Audit and Inspection of Local Authorities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TELOS CORPORATION 19986 Ashburn Road Ashburn, Virginia 20147-2358 SUPPLEMENT to INFORMATION STATEMENT for the SPECIAL MEETING of STOCKHOLDERS to BE HELD MAY 31, 2007

TELOS CORPORATION 19986 Ashburn Road Ashburn, Virginia 20147-2358 SUPPLEMENT TO INFORMATION STATEMENT FOR THE SPECIAL MEETING OF STOCKHOLDERS TO BE HELD MAY 31, 2007 On May 11, 2007, Telos Corporation (the “Company”) mailed an Information Statement (the “Information Statement”) to the holders of the Company’s 12% Cumulative Exchangeable Redeemable Preferred Stock (the “Public Preferred Stock”) as of March 8, 2007 (the “Record Date”). The Information Statement was delivered in connection with the Special Meeting of Stockholders to be held on May 31, 2007 for the purpose of electing two Class D directors to the Company’s Board of Directors. The Company is furnishing to the holders of the Public Preferred Stock on the Record Date this Supplement to Information Statement in order to provide additional information concerning Seth W. Hamot, one of the Class D director nominees. The Company believes that this additional information is material and should be considered when deciding whether to vote for Mr. Hamot. As previously reported, the Company is involved in litigation with Costa Brava Partnership III, L.P. (“Costa Brava”), a holder of the Company’s Public Preferred Stock (the “Litigation”). As disclosed in the Information Statement, Mr. Hamot is the President of Costa Brava’s general partner and also the Managing Member of Costa Brava’s investment manager. The Company discovered recently that Mr. Hamot and Costa Brava’s counsel have been communicating with Wells Fargo & Company. Wells Fargo Foothill, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Wells Fargo & Company, is the lender under the Company’s revolving credit facility (the “Credit Facility”). -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Programmes and Investment

Agenda Meeting: Programmes and Investment Committee Date: Wednesday 21 July 2021 Time: 10:00 Place: Microsoft Teams Members Prof Greg Clark CBE (Chair) Dr Nina Skorupska CBE Dr Nelson Ogunshakin OBE (Vice-Chair) Dr Lynn Sloman MBE Heidi Alexander Ben Story Mark Phillips Government Special Representative Becky Wood Copies of the papers and any attachments are available on tfl.gov.uk How We Are Governed. How decisions will be taken The 2020 regulations that provided the flexibility to hold and take decisions by meetings held using videoconference expired on 6 May 2021. While social distancing measures will be lifted ahead of this meeting, there has not been sufficient time to prepare for a return to physical meetings, therefore Members will attend a videoconference briefing held in lieu of a meeting of the Committee. Any decisions that need to be taken within the remit of the Committee will be discussed at the briefing and, in consultation with available Members, will be taken by the Chair using Chair’s Action. A note of the decisions taken, including the key issues discussed, will be published on tfl.gov.uk. As far as possible, TfL will run the briefing as if it were a meeting but without physical attendance at a specified venue by Members, staff, the public or press. Papers will be published in advance on tfl.gov.uk How We Are Governed Apart from any discussion of exempt information, the briefing will be webcast live for the public and press on TfL’s YouTube channel. A guide for the press and public on attending and reporting meetings of local government bodies, including the use of film, photography, social media and other v1 2020 means is available on www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/Openness-in- Meetings.pdf. -

