ELECTION DAY VOTER REGISTRATION: Simplifying the Voting Process and Increasing Voter Turnout in New York City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BRUSHES with HISTORY IMAGINATION and INNOVATION in ART EDUCATION HISTORY DATES: NOV 19–22, 2015 RECEPTION: NOV 19, 6-8PM V V V

BRUSHES WITH HISTORY IMAGINATION AND INNOVATION IN ART EDUCATION HISTORY DATES: NOV 19–22, 2015 RECEPTION: NOV 19, 6-8PM v v v WELCOME TO BRUSHES WITH HISTORY: IMAGINATION AND INNOVATION IN ART EDUCATION HISTORY (BWH) at Teachers College (TC). Our goal is to provide a forum for the presentation and discussion of ideas, issues, information, and research approaches utilized in the historical investigation of art education within local and global contexts. We will offer opportunities to engage with the rich resources in art education history at TC and beyond, explore more sophisticated approaches and methods of historical research, encourage interest in historical research, and extend the conversation on how meaning is produced in historical research trends and representations. This conference comes two decades after the last academic conference on the history of art education held at The Pennsylvania State University in 1995. TC’s legacy of “firsts” begins with the College itself and focuses on renewing this legacy through TC’s Campaign. This is the first history of art education conference taking place in the 127-year history of the College as well as that of the Program in Art & Art Education. The conference title highlights Imagination and Innovation in Art Education History. On the face of it, acts of imagination and innovation have not always been thought synonymous with our perceptions of history. Enshrined in former documents, statutes, and pronouncements of trained experts, the historical records of TC and art education history, cathedral-like, have seemed carved in stone for all time. Yet the carved gargoyles of personal histories excavated from a widening global context and told in vernaculars as old and varied as history itself challenge us with a new and more complex story that is yet in the making, providing a platform to sustain a vibrant culture of innovation and groundbreaking scholarship at TC. -

Classroom Laptops Re-Examined

The Mosaic A PUBLICATION OF THE HUGH N. BOYD JOURNALISM DIVERSITY WORKSHOP AT MONMOUTH UNIVERSITY IN WEST LONG BRANCH, NJ JULY 27, 2007 Classroom How moved are we? laptops re-examined BY SHARON KIM STAFF WRITER In the fall of 2006, school districts, such as Bergen County Academies in Hackensack, installed laptops in classrooms to facilitate learning and to motivate students. At first, this seemed like a brilliant idea to school administrations: paperless classrooms, instant information and the convenience of cut-and-paste. Brian Kwee, a senior at Bergen County Academies, said, “I think that laptops are useful tools in our school. With these laptops, students can save time with their research.” Because of these advantages, the Pascack Valley High School District launched “1:1 Laptop eLearning Initiative,” a program that gave faculty and students wireless laptops. This four-year project was implemented Marta Paczkowska/Staff Photographer in 2004 to change the way teachers teach A handkerchief is draped over a concert goer’s head at the Live Earth concenrt held at Giants Stadium in East Rutherford, NJ on July 7. and students learn. The administration believed that with access to any information any time, students were better prepared for their education. Concert inspires environmental change According to a presentation by Paul Cohen, assistant superintendent at the BY MARTA PACZKOWSKA namely by making everyday eco-friendly asked if he signed the pledge after seeing Pascack Valley Regional High School, STAFF WRITER choices and signing a seven-point pledge, the concert at Giants Stadium, Jeff Laux, to the school’s Board of Education in devised by Gore to support “green” a freshman at the College of New Jersey, February 2004, studies showed technology S.O.S. -

A Case Study of the Naz Foundation's Campaign to Decriminalize Homosexuality in India Preston G

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Capstone Collection SIT Graduate Institute Winter 12-4-2017 Lessons for Legalizing Love: A Case Study of the Naz Foundation's Campaign to Decriminalize Homosexuality in India Preston G. Johnson SIT Graduate Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/capstones Part of the Civic and Community Engagement Commons, Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, History of Gender Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, Law and Gender Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legislation Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, Litigation Commons, Policy Design, Analysis, and Evaluation Commons, Political Science Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, Sexuality and the Law Commons, Social Policy Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Preston G., "Lessons for Legalizing Love: A Case Study of the Naz Foundation's Campaign to Decriminalize Homosexuality in India" (2017). Capstone Collection. 3063. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/capstones/3063 This Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Graduate Institute at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -

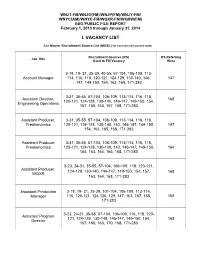

I. Vacancy List

WNJT-FM/WNJO(FM)/WNJP(FM)/WNJY-FM/ WNYC(AM)/WNYC-FM/WQXR-FM/WQXW(FM) EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT February 1, 2013 through January 31, 2014 I. VACANCY LIST See Master Recruitment Source List (MRSL) for recruitment source data Recruitment Sources (RS) RS Referring Job Title Used to Fill Vacancy Hiree 3-18, 19- 31, 35-39, 40-55, 57-104, 106-109, 113- Account Manager 114, 116, 118, 120-121, 124-129, 130-140, 146- 147 147, 149-150, 154, 163, 168, 171-283 3-31, 35-55, 57-104, 106-109, 113-114, 116, 118, Assistant Director, 168 120-121, 124-128, 130-140, 146-147, 149-150, 154, Engineering Operations 157, 160, 163, 167, 168, 171-283 Assistant Producer, 3-31, 35-55, 57-104, 106-109, 113-114, 116, 118, Freakonomics 120-121, 124-128, 130-140, 142, 146-147, 149-150, 147 154, 163, 165, 168, 171-283 Assistant Producer 3-31, 35-55, 57-104, 106-109, 113-114, 116, 118, Freakonomics 120-121, 124-128, 130-140, 142, 146-147, 149-150, 164 154, 163, 164, 165, 168, 171-283 3-23, 24-31, 35-55, 57-104, 106-109, 118, 120-121, Assistant Producer, 124-129, 130-140, 146-147, 149-150, 154, 157, 168 WQXR 163, 164, 168, 171-283 Assistant Production 3-18, 19- 31, 35-39, 101-104, 106-108, 113-114, Manager 116, 120-121, 124-126, 129, 147, 163, 167, 168, 168 171-283 3-23, 24-31, 35-55, 57-104, 106-109, 116, 118, 120- Assistant Program 121, 124-129, 130-140, 146-147, 149-150, 154, 168 Director 157, 160, 163, 170, 168, 171-283 WNJT-FM/WNJO(FM)/WNJP(FM)/WNJY-FM/ WNYC(AM)/WNYC-FM/WQXR-FM/WQXW(FM) EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT February 1, 2013 through January 31, 2014 Recruitment Sources -

Websites for Math

E-BOOK of ~ Makes students “ACTIVE” learners! ~ By Joan M. Azarva, Ms.ED http://www.ConquerCollegewithLD.com (215) 620-2112 Updated June 2010 Math Websites Red indicates: Useful for instructors, parents, and possibly students ANY MATH COURSE http://www.khanacademy.org/ GREAT VIDEOS – Explain concepts in easy-to-understand fashion for almost any math course. http://www.mathway.com/ MATH SOLVER - Mathway provides students with the tools they need to solve their math problems. With tens of millions of problems already solved, Mathway is the #1 online problem solving resource available for students, parents, and teachers. http://mathtv.com/ VIDEOS by topic or textbook http://www.brightstorm.com/math EXCELLENT MATH VIDEOS - Great teachers explaining sample problems on video – algebra to calculus. http://www.explorelearning.com/index.cfm?method=cCorp.dspLearnMore ExploreLearning.com offers the world's largest library of interactive online simulations for math and science education in grades 3-12. We call these simulations Gizmos. Free 30-day trial for all 450 Gizmos – EXCELLENT SITE FOR GRADES 3 - 12 http://mtsu32.mtsu.edu:11064/skill.html MATH STUDY SKILLS INVENTORY – find out if your study habits are effective. http://themathworksheetsite.com/numline.html NUMBER LINE GENERATOR – enter beginning and end points, along with desired intervals, and number line is created http://nces.ed.gov/nceskids/graphing/ CREATE A GRAPH – Enter your own data (area, pie, line or bar) http://www.onlineconversion.com/ CONVERT JUST ABOUT ANY UNIT TO ANY OTHER - over 5,000 units, and 50,000 conversions. http://cs.jsu.edu/mcis/faculty/leathrum/Mathlets/ INTERACTIVE - Collection of JAVA applets for precalculus, calculus, graphing, three-dimensional graphing http://www.printfreegraphpaper.com/ PRINT GRAPH PAPER to keep columns straight with math problems. -

