Roman Lancaster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PONTIFICAL LAW of the ROMAN REPUBLIC by MICHAEL

THE PONTIFICAL LAW OF THE ROMAN REPUBLIC by MICHAEL JOSEPH JOHNSON A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Classics written under the direct of T. Corey Brennan and approved by ____________________________ ____________________________ ____________________________ ____________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2007 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Pontifical Law of the Roman Republic by MICHAEL JOSEPH JOHNSON Dissertation Director: T. Corey Brennan This dissertation investigates the guiding principle of arguably the most important religious authority in ancient Rome, the pontifical college. Chapter One introduces the subject and discusses the hypothesis the dissertation will advance. Chapter Two examines the place of the college within Roman law and religion, giving particular attention to disproving several widely held notions about the relationship of the pontifical law to the civil and sacral law. Chapter Three offers the first detailed examination of the duties of the pontifical college as a collective body. I spend the bulk of the chapter analyzing two of the three collegiate duties I identify: the issuing of documents known as decrees and responses and the supervision of the Vestal Virgins. I analyze all decrees and responses from the point of view their content, treating first those that concern dedications, then those on the calendar, and finally those on vows. In doing so my goal is to understand the reasoning behind the decree and the major theological doctrines underpinning it. In documenting the pontifical supervision of Vestal Virgins I focus on the college's actions towards a Vestal accused of losing her chastity. -

Romans in Cumbria

View across the Solway from Bowness-on-Solway. Cumbria Photo Hadrian’s Wall Country boasts a spectacular ROMANS IN CUMBRIA coastline, stunning rolling countryside, vibrant cities and towns and a wealth of Roman forts, HADRIAN’S WALL AND THE museums and visitor attractions. COASTAL DEFENCES The sites detailed in this booklet are open to the public and are a great way to explore Hadrian’s Wall and the coastal frontier in Cumbria, and to learn how the arrival of the Romans changed life in this part of the Empire forever. Many sites are accessible by public transport, cycleways and footpaths making it the perfect place for an eco-tourism break. For places to stay, downloadable walks and cycle routes, or to find food fit for an Emperor go to: www.visithadrianswall.co.uk If you have enjoyed your visit to Hadrian’s Wall Country and want further information or would like to contribute towards the upkeep of this spectacular landscape, you can make a donation or become a ‘Friend of Hadrian’s Wall’. Go to www.visithadrianswall.co.uk for more information or text WALL22 £2/£5/£10 to 70070 e.g. WALL22 £5 to make a one-off donation. Published with support from DEFRA and RDPE. Information correct at time Produced by Anna Gray (www.annagray.co.uk) of going to press (2013). Designed by Andrew Lathwell (www.lathwell.com) The European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development: Europe investing in Rural Areas visithadrianswall.co.uk Hadrian’s Wall and the Coastal Defences Hadrian’s Wall is the most important Emperor in AD 117. -

In the Eye of the Beholder

IN THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER: THE PARADOX OF THE ROMAN PERCEPTION REGARDING THE SOCIAL STATUS OF THE EUNUCH PRIEST IN IMPERIAL ROME Silvia de Wild Supervisor 1: dr. M. (Martijn) Icks Second Reader: dr. M.P. (Mathieu) de Bakker MA Classics and Ancient Civilizations (Classics) Student number: 11238100 Words: 22.603 June 25, 2020 [email protected] 2 IN THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER: THE PARADOX OF THE ROMAN PERCEPTION REGARDING THE SOCIAL STATUS OF THE EUNUCH PRIEST IN IMPERIAL ROME University of Amsterdam, Faculty of Humanities Amsterdam Centre for Ancient Studies and Archaeology (ACASA), Classics and Ancient Civilizations: Classics (MA) Silvia de Wild Schoolstraat 5 8911 BH Leeuwarden Tel.: 0616359454/ 058-8446762 [email protected]/ [email protected] Student number: 11238100 Supervisor: dr. M. (Martijn) Icks Second Reader: dr. M.P. (Mathieu) de Bakker Words: 22.603 (appendix, bibliography, citations, source texts and translations not included) June 25, 2020. I herewith declare that this thesis is an original piece of work, which was written exclusively by me. Those instances where I have derived material from other sources, I have made explicit in the text and the notes. (Leeuwarden, June 25, 2020) 3 I would like to thank dr. L.A. (Lucinda) Dirven for sharing her time and expertise on this subject. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Research question 6 Methods and overview 7 1. Introduction 9 2. The imperial (r)evolution of the cult of Cybele and Attis 16 3. Eunuch priests in the eye of an ass: a case study on the perception of the wandering priests in Apuleius’ Metamorphoses 8.24 - 9.10 30 4. -

