By Design Lwo Jima and the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Park Sites of the George Washington Memorial Parkway

National Park Service Park News and Events U.S. Department of the Interior Virginia, Maryland and Potomac Gorge Bulletin Washington, D.C. Fall and Winter 2017 - 2018 The official newspaper of the George Washington Memorial Parkway Edition George Washington Memorial Parkway Visitor Guide Drive. Play. Learn. www.nps.gov/gwmp What’s Inside: National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior For Your Information ..................................................................3 George Washington Important Phone Numbers .........................................................3 Memorial Parkway Become a Volunteer .....................................................................3 Park Offices Sites of George Washington Memorial Parkway ..................... 4–7 Alex Romero, Superintendent Partners and Concessionaires ............................................... 8–10 Blanca Alvarez Stransky, Deputy Superintendent Articles .................................................................................11–12 Aaron LaRocca, Events ........................................................................................13 Chief of Staff Ruben Rodriguez, Park Map .............................................................................. 14-15 Safety Officer Specialist Activities at Your Fingertips ...................................................... 16 Mark Maloy, Visual Information Specialist Dawn Phillips, Administrative Officer Message from the Office of the Superintendent Jason Newman, Chief of Lands, Planning and Dear Park Visitors, -

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments No. Name Address CHC No. CF No. Adopted Community Plan Area CD Notes 1 Leonis Adobe 23537 Calabasas Road 08/06/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 3 Woodland Hills - West Hills 2 Bolton Hall 10116 Commerce Avenue & 7157 08/06/1962 Sunland - Tujunga - Lake View 7 Valmont Street Terrace - Shadow Hills - East La Tuna Canyon 3 Plaza Church 535 North Main Street and 100-110 08/06/1962 Central City 14 La Iglesia de Nuestra Cesar Chavez Avenue Señora la Reina de Los Angeles (The Church of Our Lady the Queen of Angels) 4 Angel's Flight 4th Street & Hill Street 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Dismantled May 1969; Moved to Hill Street between 3rd Street and 4th Street, February 1996 5 The Salt Box 339 South Bunker Hill Avenue (Now 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Moved from 339 Hope Street) South Bunker Hill Avenue (now Hope Street) to Heritage Square; destroyed by fire 1969 6 Bradbury Building 300-310 South Broadway and 216- 09/21/1962 Central City 14 224 West 3rd Street 7 Romulo Pico Adobe (Rancho 10940 North Sepulveda Boulevard 09/21/1962 Mission Hills - Panorama City - 7 Romulo) North Hills 8 Foy House 1335-1341 1/2 Carroll Avenue 09/21/1962 Silver Lake - Echo Park - 1 Elysian Valley 9 Shadow Ranch House 22633 Vanowen Street 11/02/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 12 Woodland Hills - West Hills 10 Eagle Rock Eagle Rock View Drive, North 11/16/1962 Northeast Los Angeles 14 Figueroa (Terminus), 72-77 Patrician Way, and 7650-7694 Scholl Canyon Road 11 The Rochester (West Temple 1012 West Temple Street 01/04/1963 Westlake 1 Demolished February Apartments) 14, 1979 12 Hollyhock House 4800 Hollywood Boulevard 01/04/1963 Hollywood 13 13 Rocha House 2400 Shenandoah Street 01/28/1963 West Adams - Baldwin Hills - 10 Leimert City of Los Angeles May 5, 2021 Page 1 of 60 Department of City Planning No. -