Asian Columbia Alumni Association 20Th Anniversary Gala

CHESTER LEE AWARDEES PERFORMANCE '70SEAS, '74BUS, RE- ACAA HERITAGE CU HARMONY FLECTS ON THE HIS- COLUMBIA IMPACT INDIE DANCE RISING LION TORY OF ACAA Asian Columbia Alumni Association 20th Anniversary Gala Dear Esteemed Alumni, Friends, Supporters, and Administra- Mission Statement tors, Asian Columbia Alumni Association On April 30th, Asian Columbia Alumni Association (ACAA) is a non-profit organization bringing celebrated its 20th anniversary in Low Memorial Library Rotun- together the global Asian Columbia da with more than 200 attendees, reflecting on its legendary past community to collectively support, and re-energizing the next twenty years. We introduced keynote develop and promote common in- terests and experiences. speakers Victor Cha and Sreenath Sreenivasan, awarded alumni ACAA Gala Newsletter 2016 with great achievements, and enjoyed vibrant student performances. Here are some high- lights of the gala from ACAA members: This is a milestone we achieved, and we have a lot more to look forward to in the next 20 years. It is the A teamwork with a common vision. It is all about you, supporters, donors, members in the ACAA family. Let’s march together for the next 20 years to build a global Asian Columbia Alumni community. —Yiting Shen, ’01SEAS, ’02SEAS The gala is like a button that we pressed to reset the range of service that ACAA could deliv- er to its member and reset the outlook of the next 20 years. I am glad and pleased to be part of this process of building a truly “global” Asian Columbia Community, and I hope that you could join us, and become part of the process, too. -

Newsroom Training: Where's the Investment?

1 . 1 . 1 . 1 . 1 . 1 . 1 . 2 . NEWSROOM TRAINING: WHERE’S THE INVESTMENT? . 3 . 3 . 3 . 3 . 3 . 3 . 3 . DILBERT reprinted with permission of United Feature Syndicate Inc. Newsroom Training: Where’s the Investment? is a Princeton Survey Public Radio News Directors Inc. Research Associates project, cosponsored by the Council of Presi- Radio-Television News Directors Association dents of National Journalism Organizations and the John S. and Radio-Television News Directors Foundation Table of Contents James L. Knight Foundation. Religion Newswriters Association Society for News Design The Council of Presidents – Ted Gest, chair; Melinda Voss, vice Society of American Business Editors and Writers Introduction . 4 chair – presented the survey in April 2002 at the annual conference Society of Environmental Journalists of the American Society of Newspaper Editors in Washington, D.C. Society of Professional Journalists The findings were simultaneously released at the Radio-Television South Asian Journalists Association Newsroom Training: News Directors convention in Las Vegas. Where’s the Investment? . 8 Newsroom Training: Where’s the Investment? was funded by the John The council includes representatives from the following groups: S. and James L. Knight Foundation. It was written by consulting editor Beverly Kees, University of Maryland Knight Chair in Journal- American Association of Sunday and Feature Editors ism Haynes Johnson, and the staff of Princeton Survey Research Twelve Key Survey Findings. 19 American Copy Editors Society Associates; edited by Eric Newton and designed by Jacques Auger American Society of Magazine Editors Design Associates, Miami Beach, Fla. Special thanks to Diane st American Society of Newspaper Editors McFarlin, Caesar Andrews, Ted Gest, Larry Hugick, John Bare, Yves News and the 21 Asian American Journalists Association Colon, Larry Meyer, Caroline Wingate, Tanya Nieto and Mimi Century: A Winding Road Associated Press Managing Editors Chacin. -

