Rainbow Trout and Steelhead

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

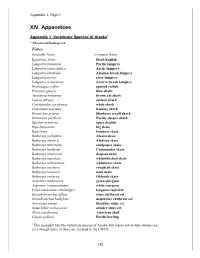

XIV. Appendices

Appendix 1, Page 1 XIV. Appendices Appendix 1. Vertebrate Species of Alaska1 * Threatened/Endangered Fishes Scientific Name Common Name Eptatretus deani black hagfish Lampetra tridentata Pacific lamprey Lampetra camtschatica Arctic lamprey Lampetra alaskense Alaskan brook lamprey Lampetra ayresii river lamprey Lampetra richardsoni western brook lamprey Hydrolagus colliei spotted ratfish Prionace glauca blue shark Apristurus brunneus brown cat shark Lamna ditropis salmon shark Carcharodon carcharias white shark Cetorhinus maximus basking shark Hexanchus griseus bluntnose sixgill shark Somniosus pacificus Pacific sleeper shark Squalus acanthias spiny dogfish Raja binoculata big skate Raja rhina longnose skate Bathyraja parmifera Alaska skate Bathyraja aleutica Aleutian skate Bathyraja interrupta sandpaper skate Bathyraja lindbergi Commander skate Bathyraja abyssicola deepsea skate Bathyraja maculata whiteblotched skate Bathyraja minispinosa whitebrow skate Bathyraja trachura roughtail skate Bathyraja taranetzi mud skate Bathyraja violacea Okhotsk skate Acipenser medirostris green sturgeon Acipenser transmontanus white sturgeon Polyacanthonotus challengeri longnose tapirfish Synaphobranchus affinis slope cutthroat eel Histiobranchus bathybius deepwater cutthroat eel Avocettina infans blackline snipe eel Nemichthys scolopaceus slender snipe eel Alosa sapidissima American shad Clupea pallasii Pacific herring 1 This appendix lists the vertebrate species of Alaska, but it does not include subspecies, even though some of those are featured in the CWCS. -

RACE Species Codes and Survey Codes 2018

Alaska Fisheries Science Center Resource Assessment and Conservation Engineering MAY 2019 GROUNDFISH SURVEY & SPECIES CODES U.S. Department of Commerce | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration | National Marine Fisheries Service SPECIES CODES Resource Assessment and Conservation Engineering Division LIST SPECIES CODE PAGE The Species Code listings given in this manual are the most complete and correct 1 NUMERICAL LISTING 1 copies of the RACE Division’s central Species Code database, as of: May 2019. This OF ALL SPECIES manual replaces all previous Species Code book versions. 2 ALPHABETICAL LISTING 35 OF FISHES The source of these listings is a single Species Code table maintained at the AFSC, Seattle. This source table, started during the 1950’s, now includes approximately 2651 3 ALPHABETICAL LISTING 47 OF INVERTEBRATES marine taxa from Pacific Northwest and Alaskan waters. SPECIES CODE LIMITS OF 4 70 in RACE division surveys. It is not a comprehensive list of all taxa potentially available MAJOR TAXONOMIC The Species Code book is a listing of codes used for fishes and invertebrates identified GROUPS to the surveys nor a hierarchical taxonomic key. It is a linear listing of codes applied GROUNDFISH SURVEY 76 levelsto individual listed under catch otherrecords. codes. Specifically, An individual a code specimen assigned is to only a genus represented or higher once refers by CODES (Appendix) anyto animals one code. identified only to that level. It does not include animals identified to lower The Code listing is periodically reviewed -

