Master's Recital and Program Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musica Lirica

Musica Lirica Collezione n.1 Principale, in ordine alfabetico. 891. L.v.Beethoven, “Fidelio” ( Domingo- Meier; Barenboim) 892. L.v:Beethoven, “Fidelio” ( Altmeyer- Jerusalem- Nimsgern- Adam..; Kurt Masur) 893. Vincenzo Bellini, “I Capuleti e i Montecchi” (Pavarotti- Rinaldi- Aragall- Zaccaria; Abbado) 894. V.Bellini, “I Capuleti e i Montecchi” (Pavarotti- Rinaldi- Monachesi.; Abbado) 895. V.Bellini, “Norma” (Caballé- Domingo- Cossotto- Raimondi) 896. V.Bellini, “I Puritani” (Freni- Pavarotti- Bruscantini- Giaiotti; Riccardo Muti) 897. V.Bellini, “Norma” Sutherland- Bergonzi- Horne- Siepi; R:Bonynge) 898. V.Bellini, “La sonnanbula” (Sutherland- Pavarotti- Ghiaurov; R.Bonynge) 899. H.Berlioz, “La Damnation de Faust”, Parte I e II ( Rubio- Verreau- Roux; Igor Markevitch) 900. H.Berlioz, “La Damnation de Faust”, Parte III e IV 901. Alban Berg, “Wozzeck” ( Grundheber- Meier- Baker- Clark- Wottrich; Daniel Barenboim) 902. Georges Bizet, “Carmen” ( Verret- Lance- Garcisanz- Massard; Georges Pretre) 903. G.Bizet, “Carmen” (Price- Corelli- Freni; Herbert von Karajan) 904. G.Bizet, “Les Pecheurs de perles” (“I pescatori di perle”) e brani da “Ivan IV”. (Micheau- Gedda- Blanc; Pierre Dervaux) 905. Alfredo Catalani, “La Wally” (Tebaldi- Maionica- Gardino-Perotti- Prandelli; Arturo Basile) 906. Francesco Cilea, “L'Arlesiana” (Tassinari- Tagliavini- Galli- Silveri; Arturo Basile) 907. P.I.Ciaikovskij, “La Dama di Picche” (Freni- Atlantov-etc.) 908. P.I.Cajkovskij, “Evgenij Onegin” (Cernych- Mazurok-Sinjavskaja—Fedin; V. Fedoseev) 909. P.I.Tchaikovsky, “Eugene Onegin” (Alexander Orlov) 910. Luigi Cherubini, “Medea” (Callas- Vickers- Cossotto- Zaccaria; Nicola Rescigno) 911. Luigi Dallapiccola, “Il Prigioniero” ( Bryn-Julson- Hynninen- Haskin; Esa-Pekka Salonen) 912. Claude Debussy, “Pelléas et Mélisande” ( Dormoy- Command- Bacquier; Serge Baudo). 913. Gaetano Doninzetti, “La Favorita” (Bruson- Nave- Pavarotti, etc.) 914. -

Un Paysage Par Henri Duparc

Un paysage par Henri Duparc (1848 – 1933) Au sein de sa collection d’arts graphiques, le musée Lambinet conserve des pièces fort rares, parfois inédites, sans qu’aucun lien ne puisse être établi entre elles, et désolidarisées de fonds ou de grands ensembles auxquels elles auraient pu appartenir. C’est le cas d’un pastel sur papier chamois, de taille modeste (36 x 43cm), non signé, portant la mention manuscrite suivante : « pastel par Duparc, compositeur de mélodies magnifiques ». Donné à la ville de Versailles le 21 juin 1949 par Mme Gaston Pastre, par l’intermédiaire de Jean Gallotti, ce pastel reste énigmatique. Si l’activité de pastelliste du musicien est connue et citée par tous les littérateurs, surtout au moment où sa carrière de compositeur semble remise en cause par maladie nerveuse qui le frappe, aucune autre œuvre comparable n’a été portée à notre connaissance : aucune ne semble figurer à l’inventaire des collections publiques françaises, aucune n’apparaît même sur le marché de l’art. Pratiquée en amateur, cette activité anonyme est donc à envisager dans le cadre de la vie privée, et comme relevant de l’intime. Si l’on est enclin à croire l’inscription manuscrite de Mme Pastre, c’est aussi puisque M. Gaston Pastre, (1898-1939) écrivain, fut un contemporain et ami du compositeur. Plusieurs témoignages nous permettent en effet de savoir qu’Henri Duparc faisait don de tableaux ou de dessins à ses amis. Nous avons cherché enfin à entrer en contact avec les héritiers de la famille, qui pourront, nous l’espérons, montrer d’autres œuvres de la main de l’artiste. -