Journalism and Mass Communication Schools

Alabama • Alabama, University of mail: Box 870172, Tuscaloosa, AL 35487-0172. street: Reese Phifer Hall, 901 University Blvd., Tuscaloosa, AL 35487; Tel: (205) 348-4787, FAX: (205) 348-3836; Email: [email protected], College of Communication and Information Sciences, 1927. ACES, SPJ, NABJ, NPPA. Loy Singleton, Dean. FACULTY: Profs.: Elizabeth Aversa, Beth S. Bennett (chair, Communication Studies), Bruce Berger (Phifer professor), Andrew Billings (Reagan chair), Kimberly Bissell (assoc. dean Research, Southern Progress prof.), Rick Bragg, Matthew Bunker (Phifer prof.), Jeremy Butler, Karen J. Cartee, William Evans, William Gonzenbach, Karla Gower (Behringer prof.), Heidi Julien (dir., School of Library and Information Studies), Steven Miller, Yorgo Pasadeos, Joseph Phelps (chair, Advertising and Public Relations), Pamela Doyle Tran, Danny Wallace (EBSCO chair), Shuhua Zhou (assoc. dean, Graduate Studies); Assoc. Profs.: Jason Edward Black (asst. dean, Undergraduate Student Services), Gordon Coleman, Caryl Cooper (asst. dean, Undergraduate Studies), George Daniels, Anne Edwards, Janis Edwards, Anna Embree, Jennifer Greer (chair, Journalism), William Glenn Griffin, Lance Kinney, Margot Lamme, Wilson Lowrey, Steven MacCall, Carol Bishop Mills, Jeff Weddle, Glenda Williams (chair, Telecommunication and Film); Asst. Profs.: Dan Albertson, Meredith Bagley, Jane Baker, Laurie Bonnici, Robin Boylorn, Jennifer Campbell-Meier, Alexa Chilcutt, Kristen Heflin, Suzanne Horsley, Hyoungkoo Khang, Eyun-Jung Ki, Doohwang Lee, Regina Lewis, Mary Meares, Jamie Naidoo (Foster-EBSCO prof.), Matthew Payne, Rachel Raimist, Robert Riter, Chris Roberts, Adam Schwartz, Lu Tang, Kristen Warner; Lecturers: Chip Brantley, Dwight Cammeron, Andrew Grace, David Grewe; Instrs.: Angela Billings, Dianne Bragg, Michael Bruce, Chandra Clark, Nicholas Corrao, Treva Dean, Meredith Cummings, Susan Daria, Naomi Gold, Teri Henley, Robert Imbody, Michael Little, Daniel Meissner, Jim Oakley (placement dir.), Tracy Sims, Charles Womelsdorf. -

AAJA Handbook

AAJAHandbookFront 7/14/00 7:19 PM Page 2 in cooperation with south asian journalists SAJA association with generous support from Copyright 2000, Asian American Journalists Association. For additional copies of the Handbook or rights and reprint information, please contact us at: AAJA, 1182 Market Street, Suite 320, San Francisco, CA 94102; (415) 346-2051. [email protected] http://www.aaja.org/ We gratefully acknowledge the generous support of Knight-Ridder, Inc. in funding this project. AAJAfinalhandbook2 7/14/00 7:18 PM Page 1 ALL-AMERICAN: How to Cover Asian America AAJAfinalhandbook2 7/14/00 7:18 PM Page 2 Acknowledgments Without his deft touch and countless hours at the comput- er, it would have never been completed. The Asian American Journalists Association was AAJA also thanks Sreenath Sreenivasan of Columbia founded in 1981 by a group of Los Angeles–based profes- University and the South Asian Journalists Association, sionals with three distinct, but intersecting, goals: our brothers and sisters in the good fight, and Jeff Yang and his staff at aMedia, who copyedited and produced this •To recruit and train a new generation of Asian volume, particularly lead Handbook designer Setiaputra Americans in journalism, Lukas. •To promote fair and accurate coverage of Asians in We also thank Ken Moritsugu of Knight-Ridder America and highlight the community’s diversity, and Newspapers’ Washington Bureau, who initiated this project •To prepare Asian American journalists for leadership and when he was president of AAJA’s New York chapter; the management roles in the country’s newsrooms. energetic members of AAJA-New York, our largest chap- ter and hosts for the 2000 convention; Jon Funabiki of This revised handbook continues AAJA’s legacy of lead- the Ford Foundation, whose wise counsel is priceless; and ership in the journalism industry and the Asian American Francisco Mattos, our designer in San Francisco, who community. -

September 29, 2006 (PDF, 2.2MB)

