1 Why the Wizards of Armageddon Ran Into an Intellectual Dead-End

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Albert Wohlstetter's Legacy: the Neo-Cons, Not Carter, Killed

SPECIAL REPORT: NUCLEAR SABOTAGE ALBERT WOHLSTETTER’S LEGACY Wohlstetter was even stranger than the “Dr. Strangelove” depicted in the 1964 movie of that name. An early draft of the film was titled “The Delicate Balance of Terror,” the same title as Wohlstetter’s best-known unclassified work. Here, a still from the film. tives—Paul Wolfowitz, Richard Perle, and Zalmay Khalilzad, to name a few. In Wohlstetter’s circle of influence were also Ahmed Chalabi (whom Wohlstetter championed), Sen. Henry “Scoop” Jackson (D-Wash.), Sen. Robert Dole (R- Kan.), and Margaret Thatcher. Wohlstetter himself was a follower of Bertrand Russell, not only in mathematics, but in world outlook. The pseudo-peacenik Russell had called for a preemptive strike against the Soviet Union, after World War II and before the Soviets developed the bomb, as a prelude to his plan for bully- ing nations into a one-world government. Russell, a raving Malthusian, opposed economic development, especially in the Third World. Admirer Jude Wanniski wrote of Wohlstetter in an obituary, “[I]t is no exaggeration, I think, to say that Wohlstetter was the most influential unknown man in the world for the past half century, and easily in the top ten in importance of all men.” “Albert’s decisions were not automat- ically made official policy at the White House,” Wanniski wrote, “but Albert’s The Neo-Cons, Not Carter, genius and his following were such in the places where it counted in the Establishment that if his views were Killed Nuclear Energy resisted for more than a few months, it -

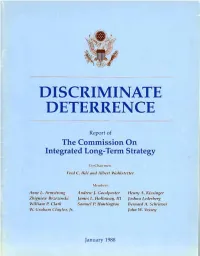

Discriminate Deterrence

DISCRIMINATE DETERRENCE Report of The Commission On Integrated Long-Term Strategy Co -C. I lairmea: Fred C. lkle and Albert Wohlstetter Moither, Anne L. Annsinmg Andrew l. Goodraster flenry /1 Kissinger Zbign ei Brzezinski fames L. Holloway, Ur Joshua Lederberg William P. Clark Samuel P. Huntington Bernard A. Schriever tV. Graham Ciaytor, John W. Vessey January 1988 COMMISSION ON INTEGRATED LONG-TERM STRATEGY January 11. 1988 MEMORANDUM FOR: THE SECRETARY OF DEFENSE THE ASSISTANT TO THE PRESIDENT FOR NATIONAL SECURITY AFFAIRS We are pleased to present this final report of Our Commission. Pursuant to your initial mandate, the report proposes adjustments to US. military strategy in view of a changing security environment in the decades ahead. Over the last fifteen months the Commission has received valuable counsel from members of Congress, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Service Chiefs. and the Presdent's Science Advisor, Members of the National Security Council Staff, numerous professionals in the Department of Defense and the Central Intelligence Agency, and a broad range of specialists outside the government provided unstinting support. We are also indebted to the Commission's hardworking staff. The Commission was supported generously by several specialized study groups that closely analyzed a number of issues, among them: the security environment for the next twenty years, the role of advanced technology in military systems, interactions between offensive and defensive systems on the periphery of the Soviet Union, and the U.S, posture in regional conflicts around the world. Within the next few months, these study groups will publish detailed findings of their own. -

