Diseases of Echinoderms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Lophophorates" Brachiopoda Echinodermata Asterozoa

Deuterostomes Bryozoa Phoronida "lophophorates" Brachiopoda Echinodermata Asterozoa Stelleroidea Asteroidea Ophiuroidea Echinozoa Holothuroidea Echinoidea Crinozoa Crinoidea Chaetognatha (arrow worms) Hemichordata (acorn worms) Chordata Urochordata (sea squirt) Cephalochordata (amphioxoius) Vertebrata PHYLUM CHAETOGNATHA (70 spp) Arrow worms Fossils from the Cambrium Carnivorous - link between small phytoplankton and larger zooplankton (1-15 cm long) Pharyngeal gill pores No notochord Peculiar origin for mesoderm (not strictly enterocoelous) Uncertain relationship with echinoderms PHYLUM HEMICHORDATA (120 spp) Acorn worms Pharyngeal gill pores No notochord (Stomochord cartilaginous and once thought homologous w/notochord) Tornaria larvae very similar to asteroidea Bipinnaria larvae CLASS ENTEROPNEUSTA (acorn worms) Marine, bottom dwellers CLASS PTEROBRANCHIA Colonial, sessile, filter feeding, tube dwellers Small (1-2 mm), "U" shaped gut, no gill slits PHYLUM CHORDATA Body segmented Axial notochord Dorsal hollow nerve chord Paired gill slits Post anal tail SUBPHYLUM UROCHORDATA Marine, sessile Body covered in a cellulose tunic ("Tunicates") Filter feeder (» 200 L/day) - perforated pharnx adapted for filtering & repiration Pharyngeal basket contractable - squirts water when exposed at low tide Hermaphrodites Tadpole larvae w/chordate characteristics (neoteny) CLASS ASCIDIACEA (sea squirt/tunicate - sessile) No excretory system Open circulatory system (can reverse blood flow) Endostyle - (homologous to thyroid of vertebrates) ciliated groove -

Sediment Distribution, Hydrolytic Enzyme Profiles and Bacterial Activities in the Guts of Oneirophanta Mutabilis, Psychropotes L

Progress in Oceanography 50 (2001) 443–458 www.elsevier.com/locate/pocean Sediment distribution, hydrolytic enzyme profiles and bacterial activities in the guts of Oneirophanta mutabilis, Psychropotes longicauda and Pseudostichopus villosus: what do they tell us about digestive strategies of abyssal holothurians? D. Roberts a,*, H.M. Moore a, J. Berges a, J.W. Patching b, M.W. Carton b, D.F. Eardly b a School of Biology and Biochemistry, The Queen’s University, Belfast, Northern Ireland, UK b Marine Microbiology, Ryan Institute, University College, Galway, Ireland Abstract This paper describes inter-specific differences in the distribution of sediment in the gut compartments and in the enzyme and bacterial profiles along the gut of abyssal holothurian species — Oneirophanta mutabilis, Psychropotes longicauda and Pseudostichopus villosus sampled from a eutrophic site in the NE Atlantic at different times of the year. Proportions of sediments, relative to total gut contents, in the pharynx, oesophagus, anterior and posterior intestine differed significantly in all the inter-species comparisons, but not between inter-seasonal comparisons. Significant differ- ences were also found between the relative proportions of sediments in both the rectum and cloaca of Psychropotes longicauda and Oneirophanta mutabilis. Nineteen enzymes were identified in either gut-tissue or gut-content samples of the holothurians studied. Concentrations of the enzymes in gut tissues and their contents were highly correlated. Greater concentrations of the enzymes were found in the gut tissues suggesting that they are the main source of the enzymes. The suites of enzymes recorded were broadly similar in each of the species sampled collected regardless of the time of the year, and they were similar to those described previously for shallow-water holothurians. -

