The Alpha Kappa Phi Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

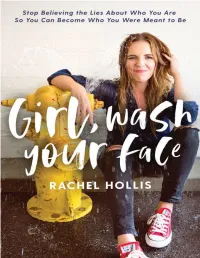

Girl, Wash Your Face

PRAISE FOR Girl, Wash Your Face “If Rachel Hollis tells you to wash your face, turn on that water! She is the mentor every woman needs, from new mommas to seasoned business women.” —ANNA TODD, New York Times and #1 internationally bestselling author of the After series “Rachel’s voice is the winning combination of an inspiring life coach and your very best (and funniest) friend. Shockingly honest and hilariously down to earth, Girl, Wash Your Face is a gift to women who want to flourish and live a courageously authentic life.” —MEGAN TAMTE, founder and co-CEO of Evereve “There aren’t enough women in leadership telling other women to GO FOR IT. We typically get the caregiver; we rarely get the boot camp instructor. Rachel lovingly but firmly tells us it is time to stop letting the tail wag the dog and get on with living our wild and precious lives. Girl, Wash Your Face is a dose of high-octane straight talk that will spit you out on the other end chasing down dreams you hung up long ago. Love this girl.” —JEN HATMAKER, New York Times bestselling author of For the Love and Of Mess and Moxie and happy online hostess to millions every week “In Rachel Hollis’s first nonfiction book, you will find she is less cheerleader and more life coach. This means readers won’t just walk away inspired, they will walk away with the right tools in hand to actually do their dreams. Dream doing is what Rachel is all about it. -

The Fifth Sunday in Lent March 13, 2016

The Fifth Sunday in Lent March 13, 2016 Holy Cross Evangelical Lutheran Church Lutheran Church Canada 322 East Avenue, Kitchener, Ontario N2H 1Z5 (519)742-5812 www.holycrosskitchener.org “By God’s grace, the members of Holy Cross Evangelical Lutheran Church will be a caring, vibrant diverse community of blessed believers, lovingly reaching out with the message of Jesus Christ.” – Vision Statement 2010 Volume 69 No. 11 March 13, 2016 The Fifth Sunday in Lent 8:30 & 11:00 am – Divine Services 9:45 am – Sunday School, and Bible Classes for All Ages 3:30 pm – Slovak Congregation Service 6:30 pm – Adult Instruction Class Entrance Hymn Drawn to the Cross LSB #560 Invocation & Psalm 126 Pastor In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. People Amen. Pastor The LORD has done great things for us; we are glad. When the LORD restored the fortunes of Zion, we were like those who dream. People The LORD has done great things for us; we are glad. Pastor Then our mouth was filled with laughter, and our tongue with shouts of joy; People the LORD has done great things for us; we are glad. Pastor Then they said among the nations, “The LORD has done great things for them.” People The LORD has done great things for us; we are glad. Pastor Restore our fortunes, O LORD, like streams in the Negeb! Those who sow in tears shall reap with shouts of joy! People The LORD has done great things for us; we are glad. -

Le Harcèlement Sexuel : Clarification

Université de Montréal L’évolution des représentations des crimes sexuels et du harcèlement sexuel dans les téléséries américaines de fiction post #Metoo. Par Françoise Goulet-Pelletier Département d’histoire de l’art et d’études cinématographiques Faculté des arts et des sciences Mémoire présenté à la Faculté des études supérieures et postdoctorales en vue de l’obtention du grade de M.A. en études cinématographiques, option recherche. Décembre 2019 © Françoise Goulet-Pelletier, 2019 ii Université de Montréal Unité académique : Département d’histoire de l’art et d’études cinématographiques Ce mémoire intitulé L’évolution des représentations des crimes sexuels et du harcèlement sexuel dans les téléséries américaines post #Metoo. Présenté par Françoise Goulet-Pelletier A été évalué par un jury composé des personnes suivantes Isabelle Raynauld Directrice de recherche Marta Boni Membre du jury Stéfany Boisvert Membre du jury iii Résumé Le mouvement social #Metoo a bouleversé les mœurs et les façons de penser quant aux enjeux liés au harcèlement sexuel et aux abus sexuels. En effet, en automne 2017, une vague de dénonciations déferle sur la place publique et peu à peu, les frontières de ce qui est acceptable ou pas semblent se redéfinir au sein de plusieurs sociétés. En partant de cette constatation sociétale, nous avons cru remarquer une reprise des enjeux entourant le mouvement social #Metoo dans les séries télévisées américaines de fiction. Ce mémoire souhaite illustrer et analyser l’évolution des représentations des crimes sexuels et du harcèlement sexuel inspirée par le mouvement #Metoo. En reprenant les grandes lignes de ce mouvement, cette étude s’attarde sur son impact sur la société nord-américaine. -

