Crossrail 2: Can Value for Money Be Improved? May 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4203 SLT Brochure 6/21/04 19:08 Page 1

4203 SLT brochure 6/21/04 19:08 Page 1 South London Trams Transport for Everyone The case for extensions to Tramlink 4203 SLT brochure 6/21/04 19:09 Page 2 South London Trams Introduction South London Partnership Given the importance of good Tramlink is a highly successful integrated transport and the public transport system. It is is the strategic proven success of Tramlink reliable, frequent and fast, offers a partnership for south in the region, South London high degree of personal security, Partnership together with the is well used and highly regarded. London. It promotes London Borough of Lambeth has the interests of south established a dedicated lobby This document sets out the case group – South London Trams – for extensions to the tram London as a sub-region to promote extensions to the network in south London. in its own right and as a Tramlink network in south London, drawing on the major contributor to the widespread public and private development of London sector support for trams and as a world class city. extensions in south London. 4203 SLT brochure 6/21/04 19:09 Page 4 South London Trams Transport for Everyone No need for a ramp operated by the driver “Light rail delivers The introduction of Tramlink has The tram has also enabled Integration is key to Tramlink’s been hugely beneficial for its local previously isolated local residents success. Extending Tramlink fast, frequent and south London community. It serves to travel to jobs, training, leisure provides an opportunity for the reliable services and the whole of the community, with and cultural activities – giving wider south London community trams – unlike buses and trains – them a greater feeling of being to enjoy these benefits. -

Rail Accident Report

Rail Accident Report Penetration and obstruction of a tunnel between Old Street and Essex Road stations, London 8 March 2013 Report 03/2014 February 2014 This investigation was carried out in accordance with: l the Railway Safety Directive 2004/49/EC; l the Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003; and l the Railways (Accident Investigation and Reporting) Regulations 2005. © Crown copyright 2014 You may re-use this document/publication (not including departmental or agency logos) free of charge in any format or medium. You must re-use it accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and you must give the title of the source publication. Where we have identified any third party copyright material you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This document/publication is also available at www.raib.gov.uk. Any enquiries about this publication should be sent to: RAIB Email: [email protected] The Wharf Telephone: 01332 253300 Stores Road Fax: 01332 253301 Derby UK Website: www.raib.gov.uk DE21 4BA This report is published by the Rail Accident Investigation Branch, Department for Transport. Penetration and obstruction of a tunnel between Old Street and Essex Road stations, London 8 March 2013 Contents Summary 5 Introduction 6 Preface 6 Key definitions 6 The incident 7 Summary of the incident 7 Context 7 Events preceding the incident 9 Events following the incident 11 Consequences of the incident 11 The investigation 12 Sources of evidence 12 Key facts and analysis -

The Operator's Story Appendix

Railway and Transport Strategy Centre The Operator’s Story Appendix: London’s Story © World Bank / Imperial College London Property of the World Bank and the RTSC at Imperial College London Community of Metros CoMET The Operator’s Story: Notes from London Case Study Interviews February 2017 Purpose The purpose of this document is to provide a permanent record for the researchers of what was said by people interviewed for ‘The Operator’s Story’ in London. These notes are based upon 14 meetings between 6th-9th October 2015, plus one further meeting in January 2016. This document will ultimately form an appendix to the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’ piece Although the findings have been arranged and structured by Imperial College London, they remain a collation of thoughts and statements from interviewees, and continue to be the opinions of those interviewed, rather than of Imperial College London. Prefacing the notes is a summary of Imperial College’s key findings based on comments made, which will be drawn out further in the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’. Method This content is a collation in note form of views expressed in the interviews that were conducted for this study. Comments are not attributed to specific individuals, as agreed with the interviewees and TfL. However, in some cases it is noted that a comment was made by an individual external not employed by TfL (‘external commentator’), where it is appropriate to draw a distinction between views expressed by TfL themselves and those expressed about their organisation. -

