'Danzanravjaa Is My Hero!': the Transformation of Tradition In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5033

Globalization ’s Impact on Mongolian Identity Issues and the Image of Chinggis Khan Alicia J. Campi PART I: The Mongols, this previously unheard-of nation that unexpectedly emerged to terrorize the whole world for two hundred years, disappeared again into obscurity with the advent of firearms. Even so, the name Mongol became one forever familiar to humankind, and the entire stretch of the thirteenth through the fifteenth centuries has come to be known as the Mongol era.' PART II; The historic science was the science, which has been badly affect ed, and the people of Mongolia bid farewell to their history and learned by heart the bistort' with distortion but fuU of ideolog}'. Because of this, the Mong olians started to forget their religious rituals, customs and traditions and the pa triotic feelings of Mongolians turned to the side of perishing as the internation alism was put above aU.^ PART III: For decades, Mongolia had subordinated national identity to So viet priorities __Now, they were set adrift in a sea of uncertainty, and Mongol ians were determined to define themselves as a nation and as a people. The new freedom was an opportunity as well as a crisis." As the three above quotations indicate, identity issues for the Mongolian peoples have always been complicated. In our increas ingly interconnected, media-driven world culture, nations with Baabar, Histoij of Mongolia (Ulaanbaatar: Monsudar Publishing, 1999), 4. 2 “The Political Report of the First Congress of the Mongolian Social-Demo cratic Party” (March 31, 1990), 14. " Tsedendamdyn Batbayar, Mongolia’s Foreign Folicy in the 1990s: New Identity and New Challenges (Ulaanbaatar: Institute for Strategic Studies, 2002), 8. -

P Mo 7 2 2001.Pdf

CONTENTS TEXTS AND MANUSCRIPTS: DESCRIPTION AND RESEARCH. 3 \'. Kushev. Thc Dawn of Pashtun Linguistics: Early Grammatical and Lexicographical Works and Their Manuscripts 3 M. \'orobyorn-Dcsyato\'skaya. A Sanskrit Manuscript on Birch-Bark from Bairam-Ali. 11. .frad£111a and ./iiruku (Part 3) 10 M. Rezrnn. Qu1"anic Fragments from the A. A. Polovtsov Collection at the St. Petersburg Branch of the Institute of Oriental Studies 20 PRESENTING THE COLLECTIONS. 36 E. Rczrnn. Oricntal Manuscripts of Karl Faberge. II: R<lgamii/c/ Miniatures of the Album (Muraqqa ') (Part One) 36 D. \'lorozo\'. Forgotten Oriental Documents 46 PRESENTING THE MANUSCRIPT. 50 I. Petrosyan. A Late Copy of the Glwrlh-mlma by · Ashiq-pasha 50 .\. KhaiidO\. A Manuscript of an Anthology by al-Abt. 60 ORIENTAL ICONOGRAPHY 64 0. Akimushkin. Arabic-Script Sources on Kamal al-Din Bchziid 64 BOOK REVIEWS. 69 F r o n t c o v e r: "Desvarati (Varari. Yaradi) Ragin!', watercolour. gouache and gold on p!per. Deccan. second half of the 18th century. Album (Muraqqa ') X 3 in the Karl Faberge collection at the St. Petersburg Branch of the Institute of Oriental Sti.rlics. fol. 25 a, 11.5 x 17 .0 cm. Back cover: "La Ii ta Raginf', watercolour. gouaehe and gold on paper. Dcrcan. second half of the 18th century. Same Album. fol. 34 b, 13.5 x 23.0 cm. THESA PUBLISHERS I\ CO-OPERA TIO\ WITH ST. PETERSBURG BRANCH OF THE INSTITUTE OF ORIENTAL STUDIES RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES £l!lnnuscriptn Orientnlin "'nternntionnl dournnl for OrientAI tl'!Jnnusrript .?esenrrh Vol. 7 No. -

