Of Philippe Quinault: “A Very Agreeable Propaganda”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conflict of Obligations in Euripides' Alcestis

GOLDFARB, BARRY E., The Conflict of Obligations in Euripides' "Alcestis" , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 33:2 (1992:Summer) p.109 The Conflict of Obligations in Euripides' Alcestis Barry E. Goldfarb 0UT ALCESTIS A. M. Dale has remarked that "Perhaps no f{other play of Euripides except the Bacchae has provoked so much controversy among scholars in search of its 'real meaning'."l I hope to contribute to this controversy by an examination of the philosophical issues underlying the drama. A radical tension between the values of philia and xenia con stitutes, as we shall see, a major issue within the play, with ramifications beyond the Alcestis and, in fact, beyond Greek tragedy in general: for this conflict between two seemingly autonomous value-systems conveys a stronger sense of life's limitations than its possibilities. I The scene that provides perhaps the most critical test for an analysis of Alcestis is the concluding one, the 'happy ending'. One way of reading the play sees this resolution as ironic. According to Wesley Smith, for example, "The spectators at first are led to expect that the restoration of Alcestis is to depend on a show of virtue by Admetus. And by a fine stroke Euripides arranges that the restoration itself is the test. At the crucial moment Admetus fails the test.'2 On this interpretation 1 Euripides, Alcestis (Oxford 1954: hereafter 'Dale') xviii. All citations are from this editon. 2 W. D. Smith, "The Ironic Structure in Alcestis," Phoenix 14 (1960) 127-45 (=]. R. Wisdom, ed., Twentieth Century Interpretations of Euripides' Alcestis: A Collection of Critical Essays [Englewood Cliffs 1968]) 37-56 at 56. -

Jeudi 8 Juin 2017 Hôtel Ambassador

ALDE Hôtel Ambassador jeudi 8 juin 2017 Expert Thierry Bodin Syndicat Français des Experts Professionnels en Œuvres d’Art Les Autographes 45, rue de l’Abbé Grégoire 75006 Paris Tél. 01 45 48 25 31 - Facs 01 45 48 92 67 [email protected] Arts et Littérature nos 1 à 261 Histoire et Sciences nos 262 à 423 Exposition privée chez l’expert Uniquement sur rendez-vous préalable Exposition publique à l’ Hôtel Ambassador le jeudi 8 juin de 10 heures à midi Conditions générales de vente consultables sur www.alde.fr Frais de vente : 22 %T.T.C. Abréviations : L.A.S. ou P.A.S. : lettre ou pièce autographe signée L.S. ou P.S. : lettre ou pièce signée (texte d’une autre main ou dactylographié) L.A. ou P.A. : lettre ou pièce autographe non signée En 1re de couverture no 96 : [André DUNOYER DE SEGONZAC]. Ensemble d’environ 50 documents imprimés ou dactylographiés. En 4e de couverture no 193 : Georges PEREC. 35 L.A.S. (dont 6 avec dessins) et 24 L.S. 1959-1968, à son ami Roger Kleman. ALDE Maison de ventes spécialisée Livres-Autographes-Monnaies Lettres & Manuscrits autographes Vente aux enchères publiques Jeudi 8 juin 2017 à 14 h 00 Hôtel Ambassador Salon Mogador 16, boulevard Haussmann 75009 Paris Tél. : 01 44 83 40 40 Commissaire-priseur Jérôme Delcamp EALDE Maison de ventes aux enchères 1, rue de Fleurus 75006 Paris Tél. 01 45 49 09 24 - Facs. 01 45 49 09 30 - www.alde.fr Agrément n°-2006-583 1 1 3 3 Arts et Littérature 1. -