Council Agenda

Council Agenda City of Westminster Title: Council Meeting Meeting Date: Wednesday 2 May 2007 Time: 7.00pm Westminster Council House Venue: 97-113 Marylebone Road, London NW1 Members: All Councillors are hereby summoned to attend the Meeting for the transaction of the business set out below. Admission to the public gallery is by ticket, issued from the ground floor reception at Council House from 6.30pm. Please telephone if you are attending the meeting in a wheelchair or have difficulty walking up steps. There is wheelchair access by a side entrance. An Induction loop operates to enhance sound for anyone wearing a hearing aid or using a T transmitter. If you require any further information, please contact Nigel Tonkin. Tel: 020 7641 2756 Fax: 020 7641 8077 Minicom: 020 7641 5912 Email: [email protected] Corporate Website: www.westminster.gov.uk 2 1. Appointment of Relief Chairman To appoint a relief Chairman. 2. Minutes To sign the Minutes of the Meeting of the Council held on 21 March 2007. 3. Notice of Vacancy To note that Councillor Michael Vearncombe, Member for Marylebone High Street ward, resigned from the Council on Tuesday 27 March 2007. A by- election to fill the vacancy is being held on Thursday 3 May 2007. 4. Lord Mayor's Communications (a) The Lord Mayor to report that, at the invitation of Her Majesty, he attended and greeted the President of the Republic of Ghana and Mrs Kufour at their formal arrival in the UK at the start of their State Visit to this country. (b) The Lord Mayor to report that, alongside the Archbishops of Canterbury and York, he led the Walk of Witness march – starting from Whitehall Place, Westminster – to mark the 200 th anniversary of the abolition of the Slave Trade. -

Supplementary Information

HEIDI ALEXANDER POLITICAL EXPERIENCE 2010-2018 MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT FOR LEWISHAM EAST • Shadow Secretary of State for Health (2015-2016) • Deputy Shadow Minister for London (2013 – 2015) • Senior Opposition Whip (2013-2015) • Opposition Whip (2012-2013) • Member: ▪ Communities and Local Government Select Committee (2010-2012) ▪ Health Select Committee (2016-2017) ▪ Regulatory Reform Committee (2010-2012) ▪ Committee of Selection (2014-2015) • Co-founder & Director, Labour Campaign for the Single Market (2017-2018) 2006-2010 DEPUTY MAYOR & FULL-TIME CABINET MEMBER FOR REGENERATION LONDON BOROUGH OF LEWISHAM • Leadership responsibility for town centre redevelopment, transport, strategic housing and skills • London Councils Transport & Environment Committee Member (2006-2010) and TEC Executive Member (2006-2007) • Chair, Greater London Enterprise (2006-2008) • Director, Lewisham Local Education Partnership, responsible for the delivery of Lewisham’s Building Schools for the Future Programme (2007-2010) • Board Member, Thames Gateway London Partnership (2006-2010) 2004-2010 COUNCILLOR, LONDON BOROUGH OF LEWISHAM (EVELYN WARD) OTHER PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2005-2006 Campaign Co-ordinator, Clothes Aid 1999-2005 Parliamentary Researcher to Joan Ruddock MP 1998 6-month placement, Office of Cherie Booth QC, No.10 Downing St. 1996-1997 Holiday representative, First Choice Holidays EDUCATION 1998-1999 MA, European Urban and Regional Change (Distinction), Durham University 1993-1996 BA Hons, Geography (First Class), Durham University 1991-1993 New College Sixth Form, Swindon 1986-1991 Churchfields Comprehensive School, Swindon Page 1 This page is intentionally left blank Page 2 Statement by Heidi Alexander The Mayor’s vision for London is to deliver affordable public transport, healthier streets to encourage walking and cycling, and infrastructure that makes London fit for the future; a transport system that is the envy of the world. -

Back by Public Demand!

