Tiny Teacups Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D-Day the Invasion

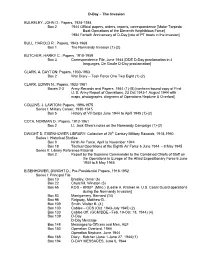

D-Day – The Invasion BULKELEY, JOHN D.: Papers, 1928-1984 Box 2 1944 Official papers, orders, reports, correspondence [Motor Torpedo Boat Operations of the Eleventh Amphibious Force] 1984 Fortieth Anniversary of D-Day [role of PT boats in the invasion] BULL, HAROLD R.: Papers, 1943-1968 Box 1 The Normandy Invasion (1)-(2) BUTCHER, HARRY C.: Papers, 1910-1959 Box 3 Correspondence File, June 1944 [DDE D-Day proclamation in 4 languages, De Gaulle D-Day proclamation] CLARK, A. DAYTON: Papers, 1930-1963 Box 2 War Diary – Task Force One Two Eight (1)-(2) CLARK, EDWIN N.: Papers, 1933-1981 Boxes 2-3 Army Records and Papers, 1944 (1)-(8) [contains bound copy of First U. S. Army Report of Operations, 23 Oct.1943-1 August 1944 with maps, photographs, diagrams of Operations Neptune & Overlord] COLLINS, J. LAWTON: Papers, 1896-1975 Series I: Military Career, 1930-1945 Box 5 History of VII Corps June 1944 to April 1945 (1)-(2) COTA, NORMAN D.: Papers, 1912-1961 Box 2 Lt. Jack Shea’s notes on the Normandy Campaign (1)-(2) DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY: Collection of 20th Century Military Records, 1918-1950 Series I: Historical Studies Box 9 Ninth Air Force, April to November 1944 Box 18 Tactical Operations of the Eighth Air Force 6 June 1944 – 8 May 1945 Series II: Library Reference Material Box 2 Report by the Supreme Commander to the Combined Chiefs of Staff on the Operations in Europe of the Allied Expeditionary Force 6 June 1944 to 8 May 1945 EISENHOWER, DWIGHT D.: Pre-Presidential Papers, 1916-1952 Series I: Principal File Box 13 Bradley, Omar (6) Box 22 Churchill, Winston (5) Box 65 KOS – KREP (Misc.) [Leslie A. -

The Hobson Incident

The Hobson Incident Late on Saturday night, April 26, 1952, U.S.S. Wasp was completing night maneuvers some 1,200 miles east of New York. She turned into the wind to recover her aircraft. The skipper of the USS Hobson, a destroyer-minesweeper, apparently became confused in the dark and made a few turns that ended with the Hobson cutting in front of Wasp. The Wasp cut the Hobson in two. From there, it rapidly got worse. The Hobson was hit aft of midship, and the entire ship sank in four minutes. Her captain and 174 other men were lost. In rolling over, Hobson’s keel sliced off an 80-ton section of Wasp’s bow, from keel to about waterline, the section being carried away, with interior deck levels, oil tanks, fittings, and gears. Those men from the Hobson who were fortunate enough to be thrown clear and rescued were covered with oil from Wasp’s broken tanks. Fortunately, there were no crew quarters located in Wasp’s bow, and Wasp, in fact, suffered no casualties in the affair. Wasp had been under orders to relieve the carrier Tarawa farther east. Her bulkheads holding against the open bow, she turned for repairs at New York. Proceeding at a ten-knot speed, often reduced to near zero when heavy going forced her to proceed stern-first, she almost lost her two anchor chains ($40,000 each). Wasp, drydock-free by May 19, then ammunitioned and service fitted, was back on sea duty in less than five weeks, a record for major ship repairs. -

USS Stoddard Alumni Newsletter—January 2017 Page 2

Website: www.ussstoddard.org USS STODDARD Date: January 15th, 2017 ALUMNI NEWSLETTER USS STODDARD DD566 WWII * Korea * Vietnam 29th Reunion—New Orleans, Louisiana Crowne Plaza 2829 Williams Blvd. September 20th – September 23rd - 2017 Kenner, LA 70062 Hosts: John & Carlene Rauh Email: [email protected] Room Rate: $115.00 Two Days Before & After Reunion We welcome everyone to a place where centuries old architec- Breakfast ture is the backdrop for a culture to arouse your spirit. The city Restaurant of New Orleans is a magical place to explore. Enjoy the history, Free Parking food, and historical sites. Free Internet Airport Shuttle The National WWII Museum is considered one of the top museums Reservation the nation. It tells the story of the American Experience in the war information— that changed the world. The movie see page 8 “Beyond All Boundaries” is a 4D journey through the war narrated by Tom Hanks. Inside this issue: The French Quarter, also known as the Vieuz Carre, is the oldest 2017 New Orleans 2 neighborhood in the city of New Or- leans founded in 1718. Most of the Portland Reunion 3 & 4 historic buildings were constructed Hobson Accident 5 & 6 in the late Tom Davis Poem 7 18th cen- Annual Meeting 8 tury dur- ing the Hotel Info 8 Spanish rule or built during the first Chaplain’s Report 9 half of the 19th century, after U.S. an- Directory Update 9 nexation. The district has been desig- Ship’s Store 10 nated as a National Historic Landmark. USS Stoddard Alumni Newsletter—January 2017 Page 2 NATCHEZ Jazz Dinner Cruise. -

