A Walnut-Enriched Diet Affects Gut Microbiome in Healthy Caucasian Subjects: a Randomized, Controlled Trial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

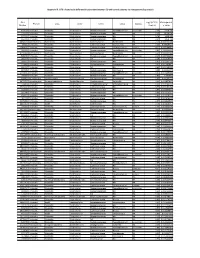

Appendix III: OTU's Found to Be Differentially Abundant Between CD and Control Patients Via Metagenomeseq Analysis

Appendix III: OTU's found to be differentially abundant between CD and control patients via metagenomeSeq analysis OTU Log2 (FC CD / FDR Adjusted Phylum Class Order Family Genus Species Number Control) p value 518372 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.16 5.69E-08 194497 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 2.15 8.93E-06 175761 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 5.74 1.99E-05 193709 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 2.40 2.14E-05 4464079 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales Bacteroidaceae Bacteroides NA 7.79 0.000123188 20421 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Lachnospiraceae Coprococcus NA 1.19 0.00013719 3044876 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Lachnospiraceae [Ruminococcus] gnavus -4.32 0.000194983 184000 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.81 0.000306032 4392484 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales Bacteroidaceae Bacteroides NA 5.53 0.000339948 528715 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.17 0.000722263 186707 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales NA NA NA 2.28 0.001028539 193101 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 1.90 0.001230738 339685 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Peptococcaceae Peptococcus NA 3.52 0.001382447 101237 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales NA NA NA 2.64 0.001415109 347690 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Oscillospira NA 3.18 0.00152075 2110315 Firmicutes Clostridia -

Development of the Equine Hindgut Microbiome in Semi-Feral and Domestic Conventionally-Managed Foals Meredith K

Tavenner et al. Animal Microbiome (2020) 2:43 Animal Microbiome https://doi.org/10.1186/s42523-020-00060-6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Development of the equine hindgut microbiome in semi-feral and domestic conventionally-managed foals Meredith K. Tavenner1, Sue M. McDonnell2 and Amy S. Biddle1* Abstract Background: Early development of the gut microbiome is an essential part of neonate health in animals. It is unclear whether the acquisition of gut microbes is different between domesticated animals and their wild counterparts. In this study, fecal samples from ten domestic conventionally managed (DCM) Standardbred and ten semi-feral managed (SFM) Shetland-type pony foals and dams were compared using 16S rRNA sequencing to identify differences in the development of the foal hindgut microbiome related to time and management. Results: Gut microbiome diversity of dams was lower than foals overall and within groups, and foals from both groups at Week 1 had less diverse gut microbiomes than subsequent weeks. The core microbiomes of SFM dams and foals had more taxa overall, and greater numbers of taxa within species groups when compared to DCM dams and foals. The gut microbiomes of SFM foals demonstrated enhanced diversity of key groups: Verrucomicrobia (RFP12), Ruminococcaceae, Fusobacterium spp., and Bacteroides spp., based on age and management. Lactic acid bacteria Lactobacillus spp. and other Lactobacillaceae genera were enriched only in DCM foals, specifically during their second and third week of life. Predicted microbiome functions estimated computationally suggested that SFM foals had higher mean sequence counts for taxa contributing to the digestion of lipids, simple and complex carbohydrates, and protein. -

WO 2018/064165 A2 (.Pdf)