SEBRA NEWS W2 PROBABLY THE Back by MOST TALKED ABOUT Public Demand!GARDEN PARTY IN WESTMINSTER JOHN ZAMIT PRESENTS ISSUE No 93 A SEBRA PRODUCTION SUMMER 2018 “ “ ““ CARRYCARRY ONON NHSNHS ‘U’ THANK YOU NHS SEBRA SUMMER GARDEN PARTY 5 JULY 2018 ON THIS DAY 70 YEARS AGO THE NHS WAS BORN INTRODUCTION In this Issue From the THE GREATEST INTRODUCTION 10 BRIDGE GRAFITTI 40 LITTLE BARBER SHOP FROM THE CHAIRMAN 3 Chairman FROM THE EDITOR 4 Chairman: John Zamit SAFETY VALVE Email: [email protected] DELIVERY SCOOTER WOES 6 Phone: 020 7727 6104 BANK CLOSURE AT SHORT NOTICE 8 Mobile: 074 3825 8201 AN UNWANTED DEVELOPMENT? 9 Address: 2 Claremont Court LABOUR UPS ITS VOTE 11 Queensway, London W2 5HX AROUND BAYSWATER STATUE SPARKLING AGAIN 12 elcome to the Summer Also, we advised our local Councillors Also as you have may have read in the ON THE BUSES - HOLD ON TIGHT 13 2018 issue of SEBRA of our surprise at the publication of the press and on seen on TV, Business Rates "NOT FIT FOR PURPOSE" 17 NEWS W2. It's another report during a "purdah" period during can be crippling. (These rates are not set LUNCH IN THE SUN AT POMONA'S 21 bumper edition running to the local elections. As a result the report by Westminster Council and nor do they POLICING THE CAPITAL 24 Wover 120 pages. We delayed publishing was pulled by Stuart Love, Westminstrer receive the full amount levied). NEWCOMBE HOUSE BATTLE LINES 29 due to some late stories we wanted to City Council's Chief Executive. -

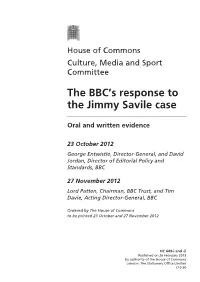

The BBC's Response to the Jimmy Savile Case

House of Commons Culture, Media and Sport Committee The BBC’s response to the Jimmy Savile case Oral and written evidence 23 October 2012 George Entwistle, Director-General, and David Jordan, Director of Editorial Policy and Standards, BBC 27 November 2012 Lord Patten, Chairman, BBC Trust, and Tim Davie, Acting Director-General, BBC Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 23 October and 27 November 2012 HC 649-i and -ii Published on 26 February 2013 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £10.50 The Culture, Media and Sport Committee The Culture, Media and Sport Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Department for Culture, Media and Sport and its associated public bodies. Current membership Mr John Whittingdale MP (Conservative, Maldon) (Chair) Mr Ben Bradshaw MP (Labour, Exeter) Angie Bray MP (Conservative, Ealing Central and Acton) Conor Burns MP (Conservative, Bournemouth West) Tracey Crouch MP (Conservative, Chatham and Aylesford) Philip Davies MP (Conservative, Shipley) Paul Farrelly MP (Labour, Newcastle-under-Lyme) Mr John Leech MP (Liberal Democrat, Manchester, Withington) Steve Rotheram MP (Labour, Liverpool, Walton) Jim Sheridan MP (Labour, Paisley and Renfrewshire North) Mr Gerry Sutcliffe MP (Labour, Bradford South) The following members were also members of the committee during the parliament. David Cairns MP (Labour, Inverclyde) Dr Thérèse Coffey MP (Conservative, Suffolk Coastal) Damian Collins MP (Conservative, Folkestone and Hythe) Alan Keen MP (Labour Co-operative, Feltham and Heston) Louise Mensch MP (Conservative, Corby) Mr Adrian Sanders MP (Liberal Democrat, Torbay) Mr Tom Watson MP (Labour, West Bromwich East) Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. -

London Assembly Mayor’S Question Time – Thursday 18 July 2019 Transcript of Item 5 – Questions to the Mayor

Appendix 2 London Assembly Mayor’s Question Time – Thursday 18 July 2019 Transcript of Item 5 – Questions to the Mayor 2019/14512 - “Shocking... horrifying... slow”: the Government’s response to removing flammable cladding post-Grenfell Andrew Dismore AM In a recent interview with the Evening Standard, London Fire Commissioner Dany Cotton described the Government’s action on building fire safety since the Grenfell Tower fire as “shocking... horrifying... slow” (Evening Standard, 4 July 2019) and warned that Londoners are at risk because of aluminium composite material on high rise blocks. LFC Cotton continued: “I don’t think anyone in government has responded in a satisfactory manner. We need more to be done. We need for it to be taken seriously.” Do you agree with her appraisal? Sadiq Khan (Mayor of London): I fully agree with London Fire Commissioner Dany Cotton [QFSM] that the Government has failed to do anywhere near enough on building fire safety since the fire at Grenfell Tower. Today, the cross-party Housing, Communities and Local Government Committee published a damning report, which agrees that the Government has been - and I quote - “far too slow to react” to the Grenfell Tower tragedy. After the devastating fire in June 2017, the Government promised urgent action to make everyone safe. More than two years later, our building regulation system is still unfit for purpose, we still lack clarity on the basic questions of whether certain types of cladding are safe, and tens of thousands of people continue to live in homes that may be unsafe, with leaseholders facing huge bills for interim safety measures and other safety works. -