The Cold Equations by Tom Godwin

The Cold Equations by Tom Godwin He was not alone. There was nothing to indicate the fact but the white hand of the tiny gauge on the board before him. The control room was empty but for himself; there was no sound other than the murmur of the drives—but the white hand had moved. It had been on zero when the little ship was launched from the Stardust; now, an hour later, it had crept up. There was something in the supplies closet across the room, it was saying, some kind of a body that radiated heat. It could be but one kind of a body—a living, human body. He leaned back in the pilot's chair and drew a deep, slow breath, considering what he would have to do. He was an EDS pilot, inured to the sight of death, long since accustomed to it and to viewing the dying of another man with an Commented [JB1]: Def: to make tough or harden by exposure objective lack of emotion, and he had no choice in what he must do. There could be no alternative—but it required a few moments of conditioning for even an EDS pilot to prepare himself to walk across the room and coldly, deliberately, take the life of a man he had yet to meet. He would, of course, do it. It was the law, stated very bluntly and definitely in grim Paragraph L, Section 8, of Interstellar Regulations: Any stowaway discovered in an EDS shall be jettisoned immediately following discovery. Commented [JB2]: Def: to throw overboard to lighten a vessel or aircraft It was the law, and there could be no appeal. -

Gender and Bodies in the Netflix Series "YOU" Morgan Bates Longwood University

Longwood University Digital Commons @ Longwood University Spring Showcase for Research and Creative Inquiry Research & Publications Spring 2019 From Desire to Obsession: Gender and Bodies in the Netflix Series "YOU" Morgan Bates Longwood University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.longwood.edu/rci_spring Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bates, Morgan, "From Desire to Obsession: Gender and Bodies in the Netflix Series "YOU"" (2019). Spring Showcase for Research and Creative Inquiry. 10. https://digitalcommons.longwood.edu/rci_spring/10 This Poster is brought to you for free and open access by the Research & Publications at Digital Commons @ Longwood University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Spring Showcase for Research and Creative Inquiry by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Longwood University. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. From Desire to Obsession: Gender & Bodies in the Netflix Series “YOU” Morgan Bates Longwood University Thesis Abstract The show YOU exhibits how stalking is gendered and how it The intention of this poster presentation is to display a Supporting Point 3: further exemplifies the ceaseless male necessity to control personal interpretation of the show as well as the themes, • Connection to Gender and Bodies: women particularly once romantically involved. The series issues, and a connection to gender and bodies allows for the audience to see how easy stalking can be in our throughout the series. The show exemplifies how stalking is a gendered obsession modern age and how it generally involves toxic masculinity for male control over women. Joe believes, as a male, his intertwined with femininity. -

Along the Ohio Trail

Along The Ohio Trail A Short History of Ohio Lands Dear Ohioan, Meet Simon, your trail guide through Ohio’s history! As the 17th state in the Union, Ohio has a unique history that I hope you will find interesting and worth exploring. As you read Along the Ohio Trail, you will learn about Ohio’s geography, what the first Ohioan’s were like, how Ohio was discovered, and other fun facts that made Ohio the place you call home. Enjoy the adventure in learning more about our great state! Sincerely, Keith Faber Ohio Auditor of State Along the Ohio Trail Table of Contents page Ohio Geography . .1 Prehistoric Ohio . .8 Native Americans, Explorers, and Traders . .17 Ohio Land Claims 1770-1785 . .27 The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 . .37 Settling the Ohio Lands 1787-1800 . .42 Ohio Statehood 1800-1812 . .61 Ohio and the Nation 1800-1900 . .73 Ohio’s Lands Today . .81 The Origin of Ohio’s County Names . .82 Bibliography . .85 Glossary . .86 Additional Reading . .88 Did you know that Ohio is Hi! I’m Simon and almost the same distance I’ll be your trail across as it is up and down guide as we learn (about 200 miles)? Our about the land we call Ohio. state is shaped in an unusual way. Some people think it looks like a flag waving in the wind. Others say it looks like a heart. The shape is mostly caused by the Ohio River on the east and south and Lake Erie in the north. It is the 35th largest state in the U.S. -

