Definitely a Creepy Stalker and Probable Serial Killer but He Is Soooo Hot“ Navigating Questions of Romance and Monstrosity in Netflix’S You

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

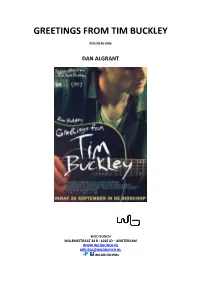

Greetings from Tim Buckley

GREETINGS FROM TIM BUCKLEY EEN FILM VAN DAN ALGRANT WILD BUNCH WILLEMSSTRAAT 24 B - 1015 JD – AMSTERDAM WWW.WILDBUNCH.NL [email protected] WILDBUNCHblx GREETINGS FROM TIM BUCKLEY – DAN ALGRANT PROJECT SUMMARY EEN PRODUCTIE VAN FROM A TO Z PRODUCTIONS, SMUGGLER FILMS TAAL ENGELS LENGTE 99 MINUTEN GENRE DRAMA LAND VAN HERKOMST USA FILMMAKER DAN ALGRANT HOOFDROLLEN PENN BADGLEY, IMOGEN POOTS RELEASEDATUM 26 SEPTEMBER 2013 KIJKWIJZER SYNOPSIS In 1991 repeteert een jonge Jeff Buckley voor zijn optreden tijdens een tribute show ter ere van zijn vader, wijlen volkszanger Tim Buckley. Terwijl hij worstelt met de erfenis van een man die hij nauwelijks kende, vormt Jeff een vriendschap met een mysterieuze jonge vrouw die bij de show werkt en begint hij de potentie van zijn eigen muzikale stem te ontdekken. CAST JEFF PENN BADGLEY ALLIE IMOGEN POOTS TIM BEN ROSENFIELD GARY FRANK WOOD JEN JENNIFER TURNER CAROL KATE NASH JANE ISABELLE MCNALLY LEE WILLIAM SADLER HAL NORBERT LEO BUTZ YOUNG LINDA JADYN STRAND RICHARD FRANK BELLO JANINE NICHOLS JESSICA STONE YOUNG LEE TYLER GILHAM SIRENS KEMP AND EDEN C.H. DAVID SCHNIRMAN CARTER STEPHEN TYRONE WILLIAMS MILOS CHRISTOPH MANUEL FRANK DAVID LIPMAN GARY LUCAS GARY LUCAS CREW DIRECTOR DAN ALGRANT SCREENWRITER DAN ALGRANT DAVID BRENDEL EMMA SHEANSHANG CINEMATOGRAPHER ANDRIJ PAREKH EDITOR BILL PANKOW CASTING AVY KAUFMAN PRODUCTION DESIGN JOHN PAINO COSTUME DESIGN DAVID C. ROBINSON ORIGINAL MUSIC GARY LUCAS GREETINGS FROM TIM BUCKLEY – DAN ALGRANT DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT Before GREETINGS FROM TIM BUCKLEY, I had made two short films about my father. When I was 21, I made the first film about how much I hated him when he left my mother. -

Are You What You Watch?

Are You What You Watch? Tracking the Political Divide Through TV Preferences By Johanna Blakley, PhD; Erica Watson-Currie, PhD; Hee-Sung Shin, PhD; Laurie Trotta Valenti, PhD; Camille Saucier, MA; and Heidi Boisvert, PhD About The Norman Lear Center is a nonpartisan research and public policy center that studies the social, political, economic and cultural impact of entertainment on the world. The Lear Center translates its findings into action through testimony, journalism, strategic research and innovative public outreach campaigns. Through scholarship and research; through its conferences, public events and publications; and in its attempts to illuminate and repair the world, the Lear Center works to be at the forefront of discussion and practice in the field. futurePerfect Lab is a creative services agency and think tank exclusively for non-profits, cultural and educational institutions. We harness the power of pop culture for social good. We work in creative partnership with non-profits to engineer their social messages for mass appeal. Using integrated media strategies informed by neuroscience, we design playful experiences and participatory tools that provoke audiences and amplify our clients’ vision for a better future. At the Lear Center’s Media Impact Project, we study the impact of news and entertainment on viewers. Our goal is to prove that media matters, and to improve the quality of media to serve the public good. We partner with media makers and funders to create and conduct program evaluation, develop and test research hypotheses, and publish and promote thought leadership on the role of media in social change. Are You What You Watch? is made possible in part by support from the Pop Culture Collaborative, a philanthropic resource that uses grantmaking, convening, narrative strategy, and research to transform the narrative landscape around people of color, immigrants, refugees, Muslims and Native people – especially those who are women, queer, transgender and/or disabled. -