We Are Proud to Offer to You the Largest Catalog of Vocal Music in The

Dear Reader: We are proud to offer to you the largest catalog of vocal music in the world. It includes several thousand publications: classical,musical theatre, popular music, jazz,instructional publications, books,videos and DVDs. We feel sure that anyone who sings,no matter what the style of music, will find plenty of interesting and intriguing choices. Hal Leonard is distributor of several important publishers. The following have publications in the vocal catalog: Applause Books Associated Music Publishers Berklee Press Publications Leonard Bernstein Music Publishing Company Cherry Lane Music Company Creative Concepts DSCH Editions Durand E.B. Marks Music Editions Max Eschig Ricordi Editions Salabert G. Schirmer Sikorski Please take note on the contents page of some special features of the catalog: • Recent Vocal Publications – complete list of all titles released in 2001 and 2002, conveniently categorized for easy access • Index of Publications with Companion CDs – our ever expanding list of titles with recorded accompaniments • Copyright Guidelines for Music Teachers – get the facts about the laws in place that impact your life as a teacher and musician. We encourage you to visit our website: www.halleonard.com. From the main page,you can navigate to several other areas,including the Vocal page, which has updates about vocal publications. Searches for publications by title or composer are possible at the website. Complete table of contents can be found for many publications on the website. You may order any of the publications in this catalog from any music retailer. Our aim is always to serve the singers and teachers of the world in the very best way possible. -

La Sonnambula 3 Content

Florida Grand Opera gratefully recognizes the following donors who have provided support of its education programs. Study Guide 2012 / 2013 Batchelor MIAMI BEACH Foundation Inc. Dear Friends, Welcome to our exciting 2012-2013 season! Florida Grand Opera is pleased to present the magical world of opera to the diverse audience of © FLORIDA GRAND OPERA © FLORIDA South Florida. We begin our season with a classic Italian production of Giacomo Puccini’s La bohème. We continue with a supernatural singspiel, Mozart’s The Magic Flute and Vincenzo Bellini’s famous opera La sonnam- bula, with music from the bel canto tradition. The main stage season is completed with a timeless opera with Giuseppe Verdi’s La traviata. As our RHWIEWSRÁREPI[ILEZIEHHIHERI\XVESTIVEXSSYVWGLIHYPIMRSYV continuing efforts to be able to reach out to a newer and broader range of people in the community; a tango opera María de Buenoa Aires by Ástor Piazzolla. As a part of Florida Grand Opera’s Education Program and Stu- dent Dress Rehearsals, these informative and comprehensive study guides can help students better understand the opera through context and plot. )EGLSJXLIWIWXYH]KYMHIWEVIÁPPIH[MXLLMWXSVMGEPFEGOKVSYRHWWXSV]PMRI structures, a synopsis of the opera as well as a general history of Florida Grand Opera. Through this information, students can assess the plotline of each opera as well as gain an understanding of the why the librettos were written in their fashion. Florida Grand Opera believes that education for the arts is a vital enrich- QIRXXLEXQEOIWWXYHIRXW[IPPVSYRHIHERHLIPTWQEOIXLIMVPMZIWQSVI GYPXYVEPP]JYPÁPPMRK3RFILEPJSJXLI*PSVMHE+VERH3TIVE[ILSTIXLEX A message from these study guides will help students delve further into the opera. -