Netherlands Carillon Rehabilitation

Delegated Action of the Executive Director PROJECT NCPC FILE NUMBER Netherlands Carillon Rehabilitation 7969 Arlington Ridge Park Arlington, Virginia NCPC MAP FILE NUMBER 1.61(73.10)44718 SUBMITTED BY United States Department of the Interior ACTION TAKEN National Park Service Approve as requested REVIEW AUTHORITY Advisory Per 40 U.S.C. § 8722(b)(1) The National Park Service (NPS) has submitted for Commission review site and building plans for the Netherlands Carillon in Arlington Ridge Park in Arlington, Virginia. The Netherlands Carillon is a 127-foot-tall open steel historic structure that sits within Arlington Ridge Park, near the U.S. Marine Corps War Memorial and Arlington National Cemetery. It was a gift from the people of the Netherlands to the people of the United States in gratitude for American aid during and after World War II, and symbolizes friendship between the two countries, and their common allegiance to the principles of freedom, justice, and democracy. The carillon is cast from a bronze alloy and features 50 bells, each carrying an emblem and verse representing a group within Dutch society. The original gift of the bells was conceived in 1950, which were completed and shipped to the United States in 1954 and hung in a temporary structure in West Potomac Park. The current structure was constructed in 1960 by Dutch architect Joost W.C. Boks, and is recognized as one of the first modernist monuments constructed in the region. The structure sits within a square plaza, and is flanked by two bronze lion sculptures. To the east of the plaza is a tulip library, also a gift from the Dutch, which was planted in 1964. -

Hawaii Waimea Valley B-1 MCCS & SM&SP B-2 Driving Regs B-3 Menu B-5 Word to Pass B-7 Great Aloha Run C-1 Sports Briefs C-2 the Bottom Line C-3

INSIDE National Anthem A-2 2/3 Air Drop A-3 Recruiting Duty A-6 Hawaii Waimea Valley B-1 MCCS & SM&SP B-2 Driving Regs B-3 Menu B-5 Word to Pass B-7 Great Aloha Run C-1 Sports Briefs C-2 The Bottom Line C-3 High School Cadets D-1 MVMOLUME 35, NUMBER 8 ARINEARINEWWW.MCBH.USMC.MIL FEBRUARY 25, 2005 3/3 helps secure clinic Marines maintain security, enable Afghan citizens to receive medical treatment Capt. Juanita Chang Combined Joint Task Force 76 KHOST PROVINCE, Afghanistan — Nearly 1,000 people came to Khilbasat village to see if the announcements they heard over a loud speaker were true. They heard broadcasts that coalition forces would be providing free medical care for local residents. Neither they, nor some of the coalition soldiers, could believe what they saw. “The people are really happy that Americans are here today,” said a local boy in broken English, talking from over a stone wall to a Marine who was pulling guard duty. “I am from a third-world country, but this was very shocking for me to see,” said Spc. Thia T. Valenzuela, who moved to the United States from Guyana in 2001, joined the United States Army the same year, and now calls Decatur, Ga., home. “While I was de-worming them I was looking at their teeth. They were all rotten and so unhealthy,” said Valenzuela, a dental assistant from Company C, 725th Main Support Battalion stationed out of Schofield Barracks, Hawaii. “It was so shocking to see all the children not wearing shoes,” Valenzuela said, this being her first time out of the secure military facility, or “outside the wire” as service members in Afghanistan refer to it. -

From Flags of Our Fathers to Letters from Iwo Jima: Clint Eastwood's Balancing of Japanese and American Perspectives

Volume 4 | Issue 12 | Article ID 2290 | Dec 02, 2006 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus From Flags of Our Fathers to Letters From Iwo Jima: Clint Eastwood's Balancing of Japanese and American Perspectives Aaron Gerow From Flags of Our Fathers to Letters From Iwo Jima: Clint Eastwood’s Balancing of Japanese and American Perspectives By Aaron Gerow History, like the cinema, can often be a matter of perspective. That’s why Clint Eastwood’s decision to narrate the Battle of Iwo Jima from both the American and the Japanese point of view is not really new; it had been done before in Tora Tora Tora (1970), for instance. But by dividing these perspectives in different films directed at Japanese and international audiences, Eastwood makes history not merely an issue of which side you are on, but of how to look at history itself. Flags of Our Fathers, the American version, is less about the battle than the memory of war, focusing in particular on how nations compulsively create heroes when they need them (like with the soldiers who raised the flag on Iwo Jima) and forget them later when they don’t. Instead of giving the national narrative of bravery in capturing Iwo Jima, the film shows how such stories are manufactured by media and governments to further the aims of the country, whatever may be the truth or the 1 4 | 12 | 0 APJ | JF feelings of the individual soldiers. Against the And some of the figures are fascinating. constructed nature of public heroism, Eastwood Kuribayashi (Watanabe Ken) had studied in the poses the private real bonds between men; United States, wrote loving letters to his son against public memory he focuses on personal with comic illustrations, and protected his men trauma. -