Exploring the Persistence of Mongolian Women Leaders Holly D

Antioch University AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive Student & Alumni Scholarship, including Dissertations & Theses Dissertations & Theses 2019 Centuries of Navigating Resistance and Change: Exploring the Persistence of Mongolian Women Leaders Holly D. Diaz Antioch University - PhD Program in Leadership and Change Follow this and additional works at: https://aura.antioch.edu/etds Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, Leadership Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Diaz, Holly D., "Centuries of Navigating Resistance and Change: Exploring the Persistence of Mongolian Women Leaders" (2019). Dissertations & Theses. 485. https://aura.antioch.edu/etds/485 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student & Alumni Scholarship, including Dissertations & Theses at AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations & Theses by an authorized administrator of AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Centuries of Navigating Resistance and Change: Exploring the Persistence of Mongolian Women Leaders Holly Diaz ORCID Scholar ID# 0000-0001-9344-2729 A Dissertation Submitted to the PhD in Leadership and Change Program of Antioch University in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2019 This dissertation has been approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in Leadership and Change, Graduate School of Leadership and Change, Antioch University. Dissertation Committee • Elizabeth Holloway, Ph.D., Committee Chair • Tony Lingham, Ph.D., Committee Member • Karen Stout, Ph.D., Committee Member Copyright 2019 Holly Diaz All Rights Reserved Acknowledgements They say it takes a village, and this dissertation process was no exception. -

The Interplay Between Text and Image: the Molon Toyin's Tale

The Interplay between Text and Image: The Molon Toyin’s Tale Vesna A. Wallace, University of California, Santa Barbara Wallace, Vesna A. “The Interplay between Text and Image: The Molon Toyin’s Tale.” Cross- Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review 31: 58– 81. https://cross- currents.berkeley.edu/e-journal/issue-31/wallace. Abstract The anonymous illustrated manuscript of the Molon Toyin’s tale examined in this article is one of many narrative illustrations of popular Buddhist tales that circulated in Mongolia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and that have come to us in different lengths and forms. This article seeks to demonstrate that when a text and the accompanying narrative illustrations are brought together in a single manuscript, they enhance each other’s productive efficacy through their respective verbal and pictorial imagery. An illustrated text cross-references between the linguistic and visual worlds of experience and lends itself to interdisciplinary approaches. To a certain degree, it also subverts any differentiation between the linguistic and pictorial signs and challenges the notion of a self-sufficient text. As in the case of other illustrated manuscripts of the Molon Toyin’s tale, here, too, the author’s or illustrator’s main concern is to illustrate the workings of karma and its results, expressing them in compelling, pictorial terms. At the same time, illustrations also function both as visual memory aids and as the means of aesthetic gratification. Due to the anonymity of the manuscript examined in this article, it is difficult to determine with any certainty whether the orthography and graphic features of the manuscript’s illustrations are conditioned by the scribe, who is most likely also an illustrator, by his monastic training and the place where he received it, or by the expectations of the patron who commissioned the manuscript. -

THREE PRAYER TEXTS by ÖNDÖR GEGEEN ZANABAZAR Zsuzsa

THREE PRAYER TEXTS BY ÖNDÖR GEGEEN ZANABAZAR Zsuzsa Majer Introduction A study of the activities as a head of Mongolian Buddhism and the works of Öndör Gegeen Zanabazar (1635-1723), the first head of Mongolia Buddhism, has been the topic of numerous books and articles written in Mongolia.i A ceremony commemorating Zanabazar’s death is regularly held in every Mongolian temple on the fourteenth day of the first month of spring, which is known as the “Great Day of Öndör Gegeen” (Öndör gegeenii ikh düitsen ödör, Tib. dus chen). As it coincides with the fourteenth day of the ceremonies of the Lunar New Year, on that day, a double ceremony called the “Two-fold Prayer” (Davkhar yerööl) is held. Before looking at prayers composed by Zanabazar included in this chapter, let us first give a short description of Zanabazar’s activities in general, and then examine the circumstances and background to the composition of his prayers and their usage in the ceremonial system in the pre-socialist Mongolia and today. ii No account of the ceremonial texts written by Zanabazar is known in English or in any other European language.iii A brief discussion on the usage of these texts in the ceremonial system, the recommendations of having them recited, and the background information to the ceremonial system of Mongolian Buddhism are all based on the field research carried out by the author of this chapter. All three prayers translated in this chapter were composed in the Tibetan language. The first included in this chapter remains the most important prayer in the daily practice of Mongolian Buddhists, thus, being the main prayer in Mongolian Buddhism in general, in which the texts of different Tibetan Buddhist traditions and lineages are ortherwise used. -