The Tufts Daily

CLUB SPORTS Analyzing the accuracy of a certain “National Treasure” With newfound club status, see ARTS&LIVING / PAGE 4 Club Cricket looks to continue Editorial: Inequitable health accommodations harm SEE SPORTS / BACK PAGE student outcomes see OPINION / PAGE 7 THE INDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWSPAPER OF TUFTS UNIVERSITY EST. 1980 HE UFTS AILY VOLUME LXXIX, ISSUE 14T T D MEDFORD/SOMERVILLE, MASS. THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 13, 2020 tuftsdaily.com TCA rallies, petitions for Students mobilize in New divestment from fossil fuel Hampshire for Sanders, industry Buttigieg, Warren Disclaimer: Hannah Kahn is a former New Hampshire was the first prima- executive audio producer at the Daily. ry election, which followed the Iowa cau- Hannah was not involved in the writing or cuses last week that similarly ended with editing of this article. Buttigieg and Sanders on top. In Iowa, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders won Buttigieg received 26.2% of the votes and the New Hampshire primary election on Sanders got 26.1%. Tuesday with 25.7% of the vote, followed In Iowa, however, Warren followed more closely by former Mayor Pete Buttigieg of closely behind Sanders and Buttigieg with South Bend, Ind. with 24.4% of the vote. 18% of the vote. Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar out- “In New Hampshire and in Iowa, it’s not performed expectations, coming in third what we were hoping for, but it is what it at 19.8%, while Massachusetts Senator is,” co-president of Tufts for Warren and Elizabeth Warren and former Vice President first-year Amanda Westlake said. Joe Biden faltered, winning 9.2% and 8.4% Westlake leads Tufts for Warren along of the vote, respectively. -

Children of the Heav'nly King: Religious Expression in the Central

Seldom has the folklore of a particular re- CHILDREN lar weeknight gospel singings, which may fea gion been as exhaustively documented as that ture both local and regional small singing of the central Blue Ridge Mountains. Ex- OF THE groups, tent revival meetings, which travel tending from southwestern Virginia into north- from town to town on a weekly basis, religious western North Carolina, the area has for radio programs, which may consist of years been a fertile hunting ground for the HE A"' T'NLV preaching, singing, a combination of both, most popular and classic forms of American .ft.V , .1 the broadcast of a local service, or the folklore: the Child ballad, the Jack tale, the native KING broadcast of a pre-recorded syndicated program. They American murder ballad, the witch include the way in which a church tale, and the fiddle or banjo tune. INTRODUCTORY is built, the way in which its interi- Films and television programs have or is laid out, and the very location portrayed the region in dozens of of the church in regard to cross- stereotyped treatments of mountain folk, from ESS A ....y roads, hills, and cemetery. And finally, they include "Walton's mountain" in the north to Andy Griffith's .ft. the individual church member talking about his "Mayberry" in the south. FoIklor own church's history, interpreting ists and other enthusiasts have church theology, recounting char been collecting in the region for acter anecdotes about well-known over fifty years and have amassed preachers, exempla designed to miles of audio tape and film foot illustrate good stewardship or even age. -

Lansburgh & Bro

Bra and Jenale De Cammw an@ Xt= Anabl ment of the north end Boundary on the TIM Wei~mor 8OL Luas of Wellsburg, W. V. Dyrenforth tract of land. H. ZIRKIN, A iesolnvam was altered requesting that Mrs. Lydia A. Crutchield and Mrs. Umm. the Commsmmoners recommend to Congress Importer and Mfr. of High-Grade Furs EIBROP 5*A!N3nE C. Reed f LouisvIlle. Ky.: Mrs. Rosa P: that all of lot A. in the subdivision of lJni- & Bro. Fourteenth St. O1gIOZA5P1E Cooke of Worthington, Ind.; Mrs. M. A. versity Park. and all of lot 14, In block 18; Lansburgh 825 Hanenman of New Alnny, Ind.. and Mrs. and lot 14 In block 18. in Meridian Hill. be AT THE EPIPEANT TODAY. A. F. Triggs of Wilmington. Del., are visit- condemned, and that lot 20 and lot 11. block Ing their brother. N. R. Young at TV7 8th 12, Meridian Mill' be also condemned and street northeasm dedicated an a public reservation. Silk Values of Beautiful of Mr. A. Fry offered a resolution to the ef- Importance. Wedding im. Ingraham Robert Farnham Swayse, formerly of this fect that a bill be prepared to open 17eth and Kr. J'ewett-Other EJtri- city, but for the past eleven years In New street from Fiorida avenue to the Wal- A announcement. Satisfaction is the York. was married Wednesday, October 9, bridge subdivision or Park street. It was highly important key- In His bride was Miss Adelaide can be said about these moanal Events-Notee, Brookly. adepted. note to every yard offered. The best that Noyes-of Brooklyn. -

