Late Jurassic Dinosaurs on the Move, Gastroliths and Long-Distance Migration" (2019)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mesozoic—Dinos!

MESOZOIC—DINOS! VOLUME 9, ISSUE 8, APRIL 2020 THIS MONTH DINOSAURS! • Dinosaurs ○ What is a Dinosaur? page 2 DINOSAURS! When people think paleontology, ○ Bird / Lizard Hip? page 5 they think of scientists ○ Size Activity 1 page 10 working in the hot sun of ○ Size Activity 2 page 13 Colorado National ○ Size Activity 3 page 43 Monument or the Badlands ○ Diet page 46 of South Dakota and ○ Trackways page 53 Wyoming finding enormous, ○ Colorado Fossils and fierce, and long-gone Dinosaurs page 66 dinosaurs. POWER WORDS Dinosaurs safely evoke • articulated: fossil terror. Better than any bones arranged in scary movie, these were Articulated skeleton of the Tyrannosaurus rex proper order actually living breathing • endothermic: an beasts! from the American Museum of Natural History organism produces body heat through What was the biggest dinosaur? be reviewing the information metabolism What was the smallest about dinosaurs, but there is an • metabolism: chemical dinosaur? What color were interview with him at the end of processes that occur they? Did they live in herds? this issue. Meeting him, you will within a living organism What can their skeletons tell us? know instantly that he loves his in order to maintain life What evidence is there so that job! It doesn’t matter if you we can understand more about become an electrician, auto CAREER CONNECTION how these animals lived. Are mechanic, dancer, computer • Meet Dr. Holtz, any still alive today? programmer, author, or Dinosaur paleontologist, I truly hope that Paleontologist! page 73 To help us really understand you have tremendous job more about dinosaurs, we have satisfaction, like Dr. -

Triassic- Jurassic Stratigraphy Of

Triassic- Jurassic Stratigraphy of the <JF C7 JL / Culpfeper and B arbour sville Basins, VirginiaC7 and Maryland/ ll.S. PAPER Triassic-Jurassic Stratigraphy of the Culpeper and Barboursville Basins, Virginia and Maryland By K.Y. LEE and AJ. FROELICH U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1472 A clarification of the Triassic--Jurassic stratigraphic sequences, sedimentation, and depositional environments UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON: 1989 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR MANUEL LUJAN, Jr., Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Lee, K.Y. Triassic-Jurassic stratigraphy of the Culpeper and Barboursville basins, Virginia and Maryland. (U.S. Geological Survey professional paper ; 1472) Bibliography: p. Supt. of Docs. no. : I 19.16:1472 1. Geology, Stratigraphic Triassic. 2. Geology, Stratigraphic Jurassic. 3. Geology Culpeper Basin (Va. and Md.) 4. Geology Virginia Barboursville Basin. I. Froelich, A.J. (Albert Joseph), 1929- II. Title. III. Series. QE676.L44 1989 551.7'62'09755 87-600318 For sale by the Books and Open-File Reports Section, U.S. Geological Survey, Federal Center, Box 25425, Denver, CO 80225 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract.......................................................................................................... 1 Stratigraphy Continued Introduction... .......................................................................................... -

Cambrian Ordovician

Open File Report LXXVI the shale is also variously colored. Glauconite is generally abundant in the formation. The Eau Claire A Summary of the Stratigraphy of the increases in thickness southward in the Southern Peninsula of Michigan where it becomes much more Southern Peninsula of Michigan * dolomitic. by: The Dresbach sandstone is a fine to medium grained E. J. Baltrusaites, C. K. Clark, G. V. Cohee, R. P. Grant sandstone with well rounded and angular quartz grains. W. A. Kelly, K. K. Landes, G. D. Lindberg and R. B. Thin beds of argillaceous dolomite may occur locally in Newcombe of the Michigan Geological Society * the sandstone. It is about 100 feet thick in the Southern Peninsula of Michigan but is absent in Northern Indiana. The Franconia sandstone is a fine to medium grained Cambrian glauconitic and dolomitic sandstone. It is from 10 to 20 Cambrian rocks in the Southern Peninsula of Michigan feet thick where present in the Southern Peninsula. consist of sandstone, dolomite, and some shale. These * See last page rocks, Lake Superior sandstone, which are of Upper Cambrian age overlie pre-Cambrian rocks and are The Trempealeau is predominantly a buff to light brown divided into the Jacobsville sandstone overlain by the dolomite with a minor amount of sandy, glauconitic Munising. The Munising sandstone at the north is dolomite and dolomitic shale in the basal part. Zones of divided southward into the following formations in sandy dolomite are in the Trempealeau in addition to the ascending order: Mount Simon, Eau Claire, Dresbach basal part. A small amount of chert may be found in and Franconia sandstones overlain by the Trampealeau various places in the formation. -