Directory Carillons

Directory of Carillons 2014 The Guild of Carillonneurs in North America Foreword This compilation, published annually by the Guild of Carillonneurs in North America (GCNA), includes cast-bell instruments in Canada, Mexico, and the United States. The listings are alphabetized by state or province and municipality. Part I is a listing of carillons. Part II lists cast- bell instruments which are activated by a motorized mechanism where the performer uses an ivory keyboard similar to that of a piano or organ. Additional information on carillons and other bell instruments in North America may be found on the GCNA website, http://gcna.org, or the website of Carl Zimmerman, http://towerbells.org. The information and photos in this booklet are courtesy of the respective institutions, carillonneurs, and contact people, or available either in the public domain or under the Creative Commons License. To request printed copies or to submit updates and corrections, please contact Tiffany Ng ([email protected]). Directory entry format: City Name of carillon Name of building Name of place/institution Street/mailing address Date(s) of instrument completion/expansion: founder(s) (# of bells) Player’s name and contact information Contact person (if different from player) Website What is a Carillon? A carillon is a musical instrument consisting of at least two octaves of carillon bells arranged in chromatic series and played from a keyboard permitting control of expression through variation of touch. A carillon bell is a cast bronze cup-shaped bell whose partial tones are in such harmonious relationship to each other as to permit many such bells to be sounded together in varied chords with harmonious and concordant effect. -

I.S. Antarctic Projects Officer

I.S. ANTARCTIC PROJECTS OFFICER VOLUME III NUMBER :J DECEMBER 1961 [December 14, 19111. At three in the afternoon a simultaneous "Flt" rang out from the drivers. They had carefully examined their sledge-meters, and they all showed the full distance -- our Pole by reckoning. The goal was reached, the journey ended. Roald Amundsen, The South Pole, vol. II, p. 121. Thursday, December 14 (1911]. However, we all lunched together after a satisfactory mornings work. In the after- noon we did still better, and camped at 6.30 with a very marked change in the land bear- ings. We must have come 11 or 12 miles (stat.). We got fearfully hot on the march, sweated through everything and stripped off jerseys. The result is we are pretty cold and clammy now, but escape from the soft snow and a good march compensate every discomfort. Captain Robert F. Scott, Scotts Last Expedition, arranged by Leonard Huxley, vol. I, p. 346. Volume III, No. 4 December 1961 CONTENTS The Month in Review 1 Ellsworth Land Traverse 1 Topo South Completed 3 Sky-Hi Station Established 4 Ninth Troop Carrier Squadron Commended 5 Note Recovered 6 Overland Expeditions to the South Pole (1910-1961) 7 Tribute to an Explorer, by James E. Mooney 11 The Hydrographic Office in the Antarctic 13 Antarctic Chronology, 1961-62 14 Antarctic Visitors 16 Official Foreign Representative Exchange Program 18 Material for this issue of the Bulletin was adapted from press releases issued by the Department of Defense and the National Sci- enoe Foundation and from incoming dispatches. -