61661147.Pdf

Resource Inventory of Marine and Estuarine Fishes of the West Coast and Alaska: A Checklist of North Pacific and Arctic Ocean Species from Baja California to the Alaska–Yukon Border OCS Study MMS 2005-030 and USGS/NBII 2005-001 Project Cooperation This research addressed an information need identified Milton S. Love by the USGS Western Fisheries Research Center and the Marine Science Institute University of California, Santa Barbara to the Department University of California of the Interior’s Minerals Management Service, Pacific Santa Barbara, CA 93106 OCS Region, Camarillo, California. The resource inventory [email protected] information was further supported by the USGS’s National www.id.ucsb.edu/lovelab Biological Information Infrastructure as part of its ongoing aquatic GAP project in Puget Sound, Washington. Catherine W. Mecklenburg T. Anthony Mecklenburg Report Availability Pt. Stephens Research Available for viewing and in PDF at: P. O. Box 210307 http://wfrc.usgs.gov Auke Bay, AK 99821 http://far.nbii.gov [email protected] http://www.id.ucsb.edu/lovelab Lyman K. Thorsteinson Printed copies available from: Western Fisheries Research Center Milton Love U. S. Geological Survey Marine Science Institute 6505 NE 65th St. University of California, Santa Barbara Seattle, WA 98115 Santa Barbara, CA 93106 [email protected] (805) 893-2935 June 2005 Lyman Thorsteinson Western Fisheries Research Center Much of the research was performed under a coopera- U. S. Geological Survey tive agreement between the USGS’s Western Fisheries -

And Chinook Salmon Age Structure

Exploring the potential role of late stage predation and Chinook salmon age structure Item Type Thesis Authors Manishin, Kaitlyn A. Download date 28/09/2021 05:14:32 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/10301 EXPLORING THE POTENTIAL ROLE OF LATE STAGE PREDATION AND CHINOOK SALMON AGE STRUCTURE By Kaitlyn A. Manishin A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Fisheries University of Alaska Fairbanks December 2018 APPROVED: Andrew C. Seitz, Committee Chair Peter A.H. Westley, Committee Member Curry J. Cunningham, Committee Member Kenneth J. Goldman, Committee Member Milo D. Adkison, Chair Department of Fisheries S. Bradley Moran, Dean College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences Michael A. Castellini, Dean of the Graduate School Abstract Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) populations across the North Pacific have displayed a decrease in body size-at-return resulting from declines both in age- and body size-at-maturity. These changes have precipitated the loss of the oldest age classes in some populations and have occurred throughout the range of this species, suggesting a shared - yet currently unknown - driver in the common marine environment. A hypothesis for the cause of these changes is intense and/or selective predation marine mortality after the first winter in the ocean, potentially from predators selectively removing relatively large sub-adult Chinook salmon. Here I consider the question: under what circumstances could predation on large sub-adult individuals by salmon sharks (Lamna ditropis) change the age structure of a Chinook salmon population? To address this question, I first estimated total per capita prey consumption by salmon sharks - an increasingly acknowledged predator of salmon on the high seas - using three methods: 1) daily ration requirement, 2) bioenergetic mass balance, 3) and a von Bertalanffy growth model. -

The Natural Resources of Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary

Marine Sanctuaries Conservation Series ONMS-13-05 The Natural Resources of Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary: A Focus on Federal Waters Final Report June 2013 U.S. Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Ocean Service Office of National Marine Sanctuaries June 2013 About the Marine Sanctuaries Conservation Series The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Ocean Service (NOS) administers the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries (ONMS). Its mission is to identify, designate, protect and manage the ecological, recreational, research, educational, historical, and aesthetic resources and qualities of nationally significant coastal and marine areas. The existing marine sanctuaries differ widely in their natural and historical resources and include nearshore and open ocean areas ranging in size from less than one to over 5,000 square miles. Protected habitats include rocky coasts, kelp forests, coral reefs, sea grass beds, estuarine habitats, hard and soft bottom habitats, segments of whale migration routes, and shipwrecks. Because of considerable differences in settings, resources, and threats, each marine sanctuary has a tailored management plan. Conservation, education, research, monitoring and enforcement programs vary accordingly. The integration of these programs is fundamental to marine protected area management. The Marine Sanctuaries Conservation Series reflects and supports this integration by providing a forum for publication and discussion of the complex issues currently facing the sanctuary system. Topics of published reports vary substantially and may include descriptions of educational programs, discussions on resource management issues, and results of scientific research and monitoring projects. The series facilitates integration of natural sciences, socioeconomic and cultural sciences, education, and policy development to accomplish the diverse needs of NOAA’s resource protection mandate. -