Asteroid Impact, Not Volcanism, Caused the End-Cretaceous Dinosaur Extinction

Asteroid impact, not volcanism, caused the end-Cretaceous dinosaur extinction Alfio Alessandro Chiarenzaa,b,1,2, Alexander Farnsworthc,1, Philip D. Mannionb, Daniel J. Luntc, Paul J. Valdesc, Joanna V. Morgana, and Peter A. Allisona aDepartment of Earth Science and Engineering, Imperial College London, South Kensington, SW7 2AZ London, United Kingdom; bDepartment of Earth Sciences, University College London, WC1E 6BT London, United Kingdom; and cSchool of Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol, BS8 1TH Bristol, United Kingdom Edited by Nils Chr. Stenseth, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, and approved May 21, 2020 (received for review April 1, 2020) The Cretaceous/Paleogene mass extinction, 66 Ma, included the (17). However, the timing and size of each eruptive event are demise of non-avian dinosaurs. Intense debate has focused on the highly contentious in relation to the mass extinction event (8–10). relative roles of Deccan volcanism and the Chicxulub asteroid im- An asteroid, ∼10 km in diameter, impacted at Chicxulub, in pact as kill mechanisms for this event. Here, we combine fossil- the present-day Gulf of Mexico, 66 Ma (4, 18, 19), leaving a crater occurrence data with paleoclimate and habitat suitability models ∼180 to 200 km in diameter (Fig. 1A). This impactor struck car- to evaluate dinosaur habitability in the wake of various asteroid bonate and sulfate-rich sediments, leading to the ejection and impact and Deccan volcanism scenarios. Asteroid impact models global dispersal of large quantities of dust, ash, sulfur, and other generate a prolonged cold winter that suppresses potential global aerosols into the atmosphere (4, 18–20). These atmospheric dinosaur habitats. -

Playing Robinson's Wall Game

Hands On Earth Science Activity No. 13 Playing Robinson’s Wall Game This activity can be used to help teach the following Topics and Content Statements for the Ohio Revised Science Standards (2018) and Model Curriculum (2019): Content Grade Topic Content Statement/Subtopic Standard Properties of Everyday K.PS.1: Objects and materials can be sorted and described Kindergarten Physical Science Objects and Materials by their properties. 3.ESS.1: Earth’s nonliving resources have specific Grade 3 Earth and Space Science Earth’s Resources properties. Grade 4 Earth and Space Science Earth’s Surface 4.ESS.2: The surface of Earth changes due to weathering. 6.ESS.2: Igneous, metamorphic and sedimentary rocks Grade 6 Earth and Space Science Rocks, Minerals and Soil have unique characteristics that can be used for identification and/or classification. Igneous, Metamorphic and Grades 9–12 Physical Geology Multiple connections Sedimentary Rocks No. 13 PLAYING ROBINSON’S WALL GAME by Joseph T. Hannibal, The Cleveland Museum of Natural History There is probably a stone wall somewhere near you. The wall may be a fence or a foundation or other part of a building. Such stone walls can be fascinating geologically, especially if they are constructed of more than one kind of stone. For students at any level, they make excellent places for hands-on dis- covery. Stone fences generally are made with local bedrock or, in glaciated areas, with local glacial erratics. In the case of buildings, many older structures are made of local stone; more recent buildings may be made of more exotic stones imported to the area for a particular project. -

