Rethinking Royal Navy Signal Reform During the American War of Independence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TA22 Catalog Session Vb Medals.Indd

e Admiral Vernon Medals of 1739 and 1741 by Daniel Frank Sedwick If the heart of collecting is visual and intellectual stimulation mixed with historical study, then the “Admiral Vernon” medals crafted in England in the period 1739-1741 are the perfect collectibles. e sheer number of di erent varieties of these medals makes collecting them both challenging and feasible. Fascination with these historic pieces has spawned more than a dozen studies over the past 180+ years, culminating in the book Medallic Portraits of Admiral Vernon (2010), by John Adams and Fernando Chao (the “AC” reference we quote in our lot descriptions). With this well-illustrated book alone, one can spend many enjoyable hours attributing each piece down to exact die details. e biggest challenge with these medals is condition, as they were heavily used and abused, which makes the present o ering comprising the collection of Richard Stuart an exceptional opportunity. e con! ict began with the capture and torture of the British merchant ship captain Robert Jenkins by the Spanish o Havana, Cuba, in 1731. His alleged punishment for smuggling was the removal of one of his ears, which he physically produced for British Parliament in 1739, setting o what became known as the “War of Jenkins’ Ear” starting that year, e ectively “Great Britain’s " rst protracted naval war in the Americas.” 1 In a burst of vengeful braggadocio, the experienced British admiral Edward Vernon reportedly said he could take the Spanish port of Portobelo, Panama, “with six ships only,” the larger goal being to disrupt the ! ow of Spanish shipping of treasure from the New World. -

Spanish, French, Dutch, Andamerican Patriots of Thb West Indies During

Spanish, French, Dutch, andAmerican Patriots of thb West Indies i# During the AMERICAN Revolution PART7 SPANISH BORDERLAND STUDIES By Granvil~ W. andN. C. Hough -~ ,~~~.'.i~:~ " :~, ~i " .... - ~ ,~ ~"~" ..... "~,~~'~~'-~ ,%v t-5.._. / © Copyright ,i. "; 2001 ~(1 ~,'~': .i: • by '!!|fi:l~: r!;.~:! Granville W. and N. C. Hough 3438 Bahia Blanca West, Apt B ~.l.-c • Laguna Hills, CA 92653-2830 !LI.'.. Email: gwhough(~earthiink.net u~ "~: .. ' ?-' ,, i.. Other books in this series include: • ...~ , Svain's California Patriots in its 1779-1783 War with England - During the.American Revolution, Part 1, 1998. ,. Sp~fin's Califomi0 Patriqts in its 1779-1783 Wor with Englgnd - During the American Revolution, Part 2, :999. Spain's Arizona Patriots in ire |779-1783 War with Engl~n~i - During the Amcricgn RevolutiQn, Third Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Svaln's New Mexico Patriots in its 1779-|783 Wit" wi~ England- During the American Revolution, Fourth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Spain's Texa~ patriot~ in its 1779-1783 War with Enaland - Daring the A~a~ri~n Revolution, Fifth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 2000. Spain's Louisi~a Patriots in its; 1779-1783 War witil England - During.the American Revolution, Sixth StUdy of the Spanish Borderlands, 20(~0. ./ / . Svain's Patriots of Northerrt New Svain - From South of the U. S. Border - in its 1779- 1783 War with Engl~nd_ Eighth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, coming soon. ,:.Z ~JI ,. Published by: SHHAK PRESS ~'~"'. ~ ~i~: :~ .~:,: .. Society of Hispanic Historical and Ancestral Research ~.,~.,:" P.O. Box 490 Midway City, CA 92655-0490 (714) 894-8161 ~, ~)it.,I ,. -