Kretan Cult and Customs, Especially in the Classical and Hellenistic Periods: a Religious, Social, and Political Study

i Kretan cult and customs, especially in the Classical and Hellenistic periods: a religious, social, and political study Thesis submitted for degree of MPhil Carolyn Schofield University College London ii Declaration I, Carolyn Schofield, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been acknowledged in the thesis. iii Abstract Ancient Krete perceived itself, and was perceived from outside, as rather different from the rest of Greece, particularly with respect to religion, social structure, and laws. The purpose of the thesis is to explore the bases for these perceptions and their accuracy. Krete’s self-perception is examined in the light of the account of Diodoros Siculus (Book 5, 64-80, allegedly based on Kretan sources), backed up by inscriptions and archaeology, while outside perceptions are derived mainly from other literary sources, including, inter alia, Homer, Strabo, Plato and Aristotle, Herodotos and Polybios; in both cases making reference also to the fragments and testimonia of ancient historians of Krete. While the main cult-epithets of Zeus on Krete – Diktaios, associated with pre-Greek inhabitants of eastern Krete, Idatas, associated with Dorian settlers, and Kretagenes, the symbol of the Hellenistic koinon - are almost unique to the island, those of Apollo are not, but there is good reason to believe that both Delphinios and Pythios originated on Krete, and evidence too that the Eleusinian Mysteries and Orphic and Dionysiac rites had much in common with early Kretan practice. The early institutionalization of pederasty, and the abduction of boys described by Ephoros, are unique to Krete, but the latter is distinct from rites of initiation to manhood, which continued later on Krete than elsewhere, and were associated with different gods. -

Les Opéras De Lully Remaniés Par Rebel Et Francœur Entre 1744 Et 1767 : Héritage Ou Modernité ? Pascal Denécheau

Les opéras de Lully remaniés par Rebel et Francœur entre 1744 et 1767 : héritage ou modernité ? Pascal Denécheau To cite this version: Pascal Denécheau. Les opéras de Lully remaniés par Rebel et Francœur entre 1744 et 1767 : héritage ou modernité ? : Deuxième séminaire de recherche de l’IRPMF : ”La notion d’héritage dans l’histoire de la musique”. 2007. halshs-00437641 HAL Id: halshs-00437641 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00437641 Preprint submitted on 1 Dec 2009 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. P. Denécheau : « Les opéras de Lully remaniés par Rebel et Francœur : héritage ou modernité ? » Les opéras de Lully remaniés par Rebel et Francœur entre 1744 et 1767 : héritage ou modernité ? Une grande partie des œuvres lyriques composées au XVIIe siècle par Lully et ses prédécesseurs ne se sont maintenues au répertoire de l’Opéra de Paris jusqu’à la fin du siècle suivant qu’au prix d’importants remaniements : les scènes jugées trop longues ou sans lien avec l’action principale furent coupées, quelques passages réécrits, un accompagnement de l’orchestre ajouté là où la voix n’était auparavant soutenue que par le continuo. -

Herminie a Performer's Guide to Hector Berlioz's Prix De Rome Cantata Rosella Lucille Ewing Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2009 Herminie a performer's guide to Hector Berlioz's Prix de Rome cantata Rosella Lucille Ewing Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Ewing, Rosella Lucille, "Herminie a performer's guide to Hector Berlioz's Prix de Rome cantata" (2009). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2043. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2043 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. HERMINIE A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO HECTOR BERLIOZ’S PRIX DE ROME CANTATA A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music and Dramatic Arts by Rosella Ewing B.A. The University of the South, 1997 M.M. Westminster Choir College of Rider University, 1999 December 2009 DEDICATION I wish to dedicate this document and my Lecture-Recital to my parents, Ward and Jenny. Without their unfailing love, support, and nagging, this degree and my career would never have been possible. I also wish to dedicate this document to my beloved teacher, Patricia O’Neill. You are my mentor, my guide, my Yoda; you are the voice in my head helping me be a better teacher and singer. -