Cavalleria Rusticana Pagliacci

Pietro Mascagni - Ruggero Leoncavallo Cavalleria rusticana PIETRO MASCAGNI Òpera en un acte Llibret de Giovanni Targioni -Tozzetti i Guido Menasci Pagliacci RUGGERO LEONCAVALLO Òpera en dos actes Llibret i música de Ruggero Leoncavallo 5 - 22 de desembre Temporada 2019-2020 Temporada 1 Patronat de la Fundació del Gran Teatre del Liceu Comissió Executiva de la Fundació del Gran Teatre del Liceu President d’honor President Joaquim Torra Pla Salvador Alemany Mas President del patronat Vocals representants de la Generalitat de Catalunya Salvador Alemany Mas Mariàngela Vilallonga Vives, Francesc Vilaró Casalinas Vicepresidenta primera Vocals representants del Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte Mariàngela Vilallonga Vives Amaya de Miguel Toral, Antonio Garde Herce Vicepresident segon Vocals representants de l'Ajuntament de Barcelona Javier García Fernández Joan Subirats Humet, Marta Clarí Padrós Vicepresident tercer Vocal representant de la Diputació de Barcelona Joan Subirats Humet Joan Carles Garcia Cañizares Vicepresidenta quarta Vocals representants de la Societat del Gran Teatre del Liceu Núria Marín Martínez Javier Coll Olalla, Manuel Busquet Arrufat Vocals representants de la Generalitat de Catalunya Vocals representants del Consell de Mecenatge Francesc Vilaró Casalinas, Àngels Barbarà Fondevila, Àngels Jaume Giró Ribas, Luis Herrero Borque Ponsa Roca, Pilar Fernández Bozal Secretari Vocals representants del Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte Joaquim Badia Armengol Santiago Fisas Ayxelà, Amaya de Miguel Toral, Santiago de Director general -

Samuel Barber (1910-1981)

Catalogue thématique des œuvres I. Musique orchestrale Année Œuvre Opus 1931 Ouverture « The School for Scandal » 5 1933 Music for a Scene from Shelley 7 1936 Symphonie in One Movement 9 Adagio pour orchestre à cordes [original : deuxième mouvement du 1938 11 Quatuor à cordes op.11, 1936] 1937 Essay for orchestra 12 1939 Concerto pour violon & orchestre 14 1942 Second Essay for Orchestra 17 1943 Commando March - 1944 Serenade pour orchestre à cordes [original pour quatuor à cordes, 1928] 1 1944 Symphonie n°2 19 1944 Capricorn Concerto pour flûte, hautbois, trompette & cordes 21 1945 Concerto pour violoncelle & orchestre 22 1945 Horizon, pour vents, timbales, harpe & orchestre à cordes - Medea (Serpent Heart) [version révisée Cave of the Heart, 1947 ; arr. Suite 1946 23 de ballet, 1947] 1952 Souvenirs [original : piano à quatre mains, 1951] 28 1953 Medea’s Meditation and Dance of Vengeance 23a 1960 Toccata Festiva pour orgue & orchestre 36 1960 Die Natali - Chorale Preludes for Christmas 37 1962 Concerto pour piano & orchestre 38 1964 Night Flight [arr. deuxième mouvement de la Symphonie n°2] 19a 1971 Fadograph of a Yestern Scene 44 1978 Third Essay for Orchestra 47 Canzonetta pour hautbois & orchestre à cordes [op. posth., complété 1978 48 et orchestré par Charles Turner] © 2009 Capricorn Association des amis de Samuel Barber II. Musique instrumentale Année Œuvre Opus 3 Sketches pour piano : Lovesong / To My Steinway n°220601 / 1923-24 - Minuet Fresh from West Chester (Some Jazzings) pour piano : Poison Ivy 1925-26 - / Let’s Sit it Out, I’d Rather Watch 1931 Interlude I (« Adagio for Jeanne ») pour piano - 1932 Interlude II pour piano - 1932 Suite for Carillon - 1942-44 Excursions pour piano 20 1949 Sonate pour piano 26 Souvenirs pour piano à quatre mains [arr. -