The Geologic Time Scale Is the Eon

Exploring Geologic Time Poster Illustrated Teacher's Guide #35-1145 Paper #35-1146 Laminated Background Geologic Time Scale Basics The history of the Earth covers a vast expanse of time, so scientists divide it into smaller sections that are associ- ated with particular events that have occurred in the past.The approximate time range of each time span is shown on the poster.The largest time span of the geologic time scale is the eon. It is an indefinitely long period of time that contains at least two eras. Geologic time is divided into two eons.The more ancient eon is called the Precambrian, and the more recent is the Phanerozoic. Each eon is subdivided into smaller spans called eras.The Precambrian eon is divided from most ancient into the Hadean era, Archean era, and Proterozoic era. See Figure 1. Precambrian Eon Proterozoic Era 2500 - 550 million years ago Archaean Era 3800 - 2500 million years ago Hadean Era 4600 - 3800 million years ago Figure 1. Eras of the Precambrian Eon Single-celled and simple multicelled organisms first developed during the Precambrian eon. There are many fos- sils from this time because the sea-dwelling creatures were trapped in sediments and preserved. The Phanerozoic eon is subdivided into three eras – the Paleozoic era, Mesozoic era, and Cenozoic era. An era is often divided into several smaller time spans called periods. For example, the Paleozoic era is divided into the Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Carboniferous,and Permian periods. Paleozoic Era Permian Period 300 - 250 million years ago Carboniferous Period 350 - 300 million years ago Devonian Period 400 - 350 million years ago Silurian Period 450 - 400 million years ago Ordovician Period 500 - 450 million years ago Cambrian Period 550 - 500 million years ago Figure 2. -

A Mesoproterozoic Iron Formation PNAS PLUS

A Mesoproterozoic iron formation PNAS PLUS Donald E. Canfielda,b,1, Shuichang Zhanga, Huajian Wanga, Xiaomei Wanga, Wenzhi Zhaoa, Jin Sua, Christian J. Bjerrumc, Emma R. Haxenc, and Emma U. Hammarlundb,d aResearch Institute of Petroleum Exploration and Development, China National Petroleum Corporation, 100083 Beijing, China; bInstitute of Biology and Nordcee, University of Southern Denmark, 5230 Odense M, Denmark; cDepartment of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management, Section of Geology, University of Copenhagen, 1350 Copenhagen, Denmark; and dTranslational Cancer Research, Lund University, 223 63 Lund, Sweden Contributed by Donald E. Canfield, February 21, 2018 (sent for review November 27, 2017; reviewed by Andreas Kappler and Kurt O. Konhauser) We describe a 1,400 million-year old (Ma) iron formation (IF) from Understanding the genesis of the Fe minerals in IFs is one step the Xiamaling Formation of the North China Craton. We estimate toward understanding the relationship between IFs and the this IF to have contained at least 520 gigatons of authigenic Fe, chemical and biological environment in which they formed. For comparable in size to many IFs of the Paleoproterozoic Era (2,500– example, the high Fe oxide content of many IFs (e.g., refs. 32, 34, 1,600 Ma). Therefore, substantial IFs formed in the time window and 35) is commonly explained by a reaction between oxygen and between 1,800 and 800 Ma, where they are generally believed to Fe(II) in the upper marine water column, with Fe(II) sourced have been absent. The Xiamaling IF is of exceptionally low thermal from the ocean depths. The oxygen could have come from ex- maturity, allowing the preservation of organic biomarkers and an change equilibrium with oxygen in the atmosphere or from ele- unprecedented view of iron-cycle dynamics during IF emplace- vated oxygen concentrations from cyanobacteria at the water- ment. -