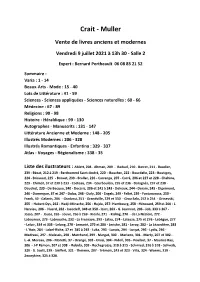

Crait - Muller

Crait - Muller Vente de livres anciens et modernes Vendredi 9 juillet 2021 à 13h 30 - Salle 2 Expert : Bernard Portheault 06 08 83 21 52 Sommaire : Varia : 1 - 14 Beaux-Arts - Mode : 15 - 40 Lots de Littérature : 41 - 59 Sciences - Sciences appliquées - Sciences naturelles : 60 - 66 Médecine : 67 - 89 Religions : 90 - 98 Histoire - Héraldique : 99 - 130 Autographes - Manuscrits : 131 - 147 Littérature Ancienne et Moderne : 148 - 205 Illustrés Modernes : 206 - 328 Illustrés Romantiques - Enfantina : 329 - 337 Atlas - Voyages - Régionalisme : 338 - 35 Liste des ilustrateurs : Ablett, 208 - Altman, 209 - Baduel, 210 - Barret, 211 - Baudier, 239 - Bécat, 212 à 219 - Berthommé Saint-André, 220 - Boucher, 222 - Bourdelle, 223 - Boutigny, 224 - Brissaud, 225 - Brouet, 239 - Bruller, 226 - Carrange, 207 - Carré, 206 et 227 et 228 - Chahine, 229 - Chimot, 37 et 230 à 233 - Cocteau, 234 - Courbouleix, 235 et 236 - Daragnès, 237 et 238 - Dauchot, 239 - De Becque, 240 - Decaris, 206 et 241 à 243 - Delvaux, 244 - Derain, 245 - Dignimont, 246 - Domergue, 37 et 247 - Dulac, 248 - Dufy, 206 - Engels, 249 - Falké, 239 - Fontanarosa, 250 - Frank, 40 - Galanis, 206 - Gradassi, 251 - Grandville, 329 et 330 - Grau Sala, 252 à 254 - Grinevski, 255 - Habert-Dys, 262 - Hadji-Minache, 256 - Hajdu, 257- Hambourg, 258 - Hérouard, 259 et 260 - L. Hervieu, 206 - Huard, 262 - Iacocleff, 348 et 350 - Icart, 263 - G. Jeanniot, 206 - Job, 333 à 367 - Josso, 207 - Jouas, 265 - Jouve, 266 à 269 - Kioshi, 271 - Kisling, 270 - de La Nézière, 272 - Laboureur, 273 - Labrouche, 232 - La Fresnaye, 293 - Lalau, 274 - Lalauze, 275 et 276 - Lebègue, 277 - Leloir, 334 et 335 - Lelong, 278 - Lemarié, 279 et 280 - Leriche, 281 - Leroy, 282 - La Lézardière, 283 - L’Hoir, 284 - Lobel-Riche, 37 et 285 à 292 - Luka, 293 - Lunois, 294 - Lurçat, 295 - Lydis, 296 - Madrassi, 297 - Malassis, 298 - Marchand, 299 - Margat, 300 - Mariano, 301 - Marty, 207 et 302 - L.-A. -

L'air Français, Un Art Intime

©Denis Rouvre ©Philippe Parent Les Arts Florissants – William Christie L’air français, un art intime Conciertos en seis ciudades de América Latina Les Arts Florissants presentan su primera gira en América Latina desde 2004: L’air français, un art intime El aria francesa, un arte íntimo Al final del reinado de Louis XIV; cambia el estilo de vida aristocrático, y el desarrollo de los salons da como resultado una vuelta de la sociedad elegante desde Versalles a París. Este fue el inicio de una nueva era socio-cultural: en música, esto provocó una evolución en la ambición y el formato. Aunque las formas a gran escala, sobre todo la Tragedia – lírica, continuaron siendo los modelos más avanzados para el entretenimiento de la corte, un arte más confidencial se desarrollaba, favoreciendo formas más modestas, como la sonata. En el ámbito de la música vocal, el air de cour se había vuelto muy popular desde el siglo XVI, y se le unió, a principios del XVIII, un nuevo género: La cantate. Esta forma se extendió a través de los círculos musicales franceses, coexistiendo con la más Antigua y muy en boga: cantata Italiana. La cantate francesa se distinguía de su prima italiana por su estilo, heredado de la tragédie lyrique, y en particular por la atención puesta en el texto. Estas obras eran la quintaesencia de “el buen gusto francés”, combinando los delicados ritmos de elocuencia poética con graciosas melodías. Estas arias à la française eran cantadas por uno o dos cantantes, acompañados de un clave, al que se le podían unir varios instrumentos: flauta, violín, viola, por ejemplo. -