Central Asian Sources and Central Asian Research

n October 2014 about thirty scholars from Asia and Europe came together for a conference to discuss different kinds of sources for the research on ICentral Asia. From museum collections and ancient manuscripts to modern newspapers and pulp fi ction and the wind horses fl ying against the blue sky of Mongolia there was a wide range of topics. Modern data processing and Göttinger data management and the problems of handling fi ve different languages and Bibliotheksschriften scripts for a dictionary project were leading us into the modern digital age. The Band 39 dominating theme of the whole conference was the importance of collections of source material found in libraries and archives, their preservation and expansion for future generations of scholars. Some of the fi nest presentations were selected for this volume and are now published for a wider audience. Central Asian Sources and Central Asian Research edited by Johannes Reckel Central Asian Sources and Research ISBN: 978-3-86395-272-3 ISSN: 0943-951X Universitätsverlag Göttingen Universitätsverlag Göttingen Johannes Reckel (ed.) Central Asian Sources and Central Asian Research This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Published as Volume 39 of the series “Göttinger Bibliotheksschriften” by Universitätsverlag Göttingen 2016 Johannes Reckel (ed.) Central Asian Sources and Central Asian Research Selected Proceedings from the International Symposium “Central Asian Sources and Central Asian Research”, October 23rd–26th, 2014 at Göttingen State and University Library Göttinger Bibliotheksschriften Volume 39 Universitätsverlag Göttingen 2016 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. -

Table of Contents

THE WRITINGS OF GENERAL LU: RELIGION AND RULE IN KHALKHA MONGOLIA AT THE TURN OF THE 20TH CENTURY Alice W. Seddon Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of Central Eurasian Studies, Indiana University November 2009 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Master’s Thesis Committee Christopher P. Atwood, Ph.D. György Kara, Ph.D. Elliot Sperling, Ph.D. ii © 2009 Alice W. Seddon ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………..1 Part 1: Journal…………………………………………………………………………...14 BT 26, autumn…………………………………………………………………...15 BT 27…………………………………………………………………………….18 BT 27, summer…………………………………………………………………..18 BT 28, spring…………………………………………………………………….19 BT 29, autumn…………………………………………………………………...20 BT 29, winter…………………………………………………………………….21 BT 30, summer…………………………………………………………………..22 BT 30, autumn…………………………………………………………………...24 BT 31…………………………………………………………………………….24 BT 31, spring…………………………………………………………………….24 BT 31, spring…………………………………………………………………….26 Part 2: Praise for Khankhökhii……………………………………………...…………...32 Part 3……………………………………………………………………….…………….46 Poems…………………………………………………………………………….47 North of the High Holy One (version A)…………………………………..47 North of the High Holy One (version B)…………………………………..49 The Hunt…………………………………………………………………...50 The Way of This World…………………………………………………....51 Why Carry a Tune…………………………………………………………51 -

31 Literature in Turkic and Mongolian

ISBN 92-3-103985-7 LITERATURE IN TURKIC 31 LITERATURE IN TURKIC AND MONGOLIAN R. Dor and G. Kara Contents LITERATURE IN TURKIC .............................. 888 Urban literature ..................................... 889 The literature of the steppe and mountains ....................... 893 Conclusion ....................................... 896 LITERATURE IN MONGOLIAN ........................... 897 Inner Mongolia and Dzungaria ............................. 907 Kalmukia ........................................ 909 Buriatia ......................................... 910 Part One LITERATURE IN TURKIC (R. Dor) The Turkish word literatür has bureaucratic connotations. It conjures up an image of great heaps and drifts of paper, instructions, memoranda, working papers and much more 888 ISBN 92-3-103985-7 Urban literature of the like, none of it of any conceivable relevance, none of it of any further use or any lasting interest. The purpose of this preliminary remark is to illustrate the vast conceptual distance separating us from anything that can reasonably be referred to as ‘the Turkic literature of Central Asia’. If, indeed, such a concept is graspable at all, for it seems highly unlikely that literature as such can ever be intuitively understood in its full extension, as it were encapsulated, at any particular moment. In the geographic region that is the subject of our present concern, however, there is a word that summarizes and defines literature in the conventional sense, and that is adabiyat¯ . Adabiyat¯ originally denoted a practical standard of conduct, one that was doubly resonant in that it purported simultaneously to inculcate virtue and to have been handed down from previous generations. The Turkic literature of Central Asia is thus primarily a form of humanitas, i.e. a sum of knowledge that imparts urbanity and courteous behaviour to the individual. -