Military History Anniversaries 16 Thru 30 April

Military History Anniversaries 16 thru 30 April Events in History over the next 15 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Apr 16 1738 – American Revolution: Blamed for the loss of the 13 colonies » Henry Clinton, the future commander in chief of British forces charged with suppressing the rebellion in North America, is born in Newfoundland, Canada. Henry Clinton Henry Clinton’s father, George, was the royal governor of Newfoundland at the time of his birth. He was made the royal governor of New York in 1743, and Henry spent eight years in that colony before moving to England and taking a military commission in the Coldstream Guards in 1751. By 1758, Henry Clinton had earned the rank of lieutenant colonel in the Grenadier Guards. He continued to distinguish himself as a soldier during the Seven Years’ War and, in 1772, achieved two significant feats for a man born in the colonies–the rank of major general in the British army and a seat in Parliament. Clinton’s part in the War of American Independence began auspiciously. He arrived with Major General William Howe and, after the draw at Bunker Hill, served in the successful capture of New York City and the Battle of Long Island, which earned him the rank of lieutenant general and membership in the Most Honourable Order of Bath as a KCB, or Knight Commander of the British Empire, which conferred to him the title of Sir. After Howe performed poorly at Saratoga and was demoted, Clinton was promoted to commander in chief of Britain’s North American forces in 1778. -

Hobson: Unsung Hero

USS Hobson (DD-464) on 4 March 1942 off Charleston, South U Carolina. At this time, the destroyer was finished in Camouflage Measure 12 (Modified). As typical of the time S period, the ship photo has been censored to remove radar SHOBSON antenna and the Mk. 37 gun director. She served in every major US Naval n 12 May 1952, LIFE magazine carried a UnsungHthree-page storyero headed “Wasp Splits the action of the European and in the last OHobson.” Illustrated with a drawing of a carrier ramming a smaller ship and photos of oil-blackened great action of the Pacific. She even survivors, it detailed a disaster off the Azores where the survived a kamikaze attack. Still, the 27,000-ton Wasp collided with the 1600-ton Hobson. Life also mentioned the fact that Wasp had been a destroyer USS Hobson received little veteran of the Pacific Theater in the Second World War. But it made no mention of the Hobson’s record. public acclaim — until she was sliced In fact, the Hobson had served in every major US through by the aircraft carrier USS Wasp naval action of the European War and in the last great action of the Pacific. She had been hit by a kamikaze and survived. And she had six Battle Stars BY CHARLES M. ROBINSON III and a Presidential Unit Citation. INTO SERVICE The Hobson was built as DD-464 and named after The Hobson left Bermuda on 25 October escorting On D-Day, 8 November, the Ranger’s group arrived R/Adm. Richmond P. -

Naval Accidents 1945-1988, Neptune Papers No. 3

-- Neptune Papers -- Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945 - 1988 by William M. Arkin and Joshua Handler Greenpeace/Institute for Policy Studies Washington, D.C. June 1989 Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945-1988 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Overview ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Nuclear Weapons Accidents......................................................................................................... 3 Nuclear Reactor Accidents ........................................................................................................... 7 Submarine Accidents .................................................................................................................... 9 Dangers of Routine Naval Operations....................................................................................... 12 Chronology of Naval Accidents: 1945 - 1988........................................................................... 16 Appendix A: Sources and Acknowledgements........................................................................ 73 Appendix B: U.S. Ship Type Abbreviations ............................................................................ 76 Table 1: Number of Ships by Type Involved in Accidents, 1945 - 1988................................ 78 Table 2: Naval Accidents by Type -