The Mid-South Flyer South Flyer

The MidMid----SouthSouth Flyer January-February 2014 A Publication of the Mid-South Chapter of the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society, Inc January program Riding the rails with Jack Ferris and company It’s every rail fan’s dream to one day own your own pri- vate railroad car, complete with rear platform and all of the amenities. But own your own train? Well yes, if you happen to be Jack Ferris, the late father of Mid-South member Dan Ferris, The son of an Erie engi- neer and a very successful Midwest industrialist, Jack had both the penchant and the means to enjoy rail travel aboard his own private car train. That’s train, as in eight Pullman cars of various pedigrees, from the handsome Capital Heights observation-lounge- sleeper (pictured at right with Jack and wife Eleanor on the platform), to the Wabash Valley dining car, to the luxu- rious buffet-lounge-sleeper Dover Plains . Painted in a handsome dark blue color with a gold band below the windows (shades of L&N!) , Jack’s private car operation was officially named Private Rail Cars, Inc . based in Ft. Wayne, Indiana. To make it even more official, the company had it’s own listing in the Official Register of Passenger Train Equipment. One of PRC’s cars, the Clover Colony , was literally saved by son Dan from a scrap yard in, of all places, Bir- mingham! Because of his rescue, “The Clover, ” as Dan affectionately calls the car, survived another half century and today runs in excursion service at the Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum in Chattanooga. -

Genealogical Sketch of the Descendants of Samuel Spencer Of

C)\\vA CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 924 096 785 351 Cornell University Library The original of this bool< is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924096785351 In compliance with current copyright law, Cornell University Library produced this replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Standard Z39.48-1992 to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. 2003 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY : GENEALOGICAL SKETCH OF THE DESCENDANTS OF Samuel Spencer OF PENNSYLVANIA BY HOWARD M. JENKINS AUTHOR OF " HISTORICAL COLLECTIONS RELATING TO GWYNEDD," VOLUME ONE, "MEMORIAL HISTORY OF PHILADELPHIA," ETC., ETC. |)l)Uabei|it)ia FERRIS & LEACH 29 North Seventh Street 1904 . CONTENTS. Page I. Samuel Spencer, Immigrant, I 11. John Spencer, of Bucks County, II III. Samuel Spencer's Wife : The Whittons, H IV. Samuel Spencer, 2nd, 22 V. William. Spencer, of Bucks, 36 VI. The Spencer Genealogy 1 First and Second Generations, 2. Third Generation, J. Fourth Generation, 79 ^. Fifth Generation, 114. J. Sixth Generation, 175 6. Seventh Generation, . 225 VII. Supplementary .... 233 ' ADDITIONS AND CORRECTIONS. Page 32, third line, "adjourned" should be, of course, "adjoined." Page 33, footnote, the date 1877 should read 1787. " " Page 37, twelfth line from bottom, Three Tons should be "Three Tuns. ' Page 61, Hannah (Shoemaker) Shoemaker, Owen's second wife, must have been a grand-niece, not cousin, of Gaynor and Eliza. Thus : Joseph Lukens and Elizabeth Spencer. Hannah, m. Shoemaker. Gaynor Eliza Other children. I Charles Shoemaker Hannah, m. Owen S. Page 62, the name Horsham is divided at end of line as if pronounced Hor-sham ; the pronunciation is Hors-ham. -

Native Americans and World War II

Reemergence of the “Vanishing Americans” - Native Americans and World War II “War Department officials maintained that if the entire population had enlisted in the same proportion as Indians, the response would have rendered Selective Service unnecessary.” – Lt. Col. Thomas D. Morgan Overview During World War II, all Americans banded together to help defeat the Axis powers. In this lesson, students will learn about the various contributions and sacrifices made by Native Americans during and after World War II. After learning the Native American response to the attack on Pearl Harbor via a PowerPoint centered discussion, students will complete a jigsaw activity where they learn about various aspects of the Native American experience during and after the war. The lesson culminates with students creating a commemorative currency honoring the contributions and sacrifices of Native Americans during and after World War II. Grade 11 NC Essential Standards for American History II • AH2.H.3.2 - Explain how environmental, cultural and economic factors influenced the patterns of migration and settlement within the United States since the end of Reconstruction • AH2.H.3.3 - Explain the roles of various racial and ethnic groups in settlement and expansion since Reconstruction and the consequences for those groups • AH2.H.4.1 - Analyze the political issues and conflicts that impacted the United States since Reconstruction and the compromises that resulted • AH2.H.7.1 - Explain the impact of wars on American politics since Reconstruction • AH2.H.7.3 - Explain the impact of wars on American society and culture since Reconstruction • AH2.H.8.3 - Evaluate the extent to which a variety of groups and individuals have had opportunity to attain their perception of the “American Dream” since Reconstruction Materials • Cracking the Code handout, attached (p. -