FOB Walking Maps 2007.Qxd

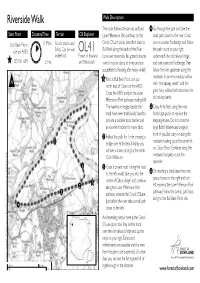

Riverside Walk Walk Description The route follows the tarmac surfaced 4 Go through the gate and take the Start Point Distance/Time Terrain OS Explorer Lune Millennium Park pathway to the small path down to the river. Cross Bull Beck Picnic 5 Miles Roads, tracks and Crook O’Lune picnic area, then back to over a wooden footbridge and follow site on A683 fields. Can be wet OL41 Bull Beck along the bank of the River the path round to your right underfoot. ‘Forest of Bowland Lune over reasonably flat grazed pastures underneath the old railway bridge, SD 541 649 2 Hrs and Ribblesdale’ (which may be damp at times and are and over a second footbridge.Then susceptible to flooding after heavy rainfall). follow the river upstream along the 1 Park at Bull Beck Picnic site, just riverbank. In summer, rosebay willow N north east of Caton on the A683. herb (the ‘railway weed’) and the Cross the A683 and join the Lune great hairy willow herb dominate the Millennium Park pathway, heading left. old railway banks. The hawthorn hedges beside the 5 Cross Artle Beck using the new track have been traditionally ‘layed’ to footbridge, put in to replace the provide a durable stock barrier and stepping-stones. Do not cross the an excellent habitat for many birds. large British Waterways bridge in 2 Follow this path for 1 mile crossing a front of you, but carry on along the 5 bridge over Artle Beck. Nearby you riverbank looking up at the windmills will see a stone carving by the artist on Caton Moor. -

Walking in Hadrian's Wall Country

Walking in Hadrian’s Wall Country Welcome to Walking in Hadrian’s Wall Country The Granary, Housesteads © Roger Clegg Contents Page An Introduction to Walking in Hadrian’s Wall Country . 3 Helping us to look after Hadrian’s Wall World Heritage Site . 4 Hadrian’s Wall Path National Trail . 6 Three walking itineraries incorporating the National Trail . 8 Walk Grade 1 Fort-to-Fort . .Easy . .10 2 Jesmond Dene – Lord Armstrong’s Back Garden . Easy . .12 3 Around the Town Walls . Easy . .14 4 Wylam to Prudhoe . Easy . .16 5 Corbridge and Aydon Castle . Moderate . .18 6 Chesters and Humshaugh . Easy . 20 7 A “barbarian” view of the Wall . Strenuous . 22 8 Once Brewed, Vindolanda and Housesteads . Strenuous . 24 9 Cawfields to Caw Gap. Moderate . 26 10 Haltwhistle Burn to Cawfields . Strenuous . 28 11 Gilsland Spa “Popping-stone”. Moderate . 30 12 Carlisle City . Easy . 32 13 Forts and Ports . Moderate . 34 14 Roman Maryport and the Smugglers Route . Easy . 36 15 Whitehaven to Moresby Roman Fort . Easy . 38 Section 4 Section 3 West of Carlisle to Whitehaven Gilsland to West of Carlisle 14 13 12 15 2 hadrians-wall.org Cuddy’s Crag © i2i Walltown Crags © Roger Coulam River Irthing Bridge © Graeme Peacock This set of walks and itineraries presents some of the best walking in Hadrian’s Wall Country. You can concentrate on the Wall itself or sample some of the hidden gems just waiting to be discovered – the choice is yours. Make a day of it by visiting some of the many historic sites and attractions along the walks and dwell awhile for refreshment at the cafés, pubs and restaurants that you will come across. -

