Redefining Public Art in Toronto — Vision and Recommendations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae

Cole Swanson | Curriculum Vitae Education University of Toronto Masters of Art, Art History 2013 University of Guelph Bachelor of Arts, Honours: Studio Art 2004 Solo & Dual Exhibitions Spadina House Museum, Toronto Research Project and Solo Exhibition – TBA (forthcoming) 2020 Hamilton Artist Inc, Cannon Gallery, Hamilton Devil’s Colony (forthcoming) 2019 Rajasthan Lalit Kala Academy, Jaipur The Furrow, The Froth 2018 The Open Space Society, Jaipur िमटटी िसटी | Mitti City 2018 Unilever Factory & Design Exchange, Toronto Muzzle and Hoof, Horn and Bone 2017 Expo for Design, Innovation, and Technology Casa Na Ilha, Ilhabela, Brazil Lecanora Muralis 2017 Art Gallery of Guelph, Guelph Out of the Strong, Something Sweet 2016 Jawahar Kala Kendra, Jaipur, India Red Earth 2014 Museum of Northern History, Kirkland Lake Monuments & Melodramas 2012 Le Gallery, Toronto Next Exit (with Jennie Suddick) 2011 Ministry of Casual Living, Victoria, BC Mile Zero (with Jennie Suddick) 2011 Jawahar Kala Kendra, Jaipur, India of a feather 2007 Zero Four Art Space, Chung Li, Taiwan of a feather 2006 The Canadian Trade Office, Taipei, Taiwan of a feather 2006 Stirred a Bird Gallery, Guelph everybody in Flamingo 2005 Zavitz Hall Gallery, Guelph Shauchaalaya/Latrine 2003 Selected Group Exhibitions 2020 The Reach Glimmers of the Radiant Real (Forthcoming) Abbottsford, BC 2019 McIntosh Gallery, University of Western Ontario Glimmers of the Radiant Real (Forthcoming) London Gladstone Hotel Come Up to My Room, Terraflora (Solo) Toronto 2018 Paul Petro Contemporary Art -

Financial Reporting and Is Ultimately Responsible for Reviewing and Approving the Financial Statements

Treasury Board Secretariat ANNUAL REPORT OF ONTARIO Financial Statements of Government Organizations VOLUME 2B | 2015-2016 7$%/( 2)&217(176 9ROXPH% 3DJH *HQHUDO 5HVSRQVLEOH0LQLVWU\IRU*RYHUQPHQW$JHQFLHV LL $*XLGHWRWKHAnnual Report .. LY ),1$1&,$/ 67$7(0(176 6HFWLRQ ņ*RYHUQPHQW 2UJDQL]DWLRQV± &RQW¶G 1LDJDUD3DUNV&RPPLVVLRQ 0DUFK 1RUWKHUQ2QWDULR+HULWDJH)XQG&RUSRUDWLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR$JHQF\IRU+HDOWK 3URWHFWLRQDQG 3URPRWLRQ 3XEOLF+HDOWK2QWDULR 0DUFK 2QWDULR&DSLWDO*URZWK&RUSRUDWLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR&OHDQ :DWHU$JHQF\ 'HFHPEHU 2QWDULR(GXFDWLRQDO&RPPXQLFDWLRQV$XWKRULW\ 79 2QWDULR 0DUFK 2QWDULR(OHFWULFLW\)LQDQFLDO&RUSRUDWLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR(QHUJ\%RDUG 0DUFK 2QWDULR)LQDQFLQJ$XWKRULW\ 0DUFK 2QWDULR)UHQFK/DQJXDJH(GXFDWLRQDO&RPPXQLFDWLRQV$XWKRULW\ 0DUFK 2QWDULR,PPLJUDQW,QYHVWRU&RUSRUDWLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR,QIUDVWUXFWXUH DQG/DQGV&RUSRUDWLRQ ,QIUDVWUXFWXUH 2QWDULR 0DUFK 2QWDULR0RUWJDJH DQG+RXVLQJ&RUSRUDWLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR1RUWKODQG7UDQVSRUWDWLRQ&RPPLVVLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR3ODFH&RUSRUDWLRQ 'HFHPEHU 2QWDULR5DFLQJ&RPPLVVLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR6HFXULWLHV&RPPLVVLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR7RXULVP0DUNHWLQJ3DUWQHUVKLS&RUSRUDWLRQ 0DUFK 2QWDULR7ULOOLXP)RXQGDWLRQ 0DUFK 2UQJH 0DUFK 2WWDZD&RQYHQWLRQ&HQWUH &RUSRUDWLRQ 0DUFK 3URYLQFH RI2QWDULR&RXQFLOIRUWKH$UWV 2QWDULR$UWV&RXQFLO 0DUFK 7KH 5R\DO2QWDULR0XVHXP 0DUFK 7RURQWR 2UJDQL]LQJ&RPPLWWHHIRUWKH 3DQ $PHULFDQ DQG3DUDSDQ$PHULFDQ*DPHV 7RURQWR 0DUFK 7RURQWR :DWHUIURQW5HYLWDOL]DWLRQ&RUSRUDWLRQ :DWHUIURQW7RURQWR 0DUFK L ANNUAL REPORT 5(63216,%/(0,1,675<)25*29(510(17%86,1(66(17(535,6(6 25*$1,=$7,216758676 0,6&(//$1(286),1$1&,$/67$7(0(176 -

