1602505国連大学conference Report.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“East Asia Low Carbon Growth Dialogue”

UN CLIMATE CHANGE CONFERENCE “East Asia Low Carbon Growth Dialogue” Ministry of Foreign Affairs Japan (MOFA), Ministry of the Environment Japan (MOEJ), Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES), National Institute for Environmental Studies (NIES) & University of Technology Malaysia (UTM) DATE 7 DECEMBER 2015 (MON) TIME 18:30PM – 20:00PM VENUE Observer Room 04 The East Asia Summit (EAS) region is described as the global growth center and the area where emits GHG the most. Stakeholders will discuss concrete steps to realize low carbon development through promotion of public private partnership and introduction of environmental technologies. Time Agenda 18: 30 – 18:40 Opening Remarks H. E. Tamayo Marukawa, Minister of the Environment, Japan Welcome Remarks Prof. Hironori Hamanaka, Chair of the Board of Directors, IGES 18:40 – 18:45 Key note presentation “Achievement of East Asia Low Carbon Growth Partnership” Ambassador Masahiko Horie, MOFA 18:45 – 19:55 Sharing Best Practices - NAMA/MRV framework in Vietnam Dr. Luong Quang Huy, Director, DMHCC/MONRE Vietnam - Joint Crediting Mechanism (JCM) in Cambodia Mr. Sum Thy, Director, MoE Cambodia - Implementation of the Joint Crediting Mechanism (JCM) in Asia Mr. Kazuhisa Koakutsu, Area Leader, IGES - Putrajaya Building Sector Carbon Emissions Monitoring & Reporting Program& PGC2025 updates Datuk Haji Hasim Bin Haji Ismail, President of Putrajaya Corporation, Malaysia Way Forward (1) National planning and city actions (2) Role of non-governmental organizations Panelist: Ambassador Masahiko Horie (MOFA), Mr. Kentaro Tamura (IGES), Prof. Ho Chin Siong (UTM), Dr. Dr. Luong Quang Huy (Vietnam), Mr. Sum Thy (Cambodia) 19:55 – 20:00 Closing Remarks Datuk Ismail Ibrahim, Chief Executive, Iskandar Regional Development Authority (IRDA) Moderator: Dr. -

On the Descrippon About Childhood Thyroid Cancer in UNSCEAR White

1 Workshop on the occasion of Dr. Mar-n Tondel vising Osaka /20 On the descrip-on about childhood thyroid cancer in UNSCEAR White Paper 2016 Tomoya Yamauchi Graduate School of Mari-me Sciences, Kobe Univreisty 21st April 2019 Shin-Osaka Maru-biru Bekkan, 5-3 On the descrip-on of childhood thyroid Cancer in UNSCEAR White Paper 2016 2/20 Focusing on two paragraphs of 111 & 112 in UNSEAR 2016 White Paper, we examine by what way they deny the analy-cal result of the excess of childhood thyroid cancer in Fukushima Prefecture based on the conven-onal epidemiology. As the report style, these paragraph is completely out of usual scien-fic manner. They have never adequate knowledge about epidemiology, especially on the role of regional classificaon as an operaon variable, an importance of external comparison based on ordinal incidence, and -me interval aer the exposure. The main paper in the present discussion is that published by Tsuda et al. in Epidemiology in 2016. ORIGINAL ARTICLE 5IZSPJE$BODFS%FUFDUJPOCZ6MUSBTPVOE"NPOH 3FTJEFOUT"HFT:FBSTBOE:PVOHFSJO'VLVTIJNB +BQBOUP Toshihide Tsuda,a Akiko Tokinobu,b Eiji Yamamoto,c and Etsuji Suzukib the assumption that the rest of examinees were disease free, an incidence Background: After the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami ORIGINAL ARTICLE rate ratio of 12 has already been observed (95% CI = 5.1, 23). in March 2011, radioactive elements were released from the Fuku- Conclusions: An excess of thyroid cancer has been detected by shima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. Based on prior knowledge, con- ultrasound among children and adolescents in Fukushima Prefecture cern emerged about whether an increased incidence of thyroid cancer within 4 years of the release, and is unlikely to be explained by a among exposed residents would occur as a result. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents President’s Message .......................................................................................................................................5 40 Years of JCIE .................................................................................................................................................8 JCIE Activities: April 2009–March 2011 ..................................................................................................... 12 Global ThinkNet: Policy Research and Dialogue 15 Policy Studies and Dialogue .................................................................................................................... 16 Asia Pacific Agenda Project Growing Asia Pacific Regionalism and New Opportunities to Advance Nontraditional Security Cooperation The Impact of Changing US Policy on the Emerging East Asia Community 15th APAP Forum, Seoul Dialogue and Research Monitor Statistical Database on East Asia Regional Community Building East Asia Insights: Toward Community Building Reinvigorating US-Japan Policy Dialogue and Discussion in a Time of Political Change Managing China-Japan-US Relations and Strengthening Trilateral Cooperation Strengthening Nongovernmental Contributions to Regional Security Cooperation An Enhanced Agenda for US-Japan Partnership Seminars and Roundtables ...........................................................................................................................24 Roundtable on the Role of China in East Asia Community Building Joint Seminar on North Korea -