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2018/064165 A2 05 April 2018 (05.04.2018) W !P O PCT (51) International Patent Classification: Published: A61K 35/74 (20 15.0 1) C12N 1/21 (2006 .01) — without international search report and to be republished (21) International Application Number: upon receipt of that report (Rule 48.2(g)) PCT/US2017/053717 — with sequence listing part of description (Rule 5.2(a)) (22) International Filing Date: 27 September 2017 (27.09.2017) (25) Filing Language: English (26) Publication Langi English (30) Priority Data: 62/400,372 27 September 2016 (27.09.2016) US 62/508,885 19 May 2017 (19.05.2017) US 62/557,566 12 September 2017 (12.09.2017) US (71) Applicant: BOARD OF REGENTS, THE UNIVERSI¬ TY OF TEXAS SYSTEM [US/US]; 210 West 7th St., Austin, TX 78701 (US). (72) Inventors: WARGO, Jennifer; 1814 Bissonnet St., Hous ton, TX 77005 (US). GOPALAKRISHNAN, Vanch- eswaran; 7900 Cambridge, Apt. 10-lb, Houston, TX 77054 (US). (74) Agent: BYRD, Marshall, P.; Parker Highlander PLLC, 1120 S. Capital Of Texas Highway, Bldg. One, Suite 200, Austin, TX 78746 (US). (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DJ, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JO, JP, KE, KG, KH, KN, KP, KR, KW, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. -

Download (PDF)

Supplemental Table 1. OTU (Operational Taxonomic Unit) level taxonomic analysis of gut microbiota Case-control Average ± STDEV (%) Wilcoxon OTU Phylum Class Order Family Genus Patient (n = 15) Control (n = 16) p OTU_366 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Oscillospira 0.0189 ± 0.0217 0.00174 ± 0.00429 0.004** OTU_155 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Ruminococcus 0.0554 ± 0.0769 0.0161 ± 0.0461 0.006** OTU_352 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Ruminococcus 0.0119 ± 0.0111 0.00227 ± 0.00413 0.007** OTU_719 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Oscillospira 0.00150 ± 0.00190 0.000159 ± 0.000341 0.007** OTU_620 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Unclassified 0.00573 ± 0.0115 0.0000333 ± 0.000129 0.008** OTU_47 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Lachnospiraceae Lachnospira 1.44 ± 2.04 0.183 ± 0.337 0.011* OTU_769 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Unclassified 0.000857 ± 0.00175 0 0.014* OTU_747 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Anaerotruncus 0.000771 ± 0.00190 0 0.014* OTU_748 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Unclassified 0.0135 ± 0.0141 0.00266 ± 0.00420 0.015* OTU_81 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales [Barnesiellaceae] Unclassified 0.434 ± 0.436 0.0708 ± 0.126 0.017* OTU_214 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Unclassified 0.0254 ± 0.0368 0.00496 ± 0.00959 0.020* OTU_113 Actinobacteria Coriobacteriia Coriobacteriales Coriobacteriaceae Unclassified 0 0.189 ± 0.363 0.021* OTU_100 Bacteroidetes -

The Isolation of Novel Lachnospiraceae Strains and the Evaluation of Their Potential Roles in Colonization Resistance Against Clostridium Difficile

The isolation of novel Lachnospiraceae strains and the evaluation of their potential roles in colonization resistance against Clostridium difficile Diane Yuan Wang Honors Thesis in Biology Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology College of Literature, Science, & the Arts University of Michigan, Ann Arbor April 1st, 2014 Sponsor: Vincent B. Young, M.D., Ph.D. Associate Professor of Internal Medicine Associate Professor of Microbiology and Immunology Medical School Co-Sponsor: Aaron A. King, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Ecology & Evolutionary Associate Professor of Mathematics College of Literature, Science, & the Arts Reader: Blaise R. Boles, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology College of Literature, Science, & the Arts 1 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Introduction 4 Clostridium difficile 4 Colonization Resistance 5 Lachnospiraceae 6 Objectives 7 Materials & Methods 9 Sample Collection 9 Bacterial Isolation and Selective Growth Conditions 9 Design of Lachnospiraceae 16S rRNA-encoding gene primers 9 DNA extraction and 16S ribosomal rRNA-encoding gene sequencing 10 Phylogenetic analyses 11 Direct inhibition 11 Bile salt hydrolase (BSH) detection 12 PCR assay for bile acid 7α-dehydroxylase detection 12 Tables & Figures Table 1 13 Table 2 15 Table 3 21 Table 4 25 Figure 1 16 Figure 2 19 Figure 3 20 Figure 4 24 Figure 5 26 Results 14 Isolation of novel Lachnospiraceae strains 14 Direct inhibition 17 Bile acid physiology 22 Discussion 27 Acknowledgments 33 References 34 2 Abstract Background: Antibiotic disruption of the gastrointestinal tract’s indigenous microbiota can lead to one of the most common nosocomial infections, Clostridium difficile, which has an annual cost exceeding $4.8 billion dollars. -