Conquest of Armageddon

CONQUEST OF ARMAGEDDON A Warhammer 40K novel by Jonathan Green THE BLACK TEMPLARS are one of the most deter- mined Chapters of Space Marines – refusing to take a step backwards, no matter what the conse- quences. When one of their units goes missing in the ork infested jungles of Armageddon, an elite squad is sent to investigate. Their mission is fur- ther complicated by the presence of a key Imperial officer who has crash-landed behind enemy lines. Hunted by both the savage orks and the corrupted Chaos Space Marines, the Black Templars must call upon every ounce of their faith and firepower if they are to survive and rescue their lost bat- tle-brothers. Jonathan Green has been a freelance writer for the last thir- teen years. He has written Fighting Fantasy and Sonic the Hedgehog gamebooks. His work for the Black Library, to date, includes a string of short stories for Inferno! magazine and six novels. Jonathan works as a full-time teacher in West London. Conquest of Armageddon can be purchased in all better bookstores, Games Workshop and other hobby stores, or direct from this website and GW mail order. Price £6.99 (UK) / $7.99 (US) Bookshops: Distributed in the UK by Hodder. Distributed in the US by Simon & Schuster Books. Games & hobby stores: Distributed in UK and US by Games Workshop. UK mail order: 0115-91 40 000 US mail order: 1-800-394-GAME Online: Buy direct care of Games Workshop’s web store by going to www.blacklibrary.com/store or www.games-workshop.com PUBLISHED BY THE BLACK LIBRARY TM Games Workshop, Willow Road, Nottingham, NG7 2WS, UK Copyright © 2005 Games Workshop Ltd. -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

Copyright by Paul Harold Rubinson 2008

Copyright by Paul Harold Rubinson 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Paul Harold Rubinson certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Containing Science: The U.S. National Security State and Scientists’ Challenge to Nuclear Weapons during the Cold War Committee: —————————————————— Mark A. Lawrence, Supervisor —————————————————— Francis J. Gavin —————————————————— Bruce J. Hunt —————————————————— David M. Oshinsky —————————————————— Michael B. Stoff Containing Science: The U.S. National Security State and Scientists’ Challenge to Nuclear Weapons during the Cold War by Paul Harold Rubinson, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Acknowledgements Thanks first and foremost to Mark Lawrence for his guidance, support, and enthusiasm throughout this project. It would be impossible to overstate how essential his insight and mentoring have been to this dissertation and my career in general. Just as important has been his camaraderie, which made the researching and writing of this dissertation infinitely more rewarding. Thanks as well to Bruce Hunt for his support. Especially helpful was his incisive feedback, which both encouraged me to think through my ideas more thoroughly, and reined me in when my writing overshot my argument. I offer my sincerest gratitude to the Smith Richardson Foundation and Yale University International Security Studies for the Predoctoral Fellowship that allowed me to do the bulk of the writing of this dissertation. Thanks also to the Brady-Johnson Program in Grand Strategy at Yale University, and John Gaddis and the incomparable Ann Carter-Drier at ISS. -

The BG News April 15, 1999

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 4-15-1999 The BG News April 15, 1999 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News April 15, 1999" (1999). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6484. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6484 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. ■" * he BG News Women rally to 'take back the night' sexual assault. istration vivors, they will be able to relate her family. By WENDY SUTO Celesta Haras/ti, a resident of buildings, rain to parts of her story, Kissinger "The more I tell my story, the The BG News BG and a W4W member, said the or shine. The said. less shame and guilt I feel," Kissinger said. "For my situa- Women (and some men) will rally is about issues that are con- keynote "When I decided to disclose tion, I'm glad I didn't tell my take to the streets tonight, pro- sidered taboo by society, such as speaker, my sexual abuse to my family, I parents right away because I claiming a public statement in an rape and incest. She has attended Kendel came out of the closet complete- think it would have been a worse attempt to "Take Back the Night" several TBTN marches at the Kissinger, a ly," Kissinger said. -

The Vulnerabilities of Developed States to Economic Cyber Warfare

Working Paper The Vulnerabilities of Developed States to Economic Cyber Warfare Paul Cornish Head, International Security Programme and Carrington Professor of International Security, Chatham House June 2011 The views expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of Chatham House, its staff, associates or Council. Chatham House is independent and owes no allegiance to any government or to any political body. It does not take institutional positions on policy issues. This document is issued on the understanding that if any extract is used, the author and Chatham House should be credited, preferably with the date of the publication. Working Paper: The Vulnerabilities of Developed States to Economic Cyber Warfare INTRODUCTION The central features of the ‘cybered’ world of the early 21st century are the interconnectedness of global communications, information and economic infrastructures and the dependence upon those infrastructures in order to govern, to do business or simply to live. There are a number of observations to be made of this world. First, it is still evolving. Economically developed societies are becoming ever more closely connected within themselves and with other, technologically advanced societies, and all are becoming increasingly dependent upon the rapid and reliable transmission of ideas, information and data. Second, where interconnectedness and dependency are not managed and mitigated by some form of security procedure, reversionary mode or redundancy system, then the result can only be a complex and vitally important communications system which is nevertheless vulnerable to information theft, financial electronic crime, malicious attack or infrastructure breakdown. -

