Diet Quality, Food Groups and Nutrients Associated with the Gut Microbiota in a Nonwestern Population

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

16S Rdna Full-Length Assembly Sequencing Technology Analysis of Intestinal Microbiome in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 10 May 2021 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.634981 16S rDNA Full-Length Assembly Sequencing Technology Analysis of Intestinal Microbiome in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Sitong Dong 1, Jiao jiao 1, Shuangshuo Jia 2, Gaoyu Li 1, Wei Zhang 1, Kai Yang 3, Zhen Wang 3, Chao Liu 4,DaLi1 and Xiuxia Wang 1* Edited by: 1 Center of Reproductive Medicine, Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China, 2 Department of 3 Tao Lin, Orthopedic Surgery, Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China, Department of Research and 4 Baylor College of Medicine, Development, Germountx Company, Beijing, China, Department of Biological Information, Kangwei Medical Analysis United States Laboratory, Shenyang, China Reviewed by: Barbara Obermayer-Pietsch, Objective: To study the characteristics and relationship of the gut microbiota in patients Medical University of Graz, Austria with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Julio Plaza-Diaz, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Method: We recruited 45 patients with PCOS and 37 healthy women from the (CHEO), Canada Alberto Sola-Leyva, Reproductive Department of Shengjing Hospital. We recorded their clinical indexes, University of Granada, Spain and sequenced their fecal samples by 16S rDNA full-length assembly sequencing Yanli Pang, technology (16S-FAST). Peking University Third Hospital, China Result: We found decreased a diversity and different abundances of a series of microbial *Correspondence: species in patients with PCOS compared to healthy controls. We found LH and AMH were Xiuxia Wang fi [email protected] signi cantly increased in PCOS with Prevotella enterotype when compared to control women with Prevotella enterotype, while glucose and lipid metabolism level remained no Specialty section: significant difference, and situations were opposite in PCOS and control women with This article was submitted to Bacteroides enterotype. -

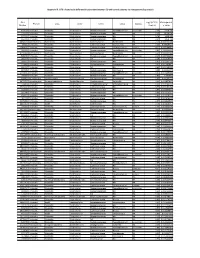

Appendix III: OTU's Found to Be Differentially Abundant Between CD and Control Patients Via Metagenomeseq Analysis

Appendix III: OTU's found to be differentially abundant between CD and control patients via metagenomeSeq analysis OTU Log2 (FC CD / FDR Adjusted Phylum Class Order Family Genus Species Number Control) p value 518372 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.16 5.69E-08 194497 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 2.15 8.93E-06 175761 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 5.74 1.99E-05 193709 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 2.40 2.14E-05 4464079 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales Bacteroidaceae Bacteroides NA 7.79 0.000123188 20421 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Lachnospiraceae Coprococcus NA 1.19 0.00013719 3044876 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Lachnospiraceae [Ruminococcus] gnavus -4.32 0.000194983 184000 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.81 0.000306032 4392484 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales Bacteroidaceae Bacteroides NA 5.53 0.000339948 528715 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.17 0.000722263 186707 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales NA NA NA 2.28 0.001028539 193101 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 1.90 0.001230738 339685 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Peptococcaceae Peptococcus NA 3.52 0.001382447 101237 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales NA NA NA 2.64 0.001415109 347690 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Oscillospira NA 3.18 0.00152075 2110315 Firmicutes Clostridia -

Development of the Equine Hindgut Microbiome in Semi-Feral and Domestic Conventionally-Managed Foals Meredith K