Proquest Dissertations

00180 UNIVERS1TE DOTTAWA ECOLE DES GRADUES M.A., (History) BISUOTHEQUES f . \6g^ f £, L.OKAKItS «, The Expeditionary Force Designed for the West Indies, 1714-0 by J. Lawrence Fisher. DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa 1970 UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES UMI Number: EC55425 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform EC55425 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 UNIVERSITE D'OTTAWA ECOLE DES GRADUES Acknowledgements This thesis was prepared under the direction of Professor Julian Gwyn, M.A., B.Litt., of the History Department of the University of Ottawa. It was he who suggested naval administration during the eighteenth century as a verdant field for research. I am particularly indebted to hira for his guidance, encouragement, and careful criticism. I am also indebted to Mr. Paul Kavanagh, who read parts of this draft, and Mr. William E. Clarke who drew the two maps. UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES UNIVERSITE DOTTAWA ECOLE DES GRADUES Contents I. -

Oxford Book Fair List 2014

BERNARD QUARITCH LTD OXFORD BOOK FAIR LIST including NEW ACQUISITIONS ● APRIL 2014 Main Hall, Oxford Brookes University (Headington Hill Campus) Gipsy Lane, Oxford OX3 0BP Stand 87 Saturday 26th April 12 noon – 6pm - & - Sunday 27th April 10am – 4pm A MEMOIR OF JOHN ADAM, PRESENTED TO THE FORMER PRIME MINISTER LORD GRENVILLE BY WILLIAM ADAM 1. [ADAM, William (editor).] Description and Representation of the Mural Monument, Erected in the Cathedral of Calcutta, by General Subscription, to the Memory of John Adam, Designed and Executed by Richard Westmacott, R.A. [?Edinburgh, ?William Adam, circa 1830]. 4to (262 x 203mm), pp. [4 (blank ll.)], [1]-2 (‘Address of the British Inhabitants of Calcutta, to John Adam, on his Embarking for England in March 1825’), [2 (contents, verso blank)], [2 (blank l.)], [2 (title, verso blank)], [1]-2 (‘Description of the Monument’), [2 (‘Inscription on the Base of the Tomb’, verso blank)], [2 (‘Translation of Claudian’)], [1 (‘Extract of a Letter from … Reginald Heber … to … Charles Williams Wynn’)], [2 (‘Extract from a Sermon of Bishop Heber, Preached at Calcutta on Christmas Day, 1825’)], [1 (blank)]; mounted engraved plate on india by J. Horsburgh after Westmacott, retaining tissue guard; some light spotting, a little heavier on plate; contemporary straight-grained [?Scottish] black morocco [?for Adam for presentation], endpapers watermarked 1829, boards with broad borders of palmette and flower-and-thistle rolls, upper board lettered in blind ‘Monument to John Adam Erected at Calcutta 1827’, turn-ins roll-tooled in blind, mustard-yellow endpapers, all edges gilt; slightly rubbed and scuffed, otherwise very good; provenance: William Wyndham Grenville, Baron Grenville, 3 March 1830 (1759-1834, autograph presentation inscription from William Adam on preliminary blank and tipped-in autograph letter signed from Adam to Grenville, Edinburgh, 6 March 1830, 3pp on a bifolium, addressed on final page). -

Henry Clinton Papers, Volume Descriptions

Henry Clinton Papers William L. Clements Library Volume Descriptions The University of Michigan Finding Aid: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/c/clementsead/umich-wcl-M-42cli?view=text Major Themes and Events in the Volumes of the Chronological Series of the Henry Clinton papers Volume 1 1736-1763 • Death of George Clinton and distribution of estate • Henry Clinton's property in North America • Clinton's account of his actions in Seven Years War including his wounding at the Battle of Friedberg Volume 2 1764-1766 • Dispersal of George Clinton estate • Mary Dunckerley's account of bearing Thomas Dunckerley, illegitimate child of King George II • Clinton promoted to colonel of 12th Regiment of Foot • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot Volume 3 January 1-July 23, 1767 • Clinton's marriage to Harriet Carter • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Clinton's property in North America Volume 4 August 14, 1767-[1767] • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Relations between British and Cherokee Indians • Death of Anne (Carle) Clinton and distribution of her estate Volume 5 January 3, 1768-[1768] • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Clinton discusses military tactics • Finances of Mary (Clinton) Willes, sister of Henry Clinton Volume 6 January 3, 1768-[1769] • Birth of Augusta Clinton • Henry Clinton's finances and property in North America Volume 7 January 9, 1770-[1771] • Matters concerning the 12th Regiment of Foot • Inventory of Clinton's possessions • William Henry Clinton born • Inspection of ports Volume 8 January 9, 1772-May -