Representation of Psychopathic Characteristics in Fiction

Representation of Psychopathic Characteristics in Fiction A Transitivity Analysis of the Protagonist’s External and Internal Dialogue in the TV-series You Author: Madeleine Olsson Supervisor: Jukka Tyrkkö Examiner: Charlotte Hommerberg Term: Autumn 20 Subject: Linguistics Level: Bachelor Course code: 2EN10E Abstract The series You (2018) challenges the traditional characteristics of a protagonist and introduces the audience to a psychopathic protagonist with traits which are typically recognised in the traditional villain. This study investigates the portrayal of the fictional character Joe Goldberg’s psychopathic characteristics by analysing the language used in his external and internal dialogues. More specifically, drawing on the tools of transitivity analysis (Halliday 1985), the study focuses on the process types and corresponding semantic roles assigned to the pronouns I and you used by the protagonist over the course of three strategically selected episodes of the series. The results of the qualitative and quantitative transitivity analysis of internal and external dialogues throughout three chosen episodes shows that in the internal dialogues Joe appears analytical and assigns attributes and actions to you which correspond to the mental representation of the object of his desire, Beck. While Joe’s internal dialogues ascribe some appealing attributes to Beck, the transitivity analysis also shows that he identifies traits of vulnerability, such as lack of confidence and being indolent in reaching her goals. In contrast, Joe’s approach in the external dialogues continuously appears to project him as a humble person who puts the needs of others before his own, expressing deep consideration and understanding of the needs and emotions of others. -

August 2021 Newsletter

2021 A Note from the Pastor ….……. Let's Talk Apps and Aptitudes Recently, I attended a technology class for senior adults. I was surprised by the number of seniors present. I was also sur- prised no one thought me too young to be there with them. The instructors that day were in their 30s, 40s, and teens. The class worked with laptops and cell phones. The instructions centered around how to use Google apps and the benefits they offered. Most apps were presented as a tool to make life simpler and keep us connected with family. The class covered things like downloading photos, creating albums for saved images making them easily retrievable and creating shared files that allowed you to organize events with family assisting in providing input electronically. There was even a lesson on using the calendar app where each family member could include their schedule. The instructor color- coded her calendar. We could see she had a different color for each child and color for her personal schedule. I was some- what skeptical of that working for me. The likelihood of my children sharing details of their daily activities was laughable. I don't know if the instructor saw my raised eyebrow. She soon confessed that one of her adult sons was not always faithful to document his whereabouts. That got a big laugh and nods from the class. The class was informative. I really admired how the young assistants were patient with their elders. There was no name- calling. No laughing because of confusion. It was nice to see youth and elders working side by side. -

Make It New: Reshaping Jazz in the 21St Century

Make It New RESHAPING JAZZ IN THE 21ST CENTURY Bill Beuttler Copyright © 2019 by Bill Beuttler Lever Press (leverpress.org) is a publisher of pathbreaking scholarship. Supported by a consortium of liberal arts institutions focused on, and renowned for, excellence in both research and teaching, our press is grounded on three essential commitments: to be a digitally native press, to be a peer- reviewed, open access press that charges no fees to either authors or their institutions, and to be a press aligned with the ethos and mission of liberal arts colleges. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, California, 94042, USA. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11469938 Print ISBN: 978-1-64315-005- 5 Open access ISBN: 978-1-64315-006- 2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944840 Published in the United States of America by Lever Press, in partnership with Amherst College Press and Michigan Publishing Contents Member Institution Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Jason Moran 21 2. Vijay Iyer 53 3. Rudresh Mahanthappa 93 4. The Bad Plus 117 5. Miguel Zenón 155 6. Anat Cohen 181 7. Robert Glasper 203 8. Esperanza Spalding 231 Epilogue 259 Interview Sources 271 Notes 277 Acknowledgments 291 Member Institution Acknowledgments Lever Press is a joint venture. This work was made possible by the generous sup- port of