TEXT-BOOKS of ANIMAL BIOLOGY a General Zoology of The

TEXT-BOOKS OF ANIMAL BIOLOGY * Edited by JULIAN S. HUXLEY, F.R.S. A General Zoology of the Invertebrates by G. S. Carter Vertebrate Zoology by G. R. de Beer Comparative Physiology by L. T. Hogben Animal Ecology by Challes Elton Life in Inland Waters by Kathleen Carpenter The Development of Sex in Vertebrates by F. W. Rogers Brambell * Edited by H. MUNRO Fox, F.R.S. Animal Evolution / by G. S. Carter Zoogeography of the Land and Inland Waters by L. F. de Beaufort Parasitism and Symbiosis by M. Caullery PARASITISM AND ~SYMBIOSIS BY MAURICE CAULLERY Translated by Averil M. Lysaght, M.Sc., Ph.D. SIDGWICK AND JACKSON LIMITED LONDON First Published 1952 !.lADE AND PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LlMITED, LONDON AND BECCLES CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS vii PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH EDITION xi CHAPTER I Commensalism Introduction-commensalism in marine animals-fishes and sea anemones-associations on coral reefs-widespread nature of these relationships-hermit crabs and their associates CHAPTER II Commensalism in Terrestrial Animals Commensals of ants and termites-morphological modifications in symphiles-ants.and slavery-myrmecophilous plants . 16 CHAPTER III From Commensalism to Inquilinism and Parasitism Inquilinism-epizoites-intermittent parasites-general nature of modifications produced by parasitism 30 CHAPTER IV Adaptations to Parasitism in Annelids and Molluscs Polychates-molluscs; lamellibranchs; gastropods 40 CHAPTER V Adaptation to Parasitism in the Crustacea Isopoda-families of Epicarida-Rhizocephala-Ascothoracica -

Beach Treasures

BEACH TREASURES – HAVE YOU SEEN THEM? … Peter Crowcroft, Eco-Logic Education and Environment Services … Drawings by Kaye Traynor As the weather warms, and walking on the beach becomes much more appealing, keep a lookout along the high tide line for these two interesting, but rarely seen, beach treasures. Argonauta nodosa: Known as the Knobby Argonaut, or often, mistakenly, called the Paper Nautilus, this animal is actually a species of octopus that freely swims in the open ocean, in what is known as the pelagic zone – i.e. neither close to the bottom nor near the shore. It is in the family Argonautidae. Females of this species grow significantly larger than males, and secrete their paper-thin egg casing, that is such a rare and special find along our southern Australian beaches. To find a specimen in pristine condition, without any breakages, is considered by many as the pinnacle of beach combing fortune. Although this fragile structure acts as a shell, protecting and housing the female argonaut, it is unlike other cephalopod, true shells, and is regarded as an evolutionary novelty, unique to this family. The egg casing is typically around 150 mm in length, though some extraordinary Argonauta nodosa Knobby Argonaut specimens at 250 mm, or even larger, are known to grace some mantelpieces. Due to the radical dimorphism between male and females, not much was known about male Argonauts until relatively recently. Unlike the females, they do not secrete and live in an egg case, they reach only a fraction of the female size, and live a much shorter lifespans – only mating once, unlike the females that produce numerous broods of eggs throughout their lives. -

Thirteen New Records of Marine Invertebrates and Two of Fishes from Cape Verde Islands

Thirteen new records of marine invertebrates and two of fishes from Cape Verde Islands PETER WIRTZ Wirtz, P. 2009. Thirteen new records of marine invertebrates and two of fishes from Cape Verde Islands. Arquipélago. Life and Marine Sciences 26: 51-56. The sea anemones Actinoporus elegans Duchassaing, 1850 and Anthothoe affinis (Johnson, 1861) are new records from Cape Verde Islands. Also new to the marine fauna of Cape Verde are an undescribed mysid species of the genus Heteromysis that lives in association with the polychaete Branchiomma nigromaculata, the shrimp Tulearicoaris neglecta Chace, 1969 that lives in association with the sea urchin Diadema antillarum, an undescribed nudibranch of the genus Hypselodoris, and two undescribed species of the parasitic gastropod genus Melanella and Melanella cf. eburnea. An undescribed plathelmint of the genus Pseudobiceros, the nudibranch Phyllidia flava (Aradas, 1847) and the parasitic gastropod Echineulima leucophaes (Tomlin & Shackleford, 1913) are recorded, based on colour photos taken in the field. The crab Nepinnotheres viridis Manning, 1993 was encountered in the bivalve Pseudochama radians, which represents the first host record for this pinnotherid species. The nudibranch Tambja anayana, previously only known from a single animal, was reencountered and photographed alive. The sea anemone Actinoporus elegans, previously only known from the western Atlantic, is also reported here from São Tomé Island. In addition, the bythiid fish Grammonus longhursti and an undescribed species of the genus Apletodon are recorded from the Cape Verde Islands for the first time. Key words: Anthozoa, Gastropoda, marine biodiversity, Plathelmintes, São Tomé Peter Wirtz (e-mail: [email protected]), Centro de Ciências do Mar, Universidade do Algarve, Campus de Gambelas, PT-8005-139 Faro, Portugal. -

