Policing the Planet: Why the Policing Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Rowson Phd Thesis Politics and Putinism a Critical Examination

Politics and Putinism: A Critical Examination of New Russian Drama James Rowson A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Royal Holloway, University of London Department of Drama, Theatre & Dance September 2017 1 Declaration of Authorship I James Rowson hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: ______________________ Date: ________________________ 2 Abstract This thesis will contextualise and critically explore how New Drama (Novaya Drama) has been shaped by and adapted to the political, social, and cultural landscape under Putinism (from 2000). It draws on close analysis of a variety of plays written by a burgeoning collection of playwrights from across Russia, examining how this provocative and political artistic movement has emerged as one of the most vehement critics of the Putin regime. This study argues that the manifold New Drama repertoire addresses key facets of Putinism by performing suppressed and marginalised voices in public arenas. It contends that New Drama has challenged the established, normative discourses of Putinism presented in the Russian media and by Putin himself, and demonstrates how these productions have situated themselves in the context of the nascent opposition movement in Russia. By doing so, this thesis will offer a fresh perspective on how New Drama’s precarious engagement with Putinism provokes political debate in contemporary Russia, and challenges audience members to consider their own role in Putin’s autocracy. The first chapter surveys the theatrical and political landscape in Russia at the turn of the millennium, focusing on the political and historical contexts of New Drama in Russian theatre and culture. -

In Ta-Nehisi Coates's Between the World and Me

“OVERPOLICED AND UNDERPROTECTED”:1 RACIALIZED GENDERED VIOLENCE(S) IN TA-NEHISI COATES’S BETWEEN THE WORLD AND ME “SOBREVIGILADAS Y DESPROTEGIDAS”: VIOLENCIA(S) DE GÉNERO RACIALIZADA(S) EN BETWEEN THE WORLD AND ME, DE TA-NEHISI COATES EVA PUYUELO UREÑA Universidad de Barcelona [email protected] 13 Abstract Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me (2015) evidences the lack of visibility of black women in discourses on racial profiling. Far from tracing a complete representation of the dimensions of racism, Coates presents a masculinized portrayal of its victims, relegating black women to liminal positions even though they are one of the most overpoliced groups in US society, and disregarding the fact that they are also subject to other forms of harassment, such as sexual fondling and other forms of abusive frisking. In the face of this situation, many women have struggled, both from an academic and a political-activist angle, to raise the visibility of the role of black women in contemporary discourses on racism. Keywords: police brutality, racism, gender, silencing, black women. Resumen Con la publicación de la obra de Ta-Nehisi Coates Between the World and Me (2015) se puso de manifiesto un problema que hacía tiempo acechaba a los discursos sobre racismo institucional: ¿dónde estaban las mujeres de color? Lejos de trazar un esbozo fiel de las dimensiones de la discriminación racial, la obra de Coates aboga por una representación masculinizada de las víctimas, relegando a las miscelánea: a journal of english and american studies 62 (2020): pp. 13-28 ISSN: 1137-6368 Eva Puyuelo Ureña mujeres a posiciones marginales y obviando formas de acoso que ellas, a diferencia de los hombres, son más propensas a experimentar. -

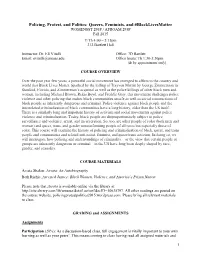

Policing, Protest, and Politics Syllabus

Policing, Protest, and Politics: Queers, Feminists, and #BlackLivesMatter WOMENSST 295P / AFROAM 295P Fall 2015 T/Th 4:00 – 5:15pm 212 Bartlett Hall Instructor: Dr. Eli Vitulli Office: 7D Bartlett Email: [email protected] Office hours: Th 1:30-3:30pm (& by appointment only) COURSE OVERVIEW Over the past year few years, a powerful social movement has emerged to affirm to the country and world that Black Lives Matter. Sparked by the killing of Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman in Stanford, Florida, and Zimmerman’s acquittal as well as the police killings of other black men and women, including Michael Brown, Rekia Boyd, and Freddie Gray, this movement challenges police violence and other policing that makes black communities unsafe as well as social constructions of black people as inherently dangerous and criminal. Police violence against black people and the interrelated criminalization of black communities have a long history, older than the US itself. There is a similarly long and important history of activism and social movements against police violence and criminalization. Today, black people are disproportionately subject to police surveillance and violence, arrest, and incarceration. So, too, are other people of color (both men and women) and queer, trans, and gender nonconforming people of all races but especially those of color. This course will examine the history of policing and criminalization of black, queer, and trans people and communities and related anti-racist, feminist, and queer/trans activism. In doing so, we will interrogate how policing and understandings of criminality—or the view that certain people or groups are inherently dangerous or criminal—in the US have long been deeply shaped by race, gender, and sexuality. -