Foreign Policy Analysis

FOREIGN POLICY ANALYSIS (listed in catalogue as Theoretical Explanations of Foreign Policy) Pol Sci 530 Jack S. Levy Rutgers University Spring 2014 Hickman 304 848/932-1073 [email protected] http://fas-polisci.rutgers.edu/levy/ Office Hours: after class and by appointment This seminar focuses on how states formulate and implement their foreign policies. Foreign Policy Analysis is a well-defined subfield within the International Relations field, with its own sections in the International Studies Association and American Political Science Association (Foreign Policy Analysis and Foreign Policy, respectively). Our orientation in this course is more theoretical and process-oriented than substantive or interpretive. We focus on policy inputs and the decision-making process rather than on policy outputs. An important assumption underlying this course is that the processes through which foreign policy is made have a considerable impact on the substantive content of policy. We follow a loose a levels-of-analysis framework to organize our survey of the theoretical literature on foreign policy. We examine rational state actor, bureaucratic/ organizational, institutional, societal, and psychological models. We look at the government decision-makers, organizations, political parties, private interests, social groups, and mass publics that have an impact on foreign policy. We analyze the various constraints within which each of these sets of actors must operate, the nature of their interactions with each other and with the society as a whole, and the processes and mechanisms through which they resolve their differences and formulate policy. Although most (but not all) of our reading is written by Americans and although much of it deals primarily with American foreign policy, most of these conceptual frameworks are much more general and not restricted to the United States. -

Theories of International Relations* Ole R. Holsti

Theories of International Relations* Ole R. Holsti Universities and professional associations usually are organized in ways that tend to separate scholars in adjoining disciplines and perhaps even to promote stereotypes of each other and their scholarly endeavors. The seemingly natural areas of scholarly convergence between diplomatic historians and political scientists who focus on international relations have been underexploited, but there are also some signs that this may be changing. These include recent essays suggesting ways in which the two disciplines can contribute to each other; a number of prizewinning dissertations, later turned into books, by political scientists that effectively combine political science theories and historical materials; collaborative efforts among scholars in the two disciplines; interdisciplinary journals such as International Security that provide an outlet for historians and political scientists with common interests; and creation of a new section, “International History and Politics,” within the American Political Science Association.1 *The author has greatly benefited from helpful comments on earlier versions of this essay by Peter Feaver, Alexander George, Joseph Grieco, Michael Hogan, Kal Holsti, Bob Keohane, Timothy Lomperis, Roy Melbourne, James Rosenau, and Andrew Scott, and also from reading 1 K. J. Holsti, The Dividing Discipline: Hegemony and Diversity in International Theory (London, 1985). This essay is an effort to contribute further to an exchange of ideas between the two disciplines by describing some of the theories, approaches, and "models" political scientists have used in their research on international relations during recent decades. A brief essay cannot do justice to the entire range of theoretical approaches that may be found in the current literature, but perhaps those described here, when combined with citations of some representative works, will provide diplomatic historians with a useful, if sketchy, map showing some of the more prominent landmarks in a neighboring discipline. -