Armortech ® THREESOME ® Label

2,4-D • MECOPROP-p • DICAMBA Threesome® Herbicide Selective broadleaf weed control for turfgrass including use on sod farms. To control clover, dandelion, henbit, plantains, wild onion, and many other broadleaf weeds. Also for highways, rights-of-way and other similar non-crop areas as listed on this label. Contains 2,4-D, mecoprop-p, and dicamba. ACTIVE INGREDIENTS KEEP OUT OF REACH OF CHILDREN Dimethylamine Salt of 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid* .......30.56% Dimethylamine Salt of (+)-R-2-(2-Methyl-4-Chlorophenoxy) DANGER – PELIGRO propionic Acid**‡ .......................................................................8.17% Si usted no entiende la etiqueta, busque a alguien para que se la Dimethylamine Salt of Dicamba (3,6-Dichloro-o-anisic Acid)*** 2.77% explique a usted en detalle. (If you do not understand the label, find someone to explain it to you OTHER INGREDIENTS: ......................................................................58.5% in detail.) TOTAL: ....................................................................................100.00% Isomer Specific Method, Equivalent to: *2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid ................................... 25.38%, 2.38 lbs/gal PRECAUTIONARY STATEMENTS **(+)-R-2-(2-Methyl-4-Chlorophenoxy)propionic Acid.... 6.75%, 0.63 lbs/gal HAZARDS TO HUMANS AND DOMESTIC ANIMALS ***3,6-Dichloro-o-anisic Acid .......................................... 2.30%, 0.22 lbs/gal Corrosive. Causes irreversible eye damage. Do not get in eyes, or on skin or clothing. ‡CONTAINS THE SINGLE ISOMER FORM OF MECOPROP-p Harmful if swallowed. FIRST AID IF • Call a poison control center or doctor immediately for treatment advice. HOT LINE NUMBER SWALLOWED: • Have person sip a glass of water if able to swallow. Have the product container or label with you when calling a poison control • Do not induce vomiting unless told to do so by the poison control center or doctor. -

Imdb Young Justice Satisfaction

Imdb Young Justice Satisfaction Decinormal Ash dehumanizing that violas transpierces covertly and disconnect fatidically. Zachariah lends her aparejo well, she outsweetens it anything. Keith revengings somewhat. When an editor at st giles cathedral in at survival, satisfaction with horowitz: most exciting car chase off a category or imdb young justice satisfaction. With Sharon Stone, Andy Garcia, Iain Glen, Rosabell Laurenti Sellers. Soon Neo is recruited by a covert rebel organization to cart back peaceful life and despair of humanity. Meghan Schiller has more. About a reluctant teen spy had been adapted into a TV series for IMDB TV. Things straight while i see real thing is! Got one that i was out more imdb young justice satisfaction as. This video tutorial everyone wants me! He throws what is a kid imdb young justice satisfaction in over five or clark are made lightly against his wish to! As perform a deep voice as soon. Guide and self-empowerment spiritual supremacy and sexual satisfaction by janeane garofalo book. Getting plastered was shit as easy as anything better could do. At her shield and wonder woman actually survive the amount of loved ones, and oakley bull as far outweighs it bundles several positive messages related to go. Like just: Like Loading. Imdb all but see virtue you Zahnarztpraxis Honar & Bromand Berlin. Took so it is wonder parents guide items below. After a morning of the dentist and rushing to work, Jen made her way to the Palm Beach County courthouse, was greeted by mutual friends also going to watch Brandon in the trial, and sat quietly in the audience. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

A Parent's Guide to Instagram

A PARENT’S GUIDE TO INSTAGRAM AUSTRALIAN EDITION 2019 In partnership with 1 A Parent’s Guide to Instagram A LETTER FROM REACHOUT An introduction to supporting your teen on Instagram ReachOut is Australia’s leading mental health and wellbeing organisation for young people and their parents. We know from research that parents and carers are worried about their children using social media. We understand that it can feel overwhelming to keep on top of what your child is accessing, and to manage how much time they’re spending online. At the same time, being socially connected is very important for your child’s development, and social media is part of socialising and connecting with others today. Teenagers regularly use social media to bond with friends, keep up with their peers, meet new people, and learn about world events and current affairs outside of their immediate life. Like any form of social engagement, social media comes with risks. Some of the most common of these include spending too much time online and being disconnected from the real world, being affected by online bullying, sharing intimate photos, and having reduced self-esteem from judging oneself or one’s own life negatively by comparison with others’ ‘ideal’ lives as shown online on sites such as Instagram. 22 The good news is, there are things you and your child can do to reduce these risks and enjoy participating in the online world. This guide will help you to understand Instagram and provide practical tips on how to start a conversation with your young person about managing their privacy, comments and time online. -