Tavenner et al. Animal Microbiome (2020) 2:43 Animal Microbiome https://doi.org/10.1186/s42523-020-00060-6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Development of the equine hindgut microbiome in semi-feral and domestic conventionally-managed foals Meredith K. Tavenner1, Sue M. McDonnell2 and Amy S. Biddle1* Abstract Background: Early development of the gut microbiome is an essential part of neonate health in animals. It is unclear whether the acquisition of gut microbes is different between domesticated animals and their wild counterparts. In this study, fecal samples from ten domestic conventionally managed (DCM) Standardbred and ten semi-feral managed (SFM) Shetland-type pony foals and dams were compared using 16S rRNA sequencing to identify differences in the development of the foal hindgut microbiome related to time and management. Results: Gut microbiome diversity of dams was lower than foals overall and within groups, and foals from both groups at Week 1 had less diverse gut microbiomes than subsequent weeks. The core microbiomes of SFM dams and foals had more taxa overall, and greater numbers of taxa within species groups when compared to DCM dams and foals. The gut microbiomes of SFM foals demonstrated enhanced diversity of key groups: Verrucomicrobia (RFP12), Ruminococcaceae, Fusobacterium spp., and Bacteroides spp., based on age and management. Lactic acid bacteria Lactobacillus spp. and other Lactobacillaceae genera were enriched only in DCM foals, specifically during their second and third week of life. Predicted microbiome functions estimated computationally suggested that SFM foals had higher mean sequence counts for taxa contributing to the digestion of lipids, simple and complex carbohydrates, and protein. -

WO 2018/064165 A2 (.Pdf)

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2018/064165 A2 05 April 2018 (05.04.2018) W !P O PCT (51) International Patent Classification: Published: A61K 35/74 (20 15.0 1) C12N 1/21 (2006 .01) — without international search report and to be republished (21) International Application Number: upon receipt of that report (Rule 48.2(g)) PCT/US2017/053717 — with sequence listing part of description (Rule 5.2(a)) (22) International Filing Date: 27 September 2017 (27.09.2017) (25) Filing Language: English (26) Publication Langi English (30) Priority Data: 62/400,372 27 September 2016 (27.09.2016) US 62/508,885 19 May 2017 (19.05.2017) US 62/557,566 12 September 2017 (12.09.2017) US (71) Applicant: BOARD OF REGENTS, THE UNIVERSI¬ TY OF TEXAS SYSTEM [US/US]; 210 West 7th St., Austin, TX 78701 (US). (72) Inventors: WARGO, Jennifer; 1814 Bissonnet St., Hous ton, TX 77005 (US). GOPALAKRISHNAN, Vanch- eswaran; 7900 Cambridge, Apt. 10-lb, Houston, TX 77054 (US). (74) Agent: BYRD, Marshall, P.; Parker Highlander PLLC, 1120 S. Capital Of Texas Highway, Bldg. One, Suite 200, Austin, TX 78746 (US). (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DJ, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JO, JP, KE, KG, KH, KN, KP, KR, KW, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. -

Download (PDF)

Supplemental Table 1. OTU (Operational Taxonomic Unit) level taxonomic analysis of gut microbiota Case-control Average ± STDEV (%) Wilcoxon OTU Phylum Class Order Family Genus Patient (n = 15) Control (n = 16) p OTU_366 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Oscillospira 0.0189 ± 0.0217 0.00174 ± 0.00429 0.004** OTU_155 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Ruminococcus 0.0554 ± 0.0769 0.0161 ± 0.0461 0.006** OTU_352 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Ruminococcus 0.0119 ± 0.0111 0.00227 ± 0.00413 0.007** OTU_719 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Oscillospira 0.00150 ± 0.00190 0.000159 ± 0.000341 0.007** OTU_620 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Unclassified 0.00573 ± 0.0115 0.0000333 ± 0.000129 0.008** OTU_47 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Lachnospiraceae Lachnospira 1.44 ± 2.04 0.183 ± 0.337 0.011* OTU_769 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Unclassified 0.000857 ± 0.00175 0 0.014* OTU_747 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Anaerotruncus 0.000771 ± 0.00190 0 0.014* OTU_748 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Unclassified 0.0135 ± 0.0141 0.00266 ± 0.00420 0.015* OTU_81 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales [Barnesiellaceae] Unclassified 0.434 ± 0.436 0.0708 ± 0.126 0.017* OTU_214 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Unclassified 0.0254 ± 0.0368 0.00496 ± 0.00959 0.020* OTU_113 Actinobacteria Coriobacteriia Coriobacteriales Coriobacteriaceae Unclassified 0 0.189 ± 0.363 0.021* OTU_100 Bacteroidetes -