MEMORY of the WORLD REGISTER Mongolian Tanjur

MEMORY OF THE WORLD REGISTER Mongolian Tanjur (Mongolia) Ref N° 2010-48 PART A – ESSENTIAL INFORMATION 1 SUMMARY Tanjur is a Tibetan word which means translation of treatise. These had a huge effect on the development of Mongolian literature and other branch sciences. This is the greatest sutra written on thick Chinese muutuu paper with red nature dust paint size 22.7 x 71,8 cm and which has 107839 pages. It is a large collection of over 3427 works on ten great and small sciences (philosophy, technology, logic, medicine, philology, astrology, model dance, poetics, Abhidarma, composition) created by ancient Indian and Tibetan scientists and panditas. The Mongolian dust paint printed Tanjur had been translated from Tibetan into Mongolian by over 200 translators under the supervision of reincarnates Janjaa Rolbiidorj and Shireet Luvsandambiinyam between 1741 and 1742 and had been printed in Beijing between 1742and 1749. To print Mongolian Tanjur from blocks 2160.9 ounce of silver was used. It means that one collection’s cost equaled to 4000 sheep’s total cost of that time. 2 DETAILS OF THE NOMINATOR 2.1 Name (person or organisation) Dorjbal DALAIJARGAL 2.2 Relationship to the documentary heritage nominated Chairperson of the Mongolian National Committee for Memory of the World Program 2.3 Contact person (s) Dorjbal DALAIJARGAL Secretary - General of the Mongolian National Commission for UNESCO, Chairperson of the Mongolian National Committee for Memory of the World Program 2.4 Contact details (include address, phone, fax, email) Address: Government building XI Post office – 38 Revolution Avenue, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia Tel: (976)-11-315652 (976)-99110163 Fax: (976)-11-315652 3 IDENTITY AND DESCRIPTION OF THE DOCUMENTARY HERITAGE 3.1 Name and identification details of the items being nominated • Mongolian Tanjur Location : National Library of Mongolia Ulaanbaatar - 210648, Chinggis avenue - 4 Fax: 976-11-323100, Tel: 976-11-323100, Web site: http//www.nationallibrary.mn 3.2 Description MONGOLIAN TANJUR AUTHOR: Collective work DATE OF CREATION: Between 1742 and 1749. -

Dad Resume 2012

Tsogtsaikhan Mijid /Tsogo/ 7474 East Arkansas Avenue Denver, CO, 80231 Ph. 303-338-8344 [email protected] http://www.tsogoart.com born 1965 in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia lives Denver, Colorado education 1984 - 1990 Master of Fine Arts in Graphic Arts, Shevchenko Art Academy of Ukraine, Kiev, Ukraine 1981 - 1984 Bachelor of Fine Arts in Traditional Mongolian Arts, Mongolian University of Art and Culture, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia exhibition history solo (fine art) 2011 Migration, Pirate Contemporary Art Gallery, Denver, CO 2010 Nomadic Spirits, Pirate Contemporary Art Gallery, Denver, CO 2010 Traditional Mongolian Paintings, Bd's Mongolian Barbecue, Denver, CO 2009 Angels, Pirate Contemporary Art Gallery, Denver, CO 2009 - 2010 Paris on the Platte Cafe, Denver, CO 2009 Bd's Mongolian Grill, Burnsville, MN 2009 The Thin Man Bar, Denver, CO 2009 Mongolian Traditional Arts, Governor's Residence Boettcher Mansion, Denver, CO 2009 Dazzle Jazz Bar, Denver, CO 2008 - 2009 (Selected Exhibitions), UB Bar, Denver, CO 2008 Pirate Contemporary Art Gallery, Denver, CO 2007 Revelation, Pirate Contemporary Art Gallery, Denver, CO 2007 Sunny Days, La Junta Technical University, La Junta, CO 2006 Shadows, Pirate Contemporary Art Gallery, Denver, CO 2005 Pirate Contemporary Art Gallery, Denver, CO 2005 The Thin Man Bar, Denver, CO 2005 - 2012 (Selected Exhibitions), Bd's Mongolian Barbecue, Denver, CO 2004 University of Colorado-Center for Visual Arts 2004 - 2007 (Selected Exhibitions), Naadam Colorado Mongolian Outdoor Festival, CO 2004 Two Weeks Before and After -