Redalyc.Lost Terranes of Zealandia: Possible Development of Late

Andean Geology ISSN: 0718-7092 [email protected] Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería Chile Adams, Christopher J Lost Terranes of Zealandia: possible development of late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic sedimentary basins at the southwest Pacific margin of Gondwanaland, and their destination as terranes in southern South America Andean Geology, vol. 37, núm. 2, julio, 2010, pp. 442-454 Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería Santiago, Chile Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=173916371010 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Andean Ge%gy 37 (2): 442-454. July. 2010 Andean Geology formerly Revista Geológica de Chile www.scielo.cl/andgeol.htm Lost Terranes of Zealandia: possible development of late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic sedimentary basins at the southwest Pacific margin of Gondwana land, and their destination as terranes in southern South America Christopher J. Adams GNS Science, Private Bag 1930, Dunedin, New Zealand. [email protected] ABSTRACT. Latesl Precambrian to Ordovician metasedimentary suecessions and Cambrian-Ordovician and Devonian Carboniferous granitoids form tbe major par! oftbe basemenl of soutbem Zealandia and adjacenl sectors ofAntarctica and southeastAustralia. Uplift/cooling ages ofthese rocks, and local Devonian shallow-water caver sequences suggest tbal final consolidation oftbe basemenl occurred tbrough Late Paleozoic time. A necessary consequence oftlris process would have been contemporaneous erosion and tbe substantial developmenl of marine sedimentary basins al tbe Pacific margin of Zealandia. -

The Late Jurassic Tithonian, a Greenhouse Phase in the Middle Jurassic–Early Cretaceous ‘Cool’ Mode: Evidence from the Cyclic Adriatic Platform, Croatia

Sedimentology (2007) 54, 317–337 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3091.2006.00837.x The Late Jurassic Tithonian, a greenhouse phase in the Middle Jurassic–Early Cretaceous ‘cool’ mode: evidence from the cyclic Adriatic Platform, Croatia ANTUN HUSINEC* and J. FRED READ *Croatian Geological Survey, Sachsova 2, HR-10000 Zagreb, Croatia Department of Geosciences, Virginia Tech, 4044 Derring Hall, Blacksburg, VA 24061, USA (E-mail: [email protected]) ABSTRACT Well-exposed Mesozoic sections of the Bahama-like Adriatic Platform along the Dalmatian coast (southern Croatia) reveal the detailed stacking patterns of cyclic facies within the rapidly subsiding Late Jurassic (Tithonian) shallow platform-interior (over 750 m thick, ca 5–6 Myr duration). Facies within parasequences include dasyclad-oncoid mudstone-wackestone-floatstone and skeletal-peloid wackestone-packstone (shallow lagoon), intraclast-peloid packstone and grainstone (shoal), radial-ooid grainstone (hypersaline shallow subtidal/intertidal shoals and ponds), lime mudstone (restricted lagoon), fenestral carbonates and microbial laminites (tidal flat). Parasequences in the overall transgressive Lower Tithonian sections are 1– 4Æ5 m thick, and dominated by subtidal facies, some of which are capped by very shallow-water grainstone-packstone or restricted lime mudstone; laminated tidal caps become common only towards the interior of the platform. Parasequences in the regressive Upper Tithonian are dominated by peritidal facies with distinctive basal oolite units and well-developed laminate caps. Maximum water depths of facies within parasequences (estimated from stratigraphic distance of the facies to the base of the tidal flat units capping parasequences) were generally <4 m, and facies show strongly overlapping depth ranges suggesting facies mosaics. Parasequences were formed by precessional (20 kyr) orbital forcing and form parasequence sets of 100 and 400 kyr eccentricity bundles. -

A Comparison of the Dinosaur Communities from the Middle

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 31 July 2018 doi:10.20944/preprints201807.0610.v1 Peer-reviewed version available at Geosciences 2018, 8, 327; doi:10.3390/geosciences8090327 1 Review 2 A comparison of the dinosaur communities from 3 the Middle Jurassic of the Cleveland (Yorkshire) 4 and Hebrides (Skye) basins, based on their ichnites 5 6 Mike Romano 1*, Neil D. L. Clark 2 and Stephen L. Brusatte 3 7 1 Independent Researcher, 14 Green Lane, Dronfield, Sheffield S18 2LZ, England, United Kingdom; 8 [email protected] 9 2 Curator of Palaeontology, The Hunterian, University of Glasgow, University Avenue, Glasgow 10 G12 8QQ, Scotland, United Kingdom; [email protected] 11 3 Chancellor's Fellow in Vertebrate Palaeontology, School of Geosciences, University of Edinburgh, 12 Grant Institute, The King's Buildings, James Hutton Road, Edinburgh EH9 3FE, Scotland, United Kingdom; 13 [email protected] 14 * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: 01246 417330 15 16 Abstract: 17 Despite the Hebrides and Cleveland basins being geographically close, research has not 18 previously been carried out to determine faunal similarities and assess the possibility of links 19 between the dinosaur populations. The palaeogeography of both areas during the Middle Jurassic 20 shows that there were no elevated landmasses being eroded to produce conglomeratic material in 21 the basins at that time. The low-lying landscape and connected shorelines may have provided 22 connectivity between the two dinosaur populations. 23 The dinosaur fauna of the Hebrides and Cleveland basins has been assessed based primarily 24 on the abundant ichnites found in both areas as well as their skeletal remains. -