The Gut Microbiota and Disease

The Gut Microbiota and Disease: Segmented Filament Bacteria Exacerbates Kidney Disease in a Lupus Mouse Model Armin Munir1, Giancarlo Valiente1,2, Takuma Wada3, Jeffrey Hampton1, Lai-Chu Wu1,4, Aharon Freud5,6, Wael Jarjour1 1Division of Rheumatology and Immunology, The Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, 2Medical Scientist Training Program, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, 3Rheumatology and Applied Immunology, Saitama Medical University, 4Department of Biological Chemistry and Pharmacology, The Ohio State University, 5The James Cancer Hospital and Solove Research Institute, 6Department of Pathology, The Ohio State Wexner Medical Center Introduction Increased Glomerulonephritis in +SFB Mice ↑Inflammatory Cytokine Levels in +SFB Mice Gut Microbiome 16S rRNA Heat Map 15 weeks old 30 weeks old -SFB +SFB -SFB +SFB Background: -SFB +SFB Commensal organisms are a vital component to the host organism. A B C Lachnoclostridium uncultured bacterium Segmented Filament Bacteria (SFB) is a commensal bacterium found Lachnospiraceae NC2004 group uncultured bacterium A Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group uncultured bacterium in many animal species. SFB has been shown to exacerbate Roseburia uncultured bacterium Ruminiclostridium 6 uncultured bacterium inflammatory arthritis but has not been implicated in Systemic Lupus Anaerostipes ambiguous taxa Lachnoclostridium ambiguous taxa Erythematosus (SLE). The focus of our study was to understand the Lachnospiraceae GCA-9000066575 uncultured bacterium Family XIII AD3011 group ambiguous taxa broader relationship -

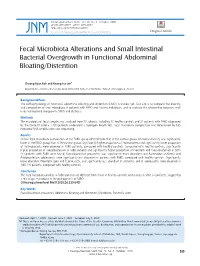

Fecal Microbiota Alterations and Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Functional Abdominal Bloating/Distention

J Neurogastroenterol Motil, Vol. 26 No. 4 October, 2020 pISSN: 2093-0879 eISSN: 2093-0887 https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm20080 JNM Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility Original Article Fecal Microbiota Alterations and Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Functional Abdominal Bloating/Distention Choong-Kyun Noh and Kwang Jae Lee* Department of Gastroenterology, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, Gyeonggi-do, Korea Background/Aims The pathophysiology of functional abdominal bloating and distention (FABD) is unclear yet. Our aim is to compare the diversity and composition of fecal microbiota in patients with FABD and healthy individuals, and to evaluate the relationship between small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) and dysbiosis. Methods The microbiota of fecal samples was analyzed from 33 subjects, including 12 healthy controls and 21 patients with FABD diagnosed by the Rome IV criteria. FABD patients underwent a hydrogen breath test. Fecal microbiota composition was determined by 16S ribosomal RNA amplification and sequencing. Results Overall fecal microbiota composition of the FABD group differed from that of the control group. Microbial diversity was significantly lower in the FABD group than in the control group. Significantly higher proportion of Proteobacteria and significantly lower proportion of Actinobacteria were observed in FABD patients, compared with healthy controls. Compared with healthy controls, significantly higher proportion of Faecalibacterium in FABD patients and significantly higher proportion of Prevotella and Faecalibacterium in SIBO (+) patients with FABD were found. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, was significantly more abundant, but Bacteroides uniformis and Bifidobacterium adolescentis were significantly less abundant in patients with FABD, compared with healthy controls. Significantly more abundant Prevotella copri and F. -