ALEX DELGADO Production Designer

ALEX DELGADO Production Designer PROJECTS DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS THE KEYS OF CHRISTMAS David Meyers YouTube Red Feature OPENING NIGHTS Isaac Rentz Dark Factory Entertainment Feature Los Angeles Film Festival G.U.Y. Lady Gaga Rocket In My Pocket / Riveting Short Film Entertainment MR. HAPPY Colin Tilley Vice Short Film COMMERCIALS & MUSIC VIDEOS SOL Republic Headphones, Kraken Rum, Fox Sports, Wendy’s, Corona, Xbox, Optimum, Comcast, Delta Airlines, Samsung, Hasbro, SONOS, Reebok, Veria Living, Dropbox, Walmart, Adidas, Go Daddy, Microsoft, Sony, Boomchickapop Popcorn, Macy’s Taco Bell, TGI Friday’s, Puma, ESPN, JCPenney, Infiniti, Nicki Minaj’s Pink Friday Perfume, ARI by Ariana Grande; Nicki Minaj - “The Boys ft. Cassie”, Lil’ Wayne - “Love Me ft. Drake & Future”, BOB “Out of My Mind ft. Nicki Minaj”, Fergie - “M.I.L.F.$”, Mike Posner - “I Took A Pill in Ibiza”, DJ Snake ft. Bipolar Sunshine - “Middle”, Mark Ronson - “Uptown Funk”, Kelly Clarkson - “People Like Us”, Flo Rida - “Sweet Spot ft. Jennifer Lopez”, Chris Brown - “Fine China”, Kelly Rowland - “Kisses Down Low”, Mika - “Popular”, 3OH!3 - “Back to Life”, Margaret - “Thank You Very Much”, The Lonely Island - “YOLO ft. Adam Levine & Kendrick Lamar”, David Guetta “Just One Last Time”, Nicki Minaj - “I Am Your Leader”, David Guetta - “I Can Only Imagine ft. Chris Brown & Lil’ Wayne”, Flying Lotus - “Tiny Tortures”, Nicki Minaj - “Freedom”, Labrinth - “Last Time”, Chris Brown - “She Ain’t You”, Chris Brown - “Next To You ft. Justin Bieber”, French Montana - “Shot Caller ft. Diddy and Rick Ross”, Aura Dione - “Friends ft. Rock Mafia”, Common - “Blue Sky”, Game - “Red Nation ft. Lil’ Wayne”, Tyga “Faded ft. -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

The Right to Privacy and the Future of Mass Surveillance’

‘The Right to Privacy and the Future of Mass Surveillance’ ABSTRACT This article considers the feasibility of the adoption by the Council of Europe Member States of a multilateral binding treaty, called the Intelligence Codex (the Codex), aimed at regulating the working methods of state intelligence agencies. The Codex is the result of deep concerns about mass surveillance practices conducted by the United States’ National Security Agency (NSA) and the United Kingdom Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ). The article explores the reasons for such a treaty. To that end, it identifies the discriminatory nature of the United States’ and the United Kingdom’s domestic legislation, pursuant to which foreign cyber surveillance programmes are operated, which reinforces the need to broaden the scope of extraterritorial application of the human rights treaties. Furthermore, it demonstrates that the US and UK foreign mass surveillance se practices interferes with the right to privacy of communications and cannot be justified under Article 17 ICCPR and Article 8 ECHR. As mass surveillance seems set to continue unabated, the article supports the calls from the Council of Europe to ban cyber espionage and mass untargeted cyber surveillance. The response to the proposal of a legally binding Intelligence Codexhard law solution to mass surveillance problem from the 47 Council of Europe governments has been so far muted, however a soft law option may be a viable way forward. Key Words: privacy, cyber surveillance, non-discrimination, Intelligence Codex, soft law. Introduction Peacetime espionage is by no means a new phenomenon in international relations.1 It has always been a prevalent method of gathering intelligence from afar, including through electronic means.2 However, foreign cyber surveillance on the scale revealed by Edward Snowden performed by the United States National Security Agency (NSA), the United Kingdom Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) and their Five Eyes partners3 1 Geoffrey B. -