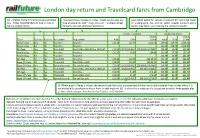

London Day Return and Travelcard Fares from Cambridge

London day return and Travelcard fares from Cambridge GA = Greater Anglia for trains to Liverpool Street Time restrictions Monday to Friday. Tickets can be used any Fares listed below for London Travelcard (for unlimited travel Any = Either Great Northern to King’s Cross or time at weekends. KGX = King’s Cross LST = Liverpool Street on underground, bus and rail within Greater London) and a GA to Liverpool Street Railcards may add additional restrictions London Day Return just covering the rail fare to London. London Travelcard London Day Return 2 Adult 2 Adult Ticket Operator Railcard Arr London Dep London Adult Child 2 Child Adult Child 2 Child Anytime Day Any No Any time Any time £47.50 £23.75 £142.50 £39.50 £19.75 £118.50 Anytime Day GA No Any time Any time £36.00 £18.00 £108.00 Off-Peak Any No After 1000 Not 1628 to 1901 KGX or 1835 LST £31.50 £15.75/£2.00[1] £78.15[G]/£67.00[1] £24.00 £2.00 £52.00 Anytime Day Any Yes Any time Any time £31.35 £9.05 £80.80 £26.05 £7.50 £67.10 Anytime Day GA Yes Any time Any time £23.75 £6.85 £61.20 Off-Peak GA No After 1000 Any time £25.40 £12.70 £62.95[G] £21.10 £2.00 £46.20 Super Off-Peak GA No After 1200 Not 1558 to 1902 £24.00 £12.00 £59.55[G] £16.40 £2.00 £36.80 Super Off-Peak Any No Sat and Sun only Sat and Sun only £22.50 £11.25/£2.00[1] £55.80[G]/£49.00[1] £16.50 £2.00 £37.00 Off-Peak Any Yes After 1000 Not 1628 to 1901 KGX or 1835 LST £20.80 £6.00/£2.00[1] £53.60/£45.60[1] £15.85 £2.00 £35.70 Off-Peak GA Yes After 1000 Any time £16.75 £4.85 £43.20 £13.95 £2.00 £31.90 Super Off-Peak GA Yes -

Oyster Conditions of Use on National Rail Services

Conditions of Use on National Rail services 1 October 2015 until further notice 1. Introduction 1.1. These conditions of use (“Conditions of Use”) set out your rights and obligations when using an Oyster card to travel on National Rail services. They apply in addition to the conditions set out in the National Rail Conditions of Carriage, which you can view and download from the National Rail website nationalrail.co.uk/nrcoc. Where these Conditions of Use differ from the National Rail Conditions of Carriage, these Conditions of Use take precedence when you are using your Oyster card. 1.2 When travelling on National Rail services, you will also have to comply with the Railway Byelaws. You can a get free copy of these at most staffed National Rail stations, or download a copy from the Department for Transport website dft.gov.uk. 1.3 All Train Companies operating services into the London Fare Zones Area accept valid Travelcards issued on Oyster cards, except Heathrow Express and Southeastern High Speed services between London St Pancras International and Stratford International. In addition, the following Train Companies accept pay as you go on Oyster cards for travel on their services within the London National Rail Pay As You Go Area. Abellio Greater Anglia Limited (trading as Greater Anglia) The Chiltern Railway Company Limited (trading as Chiltern Railways) First Greater Western Limited (trading as Great Western Railway) (including Heathrow Connect services between London Paddington and Hayes & Harlington) GoVia Thameslink Railway Limited (trading as Great Northern, as Southern and as Thameslink) London & Birmingham Railway Limited (trading as London Midland) London & South Eastern Railway Company (trading as Southeastern) (Special fares apply on Southeaster highspeed services between London St Pancras International and Stratford International). -

Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--History History 2016 Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945 Danielle K. Dodson University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.339 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dodson, Danielle K., "Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945" (2016). Theses and Dissertations--History. 40. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/history_etds/40 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--History by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