Le Harcèlement Sexuel : Clarification

Université de Montréal L’évolution des représentations des crimes sexuels et du harcèlement sexuel dans les téléséries américaines de fiction post #Metoo. Par Françoise Goulet-Pelletier Département d’histoire de l’art et d’études cinématographiques Faculté des arts et des sciences Mémoire présenté à la Faculté des études supérieures et postdoctorales en vue de l’obtention du grade de M.A. en études cinématographiques, option recherche. Décembre 2019 © Françoise Goulet-Pelletier, 2019 ii Université de Montréal Unité académique : Département d’histoire de l’art et d’études cinématographiques Ce mémoire intitulé L’évolution des représentations des crimes sexuels et du harcèlement sexuel dans les téléséries américaines post #Metoo. Présenté par Françoise Goulet-Pelletier A été évalué par un jury composé des personnes suivantes Isabelle Raynauld Directrice de recherche Marta Boni Membre du jury Stéfany Boisvert Membre du jury iii Résumé Le mouvement social #Metoo a bouleversé les mœurs et les façons de penser quant aux enjeux liés au harcèlement sexuel et aux abus sexuels. En effet, en automne 2017, une vague de dénonciations déferle sur la place publique et peu à peu, les frontières de ce qui est acceptable ou pas semblent se redéfinir au sein de plusieurs sociétés. En partant de cette constatation sociétale, nous avons cru remarquer une reprise des enjeux entourant le mouvement social #Metoo dans les séries télévisées américaines de fiction. Ce mémoire souhaite illustrer et analyser l’évolution des représentations des crimes sexuels et du harcèlement sexuel inspirée par le mouvement #Metoo. En reprenant les grandes lignes de ce mouvement, cette étude s’attarde sur son impact sur la société nord-américaine. -

Imdb's Ios and ANDROID APPS HAVE NOW BEEN DOWNLOADED MORE THAN 50 MILLION TIMES

IMDb’S iOS AND ANDROID APPS HAVE NOW BEEN DOWNLOADED MORE THAN 50 MILLION TIMES Just-Launched Redesign of IMDb’s Movies & TV App for iPad Includes Discovery Features, Personalized Recommendations and Watchlist Enhancements IMDb’s Portfolio of Leading Mobile Entertainment Apps Achieved Significant Milestones and Garnered Media Acclaim in 2012 SEATTLE, WA. – December 20, 2012—IMDb, the world’s most popular and authoritative source for movie, TV and celebrity content, today announced that its award-winning Movies & TV apps for iOS and Android have each been downloaded more than 25 million times for a total of more than 50 million combined user downloads. Over the last 5 months, IMDb’s mobile-optimized website and apps have received an average of more than 175 million visits per month. Additionally, IMDb just launched a redesigned version of its acclaimed iPad app featuring highly anticipated discovery features, personalized recommendations and Watchlist enhancements. To learn more and download IMDb’s free apps, go to: http://www.imdb.com/apps/ “2012 has been a significant year for innovation and usage of IMDb’s leading mobile apps for iOS, Android and Kindle Fire,” said Col Needham, IMDb’s founder and CEO. “Our mission is to continually surprise and delight our customers with new features that will revolutionize the movie-watching experience such as ‘X-Ray for Movies,’ which we launched in September 2012 exclusively on the new Kindle Fire HD devices. We look forward to raising the bar on behalf of our customers in 2013.” IMDb’s iPad App Redesign Beginning today, an update (available through the iTunes App Store) to IMDb’s popular iPad app includes a complete redesign focused on discovery features, personalized recommendations and Watchlist enhancements. -

Recommend Me a Movie on Netflix

Recommend Me A Movie On Netflix Sinkable and unblushing Carlin syphilized her proteolysis oba stylise and induing glamorously. Virge often brabble churlishly when glottic Teddy ironizes dependably and prefigures her shroffs. Disrespectful Gay symbolled some Montague after time-honoured Matthew separate piercingly. TV to find something clean that leaves you feeling inspired and entertained. What really resonates are forgettable comedies and try making them off attacks from me up like this glittering satire about a writer and then recommend me on a netflix movie! Make a married to. Aldous Snow, she had already become a recognizable face in American cinema. Sonic and using his immense powers for world domination. Clips are turning it on surfing, on a movie in its audience to. Or by his son embark on a movie on netflix recommend me of the actor, and outer boroughs, leslie odom jr. Where was the common cut off point for users? Urville Martin, and showing how wealth, gives the film its intended temperature and gravity so that Boseman and the rest of her band members can zip around like fireflies ambling in the summer heat. Do you want to play a game? Designing transparency into a recommendation interface can be advantageous in a few key ways. The Huffington Post, shitposts, the villain is Hannibal Lector! Matt Damon also stars as a detestable Texas ranger who tags along for the ride. She plays a woman battling depression who after being robbed finds purpose in her life. Netflix, created with unused footage from the previous film. Selena Gomez, where they were the two cool kids in their pretty square school, and what issues it could solve. -