Studia Varia from the J

OCCASIONAL PAPERS ON ANTIQUITIES, 10 Studia Varia from the J. Paul Getty Museum Volume 2 LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 2001 © 2001 The J. Paul Getty Trust Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 www. getty. edu Christopher Hudson, Publisher Mark Greenberg, Editor in Chief Project staff: Editors: Marion True, Curator of Antiquities, and Mary Louise Hart, Assistant Curator of Antiquities Manuscript Editor: Bénédicte Gilman Production Coordinator: Elizabeth Chapin Kahn Design Coordinator: Kurt Hauser Photographers, photographs provided by the Getty Museum: Ellen Rosenbery and Lou Meluso. Unless otherwise noted, photographs were provided by the owners of the objects and are reproduced by permission of those owners. Typography, photo scans, and layout by Integrated Composition Systems, Inc. Printed by Science Press, Div. of the Mack Printing Group Cover: One of a pair of terra-cotta arulae. Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum 86.AD.598.1. See article by Gina Salapata, pp. 25-50. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Studia varia. p. cm.—-(Occasional papers on antiquities : 10) ISBN 0-89236-634-6: English, German, and Italian. i. Art objects, Classical. 2. Art objects:—California—Malibu. 3. J. Paul Getty Museum. I. J. Paul Getty Museum. II. Series. NK665.S78 1993 709'.3 8^7479493—dc20 93-16382 CIP CONTENTS Coppe ioniche in argento i Pier Giovanni Guzzo Life and Death at the Hands of a Siren 7 Despoina Tsiafakis An Exceptional Pair of Terra-cotta Arulae from South Italy 25 Gina Salapata Images of Alexander the Great in the Getty Museum 51 Janet Burnett Grossman Hellenistisches Gold und ptolemaische Herrscher 79 Michael Pfrommer Two Bronze Portrait Busts of Slave Boys from a Shrine of Cobannus in Gaul 115 John Pollini Technical Investigation of a Painted Romano-Egyptian Sarcophagus from the Fourth Century A.D. -

Les Talens Lyriques the Ensemble Les Talens Lyriques, Which Takes Its

Les Talens Lyriques The ensemble Les Talens Lyriques, which takes its name from the subtitle of Jean-Philippe Rameau’s opera Les Fêtes d’Hébé (1739), was formed in 1991 by the harpsichordist and conductor Christophe Rousset. Championing a broad vocal and instrumental repertoire, ranging from early Baroque to the beginnings of Romanticism, the musicians of Les Talens Lyriques aim to throw light on the great masterpieces of musical history, while providing perspective by presenting rarer or little known works that are important as missing links in the European musical heritage. This musicological and editorial work, which contributes to its renown, is a priority for the ensemble. Les Talens Lyriques perform to date works by Monteverdi (L'Incoronazione di Poppea, Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in patria, L’Orfeo), Cavalli (La Didone, La Calisto), Landi (La Morte d'Orfeo), Handel (Scipione, Riccardo Primo, Rinaldo, Admeto, Giulio Cesare, Serse, Arianna in Creta, Tamerlano, Ariodante, Semele, Alcina), Lully (Persée, Roland, Bellérophon, Phaéton, Amadis, Armide, Alceste), Desmarest (Vénus et Adonis), Mondonville (Les Fêtes de Paphos), Cimarosa (Il Mercato di Malmantile, Il Matrimonio segreto), Traetta (Antigona, Ippolito ed Aricia), Jommelli (Armida abbandonata), Martin y Soler (La Capricciosa corretta, Il Tutore burlato), Mozart (Mitridate, Die Entführung aus dem Serail, Così fan tutte, Die Zauberflöte), Salieri (La Grotta di Trofonio, Les Danaïdes, Les Horaces, Tarare), Rameau (Zoroastre, Castor et Pollux, Les Indes galantes, Platée, Pygmalion), Gluck -