FACULTY Q & A AT ISSUE SCRAPBOOK June Cross’ The fad for memoirs Nobel laureates and double life | 4 and blogs | 5 world leaders | 8 VOL. 32, NO. 2 NEWS AND IDEAS FOR THE COLUMBIA COMMUNITY SEPTEMBER 29, 2006 EVENT SERIES ALUMNI AFFAIRS WLF Opens COLUMBIA with Stiglitz LAUNCHES MAJOR Forum FUNDRAISING By Mary-Lea Cox CAMPAIGN he Nobel Prize-winning By Marcus Tonti economist Joseph Stiglitz remembers entering a oday Columbia University bookstore in Taiwan some launched a $4 billion T20 years ago and wondering how fundraising campaign in he would feel if he saw a pirated global style, with simulta- copy of his latest book on the Tneous events in New York, London shelves. Although he knew all the and Hong Kong. arguments in favor of protecting The campaign seeks to add $1.6 intellectual property, he also knew billion to Columbia’s endowment, the costs to the public good of with special emphasis on financial restricting the transfer of ideas. aid and faculty support across the He decided that on balance he campuses. Also sought is $1 billion would prefer to see a pirated ver- for new and renovated facilities and sion of his book—and was pleased $1.4 billion for spendable support of when he indeed found one. programs throughout the University. The former World Bank chief Increasing alumni engagement is economist, who is now a University another explicit campaign goal. Professor at Columbia, delivered this President Bollinger, joined by anecdote to a packed audience gath- several University trustees and ered in Roone Arledge Auditorium for the start of this year’s World $425m earmarked for Leaders Forum, on Sept. -

2011 Annual Report

2 011 ANNUAL REPORT breakthrough 2011 ANNUAL REPORT 01 // MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT PG 2-3 02 // METHODOLOGY PG 4-5 03 // BELL BAJAO/RING THE BELL GLOBAL PG 6-9 04 // BREAKTHROUGH RIGHTS ADVOCATES PG 10-13 05 // AMERICA 2049 PG 14-15 06 // RESTORE FAIRNESS PG 16-17 07 // BREAKTHROUGH IN THE GLOBAL PRESS PG 18 08 // GLOBAL PRESENTATIONS PG 19 09 // SPECIAL EVENTS PG 20 10 // FINANCIAL REPORT PG 21 11 // BOARD & STAFF PG 22-23 12 // SUPPORTERS PG 24-27 13 // GET INVOLVED PG 28 Message From The President MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT. “The only way to ensure that all of us can live with dignity is to make sure that equality and respect live and thrive in our homes, our families, and our communities. Please join us in bringing human rights home.” - Mallika Dutt, TEDx 4 Breakthrough // Annual Report 2011 Human rights can come alive with the Through all of our multimedia tools and in- words and actions of just one person. One depth leadership trainings, we say, “Human person like Mansimran, an all-American — rights start with you. And each year, more and Sikh-American — teen with immense and more young people worldwide stand empathy for people who see his turban and up and say, “Human rights start with me.” I call him a “terrorist.” How does Mansimran am humbled and honored to see their bold, respond? “Sit down,” he’ll say. “I’ll tell you brave actions unfold and multiply. And I am who I am.” Or one person like Sarita. Through so grateful for the partnership and support of Breakthrough’s human rights training, she all who share our vision. -

American Backlash: Terrorist Bring War Home in More Ways Than

american backlash terrorists bring war home in more ways than one a special report by south asian american leaders of tomorrow american backlash terrorists bring war home in more ways than one board of directors Jeet Bindra, Chair President, Chevron Pipe Line Co. Indira K. Ahluwalia, Vice Chair Manager - Marketing, International Business & Technical Consultants Deepa Iyer, Secretary Civil Rights Attorney Debasish Mishra, Treasurer Vice President, Masala, Inc. project leader Ankur Agrawal - Engineer, Advanced Micro Devices Debasish Mishra Shom Bhattacharya - Managing Director, JP Morgan Securities editing Jay Chadhuri - Sp. Asst. to the Attorney General, State of N. Carolina Deepa Iyer Probir Mehta - JD Candidate, George Washington University research Meena Morey Chandra - Civil Rights Kiran Chaudhri, Kulmeet Dang, Poonam Desai, Ankur Doshi, Attorney Parvinder Kang,Debasish Mishra, Sunny Rehman, Fred de Sam Lazaro - Correspondent, The Newshour with Jim Lehrer Vivek Sankaran Sreenath Sreenivasan - Assoc. Professor, photo credit Columbia University Dylan Martinez (Reuters), Dita Alangkara (AP), Mark Lenniham board of trustees (AP), Carlos Osorio (AP), Fred Greaves (AP), Derek Ruttan Prakash Agarwal - CEO, NeoMagic Corp. (AP), Boudicon One (AP), Charles Bennett (AP), Jayant S. Kalotra - CEO, Intl. Business & Adrees Latif (Reuters), Kenneth Lambert (AP) Technical Consultants, Inc. Rakesh Kaul - CEO, Hanover Direct special thanks Gopal Khanna - CEO, Intl. Tecnical Consultants Deepa Iyer for assisting with recommendations Kishore Kripalani -