Golden Gulag

GOLDEN GULAG AMERICAN CROSSROADS EDITED BY EARL LEWIS, GEORGE LIPSITZ, PEGGY PASCOE, GEORGE SÁNCHEZ, AND DANA TAKAGI GOLDENGULAG PRISONS, SURPLUS, CRISIS, AND OPPOSITION IN GLOBALIZING CALIFORNIA RUTHWILSONGILMORE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY LOS ANGELES LONDON University of California Press, one of the most distinguished uni- versity presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and nat- ural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Founda- tion and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and insti- tutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2007 by The Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gilmore, Ruth Wilson, 1950–. Golden gulag : prisons, surplus, crisis, and opposition in globalizing California / Ruth Wilson Gilmore. p. cm—(American crossroads ; 21). Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn-13: 978-0-520-22256-4 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-520-22256-3 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn-13: 978-0-520-24201-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-520-24201-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Prisons—California. 2. Prisons—Economic aspects—California. 3. Imprisonment—California. 4. Criminal justice, Administration of—California. 5. Discrimination in criminal justice administration—California. 6. Minorities—California. 7. California—Economic conditions. I. Title. II. Series. HV9475.C2G73 2007 365'.9794—dc22 2006011674 Manufactured in the United States of America 15 14 13 12 111098765 This book is printed on New Leaf EcoBook 60, containing 60% postconsumer waste, processed chlorine free; 30% de-inked recycled fiber, elemental chlorine free; and 10% FSC-certified virgin fiber, to- tally chlorine free. -

A Failure of Intelligence: the Echelon Interception System & the Fundamental Right to Privacy in Europe

Pace International Law Review Volume 14 Issue 2 Fall 2002 Article 7 September 2002 Post-Sept. 11th International Surveillance Activity - A Failure of Intelligence: The Echelon Interception System & the Fundamental Right to Privacy in Europe Kevin J. Lawner Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/pilr Recommended Citation Kevin J. Lawner, Post-Sept. 11th International Surveillance Activity - A Failure of Intelligence: The Echelon Interception System & the Fundamental Right to Privacy in Europe, 14 Pace Int'l L. Rev. 435 (2002) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/pilr/vol14/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace International Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POST-SEPT. 11TH INTERNATIONAL SURVEILLANCE ACTIVITY - A FAILURE OF INTELLIGENCE: THE ECHELON INTERCEPTION SYSTEM & THE FUNDAMENTAL RIGHT TO PRIVACY IN EUROPE Kevin J. Lawner* I. Introduction ....................................... 436 II. Communications Intelligence & the United Kingdom - United States Security Agreement ..... 443 A. September 11th - A Failure of Intelligence .... 446 B. The Three Warning Flags ..................... 449 III. The Echelon Interception System .................. 452 A. The Menwith Hill and Bad Aibling Interception Stations .......................... 452 B. Echelon: The Abuse of Power .................. 454 IV. Anti-Terror Measures in the Wake of September 11th ............................................... 456 V. Surveillance Activity and the Fundamental Right to Privacy in Europe .............................. 460 A. The United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union... 464 B. -

YAF's Comedy and Tragedy 2018-2019

INTRODUCTION 3 METHODOLOGY 4 BIG 10 CONFERENCE 5 University of Illinois 5 Indiana University 5 University of Iowa 6 University of Maryland 7 University of Michigan 7 Michigan State University 8 University of Minnesota 8 University of Nebraska 10 Northwestern University 10 Ohio State University 10 Penn State University 11 Purdue University 12 Rutgers University 12 University of Wisconsin 13 TOP LIBERAL ARTS COLLEGES 14 Williams College 14 Amherst College 17 Swarthmore College 18 Wellesley College 19 Bowdoin College 21 Carleton College 22 Middlebury College 23 Pomona College 24 Claremont McKenna College 25 Davidson College 26 SOUTHEASTERN CONFERENCE 28 University of Alabama 28 University of Arkansas 28 Auburn University 29 Page #1 of #51 University of Florida 29" University of Georgia 29" University of Kentucky 30" Louisiana State University 30" University of Mississippi 31" Mississippi State University 31" University of Missouri 31" University of South Carolina 32" University of Tennessee 32" Texas A&M University 33" Vanderbilt University 33" BIG EAST CONFERENCE 34" Butler University 34" Creighton University 34" DePaul University 35" Georgetown University 37" Marquette University 37" Providence College 38" St. John’s University 38" Seton Hall University 39" Villanova University 39" Xavier University 40" IVY LEAGUE 41" Brown University 41" Columbia University 41" Cornell University 43" Dartmouth College 44" Harvard University 46" University of Pennsylvania 48" Princeton University 50" Yale University 51 Page #2 of #51 INTRODUCTION Young America’s Foundation regularly reviews and audits course catalogs, textbook requirements, commencement speakers, and other key metrics that show the true state of higher education in America. These reports peel back the shiny veneer colleges and universities place on themselves in the name of “higher” education to reveal a stark reality: campuses devoid of intellectual diversity populated with leftist professors, faculty, and administrators intent on indoctrinating the rising generation in the ways of the Left. -

