Wartime Film Stardom and Global Leadership

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9781474451062 - Chapter 1.Pdf

Produced by Irving Thalberg 66311_Salzberg.indd311_Salzberg.indd i 221/04/201/04/20 66:34:34 PPMM 66311_Salzberg.indd311_Salzberg.indd iiii 221/04/201/04/20 66:34:34 PPMM Produced by Irving Thalberg Theory of Studio-Era Filmmaking Ana Salzberg 66311_Salzberg.indd311_Salzberg.indd iiiiii 221/04/201/04/20 66:34:34 PPMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © Ana Salzberg, 2020 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/13 Monotype Ehrhardt by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 5104 8 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 5106 2 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 5107 9 (epub) The right of Ana Salzberg to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 66311_Salzberg.indd311_Salzberg.indd iivv 221/04/201/04/20 66:34:34 PPMM Contents Acknowledgments vi 1 Opening Credits 1 2 Oblique Casting and Early MGM 25 3 One Great Scene: Thalberg’s Silent Spectacles 48 4 Entertainment Value and Sound Cinema -

Breaking Into the Movies Online

1URQw [Download free pdf] Breaking into the movies Online [1URQw.ebook] Breaking into the movies Pdf Free John Emerson, Anita Loos *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #14132949 in Books 2012-08-31 2012-08-31Original language:English 10.00 x .33 x 7.50l, #File Name: B00AODF8MS146 pages | File size: 46.Mb John Emerson, Anita Loos : Breaking into the movies before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Breaking into the movies: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Also written by Anita LoosBy Susan OliverI read this book as a historical document as it was published in 1921. I read it for free on archive.org =[...]But more important, I read this book because it was co-written by a woman - Anita Loos. The summary does not mention her name.Anita Loos wrote "Gentlemen Prefer Blondes" and also wrote the following:Fiction Gentlemen Prefer Blondes: The Intimate Diary of A Professional Lady. NY:Boni Liveright, 1926 But Gentlemen Marry Brunettes.NY:Boni Liveright, 1928 A Mouse is Born. NY:Doubleday Company, 1951 No Mother to Guide Her. NY:McGraw Hill, 1961 Fate Keeps On Happening: Adventures Of Lorelei Lee And Other Writings. NY:Dodd, Mead Company, 1984 Nonfiction w/ John Emerson How to Write Photoplays NY:James A McCann, 1920 w/ John Emerson. Breaking Into the Movies. NY:James A McCann, 1921 "This Brunette Prefers Work", Woman's Home Companion, 83 (March 1956) A Girl Like I. NY:Viking Press, 1966 w/ Helen Hayes. -

Movie Mirror Book

WHO’S WHO ON THE SCREEN Edited by C h a r l e s D o n a l d F o x AND M i l t o n L. S i l v e r Published by ROSS PUBLISHING CO., I n c . NEW YORK CITY t y v 3. 67 5 5 . ? i S.06 COPYRIGHT 1920 by ROSS PUBLISHING CO., Inc New York A ll rights reserved | o fit & Vi HA -■ y.t* 2iOi5^ aiblsa TO e host of motion picture “fans” the world ovi a prince among whom is Oswald Swinney Low sley, M. D. this volume is dedicated with high appreciation of their support of the world’s most popular amusement INTRODUCTION N compiling and editing this volume the editors did so feeling that their work would answer a popular demand. I Interest in biographies of stars of the screen has al ways been at high pitch, so, in offering these concise his tories the thought aimed at by the editors was not literary achievement, but only a desire to present to the Motion Picture Enthusiast a short but interesting resume of the careers of the screen’s most popular players, rather than a detailed story. It is the editors’ earnest hope that this volume, which is a forerunner of a series of motion picture publications, meets with the approval of the Motion Picture “ Fan” to whom it is dedicated. THE EDITORS “ The Maples” Greenwich, Conn., April, 1920. whole world is scene of PARAMOUNT ! PICTURES W ho's Who on the Screcti THE WHOLE WORLD IS SCENE OF PARAMOUNT PICTURES With motion picture productions becoming more masterful each year, with such superb productions as “The Copperhead, “Male and Female, Ireasure Island” and “ On With the Dance” being offered for screen presentation, the public is awakening to a desire to know more of where these and many other of the I ara- mount Pictures are made. -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158. -