Closingin.Pdf

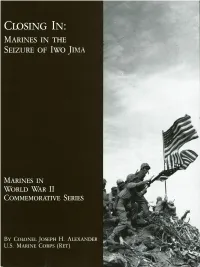

4: . —: : b Closing In: Marines in the Seizure of Iwo Jima by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret) unday, 4 March 1945,sion had finally captured Hill 382,infiltrators. The Sunday morning at- marked the end of theending its long exposure in "The Am-tacks lacked coordination, reflecting second week ofthe phitheater;' but combat efficiencythe division's collective exhaustion. U.S. invasion of Iwohad fallen to 50 percent. It wouldMost rifle companies were at half- Jima. By thispointdrop another five points by nightfall. strength. The net gain for the day, the the assault elements of the 3d, 4th,On this day the 24th Marines, sup-division reported, was "practically and 5th Marine Divisions were ex-ported by flame tanks, advanced anil." hausted,their combat efficiencytotalof 100 yards,pausingto But the battle was beginning to reduced to dangerously low levels.detonate more than a ton of explo-take its toll on the Japanese garrison The thrilling sight of the Americansives against enemy cave positions inaswell.GeneralTadamichi flag being raised by the 28th Marinesthat sector. The 23d and 25th Ma-Kuribayashi knew his 109th Division on Mount Suribachi had occurred 10rines entered the most difficult ter-had inflicted heavy casualties on the days earlier, a lifetime on "Sulphurrain yet encountered, broken groundattacking Marines, yet his own loss- Island." The landing forces of the Vthat limited visibility to only a fewes had been comparable.The Ameri- Amphibious Corps (VAC) had al-feet. can capture of the key hills in the ready sustained 13,000 casualties, in- Along the western flank, the 5thmain defense sector the day before cluding 3,000 dead. -

Flags of Our Fathers: a Novel by James Bradley with Ron Powers by Spencer Green, Staff Writer

~ ________ Issue ~ http://www.elsegundousd.com/eshs/bayeagle0607/NovembeP25FlagsO... Flags of our Fathers: A Novel by James Bradley with Ron Powers by Spencer Green, Staff Writer “There are no great men. Just great challenges which ordinary men, out of necessity, are forced by circumstances to meet.” Admiral William F. “Bull” Hawlsey's words are the theme of Flags Of Our Fathers. Flags Of Our Fathers is not a book about heroes; instead, it is an account of six ordinary men doing what they had to in order to help their brothers in arms. No doubt, you've seen the picture before: the picture of six men raising a flag over Iwo Jima during World War II. James Bradley and Ron Powers have finally told the story of the six men in this iconic image. Bradley's father, John, is one of these men, one of the flag raisers who became instant heroes once the picture got back to America. While the Marines and Navy personnel continued to fight on Iwo Jima, the image began hitting newsstands around the country. This picture instilled hope in Americans, inspiring a country that was tired of fighting. The figures in the picture became national heroes, despite the fact that half of them were killed in combat soon after the famous picture was taken. Bradley tells the reader of how his father, John "Doc" Bradley, and the two other survivors, Rene Gagnon and Ira Hayes, were forced to go around the country to raise money for the government. This was painful for the three men, as they had been forced to see many of their friends die horribly in battle, and they felt as if their dead and wounded comrades deserved the glory and fame more than them.