THE ARMED FORCES OFFICER by Richard M

THE ARMED FORCES OFFICER by Richard M. Swain and Albert C. Pierce The Armed Forces Officer THE ARMED FORCES OFFICER by Richard M. Swain and Albert C. Pierce National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. 2017 Published in the United States by National Defense University Press. Portions of this book may be quoted or reprinted without permission, provided that a standard source credit line is included. NDU Press would appreciate a courtesy copy of reprints or reviews. Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record of this publication may be found at the Library of Congress. Book design by Jessica Craney, U.S. Government Printing Office, Creative Services Division Published by National Defense University Press 260 Fifth Avenue (Building 64) Suite 2500 Fort Lesley J. McNair Washington, DC 20319 U.S. GOVERNMENT OFFICIAL EDITION NOTICE Use of ISBN This is the official U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identified to certify its authenticity. Use of 978-0-16-093758-3 is for the U.S. Government Publishing Office Edition only. The Superintendent of Documents of the U.S. Government Publishing Office requests that any reprinted edition clearly be labeled as a copy of the authentic work with a new ISBN. Contents FOREWORD by General Joseph F. Dunford, Jr., U.S. Marine Corps, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff ...............................................................................ix PREFACE by Major General Frederick M. -

World War II Participants and Contemporaries: Papers

World War II Participants and Contemporaries: Papers Container List ACCETTA, DOMINICK Residence: Fort Lee, New Jersey Service: 355th Inf Regt, Europe Volume: -1" Papers (1)(2) [record of Cannon Co., 355th Inf. Regt., 89th Inf. Div., Jan.-July 1945; Ohrdruf Concentration Camp; clippings; maps; booklet ”The Story of the 89th Infantry Division;” orders; song; ship’s newspaper, Jan. 1946;map with route of 89th Div.] AENCHBACHER, A.E. "Gene" Residence: Wichita, Kansas Service: Pilot, 97th Bomber Group, Europe; flew DDE from Gibraltar to North Africa, November 1942 Volume: -1" Papers [letters; clippings] ALFORD, MARTIN Residence: Abilene, Kansas Service: 5th Inf Div, Europe Volume: -1" Papers [copy of unit newspaper for 5th Inf. Div., May 8, 1945; program for memorial service; statistics on service and casualties in wars and conflicts] ALLMON, WILLIAM B. Residence: Jefferson City, Missouri Service: historian Volume: -1” 104 Inf Div (1) (2) [after action report for November 1944, describing activities of division in southwest Holland; this is a copy of the original report at the National Archives] 1 AMERICAN LEGION NATIONAL HEADQUARTERS Residence: Indianapolis, Indiana Service: Veteran's organization Volume: 13" After the War 1943-45 [a monthly bulletin published by the Institute on Postwar Reconstruction, Aug. 1943-April 1945] American Legion Publications (1)-(11) [civil defense; rights and benefits of veterans; home front; citizenship; universal draft; national defense and security program; Americanism; employment manual; Boy Scouts-youth program; G. I. Bill of Rights; peace and foreign relations; disaster; natural resources; law and order; UMT-universal military training; national defense; veterans’ employment; 1946 survey of veterans; reprint of two pages from The National Legionnaire, June 1940; instructors manual for military drill; United Nations; junior baseball program] Army-Navy YMCA Bulletin, 1942-44 Atlas of World Battle Fronts [1943-45] China at War, 1939 [four issues published by the China Information Publishing Co.] Clippings [submarine war; Alaska; U.S. -

To Read More About Jim Griffiths' U.S. Navy Ships of War Paintings

1 JIM GRIFFITHS -U.S. Navy Ships of War, 1898-1991 (Title/Image Size/Framed Size/Price/Painting Detail-Description) Forty Gouache Paintings depicting important vessels and naval actions from the Spanish American War to the first Iraq conflict. “Across the Sea of Storms” 12 ½” x 19”, 21 x 27”, $4,000 Liberty Ship, 1943 The painting depicts a well-worn Liberty ship plowing through heavy Atlantic seas headed for Europe (Britain) or Russia with much needed war material. In the distance can be seen several other ships in the convoy. While stormy weather was a peril, a greater danger was the threat of a U-boat attack; not until a ship was safely at anchor in port, would this latter threat be put aside but never forgotten. "Always Pushing Forward" 12 1/2 x 19 ¼”, 21 1/4"H x 27 1/4"L, $4,000 BB-40 USS New Mexico 1944 This painting depicts the US. Navy WW II battleship U.S.S. New Mexico (BB-40) at night under a full moon. She is in company with forces that are bound for Mindoro, the Philippines, where she will provide bombardment for the upcoming U.S. landings there sometime in mid-December, 1944. The ship is painted in a camouflage pattern called Ms. 32-6D, a pattern considered the best anti- submarine camouflage. It was designed to be used in areas where visibility was good and where it would be impossible to conceal a ship; at long distances this bold-contrast pattern produced low visibility where the pattern blurred to a uniform shade. -