An Ear, a Man from Gipuzkoa in the Basque Country and 190 Boats

AN EAR, A MAN FROM GIPUZKOA IN THE BASQUE COUNTRY AND 190 BOATS Monthly Strategy Report January 2014 Alejandro Vidal Head of Market Strategy G & FI IN NA K N N C A BEST E B ASSET & R L WEALTH E A V B MANAGEMENT I E O SPAIN W L 2013 G A S W A R D Monthly Strategy Report. January 2014 An ear, a man from Gipuzkoa in the Basque Country and 190 boats. We all know that military interests are tightly bound to economic interests. We are equally aware that Spain has a military past in which defeats stand out and the victories are relatively few. Here is a story that allowed the push that the colonies gave to the Spanish economy to be maintained and which facilitated the independence of the United States. In 1738, with the War of the Spanish Succession at an end, it was now obvious that the Spanish Empire was fi nding it increasingly diffi cult to jointly maintain trade and defend the Latin American strongholds, especially in the Caribbean. Bouts of piracy and smuggling were becoming more frequent and were urged by the King of England, who looked at it as an undeclared war of attrition against the Bourbons, his main enemies who now occupied both the French and Spanish throne. However, given the Spanish weakness in the area was more and more evident, the feeling in the Caribbean was ripe with pre-war tension with pirates and English corsairs placing increasing pressure on the merchants fl ying the Spanish fl ag. -

The Colours of the Fleet

THE COLOURS OF THE FLEET TCOF BRITISH & BRITISH DERIVED ENSIGNS ~ THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE WORLDWIDE LIST OF ALL FLAGS AND ENSIGNS, PAST AND PRESENT, WHICH BEAR THE UNION FLAG IN THE CANTON “Build up the highway clear it of stones lift up an ensign over the peoples” Isaiah 62 vv 10 Created and compiled by Malcolm Farrow OBE President of the Flag Institute Edited and updated by David Prothero 15 January 2015 © 1 CONTENTS Chapter 1 Page 3 Introduction Page 5 Definition of an Ensign Page 6 The Development of Modern Ensigns Page 10 Union Flags, Flagstaffs and Crowns Page 13 A Brief Summary Page 13 Reference Sources Page 14 Chronology Page 17 Numerical Summary of Ensigns Chapter 2 British Ensigns and Related Flags in Current Use Page 18 White Ensigns Page 25 Blue Ensigns Page 37 Red Ensigns Page 42 Sky Blue Ensigns Page 43 Ensigns of Other Colours Page 45 Old Flags in Current Use Chapter 3 Special Ensigns of Yacht Clubs and Sailing Associations Page 48 Introduction Page 50 Current Page 62 Obsolete Chapter 4 Obsolete Ensigns and Related Flags Page 68 British Isles Page 81 Commonwealth and Empire Page 112 Unidentified Flags Page 112 Hypothetical Flags Chapter 5 Exclusions. Page 114 Flags similar to Ensigns and Unofficial Ensigns Chapter 6 Proclamations Page 121 A Proclamation Amending Proclamation dated 1st January 1801 declaring what Ensign or Colours shall be borne at sea by Merchant Ships. Page 122 Proclamation dated January 1, 1801 declaring what ensign or colours shall be borne at sea by merchant ships. 2 CHAPTER 1 Introduction The Colours of The Fleet 2013 attempts to fill a gap in the constitutional and historic records of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth by seeking to list all British and British derived ensigns which have ever existed. -