OAC Grant Application • 3Rd Edition

OAC Grant Application • 3 rd Edition Tips and must-dos for preparing an application to the Ontario Arts Council Ontario Arts Council About the Ontario Arts Council 151 Bloor Street West, 5th Floor Toronto, Ontario, M5S 1T6 The Ontario Arts Council (OAC) is a publicly funded, 416-961-1660 independent agency of the government of Ontario. Toll-free in Ontario: 1-800-387-0058 We have been supporting Ontario-based artists and [email protected] / www.arts.on.ca not-for-profit arts organizations since 1963. OAC’s mission is to promote and assist the development of the arts for the benefit and enjoyment of all Ontarians. Over the years, OAC has fostered stability and growth in Ontario’s arts communities. The Ontario Arts Council welcomes all forms of artistic expression. We are committed to funding art from all the people and regions of Ontario. We offer full service in English and French. All OAC programs are open to Aboriginal artists or arts organizations and artists or arts organizations from diverse cultural communities. OAC Grant Application Survival Guide 4 Introduction ..................................................................................... 3 Grants for Individual Artists and Groups .................................. 3 What Kind of Projects Can You Do with an OAC Grant? ............. 4 Briefly, the process… Who Can Apply? ............................................................................. 5 • Eligibility—make sure you are eligible to apply • Find the right grant program • Read—make sure you understand the application and guidelines • Gather information and brainstorm Which Program Do I Choose? ..................................................... 7 OAC Contacts .................................................................................................7 • Writing—start with a draft What’s in an Application? ......................................................................... 8 • Ask for feedback on your draft How Do I Apply? ......................................................................................... -

Ontario Government Acronyms

ACSP COSINE Archaeology Customer Service Project Coordinated Survey Information Network Exchange ADP (MNR database) Assistive Devices Program EBR AGO Environmental Bill of Rights Art Gallery of Ontario EODC ARF Eastern Ontario Development Corporation Addiction Research Foundation EQAO ATOP Educational Quality and Accountability Office Access to Opportunities Program ERC BUC Education Relations Commission Biosolids Utilization Committee (Pronounced: BUCK, as in BUCboard) FCOISA Foreign Cultural Objects Immunity from Seizure CAATs Act Colleges of Applied Arts and Technology FIPPA Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy CAMH Act Centre for Addiction and Mental Health FSCO CCAC Financial Services Commission of Ontario Community Care Access Centres GAINS CISO Guaranteed Annual Income System Criminal Intelligence Service Ontario GO CORPAY Government of Ontario Corporate Payroll. Maintained by (as in Go Transit or GO-NET) Human Resources System Branch GO-ITS LCBO Government of Ontario Information and Liquor Control Board of Ontario Technology Standards LEAP GTS Learning, Earning and Parenting (program) Government Translation Service LLBO HOP Liquor Licence Board of Ontario Home Oxygen Program (under ADP) LRIF Locked-in Retirement Income Fund IDO Investment and Development Office MAG Ministry of the Attorney General IESO Independent Electricity System Operator MBS Management Board Secretariat ILC Independent Learning Centre MCI Ministry of Citizenship and Immigration IMPAC Interministerial Provincial Advisory MCL Committee Ministry of -

MANGAARD C.V 2019 (6Pg)