Thrift, Sacrifice, and the World War II Bond Campaigns

Saving for Democracy University Press Scholarship Online Oxford Scholarship Online Thrift and Thriving in America: Capitalism and Moral Order from the Puritans to the Present Joshua Yates and James Davison Hunter Print publication date: 2011 Print ISBN-13: 9780199769063 Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: May 2012 DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199769063.001.0001 Saving for Democracy Thrift, Sacrifice, and the World War II Bond Campaigns Kiku Adatto DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199769063.003.0016 Abstract and Keywords This chapter recounts the war bond campaign of the Second World War, illustrating a notion of thrift fully embedded in a social attempt to serve the greater good. Saving money was equated directly with service to the nation and was pitched as a duty of sacrifice to support the war effort. One of the central characteristics of this campaign was that it enabled everyone down to newspaper boys to participate in a society-wide thrift movement. As such, the World War II war bond effort put thrift in the service of democracy, both in the sense that it directly supported the war being fought for democratic ideals and in the sense that it allowed the participation of all sectors in the American war effort. This national ethic of collective thrift for the greater good largely died in the prosperity that followed World War II, and it has not been restored even during subsequent wars in the latter part of the 20th century. Keywords: Second World War, war bonds, thrift, democracy, war effort Page 1 of 56 PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). -

George Eastman Museum Annual Report 2018

George Eastman Museum Annual Report 2018 Contents Exhibitions 2 Traveling Exhibitions 3 Film Series at the Dryden Theatre 4 Programs & Events 5 Online 7 Education 8 The L. Jeffrey Selznick School of Film Preservation 8 Photographic Preservation & Collections Management 8 Photography Workshops 9 Loans 10 Objects Loaned For Exhibitions 10 Film Screenings 15 Acquisitions 17 Gifts to the Collections 17 Photography 17 Moving Image 30 Technology 32 George Eastman Legacy 34 Richard and Ronay Menschel Library 48 Purchases for the Collections 48 Photography 48 Moving Image 49 Technology 49 George Eastman Legacy 49 Richard and Ronay Menschel Library 49 Conservation & Preservation 50 Conservation 50 Photography 50 Technology 52 George Eastman Legacy 52 Richard and Ronay Menschel Library 52 Preservation 53 Moving Image 53 Financial 54 Treasurer’s Report 54 Fundraising 56 Members 56 Corporate Members 58 Annual Campaign 59 Designated Giving 59 Planned Giving 61 Trustees, Advisors & Staff 62 Board of Trustees 62 George Eastman Museum Staff 63 George Eastman Museum, 900 East Avenue, Rochester, NY 14607 Exhibitions Exhibitions on view in the museum’s galleries during 2018. MAIN GALLERIES HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY GALLERY Stories of Indian Cinema: A History of Photography Abandoned and Rescued Curated by Jamie M. Allen, associate curator, Department of Photography, and Todd Gustavson, exhibitions, Moving Image Department curator, Technology Collection NovemberCurated by 11,Jurij 2017–May Meden, curator 13, 2018 of film October 14, 2017–April 22, 2018 Nandita -

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding Aid Prepared by Lisa Deboer, Lisa Castrogiovanni

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding aid prepared by Lisa DeBoer, Lisa Castrogiovanni and Lisa Studier and revised by Diana Bowers-Smith. This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit September 04, 2019 Brooklyn Public Library - Brooklyn Collection , 2006; revised 2008 and 2018. 10 Grand Army Plaza Brooklyn, NY, 11238 718.230.2762 [email protected] Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 7 Historical Note...............................................................................................................................................8 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 8 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................9 Collection Highlights.....................................................................................................................................9 Administrative Information .......................................................................................................................10 Related Materials ..................................................................................................................................... -