Predation on Fraser River Sockeye Salmon Villy Christensen and Andrew W

February 2011 technical report 8 Predation on Fraser River Sockeye Salmon Villy Christensen and Andrew W. Trites The Cohen Commission of Inquiry into the Decline of Sockeye Salmon in the Fraser River Predation on Fraser River Sockeye Salmon Villy Christensen and Andrew W. Trites Fisheries Centre, University of British Columbia 2202 Main Mall Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4 Technical Report 8 February 2011 Recommended citation for this report: Christensen, V. and A.W. Trites. 2011. Predation on Fraser River sockeye salmon. Cohen Commission Tech. Rept. 8:129p. Vancouver, B.C. www.cohencommission.ca Preface Fraser River sockeye salmon are vitally important for Canadians. Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities depend on sockeye for their food, social, and ceremonial purposes; recreational pursuits; and livelihood needs. They are key components of freshwater and marine aquatic ecosystems. Events over the past century have shown that the Fraser sockeye resource is fragile and vulnerable to human impacts such as rock slides, industrial activities, climatic change, fisheries policies and fishing. Fraser sockeye are also subject to natural environmental variations and population cycles that strongly influence survival and production. In 2009, the decline of sockeye salmon stocks in the Fraser River in British Columbia led to the closure of the fishery for the third consecutive year, despite favourable pre-season estimates of the number of sockeye salmon expected to return to the river. The 2009 return marked a steady decline that could be traced back two decades. In November 2009, the Governor General in Council appointed Justice Bruce Cohen as a Commissioner under Part I of the Inquiries Act to investigate this decline of sockeye salmon in the Fraser River. -

The Etyfish Project © Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J

AULOPIFORMES · 1 The ETYFish Project © Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J. Lazara COMMENTS: v. 18.0 - 24 Aug. 2020 Infracohort EURYPTERYGIA eurys, wide; pteron, fin or wing; proposed by Rosen (1973) but allusion not explained, possibly referring to better-developed fins (with spiny rays) compared to soft-rayed fins of Stomiiformes, which he placed in Stenopterygia (stenos, narrow), then presumed to be the more primitive sister group of neoteleosteans Section CYCLOSQUAMATA cyclo-, cycloid; squamata, scaled, referring to predominance of cycloid scales among its taxa, compared to the Ctenosquamata, in which ctenoid scales predominate Order AULOPIFORMES 16 families · 50 genera/subgenera · 296 species/subspecies Suborder AULOPOIDEI Family SYNODONTIDAE Lizardfishes 4 genera · 83 species Subfamily Synodontinae Lizardfishes Synodus Scopoli 1777 tautonymous with Esox synodus (see S. synodus for an explanation of this ancient and enigmatic name) Synodus binotatus Schultz 1953 bi-, two; notatus, marked, referring to two black spots at tip of snout Synodus bondi Fowler 1939 in honor of ornithologist James Bond (1900-1989), Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, who collected type (historical footnote: Bond’s name was appropriated by writer Ian Fleming for his fictional spy, 007 James Bond) Synodus capricornis Cressey & Randall 1978 -is, genitive singular of: Capricorn, referring to type locality near the Tropic of Capricorn Synodus dermatogenys Fowler 1912 dermatos, skin; genys, cheek, referring to scaleless lower cheek Synodus doaki Russell -