FDN-274688 Disclosure

FDN-274688 Disclosure MP Total Adam Afriyie 5 Adam Holloway 4 Adrian Bailey 7 Alan Campbell 3 Alan Duncan 2 Alan Haselhurst 5 Alan Johnson 5 Alan Meale 2 Alan Whitehead 1 Alasdair McDonnell 1 Albert Owen 5 Alberto Costa 7 Alec Shelbrooke 3 Alex Chalk 6 Alex Cunningham 1 Alex Salmond 2 Alison McGovern 2 Alison Thewliss 1 Alistair Burt 6 Alistair Carmichael 1 Alok Sharma 4 Alun Cairns 3 Amanda Solloway 1 Amber Rudd 10 Andrea Jenkyns 9 Andrea Leadsom 3 Andrew Bingham 6 Andrew Bridgen 1 Andrew Griffiths 4 Andrew Gwynne 2 Andrew Jones 1 Andrew Mitchell 9 Andrew Murrison 4 Andrew Percy 4 Andrew Rosindell 4 Andrew Selous 10 Andrew Smith 5 Andrew Stephenson 4 Andrew Turner 3 Andrew Tyrie 8 Andy Burnham 1 Andy McDonald 2 Andy Slaughter 8 FDN-274688 Disclosure Angela Crawley 3 Angela Eagle 3 Angela Rayner 7 Angela Smith 3 Angela Watkinson 1 Angus MacNeil 1 Ann Clwyd 3 Ann Coffey 5 Anna Soubry 1 Anna Turley 6 Anne Main 4 Anne McLaughlin 3 Anne Milton 4 Anne-Marie Morris 1 Anne-Marie Trevelyan 3 Antoinette Sandbach 1 Barry Gardiner 9 Barry Sheerman 3 Ben Bradshaw 6 Ben Gummer 3 Ben Howlett 2 Ben Wallace 8 Bernard Jenkin 45 Bill Wiggin 4 Bob Blackman 3 Bob Stewart 4 Boris Johnson 5 Brandon Lewis 1 Brendan O'Hara 5 Bridget Phillipson 2 Byron Davies 1 Callum McCaig 6 Calum Kerr 3 Carol Monaghan 6 Caroline Ansell 4 Caroline Dinenage 4 Caroline Flint 2 Caroline Johnson 4 Caroline Lucas 7 Caroline Nokes 2 Caroline Spelman 3 Carolyn Harris 3 Cat Smith 4 Catherine McKinnell 1 FDN-274688 Disclosure Catherine West 7 Charles Walker 8 Charlie Elphicke 7 Charlotte -

Morgan Hayes, Including a Performance Diary and News of Recent Works, May Be Found At

Stainer & Bell CONTENTS Biographical Note .............................................................2 Music for Orchestra ..........................................................5 Music for String Orchestra ................................................6 Ensemble Works ...............................................................6 Works for Solo Instrument and Ensemble .......................10 Works for Flexible Instrumentation .................................11 Instrumental Chamber Music .........................................12 Works for Solo Piano .......................................................14 Choral Works ..................................................................16 Vocal Chamber Music .....................................................16 Works for Solo Voice .......................................................17 Discography....................................................................17 Alphabetical List of Works...............................................19 Ordering Information ......................................................20 Further information about the music of Morgan Hayes, including a performance diary and news of recent works, may be found at www.stainer.co.uk/hayes.html Cover design: Joe Lau August 2019 1 Morgan Hayes Born in 1973, Morgan Hayes reflects the cultural pluralism of his generation in his open and relaxed attitude to many kinds of musical expression. At the same time, he has pursued a single-minded artistic vision that has won him admirers from among the ranks -