Town of Cohasset

COHASSET TOWN REPORT 1919 One Hundred and Fiftieth Annual Report of the BOARD OF SELECTMEN OF THE FINANCIAL AFFAIRS OF THE TOWN OF COHASSET AND THE REPORT OF OTHER TOWN OFFICERS FOR THE YEAR ENDING DECEMBER 31 1919 THE BOUNDBROOK PRESS 1920 TOWN OFFICERS, 1919-1920 Elected by ballot Town Clerk HARRY F. TILDEN . Term expires March, 1920 Selectmen, Assessors and Overseers of Poor HARRY E. MAPEvS . Term expires March, 1922 HERBERT L. BROWN . Term expires March, 1921 DARIUS W. GILBERT . Term expires March, 1923 Treasurer and Collector of Taxes NEWCOMB B. TOWER Highway Surveyor GEORGE JASON Constables FRANK J. ANTOINE SIDNEY L. BEAL THOMAS L. BATES JOHN T. KEATING LOUIS J. MORRIS Finance Committee CHARLES W. GAMMONS Term expires March, 1921 CORNELIUS KEEFE . Term expires March, 1921 EDWARD F. WILLCUTT Term expires March, 1921 ^ ..._ ^^_„_i. EDWIN W. BATES Term expires March, J920 WILLIAM H. McGAW . Term expires March 1923 JOHN A. LAWRENCE . Term expires March, 1922 EDWIN T. OTIS Term expires March, 1922 Tree Warden GEORGE YOUNG 3 School Committee GEORGE JAvSON, JR.* . Term expires March, 1921 WALTER SHUEBRUK . Term expires March, 1921 THOMAS A. STEVENS . Term expires March, 1922 DEAN K. JAMES Term expires March, 1922 ANSELM L. BEAL Term expires March, 1920 REV. FRED V. STANLEY Term expires March, 1920 MANUEL A. GRASSIEt Board of Health IRVING F. SYLVESTER . Term expires March, 1920 FRED L. REED* . Term expires March, 1921 DR. FREDERICK HINCHLIFFE Term expires March, 1922 EDWARD L. HIGGINSt Trustees of Public Library EDITH M. BATES Termi expires March, 1920 MARTHA P. HOWE . Term expires March, 1920 OLIVER H. -

Report to the U. S. Congress for the Year Ending December 31, 2003

Report to the U.S.Congress for the Year Ending December 31,2003 Created by the U.S. Congress to Preserve America’s Film Heritage Created by the U.S. Congress to Preserve America’s Film Heritage April 30, 2004 Dr. James H. Billington The Librarian of Congress Washington, D.C. 20540-1000 Dear Dr. Billington: In accordance with Public Law 104-285 (Title II), The National Film Preservation Foundation Act of 1996, I submit to the U.S. Congress the 2003 Report of the National Film Preservation Foundation. It gives me great pleasure to review our accomplishments in carrying out this Congressional mandate. Since commencing service to the archival community in 1997, we have helped save 630 historically and culturally significant films from 98 institutions across 34 states and the District of Columbia. We have produced The Film Preservation Guide: The Basics for Archives, Libraries, and Museums, the first such publication designed specifically for regional preservationists, and have pioneered in pre- senting archival films on widely distributed DVDs and on American television. Unseen for decades, motion pictures preserved through our programs are now extensively used in study and exhibition. There is still much to do. This year Congress will consider the reauthorization of our federal grant programs. Increased funding will enable us to expand service to the nation’s archives, libraries, and museums and do more toward saving America’s film heritage for future generations. The film preser- vation community appreciates your efforts to make the case for increased federal investment. We are deeply grateful for your leadership. Space does not permit my acknowledging all those supporting our efforts in 2003, but I would like to single out several organizations that have played an especially significant role: the National Endowment for the Humanities, The Andrew W. -

GSC Films: S-Z

GSC Films: S-Z Saboteur 1942 Alfred Hitchcock 3.0 Robert Cummings, Patricia Lane as not so charismatic love interest, Otto Kruger as rather dull villain (although something of prefigure of James Mason’s very suave villain in ‘NNW’), Norman Lloyd who makes impression as rather melancholy saboteur, especially when he is hanging by his sleeve in Statue of Liberty sequence. One of lesser Hitchcock products, done on loan out from Selznick for Universal. Suffers from lackluster cast (Cummings does not have acting weight to make us care for his character or to make us believe that he is going to all that trouble to find the real saboteur), and an often inconsistent story line that provides opportunity for interesting set pieces – the circus freaks, the high society fund-raising dance; and of course the final famous Statue of Liberty sequence (vertigo impression with the two characters perched high on the finger of the statue, the suspense generated by the slow tearing of the sleeve seam, and the scary fall when the sleeve tears off – Lloyd rotating slowly and screaming as he recedes from Cummings’ view). Many scenes are obviously done on the cheap – anything with the trucks, the home of Kruger, riding a taxi through New York. Some of the scenes are very flat – the kindly blind hermit (riff on the hermit in ‘Frankenstein?’), Kruger’s affection for his grandchild around the swimming pool in his Highway 395 ranch home, the meeting with the bad guys in the Soda City scene next to Hoover Dam. The encounter with the circus freaks (Siamese twins who don’t get along, the bearded lady whose beard is in curlers, the militaristic midget who wants to turn the couple in, etc.) is amusing and piquant (perhaps the scene was written by Dorothy Parker?), but it doesn’t seem to relate to anything. -