28Apr2004p2.Pdf

144 NAXOS CATALOGUE 2004 | ALPHORN – BAROQUE ○○○○ ■ COLLECTIONS INVITATION TO THE DANCE Adam: Giselle (Acts I & II) • Delibes: Lakmé (Airs de ✦ ✦ danse) • Gounod: Faust • Ponchielli: La Gioconda ALPHORN (Dance of the Hours) • Weber: Invitation to the Dance ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Slovak RSO / Ondrej Lenárd . 8.550081 ■ ALPHORN CONCERTOS Daetwyler: Concerto for Alphorn and Orchestra • ■ RUSSIAN BALLET FAVOURITES Dialogue avec la nature for Alphorn, Piccolo and Glazunov: Raymonda (Grande valse–Pizzicato–Reprise Orchestra • Farkas: Concertino Rustico • L. Mozart: de la valse / Prélude et La Romanesca / Scène mimique / Sinfonia Pastorella Grand adagio / Grand pas espagnol) • Glière: The Red Jozsef Molnar, Alphorn / Capella Istropolitana / Slovak PO / Poppy (Coolies’ Dance / Phoenix–Adagio / Dance of the Urs Schneider . 8.555978 Chinese Women / Russian Sailors’ Dance) Khachaturian: Gayne (Sabre Dance) • Masquerade ✦ AMERICAN CLASSICS ✦ (Waltz) • Spartacus (Adagio of Spartacus and Phrygia) Prokofiev: Romeo and Juliet (Morning Dance / Masks / # DREAMER Dance of the Knights / Gavotte / Balcony Scene / A Portrait of Langston Hughes Romeo’s Variation / Love Dance / Act II Finale) Berger: Four Songs of Langston Hughes: Carolina Cabin Shostakovich: Age of Gold (Polka) •␣ Bonds: The Negro Speaks of Rivers • Three Dream Various artists . 8.554063 Portraits: Minstrel Man •␣ Burleigh: Lovely, Dark and Lonely One •␣ Davison: Fields of Wonder: In Time of ✦ ✦ Silver Rain •␣ Gordon: Genius Child: My People • BAROQUE Hughes: Evil • Madam and the Census Taker • My ■ BAROQUE FAVOURITES People • Negro • Sunday Morning Prophecy • Still Here J.S. Bach: ‘In dulci jubilo’, BWV 729 • ‘Nun komm, der •␣ Sylvester's Dying Bed • The Weary Blues •␣ Musto: Heiden Heiland’, BWV 659 • ‘O Haupt voll Blut und Shadow of the Blues: Island & Litany •␣ Owens: Heart on Wunden’ • Pastorale, BWV 590 • ‘Wachet auf’ (Cantata, the Wall: Heart •␣ Price: Song to the Dark Virgin BWV 140, No. -

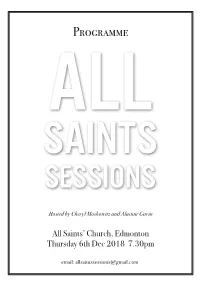

Programme ALL SAINTS SESSIONS

Programme ALL SAINTS SESSIONS Hosted by Cheryl Moskowitz and Alastair Gavin All Saints’ Church, Edmonton Thursday 6th Dec 2018 7.30pm email: [email protected] PROGRAMME Four arias after Vincenzo Bellini Richard Scott Ah! non credea mirarti Aria from “La Sonnambula” by Vincenzo Bellini Elinor Popham - Soprano Alastair Gavin - Electric Piano Reading Richard Ebben? Ne andrò lontana Aria from “La Wally” by Alfredo Catalani Elinor/Alastair 23 Words Cheryl Moskowitz Music by Alastair -------- INTERVAL -------- No One’s Rose A poem sequence by Richard and Cheryl 1) That Word All Over Again after Walt Whitman’s ‘Reconciliation’ - Cheryl 2) le jardin secret (from ‘Soho’) - Richard 3) Lines from ‘Psalm’ by Paul Celan – Cheryl 4) botany4boys - Richard 5) Making Our Own Garden (a Golden Shovel* after Paul Celan’s Psalms) - Cheryl 6) Oh My Soho! (section I) - Richard 7) Creation Story ‘Before there was anything there was…’ - Cheryl 8) Oh My Soho! (section IX) - Richard Music by Elinor & Alastair, concluding with Ma rendi pur content from “Composizioni da Camera” by Vincenzo Bellini * The Golden Shovel is a poetic form devised and given its name by American poet Terrance Hayes (who, with Richard, is also on this year’s TS Eliot prize shortlist). Part cento and part erasure, the form takes a line or a section from a poem by another poet and uses the words from that line or section as the end words in the new poem. The result is an honouring, a response to, and a reinvention of the original. Special thanks to Revd. Stuart Owen for his support and enthusiasm for this venture, Anthony Fisher for his generous donation of sound equipment, and of course to our very special guests Richard Scott and Elinor Popham. -