The Mongolian Language in Education in the People's Republic Of

The Mongolian language in education in the People’s Republic of China European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning hosted by MONGOLIAN The Mongolian language in education in the People’s Republic of China c/o Fryske Akademy Doelestrjitte 8 P.O. Box 54 NL-8900 AB Ljouwert/Leeuwarden The Netherlands T 0031 (0) 58 - 234 3027 W www.mercator-research.eu E [email protected] | Regional dossiers series | tca r cum n n i- ual e : Available in this series: This document was published by the Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism Hungarian; the Hungarian language in education in Romania and Language Learning with financial support from the Fryske Akademy and the Province Hungarian; the Hungarian language in education in Slovakia of Fryslân. Hungarian; the Hungarian language in education in Slovenia Hungarian; the Hungarian language in education in Ukraine Irish; the Irish language in education in Northern Ireland (3rd ed.) Irish; the Irish language in education in the Republic of Ireland (2nd ed.) © Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism Italian; the Italian language in education in Slovenia and Language Learning, 2019 Kashubian; the Kashubian language in education in Poland Irish; the Irish language in education in Northern Ireland (3rd ed.) ISSN: 1570 – 1239 Irish; the Irish language in education in the Republic of Ireland (2nd ed.) 1st edition Italian; the Italian language in education in Slovenia Kashubian; the Kashubian language in education in Poland The contents of this dossier may be reproduced in print, except for commercial purposes, Ladin; the Ladin language in education in Italy (2nd ed.) provided that the extract is proceeded by a complete reference to the Mercator European Latgalian; the Latgalian language in education in Latvia Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning. -

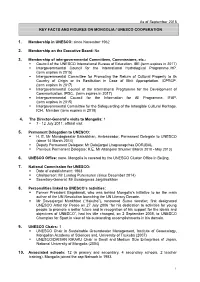

As of September 2015 KEY FACTS and FIGURES on MONGOLIA / UNESCO COOPERATION Membership in UNESCO: Since November 1962 Membership

As of September 2015 KEY FACTS AND FIGURES ON MONGOLIA / UNESCO COOPERATION 1. Membership in UNESCO: since November 1962 2. Membership on the Executive Board: No 3. Membership of intergovernmental Committees, Commissions, etc.: . Council of the UNESCO International Bureau of Education. IBE.(term expires in 2017) . Intergovernmental Council for the International Hydrological Programme.IHP. (term expires in 2015) . Intergovernmental Committee for Promoting the Return of Cultural Property to its Country of Origin or its Restitution in Case of Illicit Appropriation. ICPRCP. (term expires in 2017) . Intergovernmental Council of the International Programme for the Development of Communication. IPDC. (term expires in 2017) . Intergovernmental Council for the Information for All Programme. IFAP. (term expires in 2015) . Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. ICH. Member (term expires in 2018) 4. The Director-General’s visits to Mongolia: 1 . 7 - 12 July 2011: official visit 5. Permanent Delegation to UNESCO: . H. E. Mr Mundagbaatar Batsaikhan, Ambassador, Permanent Delegate to UNESCO (since 14 March 2014) . Deputy Permanent Delegate: Mr Dalaijargal Lhagvaragchaa DORJBAL . Previous Permanent Delegate: H.E. Mr Altangerel Shukher (March 2010 - May 2013) 6. UNESCO Office: none. Mongolia is covered by the UNESCO Cluster Office in Beijing. 7. National Commission for UNESCO: . Date of establishment: 1963 . Chairperson: Mr Lundeg Purevsuren (since December 2014) . Secretary-General: Mr Gundegmaa Jargalsaikhan