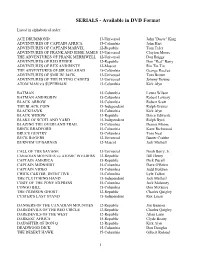

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format Listed in alphabetical order: ACE DRUMMOND 13-Universal John "Dusty" King ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN AFRICA 15-Columbia John Hart ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN MARVEL 12-Republic Tom Tyler ADVENTURES OF FRANK AND JESSE JAMES 13-Universal Clayton Moore THE ADVENTURES OF FRANK MERRIWELL 12-Universal Don Briggs ADVENTURES OF RED RYDER 12-Republic Don "Red" Barry ADVENTURES OF REX AND RINTY 12-Mascot Rin Tin Tin THE ADVENTURES OF SIR GALAHAD 15-Columbia George Reeves ADVENTURES OF SMILIN' JACK 13-Universal Tom Brown ADVENTURES OF THE FLYING CADETS 13-Universal Johnny Downs ATOM MAN v/s SUPERMAN 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BATMAN 15-Columbia Lewis Wilson BATMAN AND ROBIN 15-Columbia Robert Lowery BLACK ARROW 15-Columbia Robert Scott THE BLACK COIN 15-Independent Ralph Graves BLACKHAWK 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BLACK WIDOW 13-Republic Bruce Edwards BLAKE OF SCOTLAND YARD 15-Independent Ralph Byrd BLAZING THE OVERLAND TRAIL 15-Columbia Dennis Moore BRICK BRADFORD 15-Columbia Kane Richmond BRUCE GENTRY 15-Columbia Tom Neal BUCK ROGERS 12-Universal Buster Crabbe BURN'EM UP BARNES 12-Mascot Jack Mulhall CALL OF THE SAVAGE 13-Universal Noah Berry, Jr. CANADIAN MOUNTIES v/s ATOMIC INVADERS 12-Republic Bill Henry CAPTAIN AMERICA 15-Republic Dick Pucell CAPTAIN MIDNIGHT 15-Columbia Dave O'Brien CAPTAIN VIDEO 15-Columbia Judd Holdren CHICK CARTER, DETECTIVE 15-Columbia Lyle Talbot THE CLUTCHING HAND 15-Independent Jack Mulhall CODY OF THE PONY EXPRESS 15-Columbia Jock Mahoney CONGO BILL 15-Columbia Don McGuire THE CRIMSON GHOST 12-Republic -

A Companion to Literature, Film, and Adaptation Blackwell Companions to Literature and Culture

A Companion to Literature, Film, and Adaptation Blackwell Companions to Literature and Culture This series offers comprehensive, newly written surveys of key periods and movements and certain major authors, in English literary culture and history. Extensive volumes provide new perspectives and positions on contexts and on canonical and post-canonical texts, orientating the beginning student in new fields of study and providing the experienced undergraduate and new graduate with current and new directions, as pioneered and developed by leading scholars in the field. Published Recently 62. A Companion to T. S. Eliot Edited by David E. Chinitz 63. A Companion to Samuel Beckett Edited by S. E. Gontarski 64. A Companion to Twentieth-Century United States Fiction Edited by David Seed 65. A Companion to Tudor Literature Edited by Kent Cartwright 66. A Companion to Crime Fiction Edited by Charles Rzepka and Lee Horsley 67. A Companion to Medieval Poetry Edited by Corinne Saunders 68. A New Companion to English Renaissance Literature and Culture Edited by Michael Hattaway 69. A Companion to the American Short Story Edited by Alfred Bendixen and James Nagel 70. A Companion to American Literature and Culture Edited by Paul Lauter 71. A Companion to African American Literature Edited by Gene Jarrett 72. A Companion to Irish Literature Edited by Julia M. Wright 73. A Companion to Romantic Poetry Edited by Charles Mahoney 74. A Companion to the Literature and Culture of the American West Edited by Nicolas S. Witschi 75. A Companion to Sensation Fiction Edited by Pamela K. Gilbert 76. A Companion to Comparative Literature Edited by Ali Behdad and Dominic Thomas 77.