Faecalibacterium Prausnitzii: from Microbiology to Diagnostics and Prognostics

The ISME Journal (2017) 11, 841–852 © 2017 International Society for Microbial Ecology All rights reserved 1751-7362/17 www.nature.com/ismej MINI REVIEW Faecalibacterium prausnitzii: from microbiology to diagnostics and prognostics Mireia Lopez-Siles1, Sylvia H Duncan2, L Jesús Garcia-Gil1 and Margarita Martinez-Medina1 1Laboratori de Microbiologia Molecular, Departament de Biologia, Universitat de Girona, Girona, Spain and 2Microbiology Group, Rowett Institute of Nutrition and Health, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, UK There is an increasing interest in Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, one of the most abundant bacterial species found in the gut, given its potentially important role in promoting gut health. Although some studies have phenotypically characterized strains of this species, it remains a challenge to determine which factors have a key role in maintaining the abundance of this bacterium in the gut. Besides, phylogenetic analysis has shown that at least two different F. prausnitzii phylogroups can be found within this species and their distribution is different between healthy subjects and patients with gut disorders. It also remains unknown whether or not there are other phylogroups within this species, and also if other Faecalibacterium species exist. Finally, many studies have shown that F. prausnitzii abundance is reduced in different intestinal disorders. It has been proposed that F. prausnitzii monitoring may therefore serve as biomarker to assist in gut diseases diagnostics. In this mini- review, we aim to serve as an overview of F. prausnitzii phylogeny, ecophysiology and diversity. In addition, strategies to modulate the abundance of F. prausnitzii in the gut as well as its application as a biomarker for diagnostics and prognostics of gut diseases are discussed. -

Meta Analysis of Microbiome Studies Identifies Shared and Disease

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/134031; this version posted May 8, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. Meta analysis of microbiome studies identifies shared and disease-specific patterns Claire Duvallet1,2, Sean Gibbons1,2,3, Thomas Gurry1,2,3, Rafael Irizarry4,5, and Eric Alm1,2,3,* 1Department of Biological Engineering, MIT 2Center for Microbiome Informatics and Therapeutics 3The Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard 4Department of Biostatistics and Computational Biology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute 5Department of Biostatistics, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health *Corresponding author, [email protected] Contents 1 Abstract2 2 Introduction3 3 Results4 3.1 Most disease states show altered microbiomes ........... 5 3.2 Loss of beneficial microbes or enrichment of pathogens? . 5 3.3 A core set of microbes associated with health and disease . 7 3.4 Comparing studies within and across diseases separates signal from noise ............................... 9 4 Conclusion 10 5 Methods 12 5.1 Dataset collection ........................... 12 5.2 16S processing ............................ 12 5.3 Statistical analyses .......................... 13 5.4 Microbiome community analyses . 13 5.5 Code and data availability ...................... 13 6 Table and Figures 14 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/134031; this version posted May 8, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

And Dysenteric Pigs ISADORE M

APPLIED AND ENVIRONMENTAL MICROBIOLOGY, Nov. 1984, p. 964-969 Vol. 48, No. 5 0099-2240/84/110964-06$02.00/0 Copyright C) 1984, American Society for Microbiology Characterization of Predominant Bacteria from the Colons of Normal and Dysenteric Pigs ISADORE M. ROBINSON,* SHANNON C. WHIPP, JERRY A. BUCKLIN, AND MILTON J. ALLISON National Animal Disease Center, Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Ames, Iowa 50010 Received 20 April 1984/Accepted 7 August 1984 Bacterial populations adherent to the mucosa of the proximal colons of weaned, healthy pigs were compared with populations from pigs with dysentery induced by inoculation with a culture of Treponema hyodysenteriae. Isolates (136) representative of the predominant flora adherent to colonic epithelia of normal pigs and isolates (162) from pigs with dysentery were cultured anaerobically on a rumen fluid-based medium and characterized. Most (71%) of the isolates from colonic epithelia of normal pigs were gram positive, whereas 88% of the epithelia-associated isolates from pigs with dysentery were gram negative. The geometric mean of colony counts was 5.7 x 107/cm2 of colonic tissue from three normal pigs and 7.7 x 108/cm2 from four pigs with dysentery. A number of isolates obtained from contents of the lumens of normal pigs and pigs with dysentery were also characterized. Comparison of isolates from epithelial tissue and from contents of the lumens of the same pig indicated that these populations were different. Our results indicate that physiological changes that occur in the colons of pigs with dysentery are accompanied by marked changes in the microbial populations in the colons. -