Room II Arezzo: Finds from the Hellenistic Age

Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali SOPRINTENDENZA PER I BENI ARCHEOLOGICI DELLA TOSCANA Museo Archeologico Nazionale "Gaio Cilnio Mecenate" di Arezzo First Floor - Room I Arezzo: finds from the Archaic and Late-Archaic Period Presented in this small room is a series of objects discovered Rome. A female figure – stylistically similar but conserved in the city which date back to the Archaic and Late-Archaic separately – which can perhaps be identified with Athena, Periods. can be connected be to the group comprised of the In case 1 are the finds belonging to the votive offerings of the ploughman, yoke and oxen. The work might refer to a Fonte Veneziana (540-500 B.C.), one of the most important sanctuary context: in fact, in ancient times ploughing had a bronze complexes, together with the Falterona one, in strong sacred and ritual value. Northern Etruria. In 1869, near these springs situated just The coroplastic activity of this period in Arezzo is, instead, outside the city walls, the antiquarian Francesco Leoni found, testified by the terracotta sculptures found in Piazza S. as well as a few remains of buildings, a rich votive deposit Jacopo (walls B – C) and in via Roma (walls E – D). composed of 180 small male, female and animal bronze On Wall B is one of the most important finds in the Museum: statues, engraved stones, gold and silver rings and fragments a sima composed of three adjacent terracotta slabs decorated of Attic ceramics, which were mostly sold or dispersed with fighting scenes in high relief (480 B.C.). -

Riverside Walk OL41 Start Point Distance/Time Terrain Public Transport Key to Facilities Bull Beck Picnic Site on A683 4 Miles Roads, Tracks and Fields

OS Explorer Riverside Walk OL41 Start Point Distance/Time Terrain Public transport Key to Facilities Bull Beck Picnic site on A683 4 Miles Roads, tracks and fields. Bus Services 80, 81, 81A, 81B Post Office, Toilets, Can be wet underfoot. (Lancaster to Kirkby Pub, Shop SD 541 649 2 Hrs Lonsdale/Ingleton) GPS Waypoints (OS grid refs) N 1 SD 541 649 2 SD 538 649 3 SD 534 648 4 SD 522 647 5 SD 532 655 6 SD 539 652 5 6 1 2 3 4 © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved (100023320) (2010) © Copyright. Crown 0 Miles 0.5 Mile 0 Km 1 Km www.forestofbowland.com Riverside Walk Walk Description About This Walk The route follows the tarmac surfaced 3 GPS: SD 534 648 5 GPS: SD 532 655 Caton and Brookhouse are situated on Lune Millennium Park pathway to the Cross a private road (taking the road to Cross Artle Beck using the new the north-facing slope of the Lune Crook O’Lune picnic area, then back to the left would take you into the centre footbridge, put in to replace the Valley. The villages lie in a scenic area Bull Beck along the bank of the River of Caton village) and continue along the stepping-stones. Do not cross the large near the celebrated Crook O’Lune - Lune over reasonably flat grazed Lune Millennium Park pathway towards British Waterways bridge in front of you, painted by Turner, praised by the poets pastures (which may be damp at times the Crook O’Lune. Just before the river but carry on along the riverbank looking Thomas Gray and William and are susceptible to flooding after take a small path down to the left. -

The Minor Roman Stations of Lancashire; Also the Camps and Miscellaneous Discoveries in the County