ANNETTE MANGAARD Film/Video/Installation/Photography Born: Lille Værløse, Denmark. Canadian Citizen Education: MFA, Gold Medal Award, OCAD University 2017 BIO Annette Mangaard is a Danish born Canadian media artist and filmmaker who has recently completed her Masters in Interdisciplinary Art, Media and Design. Her installation work has been shown around the world including: the Armoury Gallery, Olympic Site in Sydney Australia; Pearson International Airport, Toronto; South-on Sea, Liverpool and Manchester, UK; Universidad Nacional de Río Negro, Patagonia, Argentina; and Whitefish Lake, First Nations, Ontario. Mangaard has completed more then 16 films in more than a decade as an independent filmmaker. Her feature length experimental documentary on photographer Suzy Lake and the history of feminism screened as part of the INTRODUCING SUZY LAKE exhibition October 2014 through March 2015 at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Mangaard was nominated for a Gemini for Best Director of a Documentary for her one hour documentary, GENERAL IDEA: ART, AIDS, AND THE FIN DE SIECLE about the celebrated Canadian artists collective which premiered at Hot Doc’s in Toronto then went on to garner accolades around the world. Mangaard’s one hour documentary KINNGAIT: RIDING LIGHT INTO THE WORLD, about the changing face of the Inuit artists of Cape Dorset premiered at the Art Gallery of Ontario and was invited to Australia for a special screening celebrating Canada Day with the Canadian High Commission. Mangaard’s body of work was presented as a retrospective at the Palais de Glace, Buenos Aires, Argentina in 2009 and at the PAFID, Patagonia, Argentina in 2013. In 1990 Mangaard was invited to present solo screenings of her films at the Pacific Cinematheque in Vancouver, Canada and in 1991 at the Kino Arsenal Cinematheque in Berlin, West Germany. -

White Paper on Francophone Arts and Culture in Ontario Arts and Culture

FRANCOPHONE ARTS AND CULTURE IN ONTARIO White Paper JUNE 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY 05 BACKGROUND 06 STATE OF THE FIELD 09 STRATEGIC ISSUES AND PRIORITY 16 RECOMMANDATIONS CONCLUSION 35 ANNEXE 1: RECOMMANDATIONS 36 AND COURSES OF ACTION ARTS AND CULTURE SUMMARY Ontario’s Francophone arts and culture sector includes a significant number of artists and arts and culture organizations, working throughout the province. These stakeholders are active in a wide range of artistic disciplines, directly contribute to the province’s cultural development, allow Ontarians to take part in fulfilling artistic and cultural experiences, and work on the frontlines to ensure the vitality of Ontario’s Francophone communities. This network has considerably diversified and specialized itself over the years, so much so that it now makes up one of the most elaborate cultural ecosystems in all of French Canada. However, public funding supporting this sector has been stagnant for years, and the province’s cultural strategy barely takes Francophones into account. While certain artists and arts organizations have become ambassadors for Ontario throughout the country and the world, many others continue to work in the shadows under appalling conditions. Cultural development, especially, is currently the responsibility of no specific department or agency of the provincial government. This means that organizations and actors that increase the quality of life and contribute directly to the local economy have difficulty securing recognition or significant support from the province. This White Paper, drawn from ten regional consultations held throughout the province in the fall of 2016, examines the current state of Francophone arts and culture in Ontario, and identifies five key issues. -