London Heathrow Airport

London Heathrow Airport Located 20 miles to the west of Central London. www.heathrowairport.com Heathrow Airport by Train The Heathrow Express is the fastest way to travel into Central London. Trains leave Heathrow Airport from approximately 5.12am until 11.40pm. For more information, and details of fares, visit the Heathrow Express website. Operating 150 services every day, Heathrow Express reaches Heathrow Central (Terminals 1 and 3) from Paddington in 15 minutes, with Terminal 5 a further four minutes. A free transfer service to Terminal 4 departs Heathrow Central every 15 minutes and takes four minutes. Heathrow Connect services run from London Paddington, calling at Ealing Broadway, West Ealing, Hanwell, Southall, Hayes & Harlington and Heathrow Central (Terminals 1 and 3). For Terminals 4 and 5, there's a free Heathrow Express tr ansfer service from Heathrow Central. Heathrow Connect journey time is about 25 minutes from Paddington to Heathrow Central. For more information, and details of fares, visit the Heathrow Connect website. Heathrow Airport by Tube The Piccadilly line connects Heathrow Airport to Central London and the rest of the Tube system. The Tube is cheaper than the Heathrow Express or Heathrow Connect but it takes a lot longer and is less comfortable. Tube services leave Heathrow every few minutes from approximately 5.10am (5.45am Sundays) to 11.35pm (11.25pm Sundays). Journey time to Piccadilly Circus is about 50 minutes. There are three Tube stations at Heathrow Airport, serving Terminals 1-3, Terminal 4 and Terminal 5. For more information, and details of fares, visit the Transport for London (TfL) website. -

Midland Main Line Upgrade Programme Economic Case Department for Transport

Midland Main Line Upgrade Programme Economic Case Department for Transport 30 August 2017 Midland Main Line Upgrade Programme Economic Case Report OFFICIAL SENSITIVE: COMMERCIAL Notice This document and its contents have been prepared and are intended solely for Department for Transport’s information and use in relation to Midland Main Line Upgrade Programme Business Case. Atkins assumes no responsibility to any other party in respect of or arising out of or in connection with this document and/or its contents. This document has 108 pages including the cover. Document history Job number: 5159267 Document ref: v4.0 Revision Purpose description Originated Checked Reviewed Authorised Date Interim draft for client Rev 1.0 - 18/08/2017 comment Revised draft for client Rev 2.0 18/08/2017 comment Revised draft addressing Rev 3.0 - 22/08/2017 client comment Rev 4.0 Final 30/08/2017 Client signoff Client Department for Transport Project Midland Main Line Upgrade Programme Document title Midland Main Line Upgrade Programme: KO1 Final Business Case Job no. 5159267 Copy no. Document reference Atkins Midland Main Line Upgrade Programme | Version 4.0 | 30 August 2017 | 5159267 2 Midland Main Line Upgrade Programme Economic Case Report OFFICIAL SENSITIVE: COMMERCIAL Table of contents Chapter Pages Executive Summary 7 1. Introduction 12 1.1. Background 12 1.2. Report Structure 13 2. Scope of the Appraisal 14 2.1. Introduction 14 2.2. Scenario Development 14 3. Timetable Development 18 3.1. Overview 18 4. Demand & Revenue Forecasting 26 4.1. Introduction 26 4.2. Forecasting methodology 26 4.3. Appraisal of Benefits 29 4.4. -

High Speed Two: Full Speed Ahead?

High Speed Two: Full Speed Ahead? The UK government has given the “green light” to the High Speed Two (HS2) rail project in its entirety, following the outcome of the Oakervee Review, ending months of speculation over the future of the scheme. Phase 2b of the project, linking Crewe to Manchester and Birmingham to Leeds via Sheffield, is subject to further review. It now forms part of an ambitious “High Speed North” integrated masterplan, including Northern Powerhouse Rail and other local rail improvements. What will this mean for landowners, occupiers and others who are directly affected by the HS2 scheme? Time will tell. However, the announcement is likely to be welcomed, as it provides certainty that the project will now proceed, although concerns over the long-term plans for delivery of Phase 2b will persist. HS2 Limited’s remit will be to “…focus solely on getting On all fronts, the government’s announcement gives phases 1 and 2A built on something approaching on time grounds for optimism. The government has pledged to learn and on budget” and, in respect of Phase 2b, new “delivery lessons from Phase 1 and improve how the project is being arrangements” will be put in place, but not before “…an delivered, highlighting the need for better communication and integrated plan for rail in the north” has been introduced. engagement with local communities impacted by the scheme. Grand plans no doubt, but close attention will be paid to the detail, including the enabling legislation required to deliver Major concerns will also remain over the delivery of the Phase 2a of the project and future plans for the design and scheme, including timescales for completion of each phase, delivery arrangements for Phase 2b. -