Composition of Rabbit Caecal Microbiota and the Effects of Dietary Quercetin Supplementation and Sex Thereupon North M.K

W orld World Rabbit Sci. 2019, 27: 185-198 R abbit doi:10.4995/wrs.2019.11905 Science © WRSA, UPV, 2003 COMPOSITION OF RABBIT CAECAL MICROBIOTA AND THE EFFECTS OF DIETARY QUERCETIN SUPPLEMENTATION AND SEX THEREUPON NORTH M.K. *, DALLE ZOTTE A. †, HOFFMAN L.C. *‡ *Department of Animal Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Private Bag X1, Matieland, STELLENBOSCH 7602, South Africa. †Department of Animal Medicine, Production and Health, University of Padova, Agripolis, Viale dell’Università, 16, 35020 LEGNARO, Padova, Italy. ‡Centre for Nutrition and Food Sciences, Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation (QAAFI), The University of Queensland, Health and Food Sciences Precinct, 39 Kessels Road, COOPERS PLAINS 4108, Australia. Abstract: The purpose of this study was to add to the current understanding of rabbit caecal microbiota. This involved describing its microbial composition and linking this to live performance parameters, as well as determining the effects of dietary quercetin (Qrc) supplementation (2 g/kg feed) and sex on the microbial population. The weight gain and feed conversion ratio of twelve New Zealand White rabbits was measured from 5 to 12 wk old, blood was sampled at 11 wk old for the determination of serum hormone levels, and the rabbits were slaughtered and caecal samples collected at 13 wk old. Ion 16STM metagenome sequencing was used to determine the microbiota profile. The dominance of Firmicutes (72.01±1.14% of mapped reads), Lachnospiraceae (23.94±1.01%) and Ruminococcaceae (19.71±1.07%) concurred with previous reports, but variation both between studies and individual rabbits was apparent beyond this. Significant correlations between microbial families and live performance parameters were found, suggesting that further research into the mechanisms of these associations could be useful. -

000572305300015.Pdf(1.52

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Compositional and functional diferences of the mucosal microbiota along the intestine of healthy individuals Stefania Vaga1,15, Sunjae Lee1,15, Boyang Ji2, Anna Andreasson3,4,5, Nicholas J. Talley6, Lars Agréus7, Gholamreza Bidkhori1, Petia Kovatcheva‑Datchary8,9, Junseok Park10, Doheon Lee10, Gordon Proctor1, Stanislav Dusko Ehrlich11, Jens Nielsen2,12*, Lars Engstrand13* & Saeed Shoaie1,14* Gut mucosal microbes evolved closest to the host, developing specialized local communities. There is, however, insufcient knowledge of these communities as most studies have employed sequencing technologies to investigate faecal microbiota only. This work used shotgun metagenomics of mucosal biopsies to explore the microbial communities’ compositions of terminal ileum and large intestine in 5 healthy individuals. Functional annotations and genome‑scale metabolic modelling of selected species were then employed to identify local functional enrichments. While faecal metagenomics provided a good approximation of the average gut mucosal microbiome composition, mucosal biopsies allowed detecting the subtle variations of local microbial communities. Given their signifcant enrichment in the mucosal microbiota, we highlight the roles of Bacteroides species and describe the antimicrobial resistance biogeography along the intestine. We also detail which species, at which locations, are involved with the tryptophan/indole pathway, whose malfunctioning has been linked to pathologies including infammatory bowel disease. Our