Alexa Hatanaka CV Jun 15 2020

ALEXA HATANAKA Collectives: PA System, Embassy of Imagination (EOI) EDUCATION 2012 Printmaking with distinction, OCAD University, Toronto, ON, Canada: BFA 2011 Nanjing Arts Institute, China, OCADU exchange program, traditional Chinese Printmaking SOLO EXHIBITIONS AND COLLABORATIONS 2021 Solo Show (Title TBD), AXENE07, Gatineau, QC, Canada (PA System) 2020 Arctic: Culture and Climate, The British Museum, London, England, UK (PA System + EOI) 2019 Do you want to take the short-cut or the long-cut?, Open Studio Gallery, Toronto, ON, Canada (PA System) 2019 PA System, General Hardware, Toronto, ON, Canada (PA System) 2018 wind wind, The Trace Gallery, Zurich, Switzerland (PA System) 2014 Larding and Barding, The Trace Gallery, Zurich, Switzerland (PA System) 2012 Cultural Persistence, DDR Projects, Long Beach, CA, USA 2012 Evoke’s Pancake House, Montana Gallery, Barcelona, Spain (PA System) 2011 Donnacona, La Place Forte, Paris, France (PA System) 2011 Think Tent, Le Labo, Toronto, ON, Canada 2010 Choose Your Own Adventure, Articulate Baboon, Cairo, Egypt (PA System) 2010 It’ll Come Out in the Wash, 52, Toronto, ON, Canada GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2019 Sinaaqpagiaqtuut/The Long-Cut, Toronto Biennial of Art & The Bentway, Toronto, ON, Canada (PA System + EOI) 2019 Nature As Communities, Dalhousie Art Gallery, Halifax, NS, Canada (PA System + EOI) 2018 uvanga and imagine if, Legislative Assembly of Nunavut Gallery, Iqaluit, NU, Canada (EOI) 2017 Every. Now. Then: Reframing Nationhood, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, ON, Canada (PA System + EOI) 2017 -

Concordia Campus Sustainability Assessment

CONCORDIA CAMPUS SUSTAINABILITY ASSESSMENT CONTENTS FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT .................................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................4 CLUSTER 1 – OPERATIONS AND INFRASTRUCTURE ......................................................................7 Transportation ........................................................................................................................7 Buildings................................................................................................................................12 Energy & Climate ...................................................................................................................15 Landscape .............................................................................................................................20 Purchasing.............................................................................................................................24 Waste ....................................................................................................................................27 Water ....................................................................................................................................33 CLUSTER 2 – AWARENESS -

Creating Vibrant Cities Des Villes Passionnément Vibrantes

LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE IN CANADA LANDSCAPES PAYSAGES L’ARCHITECTURE DE PAYSAGE AU CANADA $5.95 Spring/Printemps 2006 Vol. 8/No. 2 Creating Vibrant Cities Des villes passionnément vibrantes The Canadian Society of Landscape Architects L’Association des architectes paysagistes du Canada www.csla.ca ADDITIONAL FENCE SYSTEMS FROM AMERISTAR DISTRIBUTORS THROUGHOUT CANAD A - CALL 1-888-333-3422 Ameristar Fence Products 1555 N. Mingo Rd. Tulsa, Ok 74116 www.MontageFence.com LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE IN CANADA LANDSCAPES PAYSAGES 10 L’ARCHITECTURE DE PAYSAGE AU CANADA Spring/Printemps 2006 Vol. 8/No. 2 Editorial/Éditorial 7 Passionate Advocates for Beauty/La beauté passionnément by/par Doug Carlyle, Guest Editor/Rédacteur invité Features/Articles-vedettes 10 Vancouver’s “Living First” Strategy/« Vivre d’abord » : le centre-ville de Vancouver by/par Larry Beasley 19 25 The Bridges: A Calgary Neighbourhood Comes Alive/Les ponts : un quartier calgarien à ses premiers cris by/par Jeremy Sturgess 32 An Education in Urban Design: Calgary’s Urban Lab/Une leçon en aménagement : le laboratoire urbain de Calgary by/par Bev Sandalack 38 Le développement durable de la ville de Montréal/Montréal: A Sustainable Development City par/by Jean Landry Planning/Planification 25 18 Révéler le « lieu-dit » urbain/Revealing the Urban Place par/by Michèle Gauthier + Lucie Careau Opinion 27 Are We Serious About Beauty?/Est-ce que la beauté nous tient à cœur ? by/par Joe Berridge The Last Word/Le mot de la fin 46 The CSLA 2016-2026/L’AAPC 2016-2026 by/par Rick Moore, President/président, CSLA/AAPC 29 Cover Image/Photographie de la couverture : David Yadlowski. -