THE MINOR ROMAN STATIONS OF LANCASHIRE; ALSO THE CAMPS AND MISCELLANEOUS DISCOVERIES IN THE COUNTY. By W. Thompson IVatkin, Esq. (Read 22nd January, 1880.) N three previous papers, I have had the pleasure of laying I before the Society all the information that former authors have bequeathed to us concerning the larger Roman stations of the county, Lancaster, Ribchester, and Manchester, with com ments upon their statements, and additional notes regarding such discoveries as have been made in recent years. In the present paper I propose to treat of the minor castra erected and held by the Roman forces during the three and a half centuries of their occupation of Lancashire and of Britain. The most noted of these is at Overburrow, only just inside the county, being about two miles south of Kirkby-Lonsdale in Westmoreland. From the fact of its distance from Ribchester, now identified with Bremetonacae, on the one side, and from the Roman station at Borrowbridge (Alio or Alionis) on the other, it is now generally admitted to be the Galacum of the Tenth Iter of Antoninus and the Galatum of Ptolemy; which seems con firmed by the name of the small river (the Lac) at whose junction with the Lone it is situated. As the site of this station is now the ground upon which a mansion stands, with large grounds attached, it has completely disappeared from above ground, though doubtless many remains are still buried beneath the surface of the lawn and gardens. We have therefore only the testimony of earlier writers to rely upon. -

Natural Environment Research Council British Geological Survey

Natural Environment Research Council British Geological Survey Onshore Geology Series TECHNICAL REPORT WA/92/16 Geology of the Littledale area 1:10 000 sheet SD56SE Part of 1:50 000 Sheet 59 (Lancaster) A BRANDON Geographical index Lancaster, Bowland Fells, Littledale Subject index Geology, Craven Basin, Carboniferous, Namurian, Arnsbergian, Quaternary Bibliographic reference Brandon. A, 1992 Geology of the Littledale area British Geological Survey Technical Report WA/92/16 «(5» NERC copyright 1992 Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 1992 CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 4 2 DINANTIAN AND NAMURIAN ROCKS OF THE WHITMOOR HYDROCARBON BOREHOLE 6 3 MILLSTONE GRIT GROUP 8 3.1 ROEBURNDALE FORMATION 8 3.1.1 Eumorphoceras ferrimontanum Marine Band 9 3.1.2 Siltstones and mudstones above the Eumorphoceras ferrimontanum Marine Band 10 3.1.3 "sa/sl" below the Close Hill Siltstone 11 3.1.4 Close Hill Siltstone Member 12 3.1.5 "sa/sl" and mudstones above the Close Hill Siltstone 13 3.1.6 Sapling Clough Sandstone Member 14 3.1.7 Eumorphoceras yatesae Marine Band and overlying beds 15 3.2 WARD'S STONE SANDSTONE FORMATION 17 3.3 CATON SHALE FORMATION 18 3.4 CLAUGHTON FORMATION 21 3.4.1 "Claughton Flags" 21 3.4.2 "Nottage Crag Grit" 22 • i A ~ 'V 3.4.3 "Claughton Moor Shales" 23 3.4.4 "Moorcock Flagsll 23 4 IGNEOUS ROCKS 24 5 STRUCTURE 25 5.1 FAULTS 25 5.1.1 WNW to ESE-trending and NW to SE-trending faults 25 5.1.2 WSW to ENE trending faults 27 5.2 FOLDS 27 5.3 JOINTS 27 6 QUATERNARY 29 6.1 GLACIAL DEPOSITS AND EROSIONAL FEATURES 29 6.1.1 Till 29 6.1.2 Glaciofluvial Ice-contact Deposits 30 6.1.3 Glaciofluvial Sheet Deposits 31 6.1.4 Meltwater channels and other erosional features 31 6.2 FLANDRIAN DEPOSITS 32 6.2.1 River Terrace Deposits 32 6.2.2 Alluvial Fan Deposits 33 6.2.3 Alluvium 33 6.2.4 Peat 33 6.2.5 Head 33 6.2.6 Landslip 34 6.2.7 Made Ground 34 7 ECONOMIC GEOLOGY 35 7.1 STONE QUARRYING 35 7.2 BRICK MAKING 35 7.3 COAL . -