In Japan 2016 on the Environment

Annual Report on the Environment in Japan 2016 Annual Report on the Environment 02 in Japan 2016 03 Table of Contents Foreword Foreword - 03 A new stage for global e year 2015 was a historic one for the global environment. In October, the United Nations General Assembly adopted warming countermeasures - 04 1 the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, a universal (1) A new international framework to address global warming - 05 (2) Japan’s global warming countermeasures - 06 set of goals and targets for achieving sustainable development (3) Plan for adaptation to climate change - 08 that involve the entire world. In December, the 21st Confer- (4) Research and development - 10 ence of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Con- (5) Green finance - 12 vention on Climate Change (COP21) adopted the Paris (6) International cooperation - 12 (7) Strategic actions targeting the long-term goal - 13 Agreement, the rst legally binding agreement since the Tamayo Marukawa (8) Other international frameworks - 14 Kyoto Protocol eighteen years earlier. And, in May 2016 in Minister of the Environment Japan, the Cabinet approved the Plan for Global Warming Reconstruction after Countermeasures, the G7 Ise-Shima Summit was held in Ise-Shima, Mie Prefecture, and the G7 Toyama Environment the Great East Japan Earthquake - 16 2 Ministers’ Meeting was held in Toyama City, Toyama Prefec- (1) Progress in restoration of the environment - 17 ture. Both internationally and domestically, it could be said (2) Restoration of the environment in areas contaminated - 18 by radioactive materials that global warming countermeasures and the creation of a (3) Health management for people exposed to radiation - 20 sustainable society have entered a new stage. -

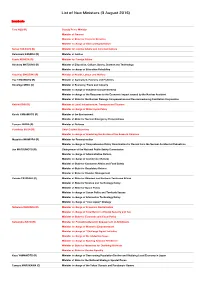

List of New Ministers (3 August 2016)

List of New Ministers (3 August 2016) Incumbents Taro ASO (R) Deputy Prime Minister Minister of Finance Minister of State for Financial Services Minister in charge of Overcoming Deflation Sanae TAKAICHI (R) Minister for Internal Affairs and Communications Katsutoshi KANEDA (R) Minister of Justice Fumio KISHIDA (R) Minister for Foreign Affairs Hirokazu MATSUNO (R) Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Minister in charge of Education Rebuilding Yasuhisa SHIOZAKI (R) Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare Yuji YAMAMOTO (R) Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Hiroshige SEKO (C) Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry Minister in charge of Industrial Competitiveness Minister in charge of the Response to the Economic Impact caused by the Nuclear Accident Minister of State for the Nuclear Damage Compensation and Decommissioning Facilitation Corporation Keiichi ISHII (R) Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Minister in charge of Water Cycle Policy Koichi YAMAMOTO (R) Minister of the Environment Minister of State for Nuclear Emergency Preparedness Tomomi INADA (R) Minister of Defense Yoshihide SUGA (R) Chief Cabinet Secretary Minister in charge of Alleviating the Burden of the Bases in Okinawa Masahiro IMAMURA (R) Minister for Reconstruction Minister in charge of Comprehensive Policy Coordination for Revival from the Nuclear Accident at Fukushima Jun MATSUMOTO (R) Chairperson of the National Public Safety Commission Minister in charge of Administrative Reform Minister in charge of Civil Service -