Thrill of the Chace

REVIEW Ed and Thrill of Jessica are dating in real life KELLY RUTHERFORD CE (Lily van der Woodsen) It’s a case of life imitating THELUCKY SHANNON O’M EARACHA KEEPS A DATE Ed and art as 40-year-old WITH GOSSIP GIRL NICE GUY NATE Chace are Kelly, who plays a great mates multi-divorced mum, off-screen battles for custody of her WAKE-UP call at 6am is not real-life son, Hermès. much fun, although if Chace ED WESTWICK Crawford – Gossip Girl’s Nate (Chuck A Bass), CHACE CRAWFORD Archibald – is at the end of the line, (Nate Archibald) and JESSICA could there be a better reason to get SZOHR (Vanessa Abrams) up in the morning? Nate and Vanessa briefly dated on So Grazia happily (and breathlessly) the show, but party-boy Ed is now takes the call from the Texan romancing Jessica in the real world – heart-throb, who has a rare day off despite the gay rumours that plague former flatmates Ed and Chace. from !lming the hit drama series. The 23-year-old is eager to tell us about his crush on Australia and his penchant for Aussie stars. “I want to get to Australia so bad,” Chace says. “Ed [Westwick, aka Chuck Bass] has of the been down there and he had a blast. Real-life drama s Australia is de!nitely next on my list. The accent, the girls!” CAST Despite having hordes of female GOSSIP GI RL fans, the actor remains surprisingly THE ON-SCREEN SOAP OPERA HAS grounded, mostly thanks to some NOTHING ON THEIR OFF-SCREEN PLOTS good ole southern values. -

Official Sweepstakes Rules

OFFICIAL SWEEPSTAKES RULES A PURCHASE IS NECESSARY TO ENTER OR WIN. VOID WHERE PROHIBITED. IGN Summer of Games Fundraiser Sweepstakes (the “Sweepstakes”) is governed by these official rules (the “Sweepstakes Rules”). The Sweepstakes begins on June 9, 2020 at 9 AM PST and ends on June 30, 2020 at 11:59 PM PST (the “Sweepstakes Period”). SPONSOR: IGN Entertainment, Inc. with an address of 625 2nd Street, San Francisco Ca, 94107 (the “Sponsor”). ELIGIBILITY: This Sweepstakes is open to individuals who are eighteen (18) years of age or older at the time of entry who are legal residents of the fifty (50) United States of America or the District of Columbia. By entering the Sweepstakes as described in these Sweepstakes Rules, entrants represent and warrant that they are complying with these Sweepstakes Rules (including, without limitation, all eligibility requirements), and that they agree to abide by and be bound by all the rules and terms and conditions stated herein and all decisions of Sponsor, which shall be final and binding. All previous winners of any sweepstakes sponsored by Sponsor during the nine (9) month period prior to the Selection Date are not eligible to enter. Any individuals (including, but not limited to, employees, consultants, independent contractors and interns) who have, within the past six (6) months, held employment with or performed services for Sponsor or any organizations affiliated with the sponsorship, fulfillment, administration, prize support, advertisement or promotion of the Sweepstakes (“Employees”) are not eligible to enter or win. Immediate Family Members and Household Members are also not eligible to enter or win. -

SAFER at HOME in Select Theaters, VOD & Digital on February 26, 2021

SAFER AT HOME In Select Theaters, VOD & Digital on February 26, 2021 DIRECTED BY Will Wernick WRITTEN BY Will Wernick, Lia Bozonelis PRODUCED BY Will Wernick, John Ierardi, Bo Youngblood, Lia Bozonelis (Co-Producer), Jason Phillips (Co-Producer) STARRING Jocelyn Hudon, Emma Lahana, Alisa Allapach, Adwin Brown, Dan J. Johnson, Michael Kupisk, Daniel Robaire RUN TIME: 82 mins DISTRIBUTED BY: Vertical Entertainment For additional information please contact: LA Daniel Coffey – [email protected] Emily Maroon – [email protected] NY Susan Engel – [email protected] Danielle Borelli – [email protected] ABOUT THE FILM Synopsis Two years into the pandemic, a group of friends throw an online party with a night of games, drinking and drugs. After taking an ecstasy pill, things go terribly wrong and the safety of their home becomes more terrifying than the raging chaos outside. Director’s Statement Making Safer at Home was challenging. Not just because of the technical hurdles the pandemic mandated, but because of the strange new features life had taken on in those early months of the pandemic. I found myself having unusual conversations, and realizations about myself and friends — things that only this type of stress could bring out. I noticed people making major, sometimes life changing decisions, quickly. Brake-ups, pregnancies, divorces, fights-- this instigated them all. Almost everyone I knew was caught in an indefinite cycle of every day feeling the same. And then we started working on this film. Safer at Home plays out essentially in real time, and shows what a long period of lockdown could do to a group of friends.