A PUBLICATION of the HAMPTON ROADS NAVAL MUSEUM Volume 23, Issue 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Vietnam War an Australian Perspective

THE VIETNAM WAR AN AUSTRALIAN PERSPECTIVE [Compiled from records and historical articles by R Freshfield] Introduction What is referred to as the Vietnam War began for the US in the early 1950s when it deployed military advisors to support South Vietnam forces. Australian advisors joined the war in 1962. South Korea, New Zealand, The Philippines, Taiwan and Thailand also sent troops. The war ended for Australian forces on 11 January 1973, in a proclamation by Governor General Sir Paul Hasluck. 12 days before the Paris Peace Accord was signed, although it was another 2 years later in May 1975, that North Vietnam troops overran Saigon, (Now Ho Chi Minh City), and declared victory. But this was only the most recent chapter of an era spanning many decades, indeed centuries, of conflict in the region now known as Vietnam. This story begins during the Second World War when the Japanese invaded Vietnam, then a colony of France. 1. French Indochina – Vietnam Prior to WW2, Vietnam was part of the colony of French Indochina that included Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Vietnam was divided into the 3 governances of Tonkin, Annam, and Cochinchina. (See Map1). In 1940, the Japanese military invaded Vietnam and took control from the Vichy-French government stationing some 30,000 troops securing ports and airfields. Vietnam became one of the main staging areas for Japanese military operations in South East Asia for the next five years. During WW2 a movement for a national liberation of Vietnam from both the French and the Japanese developed in amongst Vietnamese exiles in southern China. -

By Dead Reckoning by Bill Mciver

index Abernathy, Susan McIver 23 , 45–47 36 , 42 Acheson, Dean Bao Dai 464 and Korea 248 , 249 Barrish, Paul 373 , 427 first to state domino theory 459 Bataan, Battling Bastards of 332 Acuff, Roy 181 Bataan Death March 333 Adams, M.D 444 Bataan Gang. See MacArthur, Douglas Adams, Will 31 Bataan Peninsula 329–333 Adkisson, Paul L. 436. See also USS Colahan bathythermograph 455 Alameda, California 268 , 312 , 315 , 317 , 320 , Battle of Coral Seas 296–297 335 , 336 , 338 , 339 , 345 , 346 , 349 , Battle off Samars 291 , 292 , 297–298 , 303 , 351 , 354 , 356 306–309 , 438 Alamogordo, New Mexico 63 , 64 Bedichek, Roy 220 Albano, Sam 371 , 372 , 373 , 414 , 425 , 426 , Bee County, Texas 12 , 17 , 19 427 Beeville, Texas 19 Albany, Texas 161 Belfast, Ireland 186 Albuquerque, New Mexico 228 , 229 Bengal, Oklahoma 94 Allred, Lue Jeff 32 , 44 , 200 Bidault, Georges 497 , 510 Alpine, Texas 67 Big Cypress Bayou, Texas 33 Amarillo, Texas 66 , 88 , 122 , 198 , 431 Big Spring, Texas 58 , 61 , 68 , 74 , 255 , 256 Ambrose, Stephen Bikini Atoll. See Operation Castle on Truman’s decision 466 , 467 Bilyeau, Paul 519 , 523 , 526 Anderson County, Texas 35 Blick, Robert 487 , 500 , 505 , 510 Anson County, North Carolina 21 Blytheville, Arkansas 112 Appling, Luke 224 Bockius, R.W. 272 , 273 , 288 , 289 , 290 Arapaho Reservation 50 commended by Halsey 273 Archer City, Texas 50 , 55 , 74 , 104 , 200 , 201 , during typhoon 288 , 289 , 290 259 on carrier work 272 Argyllshire, Scotland 45 Boerne, Texas 68 Arnold, Eddie 181 Bonamarte, Joseph 20 Arrington, Fred 164 Booth, Sarah 433 Ashworth, Barbara 110 , 219 , 220 , 433 , 434 Boudreau, Lou 175 Ashworth, Don 219 , 433 Bowers, Gary 361 , 375 , 386 , 427 Ashworth, Kenneth 219 , 220 Bowie, James 244 Ashworth, Mae 199 , 219 , 220 Bradley, Omar 252 Ashworth, R.B. -