TREATISE TREATISE Paleo.Ku.Edu/Treatise

TREATISE TREATISE paleo.ku.edu/treatise For each fossil group, volumes describe and illustrate: morphological features; ontogeny; classification; geologic distribution; evolutionary trends and phylogeny; and All 53 volumes of the Treatise are now available as fully searchable pdf systematic descriptions. Each volume is fully indexed and files on CD, even out-of-print and superseded volumes! Also available contains a complete set of references, and there are many is the complete set of volumes, either on one DVD, or a set of 41 CDs, detailed illustrations and plates throughout the series. each decorated with a different fossil. See below for details. Complete set of 53 Treatise volumes Part B Single DVD or 41 CDs: $1850.00 Protoctista 1: Charophyta, vol. 1 Edited by Roger L. Kaesler, with coordinating author, Monique Feist, Porifera (Revised), vol. 2 Part F leading a team of international specialists, 2005 edited by Roger L. Kaesler; coordinating author, J. Keith Rigby, with First volume of Part B to be published, covering generally plantlike authors R. E. H. Reid, R.M. Finks, and J. Keith Rigby, 2003 Coelenterata, Supplement 1, Rugosa and Tabulata, vol. 1–2 autotrophic protoctists. Future volumes will cover the dinoflagellates, Second volume in the revision of Porifera. General features of the Porifera, edited by C. Teichert, coordinating author Dorothy Hill, 1981 silicoflagellates, ebredians, benthic calcareous algae, coccolithophorids, including glossary, references, and index. Introduction to Paleozoic corals and systematic descriptions for Rugosa; and diatoms. Included in the charophyte volume are introductory chapters 376 p., ISBN 0-8137-3130-5, $75.00, hard copy or CD introduction to and systematic descriptions for Tabulata. -

Proceedings of the United States National Museum

PROCEEDINGS OF THE UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM Issued SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION U. S. NATIONAL MUSEUM Vol. 102 Washington: 1952 No. 3302 ECHINODERMS FROM THE MARSHALL ISLANDS By Austin H. Clark The echinoderms from the Marshall Islands recorded in this re- port were collected during Operation Crossroads by the Oceano- graphic Section of Joint Task Force One under the direction of Commander Roger Revelle in 1946, and by the Bikini Scientific Re- survey under the direction of Capt. Christian L. Engleman in 1947. The number of species of echinoderms, exclusive of holothurians, in these two collections is 80, represented by 2,674 specimens. Although many of these have not previously been recorded from these islands, a number known from the group were not found, while others that certainly occur there still remain undiscovered. Of the 80 species collected, 22 were found only in 1946 and 24 only in 1947; only 34, about 40 percent, were found in both years. It is therefore impossible to appraise the effects, if any, of the explosion of the atomic bombs. But the specimens of the 54 species collected in 1947 are all quite normal. On the basis of the scanty and inadequate data available it would seem that the bombs had no appreciable effect on the echinoderms. Some of the species are represented by young individuals only. This is always the case in any survey of the echinoderm fauna of any tropical region. A few localities are found to yield nothing but young individuals of certain species at a given time, or possibly unless collections are made over a series of years. -