17 Pirates.Cdr

8301EdwardEngland,originunknown, Pirates’ flags (JollyRoger)ofthe17thcenturypiracy. wasstrandedinMadagaskar1720 byJohn Tayloranddiedthere Someofthepirateshadsmallfleetsofships shorttimelaterasapoorman. thatsailedundertheseflags. Lk=18mm=1,80 € apiece Afterasuccessfulcounteractionbymanycountries Lk=28mm=2,20 € apiece thiskindofpiracyabatedafter1722. Lk=38mm=3,60 € apiece Lk=80mm=6,50 € apiece 8303JackRackam(CalicoJack), wasimprisonedtogetherwith 8302HenryEvery, theamazones AnneBonnyand bornaround1653,wascalledlater MaryRead.Washangedin1720. BenjaminBridgeman,wasnevercaught Lk=18mm=1,80 € apiece anddiedinthefirstquarter Lk=28mm=2,20 € apiece of18thcenturysomewhereinEngland. Lk=38mm=3,20 € apiece Lk=18mm=1,80 € apiece Lk=45mm=3,80 € apiece Lk=28mm=2,20 € apiece Lk=50mm=4,20 € apiece Lk=38mm=3,20 € apiece 8305 Thomas Tew, piratewithaprivateeringcommision fromthegovernorofBermuda, 8304RichardWorley, hedied1695inafightwhile littleisknownabouthim. boardinganIndianmerchantship. Lk=18mm=1,80 € apiece Lk=18mm=1,80 € apiece Lk=28mm=2,20 € apiece Lk=28mm=2,20 € apiece Lk=38mm=3,20 € apiece Lk=38mm=3,20 € apiece Lk=70mm=5,60 € apiece 8306ChristopherCondent, hecapturedahuge Arabshipwitharealtreasure in1719nearBombay. Asaresultheandmostof hiscrewgaveuppiracyandnegotiatedapardon withtheFrenchgovernorofReunion.Condent marriedthegovernor’ssisterinlawandlater 8307Edward Teach,namedBlackbeard, settledaswelltodoshipownerinFrance. oneofthemostfearedpiratesofhistime. Lk=15mm=1,90 € apiece Hediedin1718inagunfight Lk=18mm=2,25 € apiece duringhiscapture. Lk=28mm=2,60 -

11 February 1992.Pdf

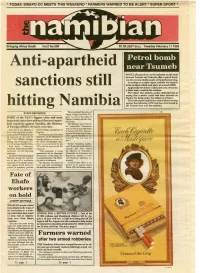

* TODAY: SWAPO CC MEE"FS THIS WEEKEND * FARMERS WARNED TO, BE AlERT * SUPER SPORT * c • Bringing Africa South Vol.2 No.500 R1.00 (GST Inc.) Tuesday February 111992 AIl ti -apartheid REGULAR patrols are to be instituted on the road between Tsumeb and Oshivelo after a petrol bomb was thrown at a minibus early on Saturday morning. , Accor ding to a radio report, nobody was injured sanctions still in the incident which took place at around 02hOO. Apparently two motor cyclists and a car, driven by a white man, overtook the minibus. The report also quoted a police spokesperson as saying that a motor cyclist had been arrested on Sunday for being under the influence of liquor. The radio report said further that leaflets warning against the rightwing A WB had been distributed in hitting Namibia the Tsumeb area over the weekend. These included the states of ~--------~================-, === STAFF REPORTER Maine, Oregon and West Vir - SOME of the USA's biggest cities and most ginia, as well as the cities of Denver, Colorado and Palo Alto, important states have still not lifted anti-apart California. heid sanctions against Namibia, the Ministry The Ministry noted'that af of Foreign Affairs revealed yesterday. ter "constructive" discussions with the Maryland authorities Included in the Ministry's and its illegal occupation of in January this year, the pass list of city and state govern Namibia. ing of a bill removing all sanc ments in the US that have kept The Ministry said one of the tions against Namibia is ex up sanctions are the cities of objectives of the Ministry of ' pected in "the very near fu New York, Miami, Atlanta, Foreign Affairs is to point out ture". -