RAN Ships Lost

CALL THE HANDS OCCASIONAL PAPER 6 Issue No. 6 March 2017 Royal Australian Navy Ships Honour Roll Given the 75th anniversary commemoration events taking place around Australia and overseas in 2017 to honour ships lost in the RAN’s darkest year, 1942 it is timely to reproduce the full list of Royal Australian Navy vessels lost since 1914. The table below was prepared by the Directorate of Strategic and Historical Studies in the RAN’s Sea Power Centre, Canberra lists 31 vessels lost along with a total of 1,736 lives. Vessel (* Denotes Date sunk Casualties Location Comments NAP/CPB ship taken up (Ships lost from trade. Only with ships appearing casualties on the Navy Lists highlighted) as commissioned vessels are included.) HMA Submarine 14-Sep-14 35 Vicinity of Disappeared following a patrol near AE1 Blanche Bay, Cape Gazelle, New Guinea. Thought New Guinea to have struck a coral reef near the mouth of Blanche Bay while submerged. HMA Submarine 30-Apr-15 0 Sea of Scuttled after action against Turkish AE2 Marmara, torpedo boat. All crew became POWs, Turkey four died in captivity. Wreck located in June 1998. HMAS Goorangai* 20-Nov-40 24 Port Phillip Collided with MV Duntroon. No Bay survivors. HMAS Waterhen 30-Jun-41 0 Off Sollum, Damaged by German aircraft 29 June Egypt 1941. Sank early the next morning. HMAS Sydney (II) 19-Nov-41 645 207 km from Sunk with all hands following action Steep Point against HSK Kormoran. Located 16- WA, Indian Mar-08. Ocean HMAS Parramatta 27-Nov-41 138 Approximately Sunk by German submarine. -

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles The Chinese Navy Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Saunders, EDITED BY Yung, Swaine, PhILLIP C. SAUNderS, ChrISToPher YUNG, and Yang MIChAeL Swaine, ANd ANdreW NIeN-dzU YANG CeNTer For The STUdY oF ChINeSe MilitarY AffairS INSTITUTe For NATIoNAL STrATeGIC STUdIeS NatioNAL deFeNSe UNIverSITY COVER 4 SPINE 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY COVER.indd 3 COVER 1 11/29/11 12:35 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 1 11/29/11 12:37 PM 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 2 11/29/11 12:37 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Edited by Phillip C. Saunders, Christopher D. Yung, Michael Swaine, and Andrew Nien-Dzu Yang Published by National Defense University Press for the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs Institute for National Strategic Studies Washington, D.C. 2011 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 3 11/29/11 12:37 PM Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Defense or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Chapter 5 was originally published as an article of the same title in Asian Security 5, no. 2 (2009), 144–169. Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. Used by permission. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Chinese Navy : expanding capabilities, evolving roles / edited by Phillip C. Saunders ... [et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

FROM CRADLE to GRAVE? the Place of the Aircraft

FROM CRADLE TO GRAVE? The Place of the Aircraft Carrier in Australia's post-war Defence Force Subthesis submitted for the degree of MASTER OF DEFENCE STUDIES at the University College The University of New South Wales Australian Defence Force Academy 1996 by ALLAN DU TOIT ACADEMY LIBRARy UNSW AT ADFA 437104 HMAS Melbourne, 1973. Trackers are parked to port and Skyhawks to starboard Declaration by Candidate I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of a university or other institute of higher learning, except where due acknowledgment is made in the text of the thesis. Allan du Toit Canberra, October 1996 Ill Abstract This subthesis sets out to study the place of the aircraft carrier in Australia's post-war defence force. Few changes in naval warfare have been as all embracing as the role played by the aircraft carrier, which is, without doubt, the most impressive, and at the same time the most controversial, manifestation of sea power. From 1948 until 1983 the aircraft carrier formed a significant component of the Australian Defence Force and the place of an aircraft carrier in defence strategy and the force structure seemed relatively secure. Although cost, especially in comparison to, and in competition with, other major defence projects, was probably the major issue in the demise of the aircraft carrier and an organic fixed-wing naval air capability in the Australian Defence Force, cost alone can obscure the ftindamental reordering of Australia's defence posture and strategic thinking, which significantly contributed to the decision not to replace HMAS Melbourne. -