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS of the 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project March 2018 DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project Citation: Aguilar, R., García, S., Perry, A.L., Alvarez, H., Blanco, J., Bitar, G. 2018. 2016 Deep-sea Lebanon Expedition: Exploring Submarine Canyons. Oceana, Madrid. 94 p. DOI: 10.31230/osf.io/34cb9 Based on an official request from Lebanon’s Ministry of Environment back in 2013, Oceana has planned and carried out an expedition to survey Lebanese deep-sea canyons and escarpments. Cover: Cerianthus membranaceus © OCEANA All photos are © OCEANA Index 06 Introduction 11 Methods 16 Results 44 Areas 12 Rov surveys 16 Habitat types 44 Tarablus/Batroun 14 Infaunal surveys 16 Coralligenous habitat 44 Jounieh 14 Oceanographic and rhodolith/maërl 45 St. George beds measurements 46 Beirut 19 Sandy bottoms 15 Data analyses 46 Sayniq 15 Collaborations 20 Sandy-muddy bottoms 20 Rocky bottoms 22 Canyon heads 22 Bathyal muds 24 Species 27 Fishes 29 Crustaceans 30 Echinoderms 31 Cnidarians 36 Sponges 38 Molluscs 40 Bryozoans 40 Brachiopods 42 Tunicates 42 Annelids 42 Foraminifera 42 Algae | Deep sea Lebanon OCEANA 47 Human 50 Discussion and 68 Annex 1 85 Annex 2 impacts conclusions 68 Table A1. List of 85 Methodology for 47 Marine litter 51 Main expedition species identified assesing relative 49 Fisheries findings 84 Table A2. List conservation interest of 49 Other observations 52 Key community of threatened types and their species identified survey areas ecological importanc 84 Figure A1. -

Reinterpretation of the Enigmatic Ordovician Genus Bolboporites (Echinodermata)

Reinterpretation of the enigmatic Ordovician genus Bolboporites (Echinodermata). Emeric Gillet, Bertrand Lefebvre, Véronique Gardien, Emilie Steimetz, Christophe Durlet, Frédéric Marin To cite this version: Emeric Gillet, Bertrand Lefebvre, Véronique Gardien, Emilie Steimetz, Christophe Durlet, et al.. Reinterpretation of the enigmatic Ordovician genus Bolboporites (Echinodermata).. Zoosymposia, Magnolia Press, 2019, 15 (1), pp.44-70. 10.11646/zoosymposia.15.1.7. hal-02333918 HAL Id: hal-02333918 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02333918 Submitted on 13 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 Reinterpretation of the Enigmatic Ordovician Genus Bolboporites 2 (Echinodermata) 3 4 EMERIC GILLET1, BERTRAND LEFEBVRE1,3, VERONIQUE GARDIEN1, EMILIE 5 STEIMETZ2, CHRISTOPHE DURLET2 & FREDERIC MARIN2 6 7 1 Université de Lyon, UCBL, ENSL, CNRS, UMR 5276 LGL-TPE, 2 rue Raphaël Dubois, F- 8 69622 Villeurbanne, France 9 2 Université de Bourgogne - Franche Comté, CNRS, UMR 6282 Biogéosciences, 6 boulevard 10 Gabriel, F-2100 Dijon, France 11 3 Corresponding author, E-mail: [email protected] 12 13 Abstract 14 Bolboporites is an enigmatic Ordovician cone-shaped fossil, the precise nature and systematic affinities of 15 which have been controversial over almost two centuries. -

CONE SHELLS - CONIDAE MNHN Koumac 2018

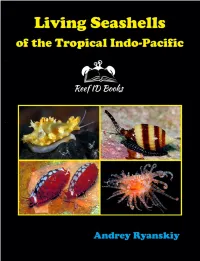

Living Seashells of the Tropical Indo-Pacific Photographic guide with 1500+ species covered Andrey Ryanskiy INTRODUCTION, COPYRIGHT, ACKNOWLEDGMENTS INTRODUCTION Seashell or sea shells are the hard exoskeleton of mollusks such as snails, clams, chitons. For most people, acquaintance with mollusks began with empty shells. These shells often delight the eye with a variety of shapes and colors. Conchology studies the mollusk shells and this science dates back to the 17th century. However, modern science - malacology is the study of mollusks as whole organisms. Today more and more people are interacting with ocean - divers, snorkelers, beach goers - all of them often find in the seas not empty shells, but live mollusks - living shells, whose appearance is significantly different from museum specimens. This book serves as a tool for identifying such animals. The book covers the region from the Red Sea to Hawaii, Marshall Islands and Guam. Inside the book: • Photographs of 1500+ species, including one hundred cowries (Cypraeidae) and more than one hundred twenty allied cowries (Ovulidae) of the region; • Live photo of hundreds of species have never before appeared in field guides or popular books; • Convenient pictorial guide at the beginning and index at the end of the book ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The significant part of photographs in this book were made by Jeanette Johnson and Scott Johnson during the decades of diving and exploring the beautiful reefs of Indo-Pacific from Indonesia and Philippines to Hawaii and Solomons. They provided to readers not only the great photos but also in-depth knowledge of the fascinating world of living seashells. Sincere thanks to Philippe Bouchet, National Museum of Natural History (Paris), for inviting the author to participate in the La Planete Revisitee expedition program and permission to use some of the NMNH photos. -