Breast Milk Microbiota: a Review of the Factors That Influence Composition

Published in "Journal of Infection 81(1): 17–47, 2020" which should be cited to refer to this work. ✩ Breast milk microbiota: A review of the factors that influence composition ∗ Petra Zimmermann a,b,c,d, , Nigel Curtis b,c,d a Department of Paediatrics, Fribourg Hospital HFR and Faculty of Science and Medicine, University of Fribourg, Switzerland b Department of Paediatrics, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia c Infectious Diseases Research Group, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Parkville, Australia d Infectious Diseases Unit, The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne, Parkville, Australia s u m m a r y Breastfeeding is associated with considerable health benefits for infants. Aside from essential nutrients, immune cells and bioactive components, breast milk also contains a diverse range of microbes, which are important for maintaining mammary and infant health. In this review, we summarise studies that have Keywords: investigated the composition of the breast milk microbiota and factors that might influence it. Microbiome We identified 44 studies investigating 3105 breast milk samples from 2655 women. Several studies Diversity reported that the bacterial diversity is higher in breast milk than infant or maternal faeces. The maxi- Delivery mum number of each bacterial taxonomic level detected per study was 58 phyla, 133 classes, 263 orders, Caesarean 596 families, 590 genera, 1300 species and 3563 operational taxonomic units. Furthermore, fungal, ar- GBS chaeal, eukaryotic and viral DNA was also detected. The most frequently found genera were Staphylococ- Antibiotics cus, Streptococcus Lactobacillus, Pseudomonas, Bifidobacterium, Corynebacterium, Enterococcus, Acinetobacter, BMI Rothia, Cutibacterium, Veillonella and Bacteroides. There was some evidence that gestational age, delivery Probiotics mode, biological sex, parity, intrapartum antibiotics, lactation stage, diet, BMI, composition of breast milk, Smoking Diet HIV infection, geographic location and collection/feeding method influence the composition of the breast milk microbiota. -

The Gut Microbiota and Disease

The Gut Microbiota and Disease: Segmented Filament Bacteria Exacerbates Kidney Disease in a Lupus Mouse Model Armin Munir1, Giancarlo Valiente1,2, Takuma Wada3, Jeffrey Hampton1, Lai-Chu Wu1,4, Aharon Freud5,6, Wael Jarjour1 1Division of Rheumatology and Immunology, The Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, 2Medical Scientist Training Program, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, 3Rheumatology and Applied Immunology, Saitama Medical University, 4Department of Biological Chemistry and Pharmacology, The Ohio State University, 5The James Cancer Hospital and Solove Research Institute, 6Department of Pathology, The Ohio State Wexner Medical Center Introduction Increased Glomerulonephritis in +SFB Mice ↑Inflammatory Cytokine Levels in +SFB Mice Gut Microbiome 16S rRNA Heat Map 15 weeks old 30 weeks old -SFB +SFB -SFB +SFB Background: -SFB +SFB Commensal organisms are a vital component to the host organism. A B C Lachnoclostridium uncultured bacterium Segmented Filament Bacteria (SFB) is a commensal bacterium found Lachnospiraceae NC2004 group uncultured bacterium A Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group uncultured bacterium in many animal species. SFB has been shown to exacerbate Roseburia uncultured bacterium Ruminiclostridium 6 uncultured bacterium inflammatory arthritis but has not been implicated in Systemic Lupus Anaerostipes ambiguous taxa Lachnoclostridium ambiguous taxa Erythematosus (SLE). The focus of our study was to understand the Lachnospiraceae GCA-9000066575 uncultured bacterium Family XIII AD3011 group ambiguous taxa broader relationship -

Characterization of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in the Species of the Rumen Microbiota