D-Day the Invasion

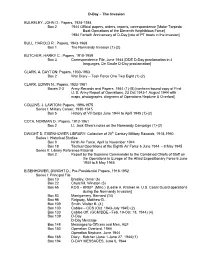

D-Day – The Invasion BULKELEY, JOHN D.: Papers, 1928-1984 Box 2 1944 Official papers, orders, reports, correspondence [Motor Torpedo Boat Operations of the Eleventh Amphibious Force] 1984 Fortieth Anniversary of D-Day [role of PT boats in the invasion] BULL, HAROLD R.: Papers, 1943-1968 Box 1 The Normandy Invasion (1)-(2) BUTCHER, HARRY C.: Papers, 1910-1959 Box 3 Correspondence File, June 1944 [DDE D-Day proclamation in 4 languages, De Gaulle D-Day proclamation] CLARK, A. DAYTON: Papers, 1930-1963 Box 2 War Diary – Task Force One Two Eight (1)-(2) CLARK, EDWIN N.: Papers, 1933-1981 Boxes 2-3 Army Records and Papers, 1944 (1)-(8) [contains bound copy of First U. S. Army Report of Operations, 23 Oct.1943-1 August 1944 with maps, photographs, diagrams of Operations Neptune & Overlord] COLLINS, J. LAWTON: Papers, 1896-1975 Series I: Military Career, 1930-1945 Box 5 History of VII Corps June 1944 to April 1945 (1)-(2) COTA, NORMAN D.: Papers, 1912-1961 Box 2 Lt. Jack Shea’s notes on the Normandy Campaign (1)-(2) DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY: Collection of 20th Century Military Records, 1918-1950 Series I: Historical Studies Box 9 Ninth Air Force, April to November 1944 Box 18 Tactical Operations of the Eighth Air Force 6 June 1944 – 8 May 1945 Series II: Library Reference Material Box 2 Report by the Supreme Commander to the Combined Chiefs of Staff on the Operations in Europe of the Allied Expeditionary Force 6 June 1944 to 8 May 1945 EISENHOWER, DWIGHT D.: Pre-Presidential Papers, 1916-1952 Series I: Principal File Box 13 Bradley, Omar (6) Box 22 Churchill, Winston (5) Box 65 KOS – KREP (Misc.) [Leslie A. -

Tasmanian Family History Society Inc

Tasmanian Family History Society Inc. PO Box 191 Launceston Tasmania 7250 State Secretary: [email protected] Journal Editors: [email protected] Home Page: http://www.tasfhs.org Patron: Dr Alison Alexander Fellows: Dr Neil Chick, David Harris and Denise McNeice Executive: President Anita Swan (03) 6326 5778 Vice President Maurice Appleyard (03) 6248 4229 Vice President Peter Cocker (03) 6435 4103 State Secretary Muriel Bissett (03) 6344 4034 State Treasurer Betty Bissett (03) 6344 4034 Committee: Judy Cocker Jim Rouse Kerrie Blyth Brian Hortle Leo Prior John Gillham Libby Gillham Helen Stuart Judith Whish-Wilson By-laws Officer Denise McNeice (03) 6228 3564 Assistant By-laws Officer Maurice Appleyard (03) 6248 4229 Webmaster Robert Tanner (03) 6231 0794 Journal Editors Anita Swan (03) 6326 5778 Betty Bissett (03) 6344 4034 LWFHA Coordinator Judith Whish-Wilson (03) 6394 8456 Members’ Interests Compiler John Gillham (03) 6239 6529 Membership Registrar Muriel Bissett (03) 6344 4034 Publications Coordinator Denise McNeice (03) 6228 3564 Public Officer Denise McNeice (03) 6228 3564 State Sales Officer Betty Bissett (03) 6344 4034 Branches of the Society Burnie: PO Box 748 Burnie Tasmania 7320 [email protected] Devonport: PO Box 587 Devonport Tasmania 7310 [email protected] Hobart: PO Box 326 Rosny Park Tasmania 7018 [email protected] Huon: PO Box 117 Huonville Tasmania 7109 [email protected] Launceston: PO Box 1290 Launceston Tasmania 7250 [email protected] Volume 28 Number 2 September 2007 ISSN 0159 0677 Contents Annual General Meeting Report ............................................................................ 74 President’s Annual Report ..................................................................................... 76 Lilian Watson Family History Award 2006 ............................................................. 77 Book Review—Winner of LWFH Award................................................................ -