Lully's Psyche (1671) and Locke's Psyche (1675)

LULLY'S PSYCHE (1671) AND LOCKE'S PSYCHE (1675) CONTRASTING NATIONAL APPROACHES TO MUSICAL TRAGEDY IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ' •• by HELEN LLOY WIESE B.A. (Special) The University of Alberta, 1980 B. Mus., The University of Calgary, 1989 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS • in.. • THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES SCHOOL OF MUSIC We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October, 1991 © Helen Hoy Wiese, 1991 In presenting this hesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. (Signature) Department of Kos'iC The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date ~7 Ocf I DE-6 (2/68) ABSTRACT The English semi-opera, Psyche (1675), written by Thomas Shadwell, with music by Matthew Locke, was thought at the time of its performance to be a mere copy of Psyche (1671), a French tragedie-ballet by Moli&re, Pierre Corneille, and Philippe Quinault, with music by Jean- Baptiste Lully. This view, accompanied by a certain attitude that the French version was far superior to the English, continued well into the twentieth century. -

Castanets 1 Castanets

Castanets 1 Castanets Castanet(s) Castanets Percussion instrument Classification hand percussion Hornbostel–Sachs classification 111.141 (Directly struck concussive idiophone) Castanets are a percussion instrument (idiophone), used in Moorish, Ottoman, ancient Roman, Italian, Spanish and Portuguese music. The instrument consists of a pair of concave shells joined on one edge by a string. They are held in the hand and used to produce clicks for rhythmic accents or a ripping or rattling sound consisting of a rapid series of clicks. They are traditionally made of hardwood, although fibreglass is becoming increasingly popular. In practice a player usually uses two pairs of castanets. One pair is held in each hand, with the string hooked over the thumb and the castanets resting on the palm with the fingers bent over to support the other side. Each pair will make a sound of a slightly different Castanets seller in Granada, Spain pitch. The origins of the instrument are not known. The practice of clicking hand-held sticks together to accompany dancing is ancient, and was practised by both the Greeks and the Egyptians. In more modern times, the bones and spoons used in Minstrel show and jug band music can also be considered forms of the castanet. When used in an orchestral setting, castanets are sometimes attached to a handle, or mounted to a base to form a pair of machine castanets. This makes them easier to play, but also alters the sound, particularly for the machine castanets. It is possible to produce a roll on a pair of castanets in any of the three ways in Castanets 2 which they are held. -

Chaucer's Handling of the Proserpina Myth in The

CHAUCER’S HANDLING OF THE PROSERPINA MYTH IN THE CANTERBURY TALES by Ria Stubbs-Trevino A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a Major in Literature May 2017 Committee Members: Leah Schwebel, Chair Susan Morrison Victoria Smith COPYRIGHT by Ria Stubbs-Trevino 2017 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Ria Stubbs-Trevino, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my indomitable mother, Amber Stubbs-Aydell, who has always fought for me. If I am ever lost, I know that, inevitably, I can always find my way home to you. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are three groups of people I would like to thank: my thesis committee, my friends, and my family. I would first like to thank my thesis committee: Dr. Schwebel, Dr. Morrison, and Dr. Smith. The lessons these individuals provided me in their classrooms helped shape the philosophical foundation of this study, and their wisdom and guidance throughout this process have proven essential to the completion of this thesis.