2016 Country Review

Japan 2016 Country Review http://www.countrywatch.com Table of Contents Chapter 1 1 Country Overview 1 Country Overview 2 Key Data 4 Japan 5 Asia 6 Chapter 2 8 Political Overview 8 History 9 Political Conditions 11 Political Risk Index 66 Political Stability 81 Freedom Rankings 96 Human Rights 108 Government Functions 110 Government Structure 112 Principal Government Officials 117 Leader Biography 120 Leader Biography 120 Foreign Relations 122 National Security 152 Defense Forces 154 Chapter 3 157 Economic Overview 157 Economic Overview 158 Nominal GDP and Components 162 Population and GDP Per Capita 164 Real GDP and Inflation 165 Government Spending and Taxation 166 Money Supply, Interest Rates and Unemployment 168 Foreign Trade and the Exchange Rate 169 Data in US Dollars 170 Energy Consumption and Production Standard Units 171 Energy Consumption and Production QUADS 173 World Energy Price Summary 174 CO2 Emissions 175 Agriculture Consumption and Production 176 World Agriculture Pricing Summary 179 Metals Consumption and Production 180 World Metals Pricing Summary 183 Economic Performance Index 184 Chapter 4 196 Investment Overview 196 Foreign Investment Climate 197 Foreign Investment Index 202 Corruption Perceptions Index 215 Competitiveness Ranking 226 Taxation 235 Stock Market 236 Partner Links 237 Chapter 5 238 Social Overview 238 People 239 Human Development Index 242 Life Satisfaction Index 245 Happy Planet Index 257 Status of Women 266 Global Gender Gap Index 268 Culture and Arts 278 Etiquette 278 Travel Information 281 Diseases/Health Data 291 Chapter 6 297 Environmental Overview 297 Environmental Issues 298 Environmental Policy 299 Greenhouse Gas Ranking 300 Global Environmental Snapshot 311 Global Environmental Concepts 323 International Environmental Agreements and Associations 337 Appendices 361 Bibliography 362 Japan Chapter 1 Country Overview Japan Review 2016 Page 1 of 374 pages Japan Country Overview JAPAN Japan's first contact with the Western world came in 1542 when a Portuguese ship landed on its shore. -

1 a Historical Constructivist Perspective of Japan's

A Historical Constructivist Perspective of Japan’s Environmental Diplomacy Katsuhiko Mori International Christian University Abstract: Why did Japan attempt to take a leadership role on some occasions, while it became a bystander or even a dragger on other occasions? By examining three cases of environmental diplomacy, i.e., hosting the Kyoto conference on climate change, the Nagoya conference on biodiversity, and the diplomatic conference for the Minamata Convention, this paper will identify the key drivers of effectiveness in Japan’s environmental diplomacy from the perspective of historical constructivism. The study accounts for the historical trajectory and conjunctures of Japan’s environmental diplomacy in the changing global environmental governance with a combination of power, interests, and ideas across time and areas of concern at both international and domestic levels. Introduction Why did Japan attempt to take a leadership role on some occasions, while it became a bystander or even a dragger on other occasions? In the 1980s, Japan was accused of being one of the world’s “eco-outlaws,” especially regarding the tropical timber, whaling, and ivory trades.1 Since the 1990s, Japan has become more active in hosting multilateral environmental conferences, such as the 1997 Third Session of the Conference of Parties (COP-3) of the United Nations (UN) Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the 2010 COP-10, the fifth Meeting of the Parties to the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety (MOP-5) of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), and the 2013 Diplomatic Conference for the Minamata Convention on Mercury. These conferences were concerned with the atmosphere, biosphere, and hydrosphere, which were on the diplomatic agenda in the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s, respectively. -