XIV. Appendices

Appendix 1, Page 1 XIV. Appendices Appendix 1. Vertebrate Species of Alaska1 * Threatened/Endangered Fishes Scientific Name Common Name Eptatretus deani black hagfish Lampetra tridentata Pacific lamprey Lampetra camtschatica Arctic lamprey Lampetra alaskense Alaskan brook lamprey Lampetra ayresii river lamprey Lampetra richardsoni western brook lamprey Hydrolagus colliei spotted ratfish Prionace glauca blue shark Apristurus brunneus brown cat shark Lamna ditropis salmon shark Carcharodon carcharias white shark Cetorhinus maximus basking shark Hexanchus griseus bluntnose sixgill shark Somniosus pacificus Pacific sleeper shark Squalus acanthias spiny dogfish Raja binoculata big skate Raja rhina longnose skate Bathyraja parmifera Alaska skate Bathyraja aleutica Aleutian skate Bathyraja interrupta sandpaper skate Bathyraja lindbergi Commander skate Bathyraja abyssicola deepsea skate Bathyraja maculata whiteblotched skate Bathyraja minispinosa whitebrow skate Bathyraja trachura roughtail skate Bathyraja taranetzi mud skate Bathyraja violacea Okhotsk skate Acipenser medirostris green sturgeon Acipenser transmontanus white sturgeon Polyacanthonotus challengeri longnose tapirfish Synaphobranchus affinis slope cutthroat eel Histiobranchus bathybius deepwater cutthroat eel Avocettina infans blackline snipe eel Nemichthys scolopaceus slender snipe eel Alosa sapidissima American shad Clupea pallasii Pacific herring 1 This appendix lists the vertebrate species of Alaska, but it does not include subspecies, even though some of those are featured in the CWCS. -

Annotated Checklist of Fishes from Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary with Notes on Extralimital Species

ISSN 1313-2970 (online) ISSN 1313-2989 (print) A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 887 2019 Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary (MBNMS), a federal marine protected area located off central California, is host to a diverse fish fauna occupying a variety of habitats. The rich history of ichthyological research and surveys off central California provide a wealth of information to ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF construct the first inventory of fishes occurring within MBNMS. FISHES FROM MONTEREY BAY Critical analyses of material from ichthyological collections at natural NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY history museums, the literature, and visual records were critical in creating WITH NOTES ON an annotated checklist of fishes occurring within MBNMS. The checklist EXTRALIMITAL SPECIES presented herein provides sources of basis, occurrence of fishes during cold- or warm-water events, records of historically occurring fishes, special BY places of occurrence (i.e., Davidson Seamount, Elkhorn Slough), introduced ERICA J. BURTON, RObeRT N. LEA species, and reference to original species descriptions from within MBNMS. Geographical errors in the literature based on misidentifications in the field are noted. This inventory provides evidence of occurrence for 507 fishes within MBNMS and an additional 18 species considered to be extralimital. This annotated checklist of fishes can be used by those interested in zoogeography, marine protected areas, ichthyology, regional natural history, and sanctuary management. ZooKeys 887 2019 http://zookeys.pensoft.net Special Issue ! http://zookeys.pensoft.net AUTHOR GUIDELINES Accepted Papers: Same as above, but are not limited to: Authors are kindly requested to sub- but ‘’In press’’ appears instead the • Zoobank (www.zoobank.org), mit their manuscript only through page numbers. -

GLD for Marine Renewable Energy

AGENDA ITEM 15 MAY 20-21, 2021-LCDC MEETING ATTACHMENT A STATE OF OREGON GEOGRAPHIC LOCATION DESCRIPTION Analysis of Reasonably Foreseeable Effects of Federal Actions Related to Marine Renewable Energy Projects on Resources and Uses Occurring within the Federal Waters of the Oregon Ocean Stewardship Area. Oregon Department of Land Conservation and Development Coastal Management Program (March 20, 2015) This document, pursuant to 15 C.F.R. § 930.53, describes a geographic area in federal waters where certain federal license or permit activities, under 15 C.F.R. Part 930, Subpart D, and Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) authorizations, under 15 C.F.R. Part 930, Subpart E, will be subject to review by the Oregon Coastal Management Program (OCMP) under the Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA) Federal Consistency Provision. The OCMP is seeking federal consistency review over certain federal actions listed below, taking place in the federal waters within a part of the Oregon Ocean Stewardship Area (OSA), as described in Oregon’s Statewide Planning Goal 19 Ocean Resources. That area will be delineated as the Geographic Location Description and will hereafter be referred to as the GLD. The document consists of the following parts: (I) a description of the specific geographic location within federal waters to which it applies, including a brief description of the types of marine renewable energy uses that are anticipated; (II) a list of federal license or permit activities and OCS authorizations related to marine renewable energy development that will be subject to OCMP review when the federal action or activity that is being proposed is located within the geographic area; and (III) an analysis of the reasonably foreseeable effects the activity may have on specific marine resources and uses within Oregon’s coastal zone. -