Hampton Court to Berrylands / Oct 2015

Crossrail 2 factsheet: Services between Berrylands and Hampton Court New Crossrail 2 services are proposed to serve all stations between Berrylands and Hampton Court, with 4 trains per hour in each direction operating directly to, and across central London. What is Crossrail 2? Crossrail 2 in this area Crossrail 2 is a proposed new railway serving London and the wider South East that could be open by 2030. It would connect the existing National Rail networks in Surrey and Hertfordshire with trains running through a new tunnel from Wimbledon to Tottenham Hale and New Southgate. Crossrail 2 will connect directly with National Rail, London Underground, London Overground, Crossrail 1, High Speed 1 international and domestic and High Speed 2 services, meaning passengers will be one change away from over 800 destinations nationwide. Why do we need Crossrail 2? The South West Main Line is one of the busiest and most congested routes in the country. It already faces capacity constraints and demand for National Rail services into Waterloo is forecast to increase by at least 40% by 2043. This means the severe crowding on the network will nearly double, and would likely lead to passengers being unable to board trains at some stations. Crossrail 2 provides a solution. It would free up space on the railway helping to reduce congestion, and would enable us to run more local services to central London that bypass the most congested stations. Transport improvements already underway will help offset the pressure in the short term. But we need Crossrail 2 to cope with longer term growth. -

Lillie Enclave” Fulham

Draft London Plan Consultation: ref. Chapter 7 Heritage - Neglect & Destruction February 2018 The “Lillie Enclave” Fulham Within a quarter mile radius of Lillie Bridge, by West Brompton station is A microcosm of the Industrial Revolution - A part of London’s forgotten heritage The enclave runs from Lillie Bridge along Lillie Road to North End Road and includes Empress (formerly Richmond) Place to the north and Seagrave Road, SW6 to the south. The roads were named by the Fulham Board of Works in 1867 Between the Grade 1 Listed Brompton Cemetery in RBKC and its Conservation area in Earl’s Court and the Grade 2 Listed Hermitage Cottages in H&F lies an astonishing industrial and vernacular area of heritage that English Heritage deems ripe for obliteration. See for example, COIL: https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1439963. (Former HQ of Piccadilly Line) The area has significantly contributed to: o Rail and motor Transport o Building crafts o Engineering o Rail, automotive and aero industries o Brewing and distilling o Art o Sport, Trade exhibitions and mass entertainment o Health services o Green corridor © Lillie Road Residents Association, February1 2018 Draft London Plan Consultation: ref. Chapter 7 Heritage - Neglect & Destruction February 2018 Stanford’s 1864 Library map: The Lillie Enclave is south and west of point “47” © Lillie Road Residents Association, February2 2018 Draft London Plan Consultation: ref. Chapter 7 Heritage - Neglect & Destruction February 2018 Movers and Shakers Here are some of the people and companies who left their mark on just three streets laid out by Sir John Lillie in the old County of Middlesex on the border of Fulham and Kensington parishes Samuel Foote (1722-1777), Cornishman dramatist, actor, theatre manager lived in ‘The Hermitage’. -

Silvertown Crossrail Station

Challenges Lessons Learned Policy. Ensuring that the message, delivery of the The project is still at an early stage and stakeholder station post Crossrail and demonstrating that the support and momentum will be the key. The impacts on the operational railway line, is clear stakeholder support will come in the form of to ensure that the support of the policy makers placing the station in the upcoming policy docu- and provide the project with a strong supporting ments, the Mayor’s Transport Strategy, London position. Plan and London Borough of Newham’s local plans Silvertown crossrail and polies update. To ensure that the station can Design. Incorporating the station into the local be supported in policy the momentum of dialogue area and demonstrating how it enables it to thrive and supporting technical work is essential. station and create an interchange for passengers to ensure the local residential and business can see the To become a Major East London transport hub London City Airport needs to create an interchange for benefits the station could bring. international, national and local travel for people in London and the South-East. The Silvertown Crossrail station supports the airport travellers through the creation of new Mayor’s vision for strategic growth by maximising visitor destinations, providing retail and leisure the regeneration potential of the Royal Docks Area opportunities, particularly at Royal Victoria and as well as providing faster links to key London at Silvertown Quays. The introduction of a station employment areas, and unlocking more land for close to the airport would achieve similar results homes and businesses.