The USS BRAINE-DD630 Was Laid at the Bath Iron Works on October 12, 1942

USS Braine (DD-630) The keel for the USS BRAINE-DD630 was laid at the Bath Iron Works on October 12, 1942. Accelerated construction continued until launching on March 7, 1943. During the construction period, the assembly of officers and crew began. The first officer to report was Ensign Arthur F. Moricca, a graduate engineer of Rennsalear Polytechnic Institute. The first Commanding Officer, Commander John F. Newman, Jr., USN soon reported to Bath. He was followed by officers Ensign John D. Hotchkiss, Asst. Engineering Officer; Lieutenant John T. Evans, First Lieutenant; Lt(jg) Henry J. Watters, Communications Officer; Ensign William M. Eastman, Supply Officer; Lieutenant George W. Montgomery, Gunnery Officer. The new officers and crew observed the construction of the ship to become familiar with its components and operation. Although it was winter, the crew members enjoyed the serenity of Maine and the delicious sea food served in the many restaurants in the area. On a crisp and breezy winter Maine day with ice still on the river, the sponsor’s party assembled. Mrs. Daniel L. Braine, Brooklyn, New York and wife of the grandson of Admiral Daniel Lawrence Braine, USN for whom the vessel was named, wielded the bottle of champagne. With traditional words, Mrs. Braine christened the new destroyer UNITED STATES SHIP BRAINE - DD630 and launched her into destroyer history. As the ship came to rest in the middle of the Kennebec River, it was obvious that there was still a lot of work to be done before the BRAINE could join the fleet. Installation of boilers, turbines, electric panels, gun mounts, communication and navigation equipment, as well as all the items to accommodate the crew’s living quarters. -

BACKGROUND 6 June Shortly After Midnight the 82Nd and 101St

BACKGROUND The Allies fighting in Normandy were a team of teams – from squads and crews through armies, navies and air forces of many thousands. Click below for maps and summaries of critical periods during their campaign, and for the opportunity to explore unit contributions in greater detail. 6 JUNE ~ D-Day 7-13 JUNE ~ Linkup 14-20 JUNE ~ Struggle In The Hedgerows 21-30 JUNE ~ The Fall Of Cherbourg 1-18 JULY ~ To Caen And Saint-Lô 19-25 JULY ~ Caen Falls 26-31 JULY ~ The Operation Cobra Breakout 1-13 AUGUST ~ Exploitation And Counterattack 14-19 AUGUST ~ Falaise And Orleans 20-25 AUGUST ~ The Liberation Of Paris 6 June Shortly after midnight the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions jumped into Normandy to secure bridgeheads and beach exits in advance of the main amphibious attack. Begin- ning at 0630 the 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions stormed ashore at Omaha Beach against fierce resistance. Beginning at 0700 the 4th Infantry Division overwhelmed less effective opposition securing Utah Beach, in part because of disruption the airborne landings had caused. By day’s end the Americans were securely ashore at Utah and Commonwealth Forces at Gold, Juno and Sword Beaches. The hold on Omaha Beach was less secure, as fighting continued on through the night of 6-7 June. 1 7-13 June The 1st, 2nd and 29th Infantry Divisions attacked out of Omaha Beach to expand the beachhead and link up with their allies. The 1st linked up with the British and pushed forward to Caumont-l’Êventé against weakening resistance. The 29th fought its way south and west and linked up with forces from Utah Beach, while the 2nd attacked alongside both and secured the interval between them. -

Official War Time History of USS Hobson DD-464

Official War Time History of USS Hobson DD-464. Transcribed by CDR Houston H. Stokes from US Navy Records 4/7/2000 from documents dated 16 December 1948 *********************************************************************** Ships Data Section Public Information Division Office of Public Relations HISTORY OF USS HOBSON (DMS 26) ex-(DD 464) Built by the U. S. Navy Yard, Charleston, South Carolina, USS HOBSON's keel was laid on 14 November 1940. The destroyer was launched as DD-464 on 8 September 1941, sponsored by Mrs. Richmond P. Hobson, of New York, New York, widow of Rear Admiral Hobson, USN, in whose honor the ship was named. Admiral Hobson, who died on 16 March 1937, received the Medal of Honor in 1933, "For distinguishing himself conspicuously by extraordinary courage and intrepidity at risk of his life and beyond the call of duty on 3 June 1898, by entering the fortified harbor of Santiago, Cuba, and sinking the partially dismantled collier MERRIMAC in the channel under persistent fire from the enemy fleet and fortifications on shore" during the Spanish-American War. HOBSON was commissioned on 22 January 1942 with Lieutenant Command R. N. McFarlane, USN, as first commanding officer. She held her shakedown off Casco Bay, Maine from 23 April to 3 May 1942. During the war she took part in the following campaigns and engagements: Allied landings at Casablanca, French Morocco - 8 November 1942; carrier strike at Bodo, Norway - October 1943; she sank German submarine (U-575) -13 March 1944; the Allied landings in Normandy, France - 6 June 1944; the Allied landings on Southern France - 15 August 1944; and the American landings on Okinawa - April 1945.