Roman Coins Elementary Manual

^1 If5*« ^IP _\i * K -- ' t| Wk '^ ^. 1 Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google PROTAT BROTHERS, PRINTBRS, MACON (PRANCi) Digitized by Google ROMAN COINS ELEMENTARY MANUAL COMPILED BY CAV. FRANCESCO gNECCHI VICE-PRBSIDENT OF THE ITALIAN NUMISMATIC SOaETT, HONORARY MEMBER OF THE LONDON, BELGIAN AND SWISS NUMISMATIC SOCIBTIES. 2"^ EDITION RKVISRD, CORRECTED AND AMPLIFIED Translated by the Rev<> Alfred Watson HANDS MEMBF,R OP THE LONDON NUMISMATIC SOCIETT LONDON SPINK & SON 17 & l8 PICCADILLY W. — I & 2 GRACECHURCH ST. B.C. 1903 (ALL RIGHTS RF^ERVED) Digitized by Google Arc //-/7^. K.^ Digitized by Google ROMAN COINS ELEMENTARY MANUAL AUTHOR S PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH EDITION In the month of July 1898 the Rev. A. W. Hands, with whom I had become acquainted through our common interests and stud- ieSy wrote to me asking whether it would be agreeable to me and reasonable to translate and publish in English my little manual of the Roman Coinage, and most kindly offering to assist me, if my knowledge of the English language was not sufficient. Feeling honoured by the request, and happy indeed to give any assistance I could in rendering this science popular in other coun- tries as well as my own, I suggested that it would he probably less trouble ii he would undertake the translation himselt; and it was with much pleasure and thankfulness that I found this proposal was accepted. It happened that the first edition of my Manual was then nearly exhausted, and by waiting a short time I should be able to offer to the English reader the translation of the second edition, which was being rapidly prepared with additions and improvements. -

Lune and Wyre Abstraction Licensing Strategy

Lune and Wyre abstraction licensing strategy February 2013 A licensing strategy to manage water resources sustainably Reference number/code [Sector Code] We are the Environment Agency. It's our job to look after your environment and make it a better place - for you, and for future generations. Your environment is the air you breathe, the water you drink and the ground you walk on. Working with business, Government and society as a whole, we are making your environment cleaner and healthier. The Environment Agency. Out there, making your environment a better place. Published by: Environment Agency Rio House Waterside Drive, Aztec West Almondsbury, Bristol BS32 4UD Tel: 03708 506506 Email: [email protected] www.environment-agency.gov.uk © Environment Agency All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced with prior permission of the Environment Agency. Environment Agency Lune and Wyre Licence Strategy 2 Foreword Water is the most essential of our natural resources, and it is our job to ensure that we manage and use it effectively and sustainably. The latest population growth and climate change predictions show that pressure on water resources is likely to increase in the future. In light of this, we have to ensure that we continue to maintain and improve sustainable abstraction and balance the needs of society, the economy and the environment. This licensing strategy sets out how we will manage water resources in the Lune and Wyre catchment and provides you with information on how we will manage existing abstraction licences and water availability for further abstraction. Both the Rivers Lune and Wyre have a high conservation value. -

Drusus Libo and the Succession of Tiberius

THE REPUBLIC IN DANGER This page intentionally left blank The Republic in Danger Drusus Libo and the Succession of Tiberius ANDREW PETTINGER 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries # Andrew Pettinger 2012 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2012 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available ISBN 978–0–19–960174–5 Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn To Hayley, Sue, and Graham Preface In 2003, while reading modern works on treason trials in Rome, I came across the prosecution of M. Scribonius Drusus Libo, an aristocrat destroyed in AD 16 for seeking out the opinions of a necromancer.