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13118-0 OPEN Characterization of antibiotic resistance genes in the species of the rumen microbiota Yasmin Neves Vieira Sabino1, Mateus Ferreira Santana1, Linda Boniface Oyama2, Fernanda Godoy Santos2, Ana Júlia Silva Moreira1, Sharon Ann Huws2* & Hilário Cuquetto Mantovani 1* Infections caused by multidrug resistant bacteria represent a therapeutic challenge both in clinical settings and in livestock production, but the prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes 1234567890():,; among the species of bacteria that colonize the gastrointestinal tract of ruminants is not well characterized. Here, we investigate the resistome of 435 ruminal microbial genomes in silico and confirm representative phenotypes in vitro. We find a high abundance of genes encoding tetracycline resistance and evidence that the tet(W) gene is under positive selective pres- sure. Our findings reveal that tet(W) is located in a novel integrative and conjugative element in several ruminal bacterial genomes. Analyses of rumen microbial metatranscriptomes confirm the expression of the most abundant antibiotic resistance genes. Our data provide insight into antibiotic resistange gene profiles of the main species of ruminal bacteria and reveal the potential role of mobile genetic elements in shaping the resistome of the rumen microbiome, with implications for human and animal health. 1 Departamento de Microbiologia, Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Viçosa, Minas Gerais, Brazil. 2 Institute for Global Food Security, School of Biological -

Faecalibacterium Prausnitzii: from Microbiology to Diagnostics and Prognostics

The ISME Journal (2017) 11, 841–852 © 2017 International Society for Microbial Ecology All rights reserved 1751-7362/17 www.nature.com/ismej MINI REVIEW Faecalibacterium prausnitzii: from microbiology to diagnostics and prognostics Mireia Lopez-Siles1, Sylvia H Duncan2, L Jesús Garcia-Gil1 and Margarita Martinez-Medina1 1Laboratori de Microbiologia Molecular, Departament de Biologia, Universitat de Girona, Girona, Spain and 2Microbiology Group, Rowett Institute of Nutrition and Health, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, UK There is an increasing interest in Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, one of the most abundant bacterial species found in the gut, given its potentially important role in promoting gut health. Although some studies have phenotypically characterized strains of this species, it remains a challenge to determine which factors have a key role in maintaining the abundance of this bacterium in the gut. Besides, phylogenetic analysis has shown that at least two different F. prausnitzii phylogroups can be found within this species and their distribution is different between healthy subjects and patients with gut disorders. It also remains unknown whether or not there are other phylogroups within this species, and also if other Faecalibacterium species exist. Finally, many studies have shown that F. prausnitzii abundance is reduced in different intestinal disorders. It has been proposed that F. prausnitzii monitoring may therefore serve as biomarker to assist in gut diseases diagnostics. In this mini- review, we aim to serve as an overview of F. prausnitzii phylogeny, ecophysiology and diversity. In addition, strategies to modulate the abundance of F. prausnitzii in the gut as well as its application as a biomarker for diagnostics and prognostics of gut diseases are discussed. -

Association Between Breast Milk Bacterial Communities and Establishment and Development of the Infant Gut Microbiome

Research JAMA Pediatrics | Original Investigation Association Between Breast Milk Bacterial Communities and Establishment and Development of the Infant Gut Microbiome Pia S. Pannaraj, MD, MPH; Fan Li, PhD; Chiara Cerini, MD; Jeffrey M. Bender, MD; Shangxin Yang, PhD; Adrienne Rollie, MS; Helty Adisetiyo, PhD; Sara Zabih, MS; Pamela J. Lincez, PhD; Kyle Bittinger, PhD; Aubrey Bailey, MS; Frederic D. Bushman, PhD; John W. Sleasman, MD; Grace M. Aldrovandi, MD Supplemental content IMPORTANCE Establishment of the infant microbiome has lifelong implications on health and immunity. Gut microbiota of breastfed compared with nonbreastfed individuals differ during infancy as well as into adulthood. Breast milk contains a diverse population of bacteria, but little is known about the vertical transfer of bacteria from mother to infant by breastfeeding. OBJECTIVE To determine the association between the maternal breast milk and areolar skin and infant gut bacterial communities. DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS In a prospective, longitudinal study, bacterial composition was identified with sequencing of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene in breast milk, areolar skin, and infant stool samples of 107 healthy mother-infant pairs. The study was conducted in Los Angeles, California, and St Petersburg, Florida, between January 1, 2010, and February 28, 2015. EXPOSURES Amount and duration of daily breastfeeding and timing of solid food introduction. MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES Bacterial composition in maternal breast milk, areolar skin, and infant stool by sequencing of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene. RESULTS In the 107 healthy mother and infant pairs (median age at the time of specimen collection, 40 days; range, 1-331 days), 52 (43.0%) of the infants were male. -