MBMG 657 Maurice Mtn 24K.Ai

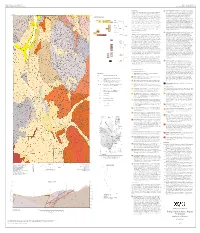

MONTANA BUREAU OF MINES AND GEOLOGY MBMG Open-File Report 657 ; Plate 1 of 1 A Department of Montana Tech of The University of Montana Geologic Map of the Maurice Mountain 7.5' Quadrangle, 2015 INTRODUCTION YlcYlc Lawson Creek Formation (Mesoproterozoic)—Characterized by couplets (cm-scale) and couples (dm-scale) of fine- to medium-grained white to pink quartzite and red, purple, black, A collaborative Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology–Idaho Geological Survey (MBMG–IGS) and green argillite. Lenticular and flaser bedding are common and characteristic. Mud rip-up mapping project began in 2007 to resolve some long-standing controversies concerning the clasts are locally common, and some are as much as 15 cm in diameter. Thick intervals of 113° 07' 30" 5' 2' 30" R 12 W 113° 00' relationships between two immensely thick, dissimilar, Mesoproterozoic sedimentary sequences: the 45° 37' 30" 45° 37' 30" medium-grained, thick-bedded (m-scale) quartzite are commonly interbedded with the TKg TKg Lemhi Group and the Belt Supergroup (Ruppel, 1975; Winston and others, 1999; Evans and Green, argillite-rich intervals. The quartzite intervals appear similar to the upper part of the CORRELATION DIAGRAM 32 2003; O’Neill and others, 2007; Burmester and others, 2013). The Maurice Mountain 7.5′ quadrangle underlying Swauger Formation (unit Ysw), but quartz typically comprises a large percentage 20 Ybl occupies a key location for study of these Mesoproterozoic strata, as well as for examination of of the grains (up to 93 percent) in contrast to the feldspathic Swauger Formation. Except in Qaf 45 Tcg Ybl 40 Ybl Holocene important Proterozoic through Tertiary tectonic features. -

And Early Jurassic Sediments, and Patterns of the Triassic-Jurassic

and Early Jurassic sediments, and patterns of the Triassic-Jurassic PAUL E. OLSEN AND tetrapod transition HANS-DIETER SUES Introduction parent answer was that the supposed mass extinc- The Late Triassic-Early Jurassic boundary is fre- tions in the tetrapod record were largely an artifact quently cited as one of the thirteen or so episodes of incorrect or questionable biostratigraphic corre- of major extinctions that punctuate Phanerozoic his- lations. On reexamining the problem, we have come tory (Colbert 1958; Newell 1967; Hallam 1981; Raup to realize that the kinds of patterns revealed by look- and Sepkoski 1982, 1984). These times of apparent ing at the change in taxonomic composition through decimation stand out as one class of the great events time also profoundly depend on the taxonomic levels in the history of life. and the sampling intervals examined. We address Renewed interest in the pattern of mass ex- those problems in this chapter. We have now found tinctions through time has stimulated novel and com- that there does indeed appear to be some sort of prehensive attempts to relate these patterns to other extinction event, but it cannot be examined at the terrestrial and extraterrestrial phenomena (see usual coarse levels of resolution. It requires new fine- Chapter 24). The Triassic-Jurassic boundary takes scaled documentation of specific faunal and floral on special significance in this light. First, the faunal transitions. transitions have been cited as even greater in mag- Stratigraphic correlation of geographically dis- nitude than those of the Cretaceous or the Permian junct rocks and assemblages predetermines our per- (Colbert 1958; Hallam 1981; see also Chapter 24).