Financial Statements of PROVINCE of ONTARIO

Financial Statements of PROVINCE OF ONTARIO COUNCIL FOR THE ARTS (OPERATING AS ONTARIO ARTS COUNCIL) And Independent Auditors' Report thereon Year ended March 31, 2020 Province of Ontario Council for the Arts Management’s Responsibility for Financial Information The accompanying financial statements of the Province of Ontario Council for the Arts (the OAC) are the responsibility of management and have been prepared in accordance with Canadian public sector accounting standards. Management maintains a system of internal controls designed to provide reasonable assurance that financial information is accurate and that assets are protected. The Board of Directors ensures that management fulfils its responsibilities for financial reporting and internal control. The Finance and Audit Committee and the Board of Directors meet regularly to oversee the financial activities of the OAC, and annually to review the audited financial statements and the external auditor’s report thereon. The financial statements have been audited by the Office of the Auditor General of Ontario, whose responsibility is to express an opinion on the financial statements. The Auditor’s Report that appears as part of the financial statements outlines the scope of the Auditor’s examination and opinion. On behalf of management: Carolyn Vesely CEO Jerry Zhang Director of Finance and Administration July 17, 2020 INDEPENDENT AUDITOR’S REPORT To the Province of Ontario Council for the Arts and to the Minister of Heritage, Sport, Tourism and Culture Industries Opinion I have audited the financial statements of the Province of Ontario Council for the Arts (operating as Ontario Arts Council), which comprise the statement of financial position as at March 31, 2020 and the statements of operations and changes in fund balances, remeasurement gains and losses and cash flows for the year then ended, and notes to the financial statements, including a summary of significant accounting policies. -

Vital Arts and Public Value

Vital Arts and Public Value A BLUEPRINT FOR 2014-2020 Background For more than 50 years, the Ontario Arts Council (OAC) has played an essential role in supporting the growth and success of the province’s arts community. Established in 1963, OAC was founded with a mandate to foster the creation and production of art for the benefit of all Ontarians. Thanks to the Government of Ontario’s long-term investment in OAC, this province has built an extraordinarily robust arts infrastructure, one that is highly regarded in many other jurisdictions. OAC’s staff is responsible for more than 60 granting programs, while a 12-person volunteer board of directors, appointed by Ontario’s Lieutenant Governor in Council, oversees OAC policies and governance. OAC granting programs support arts disciplines, including craft, dance, literature, music, theatre, media arts and visual arts, as well as multidisciplinary arts. Other programs focus on particular kinds of arts activity – arts education, community arts – or on specific areas, such as skills development, audience development, touring, distribution and dissemination. Some OAC programs have distinct goals, such as Northern Arts, which is solely for artists and arts groups in northern Ontario, and Access and Career Development, which funds professional development activities for Aboriginal arts professionals and arts professionals of colour. OAC also has two offices that focus specifically on Aboriginal Arts and on Francophone Arts. An increasing number of Ontario artists and arts organizations are working across disciplines and moving seamlessly through various art forms. OAC’s programs are inclusive and respond to arts organizations and individual artists who are developing new ways of working, creating and presenting. -

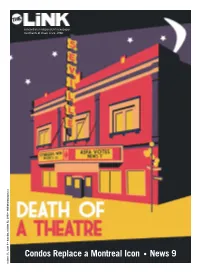

Layout 1 (Page 1)

concordia’s independent newspaper merchants of chaos since 1980 Condos Replace a Montreal Icon • News 9 volume 31, issue 9 • tuesday, october 12, 2010 • thelinknewspaper.ca volume 31, issue 9 • tuesday, BONDAGE AND BURLESQUE MURDERS IN SPACE MYTHS FOR ATHEISTS 4TH QUARTER COMEBACK YOUʼRE TAGGED FEATURES 12 FRINGE ARTS 13 LITERARY ARTS 17 SPORTS 22 OPINIONS 23 SPEAKER: ELIE WIESEL COMING TO CONCORDIA PAGE 03 Student Centre Reborn Student Union Opens Controversial Project from the Past • JUSTIN GIOVANNETTI has already been decided. In May 2009, a 79-page legal Although the Concordia Stu- agreement was signed between the dent Union is staying mum about CSU and the university that set out $43 its plans, the student centre project who would own, control and fi- million, the cost of the pro- nance the operations of the build- that was rejected by 72 per cent of posed student centre students at the March general elec- ing. Under the document, 32 per tion seems far from abandoned. cent of the building would belong “Students are already paying $2 to Concordia’s administration, towards this project, so we decided while students would control the that we have to tell them what the rest. centre is and why they are paying a “The student centre is a project fee levy,” said CSU VP External and by students, for students,” said Projects Adrien Severyns. Severyns. “The beauty of this proj- Over the past week, a number of ect is that students can decide what posters were put up by the CSU they want: a student-run café, an- $405 asking students what they would other bar, more study space, per student in a 90-credit pro- want a student centre to look like.