Captains of Hms Ajax 1 John Carter Allen

CAPTAINS OF HMS AJAX 1 JOHN CARTER ALLEN: CAPTAIN OF HMS AJAX from 27 MAY 1770 to 6 JUNE 1771 and from JUNE to 23 AUGUST 1779 John Carter Allen was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant on 14 June 1745 and to that of Commander on 15 April 1757. He was appointed to the Grampus sloop in command, and towards the end of the same year captured a large privateer. He was soon after posted to a large 6th-rate on the Mediterranean station. He was promoted to the rank of Post Captain on 21 March 1758, and appointed to the Experiment, but in August 1760, he was transferred to the Repulse frigate on the Halifax station, and took part, under Mr Byron, in the attack and destruction of three French frigates and a considerable number of small craft in Chalem Bay. The Repulse then joined the West India fleet, and continued on that station until the end of hostilities. In 1763 the Repulse was laid-up. John Allen did not hold any further commissions until May 1770, when he was appointed to the Ajax, 74. This was the ship's first commission, and she, together with the Ramillies, Defence, Centaur, and Rippon, 74's, embarked the 30th Regiment of Foot at Cork and transported them to Gibraltar. Soon after the Ajax was laid-up, and it was not until 1777 that Captain Allen was appointed to the Albion, and in the following year to the Egmont. When the Channel Fleet returned from Ushant, he once more assumed command of the Ajax, refitting at Portsmouth. -

Grosvenor Prints 19 Shelton Street Covent Garden London WC2H 9JN

Grosvenor Prints 19 Shelton Street Covent Garden London WC2H 9JN Tel: 020 7836 1979 Fax: 020 7379 6695 E-mail: [email protected] www.grosvenorprints.com Dealers in Antique Prints & Books Prints from the Collection of the Hon. Christopher Lennox-Boyd Arts 3801 [Little Fatima.] [Painted by Frederick, Lord Leighton.] Gerald 2566 Robinson Crusoe Reading the Bible to Robinson. London Published December 15th 1898 by his Man Friday. "During the long timer Arthur Lucas the Proprietor, 31 New Bond Street, W. Mezzotint, proof signed by the engraver, ltd to 275. that Friday had now been with me, and 310 x 490mm. £420 that he began to speak to me, and 'Little Fatima' has an added interest because of its understand me. I was not wanting to lay a Orientalism. Leighton first showed an Oriental subject, foundation of religious knowledge in his a `Reminiscence of Algiers' at the Society of British mind _ He listened with great attention." Artists in 1858. Ten years later, in 1868, he made a Painted by Alexr. Fraser. Engraved by Charles G. journey to Egypt and in the autumn of 1873 he worked Lewis. London, Published Octr. 15, 1836 by Henry in Damascus where he made many studies and where Graves & Co., Printsellers to the King, 6 Pall Mall. he probably gained the inspiration for the present work. vignette of a shipwreck in margin below image. Gerald Philip Robinson (printmaker; 1858 - Mixed-method, mezzotint with remarques showing the 1942)Mostly declared pirnts PSA. wreck of his ship. 640 x 515mm. Tears in bottom Printsellers:Vol.II: margins affecting the plate mark. -

Chronology of the American Revolution

INTRODUCTION One of the missions of The Friends of Valley Forge Park is the promotion of our historical heritage so that the spirit of what took place over two hundred years ago continues to inspire both current and future generations of all people. It is with great pleasure and satisfaction that we are able to offer to the public this chronology of events of The American Revolution. While a simple listing of facts, it is the hope that it will instill in some the desire to dig a little deeper into the fascinating stories underlying the events presented. The following pages were compiled over a three year period with text taken from many sources, including the internet, reference books, tapes and many other available resources. A bibliography of source material is listed at the end of the book. This publication is the result of the dedication, time and effort of Mr. Frank Resavy, a long time volunteer at Valley Forge National Historical Park and a member of The Friends of Valley Forge Park. As with most efforts of this magnitude, a little help from friends is invaluable. Frank and The Friends are enormously grateful for the generous support that he received from the staff and volunteers at Valley Forge National Park as well as the education committee of The Friends of Valley Forge Park. Don R Naimoli Chairman The Friends of Valley Forge Park ************** The Friends of Valley Forge Park, through and with its members, seeks to: Preserve…the past Conserve…for the future Enjoy…today Please join with us and help share in the stewardship of Valley Forge National Park.