Larson Newsletter Email Version Summer 2013

SUMMER 2013 Official Publication of the U.S.S. Everett F. Larson Association Newsletter Address: 83 Stonehedge Lane South, Guilford, CT 06437 WWW.USS-EVERETT-F-LARSON.COM PRESIDENTS CORNER The plans are set and Nashville is our next Port. I am really looking forward to our next reunion, I have been in contact with a couple new shipmates, both of them were on board in the 2012/2013 OFFICERS Executive Committee early sixty's. Both showed an interest in (includes Pres. & Vice Pres.) the reunion. Nick Nicholoff, President If you have never been to 18529 Maples Road Max Schwald Nashville, you are in for a real treat! Monroeville, IN 46773 155 Emerald St. The watering holes have live music, (260)623-6288 Sutherlin, OR 97479 good restaurants, shops with western [email protected] (541)459-2470 hats, boots and clothing. The hotel at [email protected] the Grand Ole Opry is a must see - John Clements, Vice President walk through gardens, waterfalls and 195 Elm Street Donald Erskine even a rotating bar!! It's really New Rochelle, NY 10805 115 Laguna Ln something, Nashville is just a fun place (914)235-1964 Boulder City, NV 89005 to be. Jone and I are looking forward to [email protected] (702)293-2024 seeing all of you and having another [email protected] outstanding reunion! Frank Wyzywany, Treasurer Liberty call 1600 12 Ashleigh Court Doug Rice - Nick Lansing, MI 48906 83 Stonehedge Lane (517)484-4762 Guilford, CT 06437 [email protected] (203)453-6137 From the Vice-President [email protected] Terry Weathers, Secretary 9964 Sniktaw Lane Gene Maresca The planning for Ft Jones, CA 96032-9745 Larson Historian the reunion has been completed., (530)468-2234 2406 East Rutgers Road and reservations are coming in [email protected] Indianapolis, IN 46227 everyday. -

The Hobson Incident

The Hobson Incident Late on Saturday night, April 26, 1952, U.S.S. Wasp was completing night maneuvers some 1,200 miles east of New York. She turned into the wind to recover her aircraft. The skipper of the USS Hobson, a destroyer-minesweeper, apparently became confused in the dark and made a few turns that ended with the Hobson cutting in front of Wasp. The Wasp cut the Hobson in two. From there, it rapidly got worse. The Hobson was hit aft of midship, and the entire ship sank in four minutes. Her captain and 174 other men were lost. In rolling over, Hobson’s keel sliced off an 80-ton section of Wasp’s bow, from keel to about waterline, the section being carried away, with interior deck levels, oil tanks, fittings, and gears. Those men from the Hobson who were fortunate enough to be thrown clear and rescued were covered with oil from Wasp’s broken tanks. Fortunately, there were no crew quarters located in Wasp’s bow, and Wasp, in fact, suffered no casualties in the affair. Wasp had been under orders to relieve the carrier Tarawa farther east. Her bulkheads holding against the open bow, she turned for repairs at New York. Proceeding at a ten-knot speed, often reduced to near zero when heavy going forced her to proceed stern-first, she almost lost her two anchor chains ($40,000 each). Wasp, drydock-free by May 19, then ammunitioned and service fitted, was back on sea duty in less than five weeks, a record for major ship repairs. -

Catalogue 212 OCTOBER 2018

1 Catalogue 212 OCTOBER 2018 Broinowski, L. (ed) Tasmania's War Record 1914-1918. J. Walch/The Govt of Tasmania, Hobart, 1921. 1st ed, small 4to in red cloth, titles gilt, inscr. In fep, comp. slip loose at front, plates, full rolls, enlistments by district, map, (p17} 2 Glossary of Terms (and conditions) INDEX Returns: books may be returned for refund within 7 days and only if not as described in the catalogue. NOTE: If you prefer to receive this catalogue via email, let us know on in- [email protected] CATEGORY PAGE My Bookroom is open each day by appointment – preferably in the afternoons. Give me a call. Aviation 3 Abbreviations: 8vo =octavo size or from 140mm to 240mm, ie normal size book, 4to = quarto approx 200mm x 300mm (or coffee table size); d/w = dust wrapper; Espionage 5 pp = pages; vg cond = (which I thought was self explanatory) very good condition. Other dealers use a variety including ‘fine’ which I would rather leave to coins etc. Illus = illustrations (as opposed to ‘plates’); ex lib = had an earlier life in library Military Biography 7 service (generally public) and is showing signs of wear (these books are generally 1st editions mores the pity but in this catalogue most have been restored); eps + end papers, front and rear, ex libris or ‘book plate’; indicates it came from a Military General 9 private collection and has a book plate stuck in the front end papers. Books such as these are generally in good condition and the book plate, if it has provenance, ie, is linked to someone important, may increase the value of the book, inscr = Napoleonic, Crimean & Victorian Eras 11 inscription, either someone’s name or a presentation inscription; fep = front end paper; the paper following the front cover and immediately preceding the half title page; biblio: bibliography of sources used in the compilation of a work (important Naval 12 to some military historians as it opens up many other leads). -