Volume 58, Number 07 (July 1940) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 7-1-1940 Volume 58, Number 07 (July 1940) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 58, Number 07 (July 1940)." , (1940). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/259 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ) . — < @ — — — —— . — — — — — — repertoire suggests the use of Summer enlarging ofthe £F\ •viert — I HOE Recent Additions mmsd(s m at qj d n fi coj to the Catalog of FAMOUS SONGS PUBLISHED MONTHLY By Theodore presser Co., Philadelphia, pa. H. E. KREHBIEL, Editor editorial and ADVISORY staff Volume Editor Price, $1.50 Each Tor ALTO DR. JAMES FRANCIS COOKE, Ditson Co. Hipsher, Associate Editor Oliver For SOPRANO outstanding writers on musical Dr. Edward Ellsworth America's • Mode by one of Contents William M. Felton. Music Editor music critic of leading metropolitan Contents subjects, for years the Guy McCoy volumes of Famous bongs Verna Arvev Or. Nicholas Doury Elizabeth Ciest journals, this collection in the four Beethoven. Good Friend, for Hullah. Three Fishers RoyPeery Went Dr. S. Fry George C. Knck Dr. Rob Jensen. -

New York Philharmonic Concerto for Clarinet and Orchestra / Third Essay for Orchestra, Opus 47 Mp3, Flac, Wma

New York Philharmonic Concerto For Clarinet And Orchestra / Third Essay For Orchestra, Opus 47 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Concerto For Clarinet And Orchestra / Third Essay For Orchestra, Opus 47 Country: US Style: Contemporary MP3 version RAR size: 1445 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1921 mb WMA version RAR size: 1482 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 924 Other Formats: MOD AIFF APE MIDI AUD DMF MP2 Tracklist Hide Credits Concerto For Clarinet And Orchestra –John Corigliano Composed By – John Corigliano 1 – I Cadenzas 8:54 II Elegy 2 – 8:36 Violin, Soloist – Sidney Harth 3 – III Antiphonal Toccata 8:59 Third Essay For Orchestra 4 –Samuel Barber 10:40 Composed By – Samuel Barber Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Recorded Anthology Of American Music, Inc. Copyright (c) – Recorded Anthology Of American Music, Inc. Mastered At – Masterdisk Recorded At – Avery Fisher Hall Published By – G. Schirmer Inc. Credits Artwork [Cover Art] – Theodoros Stamos Clarinet, Soloist – Stanley Drucker (tracks: A1 to B1) Conductor – Zubin Mehta Design [Cover Design] – Michael Sonino Engineer [Assistant Engineer] – William Messina*, Don Young , Hank Altman Engineer [Mixing Engineer] – Ray Moore Engineer [Recording Engineer] – Andrew Kazdin, Bud Graham Mastered By [Compact Disc Mastering] – E. Amelia Rogers*, Judith Sherman Orchestra – New York Philharmonic* Producer – Andrew Kazdin Notes World-premiere recording. Recorded at Avery Fisher Hall in New York. This disc was made possible with grants from the National Endowment for -

