5. Theoretical approach.................................................................................................... 10 5.1. Cultural identity ....................................................................................................................................................... 10 5.1.1. (Cultural) identity in post-conflict societies............................................................................................. -

Tourism and Regional Integration in Southeast Asia’ from July 2012 to January 2013

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I owe a deep debt of gratitude to the Institute of Developing Economies (IDE- JETRO) for the opportunity to conduct a research project on the ‘tourism and regional integration in Southeast Asia’ from July 2012 to January 2013. I would like to express my sincere appreciation to the staff and researchers of the institute for their warm hospitality. My knowledge and research experience have been enriched thanks to the large pool of diverse experts working on various issues in different regions and countries. I am especially indebted to my research counterpart, Ms. Maki Aoki, and research advisor, Ms. Etsuyo Arai, for their constructive comments and encouragement throughout the research writing process. I would like to thank Ms. Naomi Hatsukano and Mr. Makishima Minoru for introducing me to this program and their continued support during my stay at IDE. In addition, I am grateful to IDE research fellows, especially Mr. Nobuhiro Aizawa, Mr. Takahiro Fukunishi, Mr. Kenmei Tsubota, Mr. Kiyoyasu Tanaka, Mr. Yasushi Ueki and Mr. Kazu Hayakawa for their time and friendship. I would like to thank all the staff members working at the International Exchange Division, Research Coordination Office, and Library for always being approachable and responsive and for their excellent work in making the life of visiting fellows here comfortable and enjoyable. In particular, I am indebted to Mr. Takao Tsuneishi, Ms. Chisato Ishii, Mr. Tatsufumi Yamagata, Mr. Koshi Yamada and Mr. Taiki Koga for their support and friendship. Many thanks also go to all the visiting fellows (Ms. Gao, Prof. Scarlett, Prof. Somchai, Prof. Ramaswamy and Prof.