Cross-Sectoral Cooperation on Global ISSUES

CROSS-SECTORAL COOperatiON ON GLOBAL ISSUES As the challenges facing Japan and the international community have become more complex, it has become apparent that there is a need for greater coordination and cooperation among diverse sectors of society, both domestically and internationally. A growing number of JCIE’s initiatives now cut across its three programmatic pillars—policy studies, political exchange, and civil so- ciety programs—drawing on the expertise and strong networks developed in these areas and bringing together leaders from various fields in order to effectively respond to emerging issues that cannot be dealt with solely by one sector of society. For example, JCIE’s program on global health and hu- man security, which attempts to deal in a comprehensive manner with the interconnected health threats facing individuals and communities in developing countries, would not be effective without the active involvement of policy experts and scholars, politicians, and civil society organizations. As part of this program, JCIE also serves as secretariat of the Friends of the Global Fund, Japan, which builds support in Japan and throughout Asia for the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. Finally, JCIE undertakes special initiatives to encourage the development of the next generation of international leaders across sectors. Friends of the Global Fund, Japan In 2004, JCIE founded the Friends of the Global Fund, important to mobilize leadership in other sectors of Japan (FGFJ), a private support group for the Global society as well, ranging from business to civil soci- Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. The ety, academia, and medicine. -

A New Stage for Global Warming Countermeasures Plan for Global Warming in Japan 2016 07 2 Countermeasures the Plan for Global Warming Countermeasures

Annual Report on the Environment 04 in Japan 2016 05 1 A new international framework to address global warming e Paris Agreement e Paris Agreement was adopted at the 21st At the opening ceremony of the COP21 leaders’ Conference of the Parties to the United Nations segment, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe reasserted A new stage for Framework Convention on Climate Change this policy, indicated that the new international (COP21) held in Paris, France from November 30 framework should include the setting of a long-term to December 13, 2015. It is the rst legally binding goal as well as the establishment of a common international agreement since the Kyoto Protocol process for the review of NDCs (Photo below) and eighteen years earlier. also announced “Actions for Cool Earth 2.0 (ACE 2.0)”. Representing the Japanese government at the global warming e Paris Agreement is considered a groundbreak- high-level segment, Minister of the Environment ing international framework. It is the rst interna- Tamayo Marukawa stated that the legal agreement tional treaty to agree to “holding the increase in should include a global long term goal, a cycle the global average temperature to well below 2°C whereby all Parties communicate and update their above pre-industrial levels.” It includes “pursuing NDCs, and a report and review system. countermeasures eorts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C Japan strongly welcomes and highly appreciates the above pre-industrial levels” and sets a goal “to adoption of the Paris Agreement, which is a fair achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions and eective international framework applicable to by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse all parties. -

Collective View Highlighted in Biden Shift

10 | Friday, March 5, 2021 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY WORLD Another Collective view SpaceX rocket in highlighted in fiery end WASHINGTON — Third time’s a charm? Not so for SpaceX, whose Biden shift unmanned rocket exploded on the ground on Wednesday after carry- ing out what had seemed to be a suc- Security guidance positions US for cessful flight and landing — fresh on the heels of two fiery crashes. global cooperation — China included It was yet another flub involving a prototype of the Starship rocket, By ZHAO HUANXIN in Washington Biden also stressed that the US’ Games organizers in Tokyo take part in a meeting with Olympic officials on Wednesday. which SpaceX hopes one day to [email protected] strength abroad derives from DU XIAOYI / XINHUA send to Mars. building back better at home, “A beautiful soft landing,” a SpaceX The White House on Wednesday which should start by “decisively commentator said on a live broad- vowed to build back better at home responding to the public health cast of the test flight, although flames and reembrace international coop- and economic crises unleashed by Foreign fans likely to miss out on Games were coming out at the bottom and eration while stressing that “strate- COVID-19”. crews were trying to put them out. gic competition” with China should The document singled out China The rocket exploded a few min- not preclude collaboration. That and Russia as main threats and By WANG XU in Tokyo Japan’s Minister for the Tokyo respect, we may have to set one or utes later, lurching into the air and message was set out in the interim vowed to build up “enduring advan- [email protected] Olympic and Paralympic Games, another priority.” crashing back to the ground.