USS Stoddard Alumni Newsletter—January 2017 Page 2

Website: www.ussstoddard.org USS STODDARD Date: January 15th, 2017 ALUMNI NEWSLETTER USS STODDARD DD566 WWII * Korea * Vietnam 29th Reunion—New Orleans, Louisiana Crowne Plaza 2829 Williams Blvd. September 20th – September 23rd - 2017 Kenner, LA 70062 Hosts: John & Carlene Rauh Email: [email protected] Room Rate: $115.00 Two Days Before & After Reunion We welcome everyone to a place where centuries old architec- Breakfast ture is the backdrop for a culture to arouse your spirit. The city Restaurant of New Orleans is a magical place to explore. Enjoy the history, Free Parking food, and historical sites. Free Internet Airport Shuttle The National WWII Museum is considered one of the top museums Reservation the nation. It tells the story of the American Experience in the war information— that changed the world. The movie see page 8 “Beyond All Boundaries” is a 4D journey through the war narrated by Tom Hanks. Inside this issue: The French Quarter, also known as the Vieuz Carre, is the oldest 2017 New Orleans 2 neighborhood in the city of New Or- leans founded in 1718. Most of the Portland Reunion 3 & 4 historic buildings were constructed Hobson Accident 5 & 6 in the late Tom Davis Poem 7 18th cen- Annual Meeting 8 tury dur- ing the Hotel Info 8 Spanish rule or built during the first Chaplain’s Report 9 half of the 19th century, after U.S. an- Directory Update 9 nexation. The district has been desig- Ship’s Store 10 nated as a National Historic Landmark. USS Stoddard Alumni Newsletter—January 2017 Page 2 NATCHEZ Jazz Dinner Cruise. -

THE JERSEYMAN 6 Years - Nr

1st Quarter 2008 "Rest well, yet sleep lightly and hear the call, if again sounded, to provide firepower for freedom…” THE JERSEYMAN 6 Years - Nr. 57 Rear Admiral J. Edward Snyder, Jr., USN (Retired) (1924 - 2007) 2 The Jerseyman Rear Admiral J. Edward Snyder, Jr., USN (Ret.) (1924 - 2007) Born in Grand Forks, North Dakota on 23 October 1924, Admiral Snyder entered the US Naval Academy on 23 July 1941 and graduated as an Ensign on 7 June 1944. After attending a course of instruction at NAS Jacksonville from July 1944 to October 1944, he was ordered to USS Pennsylvania (BB-38), and served as Signal Officer until October 1946. Cruiser assignments followed in USS Toledo (CA-133), and USS Macon (CA-132). From January 1949 to February 1950, Snyder was assigned instruction at the Armed Forces Special Weapon Project, Field Activities at Sandia Base, New Mexico, and at the Navy Special Weapons unit #1233, Special Weapons Project, Los Alamos, New Mexico. He was then assigned as a Staff Member, Armed Forces Special Weapons Project at the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory in Albuquerqe, New Mexico. From July 1951 to August 1952, Lieutenant Snyder was assigned as First Lieuten- ant/Gunnery Officer in USS Holder (DDE-819). From August 1952 to June 1953 he attended Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California, and it was followed by instruction at the Naval Administration Unit, Massachussetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Mass., from June 1953 to June 1955. Fleet Sonar school, Key West, Florida fol- lowed from June 1955 to August 1955. Lieutenant Commander Snyder was assigned from August 1955 to January 1956 as Executive Officer and Navigator in USS Everett F.