Hemichordate Phylogeny: a Molecular, and Genomic Approach By

Hemichordate Phylogeny: A molecular, and genomic approach by Johanna Taylor Cannon A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama May 4, 2014 Keywords: phylogeny, evolution, Hemichordata, bioinformatics, invertebrates Copyright 2014 by Johanna Taylor Cannon Approved by Kenneth M. Halanych, Chair, Professor of Biological Sciences Jason Bond, Associate Professor of Biological Sciences Leslie Goertzen, Associate Professor of Biological Sciences Scott Santos, Associate Professor of Biological Sciences Abstract The phylogenetic relationships within Hemichordata are significant for understanding the evolution of the deuterostomes. Hemichordates possess several important morphological structures in common with chordates, and they have been fixtures in hypotheses on chordate origins for over 100 years. However, current evidence points to a sister relationship between echinoderms and hemichordates, indicating that these chordate-like features were likely present in the last common ancestor of these groups. Therefore, Hemichordata should be highly informative for studying deuterostome character evolution. Despite their importance for understanding the evolution of chordate-like morphological and developmental features, relationships within hemichordates have been poorly studied. At present, Hemichordata is divided into two classes, the solitary, free-living enteropneust worms, and the colonial, tube- dwelling Pterobranchia. The objective of this dissertation is to elucidate the evolutionary relationships of Hemichordata using multiple datasets. Chapter 1 provides an introduction to Hemichordata and outlines the objectives for the dissertation research. Chapter 2 presents a molecular phylogeny of hemichordates based on nuclear ribosomal 18S rDNA and two mitochondrial genes. In this chapter, we suggest that deep-sea family Saxipendiidae is nested within Harrimaniidae, and Torquaratoridae is affiliated with Ptychoderidae. -

Biodiversidad De Los Equinodermos (Echinodermata) Del Mar Profundo Mexicano

Biodiversidad de los equinodermos (Echinodermata) del mar profundo mexicano Francisco A. Solís-Marín,1 A. Laguarda-Figueras,1 A. Durán González,1 A.R. Vázquez-Bader,2 Adolfo Gracia2 Resumen Nuestro conocimiento de la diversidad del mar profundo en aguas mexicanas se limita a los escasos estudios existentes. El número de especies descritas es incipiente y los registros taxonómicos que existen provienen sobre todo de estudios realizados por ex- tranjeros y muy pocos por investigadores mexicanos, con los cuales es posible conjuntar algunas listas faunísticas. Es importante dar a conocer lo que se sabe hasta el momen- to sobre los equinodermos de las zonas profundas de México, información básica para diversos sectores en nuestro país, tales como los tomadores de decisiones y científicos interesados en el tema. México posee hasta el momento 643 especies de equinoder- mos reportadas en sus aguas territoriales, aproximadamente el 10% del total de las especies reportadas en todo el planeta (~7,000). Según los registros de la Colección Nacional de Equinodermos (ICML, UNAM), la Colección de Equinodermos del “Natural History Museum, Smithsonian Institution”, Washington, DC., EUA y la bibliografía revisa- 1 Colección Nacional de Equinodermos “Ma. E. Caso Muñoz”, Laboratorio de Sistemá- tica y Ecología de Equinodermos, Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología (ICML), Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). Apdo. Post. 70-305, México, D. F. 04510, México. 2 Laboratorio de Ecología Pesquera de Crustáceos, Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Lim- nología (ICML), (UNAM), Apdo. Postal 70-305, México D. F., 04510, México. 215 da, existen 348 especies de equinodermos que habitan las aguas profundas mexicanas (≥ 200 m) lo que corresponde al 54.4% del total de las especies reportadas para el país.