Download (9MB)

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 2018 Behavioural Models for Identifying Authenticity in the Twitter Feeds of UK Members of Parliament A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF UK MPS’ TWEETS BETWEEN 2011 AND 2012; A LONGITUDINAL STUDY MARK MARGARETTEN Mark Stuart Margaretten Submitted for the degree of Doctor of PhilosoPhy at the University of Sussex June 2018 1 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................ 1 DECLARATION .................................................................................................................................. 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 5 FIGURES ........................................................................................................................................... 6 TABLES ............................................................................................................................................ -

MICHAEL DAVID NEVILL COBBOLD CBE DL January 2021

The Cobbold Family History Trust 14 Moorfields, Moorhaven, Ivybridge Devon, PL21 0XQ, UK Tel: + 44 (0) 1752 894498 www.cobboldfht.com [email protected] Patron: Lord Cobbold DL Ivry, Lady Freyberg MICHAEL DAVID NEVILL COBBOLD CBE DL January 2021 A natural born leader of men David Cobbold (1919-1994) #557 on the web family tree is deservedly one of the most revered members of our family. His considerable successes as a lawyer and a politician are well summarised in his obituary from The Times which we reproduce below, but that is not the reason for this piece. The Trust has just received, literally hot off the press, a copy of his “Memoirs of an Infantry Officer”. Through his letters to family members, we now have a fascinating account of the prime of his life between the ages of 23 and 26 and an insight into the war as it was waged in Egypt, Syria, Iran, Iraq, Italy, India and Burma. Cobbold family historians will love it for its frank expressions of a young man’s mind and historians will love it for his humble involvement in some highly significant events. The letters were transcribed by David’s grandmother, Hester (1865-1957) #290, edited by his son Chris #654 and typeset and published by his granddaughter, Sarah #4073. A few copies have been reserved for family and friends and are available by emailing Chris’s wife, Jeannie #655 on [email protected] They cost £10 including postage and the cheque should be payable to Chris & Jeannie Cobbold and sent to 42D Eastern Avenue, Reading, Berks RG1 5RY David Cobbolds Memoirs A gap in our record of his life has been handsomely filled. -

Culture, Media and Sport Committee

House of Commons Culture, Media and Sport Committee Future of the BBC Fourth Report of Session 2014–15 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 10 February 2015 HC 315 INCORPORATING HC 949, SESSION 2013-14 Published on 26 February 2015 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Culture, Media and Sport Committee The Culture, Media and Sport Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Department for Culture, Media and Sport and its associated public bodies. Current membership Mr John Whittingdale MP (Conservative, Maldon) (Chair) Mr Ben Bradshaw MP (Labour, Exeter) Angie Bray MP (Conservative, Ealing Central and Acton) Conor Burns MP (Conservative, Bournemouth West) Tracey Crouch MP (Conservative, Chatham and Aylesford) Philip Davies MP (Conservative, Shipley) Paul Farrelly MP (Labour, Newcastle-under-Lyme) Mr John Leech MP (Liberal Democrat, Manchester, Withington) Steve Rotheram MP (Labour, Liverpool, Walton) Jim Sheridan MP (Labour, Paisley and Renfrewshire North) Mr Gerry Sutcliffe MP (Labour, Bradford South) The following Members were also a member of the Committee during the Parliament: David Cairns MP (Labour, Inverclyde) Dr Thérèse Coffey MP (Conservative, Suffolk Coastal) Damian Collins MP (Conservative, Folkestone and Hythe) Alan Keen MP (Labour Co-operative, Feltham and Heston) Louise Mensch MP (Conservative, Corby) Mr Adrian Sanders MP (Liberal Democrat, Torbay) Mr Tom Watson MP (Labour, West Bromwich East) Powers The Committee is one of the Departmental Select Committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152.