Sexual and Gender Minority Health Research Listening Session Virtual Meeting November 19, 2020, 1:00 P.M.–2:30 P.M

Sexual and Gender Minority Health Research Listening Session Virtual Meeting November 19, 2020, 1:00 p.m.–2:30 p.m. EST [MEETING START TIME: 1:00 P.M. EST] DR. KAREN PARKER: Welcome to the second annual NIH SGM Health Research Listening Session. I’m so happy to be here. My name is Karen Parker, and my pronouns are she and her. I currently serve as director of the Sexual & Gender Minority Research Office at NIH. The primary goal of today’s listening session is for NIH leaders and staff to hear from community stakeholders about what issues are on their mind regarding SGM-related research and related activities at the National Institutes of Health. Selection of these organizations invited today is based on the diversity of organizational missions and efforts. This year, we will have 11 organizations presenting to us. Before we began listening to comments from these stakeholders, we will hear remarks from several senior NIH leaders. We also have several colleagues in attendance from across the different Institutes, Centers, and Offices at the agency, and we are all excited to hear from them. I will be serving as moderator for today’s session, and we will be prompting speakers, both NIH leaders and invited organizational representatives, to turn your audio and video on when it is your time to provide remarks. Please be sure to mute your audio and video feed when you are not speaking. To members of the public who are joining in today to listen, welcome. This session is being recorded, and both a captioned video and transcription document will be posted to the SGMRO website in the coming weeks. -

First Amended Complaint Alleges As Follows

Case 1:20-cv-10541-CM Document 48 Filed 03/05/21 Page 1 of 30 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK In Re: New York City Policing During Summer 2020 Demonstrations No. 20-CV-8924 (CM) (GWG) WOOD FIRST AMENDED This filing is related to: CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT AND Charles Henry Wood, on behalf of himself JURY DEMAND and all others similarly situated, v. City of New York et al., No. 20-CV-10541 Plaintiff Charles Henry Wood, on behalf of himself and all others similarly situated, for his First Amended Complaint alleges as follows: PRELIMINARY STATEMENT 1.! When peaceful protesters took to the streets of New York City after the murder of George Floyd in the summer of 2020, the NYPD sought to suppress the protests with an organized campaign of police brutality. 2.! A peaceful protest in Mott Haven on June 4, 2020 stands as one of the most egregious examples of the NYPD’s excessive response. 3.! It also illustrates the direct responsibility that the leaders of the City and the NYPD bear for the NYPD’s conduct. 4.! Before curfew went into effect for the evening, police in riot gear surrounded peaceful protesters and did not give them an opportunity to disperse. 5.! The police then charged the protesters without warning; attacked them indiscriminately with shoves, blows, and baton strikes; handcuffed them with extremely tight plastic zip ties; and detained them overnight in crowded and unsanitary conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. 1 Case 1:20-cv-10541-CM Document 48 Filed 03/05/21 Page 2 of 30 6.! The NYPD’s highest-ranking uniformed officer, Chief of Department Terence Monahan, was present at the protest and personally oversaw and directed the NYPD’s response. -

Black Lives Matter Syllabus

Black Lives Matter: Race, Resistance, and Populist Protest New York University Fall 2015 Thursdays 6:20-9pm Professor Frank Leon Roberts Fall 2015 Office Hours: (By Appointment Only) 429 1 Wash Place Thursdays 1:00-3:00pm, 9:00pm-10:00pm From the killings of teenagers Michael Brown and Vonderrick Myers in Ferguson, Missouri; to the suspicious death of activist Sandra Bland in Waller Texas; to the choke-hold death of Eric Garner in New York, to the killing of 17 year old Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida and 7 year old Aiyana Stanley-Jones in Detroit, Michigan--. #blacklivesmatter has emerged in recent years as a movement committed to resisting, unveiling, and undoing histories of state sanctioned violence against black and brown bodies. This interdisciplinary seminar links the #blacklivesmatter” movement to four broader phenomena: 1) the rise of the U.S. prison industrial complex and its relationship to the increasing militarization of inner city communities 2) the role of the media industry (including social media) in influencing national conversations about race and racism and 3) the state of racial justice activism in the context of a purportedly “post-racial” Obama Presidency and 4) the increasingly populist nature of decentralized protest movements in the contemporary United States (including the tea party movement, the occupy wall street movement, etc.) Among the topics of discussion that we will debate and engage this semester will include: the distinction between #blacklivesmatter (as both a network and decentralized movement) vs. a broader twenty first century movement for black lives; the moral ethics of “looting” and riotous forms of protest; violent vs.