20 ANS/YRS Sm22-1 BI P02 Ads Sm21-6 BI Pxx 2016-08-31 4:06 PM Page 2

20 ANS/YRS sm22-1_BI_p01_LSMcover2testvector_wPDF_sm20-1_BI_pXX 2016-08-31 4:06 PM Page 1 sm22-1_BI_p02_ADs_sm21-6_BI_pXX 2016-08-31 4:06 PM Page 2 LUKAS GENIUŠAS QUEYRAS & MELNIKOV PRÉSENTE / PRESENTS HAGEN QUARTET PRAŽÁK QUARTET MUSICIANS FROM MARLBORO SAISON / SEASON HYESANG PARK BERNARD, THIBEAULT 2016-2017 ET TÉTREAULT LA MUSIQUE DANS TOUTE SA PURETÉ THE ESSENCE OF MUSIC JAMES EHNES YEFIM BRONFMAN ABONNEMENTS - SUBSCRIPTIONS ANDRÁS SCHIFF LOUIS LORTIE 514-845-0532 www.promusica.qc.ca sm22-1_BI_p03_TOCv2_sm21-6_BI_pXX 2016-08-31 4:07 PM Page 3 SOMMAIRE CONTENTS 15 INDUSTRY NEWS 16 La mélodie française / French Mélodies 18 Prix Arts-Affaires : Joanie Lapalme 20 Views of the World Music and Film Festival 21 Bryan Arias à Danse Danse 22 Angela Konrad, dramaturge 23 Prom Queen: The (Mega) Musical 24 Parents: La musique et le sport 25 LA RENTRÉE MUSICALE 40 JAZZ : Musiques à 8 42 LA RENTRÉE CULTURELLE 49 Shakespeare Reinvented 50 CRITIQUES / REVIEWS GUIDES 52 CALENDRIER RÉGIONAL REGIONAL CALENDAR 53 À VENIR / PREVIEWS 8 JAMES EHNES 46 Festivals d’automne / Fall Festivals CITÉ-MÉMOIRE 4 PHOTO BEN EALOVEGA RÉDACTEURS FONDATEURS / RÉDACTEURS EN CHEF / FINANCEMENT / FUNDRAISING BÉNÉVOLES / VOLUNTEERS contient des articles et des critiques ainsi FOUNDING EDITORS EDITORS-IN-CHIEF Natasha Beaudin Pearson Wah Wing Chan, Lilian I. Liganor, que des calendriers. LSM est publiée par La PUBLICITÉ / ADVERTISING Annie Prothin, Susan Marcus, Scène Musicale, un organisme sans but Wah Keung Chan, Philip Anson Wah Keung Chan, Caroline Rodgers lucratif. La Scena Musicale est la traduction RÉDACTEUR JAZZ / JAZZ EDITOR Natasha Beaudin Pearson, Marc Nicholas Roach italienne de La Scène Musicale. -

Understanding the Lirico-Spinto Soprano Voice Through the Repertoire of Giovane Scuola Composers

UNDERSTANDING THE LIRICO-SPINTO SOPRANO VOICE THROUGH THE REPERTOIRE OF GIOVANE SCUOLA COMPOSERS Youna Jang Hartgraves Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2017 APPROVED: Jeffrey Snider, Major Professor William Joyner, Committee Member Silvio De Santis, Committee Member Stephen Austin, Chair of the Division of Vocal Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Hartgraves, Youna Jang. Understanding the Lirico-Spinto Soprano Voice through the Repertoire of Giovane Scuola Composers. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2017, 53 pp., 10 tables, 6 figures, bibliography, 66 titles. As lirico-spinto soprano commonly indicates a soprano with a heavier voice than lyric soprano and a lighter voice than dramatic soprano, there are many problems in the assessment of the voice type. Lirico-spinto soprano is characterized differently by various scholars and sources offer contrasting and insufficient definitions. It is commonly understood as a pushed voice, as many interpret spingere as ‘to push.’ This dissertation shows that the meaning of spingere does not mean pushed in this context, but extended, thus making the voice type a hybrid of lyric soprano voice type that has qualities of extended temperament, timbre, color, and volume. This dissertation indicates that the lack of published anthologies on lirico-spinto soprano arias is a significant reason for the insufficient understanding of the lirico-spinto soprano voice. The post-Verdi Italian group of composers, giovane scuola, composed operas that required lirico-spinto soprano voices.