What We Don't Know Can Help

Running head: ELICITING KNOWLEDGE FOR WORK WITH INTRACTABLE CONFLICTS What We Don’t Know Can Help Us: Eliciting Out-of-Discipline Knowledge for Work with Intractable Conflicts Jennifer S. Goldman Columbia University Peter T. Coleman Columbia University Correspondence concerning this article should be sent to Jennifer S. Goldman or Peter T. Coleman at the following address: Box 53, Teachers College, Columbia University, 525 West 120th St., New York, NY 10027, Phone: (212) 678-3402, Fax: (212) 678-4048. Electronic mail may be sent to Jennifer S. Goldman at [email protected] or to Peter T. Coleman at [email protected] Eliciting Knowledge for Work with Intractable Conflicts 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………….3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………..9 Method…………………………………………………………………………………….9 Findings……………………...…………………………………………………………..10 Methodological Learnings / Recommendations………………………………………....49 References………………………………………………………………………………..52 Appendices……………………………………………………………………………….53 Eliciting Knowledge for Work with Intractable Conflicts 3 What We Don’t Know Can Help Us: Eliciting Out-of-Discipline Knowledge for Work with Intractable Conflicts Jennifer Goldman Columbia University & Peter T. Coleman Columbia University Executive Summary The current state of theory, research, and practice on protracted, intractable conflict is robust but limited; although much progress has been made, our understanding is bounded by discipline, culture, role-in-conflict (expert versus disputant), and social class. This pilot project, funded through a mini-grant from the Intractable Conflict Knowledge Base (ICKB), elicited alternative ways-of-knowing and engaging with the phenomenon of intractable social conflict that are typically excluded from the dominant discourse in this area. A professionally and culturally diverse group of scholar- practitioners were identified through the ICKB network as potential participants, and nine (9) pilot interviews were conducted for this study. -

The Military Guide to Armageddon • D

The Military Guide to Armageddon • D. Giamonna, T. Anderson Chosen Books, a division of Baker Publishing Group © 2021 used by permission BATTLE- TESTED STRATEGIES TO PREPARE YOUR LIFE AND SOUL FOR THE END TIMES COL. DAVID J. GIAMMONA AND TROY ANDERSON G The Military Guide to Armageddon • D. Giamonna, T. Anderson Chosen Books, a division of Baker Publishing Group © 2021 used by permission _Giammona_MilitaryGuide_ET_bb.indd 3 10/1/20 8:02 AM 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 © 2021 by David J. Giammona and Troy Anderson Published by Chosen Books 11400 Hampshire Avenue South Bloomington, Minnesota 55438 www.chosenbooks.com Chosen Books is a division of Baker Publishing Group, Grand Rapids, Michigan Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means— for example, electronic, photocopy, recording— without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Giammona, David J., author. | Anderson, Troy (Journalist), author. Title: The military guide to Armageddon: battle-tested strategies to prepare your life and soul for the end times / Col. David J. Giammona and Troy Anderson. Description: Minneapolis, Minnesota: Chosen Books, a division of Baker Publishing Group, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: LCCN 2020038021 | ISBN 9780800761943 (paperback) | ISBN 9780800762261 (casebound) | ISBN 9781493430086 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Spiritual warfare. | End of the world. | Armageddon. Classification: LCC BV4509.5 .G466 2021 | DDC 236/.9—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020038021 Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are from THE HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®, NIV® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.® Used by permission. -

Key Scriptures: Revelation 19:1-21 Ezekiel 38 & 39 Joel 2:1-11

God's Master Plan In Prophecy Lesson 13 – The Battle of Armageddon & 2nd Coming of Jesus Christ Key Scriptures: Revelation 19:1-21 Ezekiel 38 & 39 Joel 2:1-11 Zechariah 12-14 Introduction Rev 19:1 After these things I heard something like a loud voice of a great multitude in heaven, saying, "Hallelujah! Salvation and glory and power belong to our God; While the Wrath of God is being poured out, there was the voice of "a great multitude in heaven" praising God! This is the redeemed church which has missed the Wrath of God and was taken out of Great Tribulation. While the earth is experiencing the judgment of God without mercy, we are experiencing His goodness without judgment! Rev 19:2-3 BECAUSE HIS JUDGMENTS ARE TRUE AND RIGHTEOUS; for He has judged the great harlot who was corrupting the earth with her immorality, and HE HAS AVENGED THE BLOOD OF HIS BOND-SERVANTS ON HER." 3 And a second time they said, "Hallelujah! HER SMOKE RISES UP FOREVER AND EVER." From what is being said in these verse, it is obvious that the church will be fully aware of what is happening upon the earth during this time, yet because we are no longer viewing earth's events through the eyes of mortal flesh, we will understand that God is righteous and true in His judgments. To modern minds it may seem strange to worship and say, “hallelujah” over the fact that God is pouring out judgment, but that is because we see imperfectly now.