Prevalent Human Gut Bacteria Hydrolyse and Metabolise Important Food-Derived Mycotoxins and Masked Mycotoxins

toxins Article Prevalent Human Gut Bacteria Hydrolyse and Metabolise Important Food-Derived Mycotoxins and Masked Mycotoxins Noshin Daud 1, Valerie Currie 1 , Gary Duncan 1, Freda Farquharson 1, Tomoya Yoshinari 2, Petra Louis 1 and Silvia W. Gratz 1,* 1 Rowett Institute, University of Aberdeen, Foresterhill, Aberdeen AB25 2ZD, UK; [email protected] (N.D.); [email protected] (V.C.); [email protected] (G.D.); [email protected] (F.F.); [email protected] (P.L.) 2 Division of Microbiology, National Institute of Health Sciences, 3-25-26 Tonomachi, Kawasaki-ku, Kawasaki-shi, Kanagawa 210-9501, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 21 September 2020; Accepted: 9 October 2020; Published: 13 October 2020 Abstract: Mycotoxins are important food contaminants that commonly co-occur with modified mycotoxins such as mycotoxin-glucosides in contaminated cereal grains. These masked mycotoxins are less toxic, but their breakdown and release of unconjugated mycotoxins has been shown by mixed gut microbiota of humans and animals. The role of different bacteria in hydrolysing mycotoxin-glucosides is unknown, and this study therefore investigated fourteen strains of human gut bacteria for their ability to break down masked mycotoxins. Individual bacterial strains were incubated anaerobically with masked mycotoxins (deoxynivalenol-3-β-glucoside, DON-Glc; nivalenol-3-β-glucoside, NIV-Glc; HT-2-β-glucoside, HT-2-Glc; diacetoxyscirpenol-α-glucoside, DAS-Glc), or unconjugated mycotoxins (DON, NIV, HT-2, T-2, and DAS) for up to 48 h. Bacterial growth, hydrolysis of mycotoxin-glucosides and further metabolism of mycotoxins were assessed. -

Meta Analysis of Microbiome Studies Identifies Shared and Disease

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/134031; this version posted May 8, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. Meta analysis of microbiome studies identifies shared and disease-specific patterns Claire Duvallet1,2, Sean Gibbons1,2,3, Thomas Gurry1,2,3, Rafael Irizarry4,5, and Eric Alm1,2,3,* 1Department of Biological Engineering, MIT 2Center for Microbiome Informatics and Therapeutics 3The Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard 4Department of Biostatistics and Computational Biology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute 5Department of Biostatistics, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health *Corresponding author, [email protected] Contents 1 Abstract2 2 Introduction3 3 Results4 3.1 Most disease states show altered microbiomes ........... 5 3.2 Loss of beneficial microbes or enrichment of pathogens? . 5 3.3 A core set of microbes associated with health and disease . 7 3.4 Comparing studies within and across diseases separates signal from noise ............................... 9 4 Conclusion 10 5 Methods 12 5.1 Dataset collection ........................... 12 5.2 16S processing ............................ 12 5.3 Statistical analyses .......................... 13 5.4 Microbiome community analyses . 13 5.5 Code and data availability ...................... 13 6 Table and Figures 14 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/134031; this version posted May 8, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity.