From the Corners of the Russian Novel: Minor Characters in Gogol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Children's Books & Illustrated Books

CHILDREN’S BOOKS & ILLUSTRATED BOOKS ALEPH-BET BOOKS, INC. 85 OLD MILL RIVER RD. POUND RIDGE, NY 10576 (914) 764 - 7410 CATALOGUE 94 ALEPH - BET BOOKS - TERMS OF SALE Helen and Marc Younger 85 Old Mill River Rd. Pound Ridge, NY 10576 phone 914-764-7410 fax 914-764-1356 www.alephbet.com Email - [email protected] POSTAGE: UNITED STATES. 1st book $8.00, $2.00 for each additional book. OVERSEAS shipped by air at cost. PAYMENTS: Due with order. Libraries and those known to us will be billed. PHONE orders 9am to 10pm e.s.t. Phone Machine orders are secure. CREDIT CARDS: VISA, Mastercard, American Express. Please provide billing address. RETURNS - Returnable for any reason within 1 week of receipt for refund less shipping costs provided prior notice is received and items are shipped fastest method insured VISITS welcome by appointment. We are 1 hour north of New York City near New Canaan, CT. Our full stock of 8000 collectible and rare books is on view and available. Not all of our stock is on our web site COVER ILLUSTRATION - #307 - ORIGINAL ART BY MAUD HUMPHREY FOR GALLANT LITTLE PATRIOTS #357 - Meggendorfer Das Puppenhaus (The Doll House) #357 - Meggendorfer Das Puppenhaus #195 - Detmold Arabian Nights #526 - Dr. Seuss original art #326 - Dorothy Lathrop drawing - Kou Hsiung (Pekingese) #265 - The Magic Cube - 19th century (ca. 1840) educational game Helen & Marc Younger Pg 3 [email protected] THE ITEMS IN THIS CATALOGUE WILL NOT BE ON RARE TUCK RAG “BLACK” ABC 5. ABC. (BLACK) MY HONEY OUR WEB SITE FOR A FEW WEEKS. -

Frank Zappa and His Conception of Civilization Phaze Iii

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2018 FRANK ZAPPA AND HIS CONCEPTION OF CIVILIZATION PHAZE III Jeffrey Daniel Jones University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2018.031 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Jones, Jeffrey Daniel, "FRANK ZAPPA AND HIS CONCEPTION OF CIVILIZATION PHAZE III" (2018). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 108. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/108 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

Title Author Gr Elementary Approved Literature List by Grade

Elementary Approved Literature List by Grade Title Author Gr Alison’s Wings, 1996 Bauer, Marion Dane K All About Seeds Kuchalla, Susan K Alpha Kids Series Sundance Publishers K Amphibians Are Animals Holloway, Judith K An Extraordinary Egg Lionni, Leo K Animal Strike at the Zoo Wilson, Karma K Animals Carle, Eric K Animals At Night Peters, Ralph K Anno's Journey (BOE approved Nov 2015) Anno, Mitsumasa K Ant and the Grasshopper, The: An Aesop's Fable Paxton, Tom K (BOE approved Nov 2015) Autumn Leaves are Falling Fleming, Maria K Baby Animals Kuchalla, Susan K Baby Whales Drink Milk Esbensen, Barbara Juster K Bad Case of Stripes, A Shannon, David K Barn Cat Saul, Carol P. K Bear and the Fly, The Winter, Paula K Bear Ate Your Sandwich, The (BOE Approved Apr 2016) Sarcone-Roach, Julia K Bear Shadow Asch, Frank K Bear’s Busy Year, 1990 Leonard, Marcia K Bear’s New Friend Wilson, Karma K Bears Kuchalla, Susan K Bedtime For Frances Hoban, Russell K Berenstain Bear’s New Pup, The Berenstain, Stan K Big Red Apple Johnston, Tony K updated April 15, 2016 *previously approved at higher grade level 1 Elementary Approved Literature List by Grade Title Author Gr Big Shark’s Lost Tooth Metzger, Steve K Big Snow, The Hader, Berta K Bird Watch Jennings, Terry K Birds Kuchalla, Susan K Birds Nests Curran, Eileen K Boom Town, 1998 Levitin, Sonia K Buildings Chessen, Betsy K Button Soup Disney, Walt K Buzz Said the Bee Lewison, Wendy K Case of the Two Masked Robbers, The Hoban, Lillian K Celebrating Martin Luther King Jr. -

King-Salter2020.Pdf (1.693Mb)

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Dostoevsky’s Storm and Stress Notes from Underground and the Psychological Foundations of Utopia John Luke King-Salter PhD Comparative Literature University of Edinburgh 2019 Lay Summary The goal of this dissertation is to combine philosophical and literary scholarship to arrive at a new interpretation of Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground. In this novel, Dostoevsky argues against the Russian socialists of the early 1860s, and attacks their ideal of a socialist utopia in particular. Dostoevsky’s argument is obscure and difficult to understand, but it seems to depend upon the way he understands the interaction between psychology and politics, or, in other words, the way in which he thinks the health of a society depends upon the psychological health of its members. It is usually thought that Dostoevsky’s problem with socialism is that it curtails individual liber- ties to an unacceptable degree, and that the citizens of a socialist utopia would be frustrated by the lack of freedom. -

Refractions of Rome in the Russian Political Imagination by Olga Greco

From Triumphal Gates to Triumphant Rotting: Refractions of Rome in the Russian Political Imagination by Olga Greco A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Comparative Literature) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Valerie A. Kivelson, Chair Assistant Professor Paolo Asso Associate Professor Basil J. Dufallo Assistant Professor Benjamin B. Paloff With much gratitude to Valerie Kivelson, for her unflagging support, to Yana, for her coffee and tangerines, and to the Prawns, for keeping me sane. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication ............................................................................................................................... ii Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 1 Chapter I. Writing Empire: Lomonosov’s Rivalry with Imperial Rome ................................... 31 II. Qualifying Empire: Morals and Ethics of Derzhavin’s Romans ............................... 76 III. Freedom, Tyrannicide, and Roman Heroes in the Works of Pushkin and Ryleev .. 122 IV. Ivan Goncharov’s Oblomov and the Rejection of the Political [Rome] .................. 175 V. Blok, Catiline, and the Decomposition of Empire .................................................. 222 Conclusion ........................................................................................................................... 271 Bibliography ....................................................................................................................... -

Vinogradov I.A. 2018-2.Indd

ПРОБЛЕМЫ ИСТОРИЧЕСКОЙ ПОЭТИКИ 2018 Том 16 № 2 DOI 10.15393/j9.art.2018.5181 УД К 821.161.1.09“18” Игорь Алексеевич Виноградов Институт мировой литературы им. А. М. Горького Российской академии наук (Москва, Российская Федерация) [email protected] ЛИТЕРАТУРНАЯ ПРОПОВЕДЬ Н. В. ГОГОЛЯ: PRO ET CONTRA Аннотация. Статья посвящена изучению противоречивого отношения к наследию Н. В. Гоголя в последующей русской литературе. Анализиру- ется конфликт между содержанием творчества писателя и пафосом его ближайших «продолжателей», представителей так называемой «натураль- ной школы», объединившей литераторов западнического направления, во главе с В. Г. Белинским и Н. А. Некрасовым. Обозначена роль П. В. Аннен- кова, В. П. Боткина, И. С. Тургенева, Н. Г. Чернышевского и др. в антиго- голевской кампании, развернутой в 1847 г. Белинским по поводу выхода в свет «Выбранных мест из переписки с друзьями». Подробно рассматри- вается особое отношение к гоголевским традициям Ф. М. Достоевского. Детально освещена история статьи Тургенева о смерти Гоголя 1852 г. Уточняются истоки известного сатирического выпада тургеневского героя Базарова в адрес Гоголя в «Отцах и детях». Представлена объективная картина гоголевских оценок произведений Тургенева. Впервые изложена история возникновения и развития «литературоцентризма» отечественной культуры XIX–XX вв. Ключевые слова: Н. В. Гоголь, творчество, интерпретация, традиции, профетизм, литературоцентризм, проповедь, «Выбранные места из пере- писки с друзьями», западничество, славянофильство, полемика, пародия *** аследование Н. В. Гоголю в русской литературе имеет Ндолгую и плодотворную традицию, но начинается с кон- фликта. Конфликт заключается в глубоком противоречии между содержанием творчества Гоголя и пафосом его бли- жайших «продолжателей», представителей так называемой «натуральной школы», объединившей литераторов западни- ческого направления, во главе с В. Г. Белинским и Н. А. -

Teaching the Short Story: a Guide to Using Stories from Around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 397 453 CS 215 435 AUTHOR Neumann, Bonnie H., Ed.; McDonnell, Helen M., Ed. TITLE Teaching the Short Story: A Guide to Using Stories from around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1947-6 PUB DATE 96 NOTE 311p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 19476: $15.95 members, $21.95 nonmembers). PUB 'TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) Collected Works General (020) Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Authors; Higher Education; High Schools; *Literary Criticism; Literary Devices; *Literature Appreciation; Multicultural Education; *Short Stories; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS *Comparative Literature; *Literature in Translation; Response to Literature ABSTRACT An innovative and practical resource for teachers looking to move beyond English and American works, this book explores 175 highly teachable short stories from nearly 50 countries, highlighting the work of recognized authors from practically every continent, authors such as Chinua Achebe, Anita Desai, Nadine Gordimer, Milan Kundera, Isak Dinesen, Octavio Paz, Jorge Amado, and Yukio Mishima. The stories in the book were selected and annotated by experienced teachers, and include information about the author, a synopsis of the story, and comparisons to frequently anthologized stories and readily available literary and artistic works. Also provided are six practical indexes, including those'that help teachers select short stories by title, country of origin, English-languag- source, comparison by themes, or comparison by literary devices. The final index, the cross-reference index, summarizes all the comparative material cited within the book,with the titles of annotated books appearing in capital letters. -

Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films Through Grotesque Aesthetics

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 9-10-2015 12:00 AM Who's the Fairest of Them All? Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films through Grotesque Aesthetics Leah Persaud The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Angela Borchert The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Leah Persaud 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Persaud, Leah, "Who's the Fairest of Them All? Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films through Grotesque Aesthetics" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3244. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3244 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHO’S THE FAIREST OF THEM ALL? DEFINING AND SUBVERTING THE FEMALE BEAUTY IDEAL IN FAIRY TALE NARRATIVES AND FILMS THROUGH GROTESQUE AESTHETICS (Thesis format: Monograph) by Leah Persaud Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Leah Persaud 2015 Abstract This thesis seeks to explore the ways in which women and beauty are depicted in the fairy tales of Giambattista Basile, the Grimm Brothers, and 21st century fairy tale films. -

The Rise of Bulgarian Nationalism and Russia's Influence Upon It

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2014 The rise of Bulgarian nationalism and Russia's influence upon it. Lin Wenshuang University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Wenshuang, Lin, "The rise of Bulgarian nationalism and Russia's influence upon it." (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1548. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1548 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RISE OF BULGARIAN NATIONALISM AND RUSSIA‘S INFLUENCE UPON IT by Lin Wenshuang B. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 1997 M. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 2002 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2014 Copyright © 2014 by Lin Wenshuang All Rights Reserved THE RISE OF BULGARIAN NATIONALISM AND RUSSIA‘S INFLUENCE UPON IT by Lin Wenshuang B. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 1997 M. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 2002 A Dissertation Approved on April 1, 2014 By the following Dissertation Committee __________________________________ Prof. -

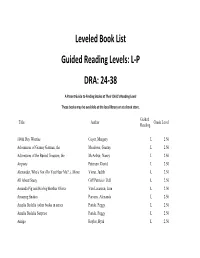

Leveled Book List Guided Reading Levels: L-P DRA: 24-38

Leveled Book List Guided Reading Levels: L‐P DRA: 24‐38 A Parent Guide to Finding Books at Their Child’s Reading Level These books may be available at the local library or at a book store. Guided Title Author Grade Level Reading 100th Day Worries Cuyer, Margery L 2.50 Adventures of Granny Gatman, the Meadows, Granny L 2.50 Adventures of the Buried Treasure, the McArthur, Nancy L 2.50 Airports Petersen, David L 2.50 Alexander, Who's Not (Do You Hear Me?..)..Move Viorst, Judith L 2.50 All About Stacy Giff Patricia / Dell L 2.50 Amanda Pig and Her big Brother Oliver Van Leeuwen, Jean L 2.50 Amazing Snakes Parsons, Alexanda L 2.50 Amelia Bedelia (other books in series Parish, Peggy L 2.50 Amelia Bedelia Surprise Parish, Peggy L 2.50 Amigo Baylor, Byrd L 2.50 Anansi the Spider McDermott, Gerald L 2.50 Animal Tracks Dorros, Arthur L 2.50 Annabel the Actress Starring in Gorilla My Dream Conford, Ellen L 2.50 Anna's Garden Songs Steele, Mary Q. L 2.50 Annie and the Old One Miles, Miska L 2.50 Annie Bananie Mover to Barry Avenue Komaiko, Leah L 2.50 Arthur Meets the President Brown, Marc L 2.50 Artic Son George, Jean Craighead L 2.50 Bad Luck Penny, the O'Connor Jane L 2.50 Bad, Bad Bunnies Delton, Judy L 2.50 Beans on the Roof Byare, Betsy L 2.50 Bear's Dream Slingsby, Janet L 2.50 Ben's Trumpet Isadora, Rachel L 2.50 B-E-S-T Friends Giff Patricia / Dell L 2.50 Best Loved doll, the Caudill, Rebecca L 2.50 Best Older Sister, the Choi, Sook Nyul L 2.50 Best Worst Day, the Graves, Bonnie L 2.50 Big Al Yoshi, Andrew L 2.50 Big Box of Memories Delton, -

Ulyanovsk State Technical University 1 Content

Ulyanovsk State Technical University 1 Content The city of Ulyanovsk 4 International Cooperation 19 History of Ulyanovsk 6 Social and Cultural Activity 20 Ulyanovsk Today 8 Health and Sports 21 Ulyanovsk State University Awards 22 Technical University 10 Research Centres Facts & Numbers 12 & Laboratories 23 Higher Education 14 UlSTU in progress... 24 Traditions of the University 16 Plans for Future 25 Campus map 17 Contact Information 26 Library 18 3 The city of Ulyanovsk Ulyanovsk is a fascinating city with unique geography, culture, economy and a rich history. Ulyanovsk is an administrative center of the Ulyanovsk region. It is located at the middle of European Russia in the Volga Ulyanovsk is the 20th in Russian population ranking Upland on the banks of the Volga City with a humid continental climate (meaning hot summers and cold winters) and Sviyaga rivers (893 km southeast of Moscow). Coordinates: 54°19′N 48°22′E Population: 637 300 inhabitants (January, 2011) Ulyanovsk is an important Time zone: UTC+4 (M) Ethnic russians: 75%, tatars: 12%, transport node between European composition: chuvash: 8%, mordvins: 3%, others: 2% and Asian Russia. Dialing code: +7 8422 Density: 1185 people/km2 Total area: 622,46 km². Religions: Orthodoxy, Islam A view of the Lenin Memorial building 4 in Ulyanovsk (the right bank of the Volga river) 5 Vladimir Ulyanov (Lenin) is a world-famous History personality, the leader of 1917 Russian revolution. Lenin was born on April, 22 1870 of Ulyanovsk in Simbirsk and lived there the earliest 17 years of his life. Ulyanovsk was founded as a fortress in 1648 by the boyar Bogdan Khitrovo and deacon Grigory Kunakov. -

Between Moscow and Baku: National Literatures at the 1934 Congress of Soviet Writers

Between Moscow and Baku: National Literatures at the 1934 Congress of Soviet Writers by Kathryn Douglas Schild A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Harsha Ram, Chair Professor Irina Paperno Professor Yuri Slezkine Fall 2010 ABSTRACT Between Moscow and Baku: National Literatures at the 1934 Congress of Soviet Writers by Kathryn Douglas Schild Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures University of California, Berkeley Professor Harsha Ram, Chair The breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991 reminded many that “Soviet” and “Russian” were not synonymous, but this distinction continues to be overlooked when discussing Soviet literature. Like the Soviet Union, Soviet literature was a consciously multinational, multiethnic project. This dissertation approaches Soviet literature in its broadest sense – as a cultural field incorporating texts, institutions, theories, and practices such as writing, editing, reading, canonization, education, performance, and translation. It uses archival materials to analyze how Soviet literary institutions combined Russia’s literary heritage, the doctrine of socialist realism, and nationalities policy to conceptualize the national literatures, a term used to define the literatures of the non-Russian peripheries. It then explores how such conceptions functioned in practice in the early 1930s, in both Moscow and Baku, the capital of Soviet Azerbaijan. Although the debates over national literatures started well before the Revolution, this study focuses on 1932-34 as the period when they crystallized under the leadership of the Union of Soviet Writers.