Eastern Gulf of Alaska Ecosystem Assessment, July Through August 2017

NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-AFSC-367 doi:10.7289/V5/TM-AFSC-367 Eastern Gulf of Alaska Ecosystem Assessment, July through August 2017 W. W. Strasburger, J. H. Moss, K. A. Siwicke, E. M. Yasumiishi, A. I. Pinchuk, and K. H. Fenske U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service Alaska Fisheries Science Center February 2018 NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS The National Marine Fisheries Service's Alaska Fisheries Science Center uses the NOAA Technical Memorandum series to issue informal scientific and technical publications when complete formal review and editorial processing are not appropriate or feasible. Documents within this series reflect sound professional work and may be referenced in the formal scientific and technical literature. The NMFS-AFSC Technical Memorandum series of the Alaska Fisheries Science Center continues the NMFS-F/NWC series established in 1970 by the Northwest Fisheries Center. The NMFS-NWFSC series is currently used by the Northwest Fisheries Science Center. This document should be cited as follows: Strasburger, W. W., J. H. Moss, K. A. Siwicke, E. M. Yasumiishi, A. I. Pinchuk, and K H. Fenske. 2018. Eastern Gulf of Alaska Ecosystem Assessment, July through August 2017. U.S. Dep. Commer., NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-AFSC-367, 105 p. Document available: http://www.afsc.noaa.gov/Publications/AFSC-TM/NOAA-TM-AFSC-367.pdf Reference in this document to trade names does not imply endorsement by the National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-AFSC-367 doi:10.7289/V5/TM-AFSC-367 Eastern Gulf of Alaska Ecosystem Assessment, July through August 2017 by W. -

The Global Status and Conservation of Oceanic Pelagic Sharks and Rays

AQUATIC CONSERVATION: MARINE AND FRESHWATER ECOSYSTEMS Aquatic Conserv: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. (2008) Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com) DOI: 10.1002/aqc.975 You can swim but you can’t hide: the global status and conservation of oceanic pelagic sharks and rays NICHOLAS K. DULVYa,*, JULIA K. BAUMb, SHELLEY CLARKEc, LEONARD J. V. COMPAGNOd, ENRIC CORTE´Se, ANDRE´S DOMINGOf, SONJA FORDHAMg, SARAH FOWLERh, MALCOLM P. FRANCISi, CLAUDINE GIBSONh, JIMMY MARTI´NEZj, JOHN A. MUSICKk, ALEN SOLDOl, JOHN D. STEVENSm and SARAH VALENTIh a Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science, Lowestoft Laboratory, Lowestoft, NR33 0HT, UK and Department of Biological Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC V5A 1S5, Canada b Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, California 92093-0202, USA c Division of Biology, Imperial College London, Silwood Park Campus, Manor House, Buckhurst Road, Ascot, Berkshire SL5 7PY, UK d Shark Research Center, Iziko } South African Museum, P.O. Box 61, Cape Town, 8000 South Africa e NOAA Fisheries Service, Panama City Laboratory, Panama City, FL 32408, USA f Direccio´n Nacional de Recursos Acua´ticos, Recursos Pela´gicos, Constituyente 1497, CP 11200, Montevideo, Uruguay g Ocean Conservancy and Shark Alliance, c/o Oceana, Rue Montoyer, 39 1000 Brussels, Belgium h IUCN SSC Shark Specialist Group, Naturebureau International, 36 Kingfisher Court, Hambridge Road, Newbury, RG14 5SJ, UK i National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, Private Bag 14901, Wellington, New Zealand j Escuela de Pesca del Pacifico Oriental (EPESPO). Los Esteros, Avenida 102 y calle 124, P.O.