Cell Dimensions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Common Features of All Cells Bacterial

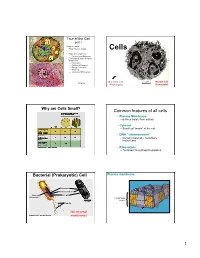

www.denniskunkel.com Tour of the Cell part 1 Today’s Topics • Finish Nucleic Acids Cells • Properties of all cells – Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes • Functions of Major Cellular Organelles – Information – Synthesis&Transport – Energy Conversion – Recycling – Structure and Movement Bacterial cell Animal Cell 9/12/12 (Prokaryote) (Eukaryote) 2 www.denniskunkel.com Common features of all cells • Plasma Membrane – defines inside from outside • Cytosol – Semifluid “inside” of the cell • DNA “chromosomes” - Genetic material – hereditary instructions • Ribosomes – “factories” to synthesize proteins 4 Plasma membrane Bacterial (Prokaryotic) Cell Ribosomes! Plasma membrane! Bacterial Cell wall! chromosome ! Phospholipid bilayer Proteins 0.5 !m! Flagella! No internal membranes 5 6 1 Figure 6.2b 1 cm Eukaryotic Cell Frog egg 1 mm Human egg 100 µm Most plant and animal cells 10 m µ Nucleus Most bacteria Light microscopy Mitochondrion 1 µm Super- 100 nm Smallest bacteria Viruses resolution microscopy Ribosomes 10 nm Electron microscopy Proteins Lipids 1 nm Small molecules Contains internal organelles 7 0.1 nm Atoms endoplasmicENDOPLASMIC RETICULUM reticulum (ER) ENDOPLASMIC RETICULUM (ER) NUCLEUS NUCLEUS Rough ER Smooth ER nucleus Rough ER Smooth ER Nucleus Plasma membrane Plasma membrane Centrosome Centrosome cytoskeletonCYTOSKELETON CYTOSKELETON Microfilaments You should Microfilaments Intermediate filaments know everything Intermediate filaments Microtubules in Fig 6.9 ribosomesRibosomes Microtubules Ribosomes cytosol GolgiGolgi apparatus apparatus Golgi apparatus Peroxisome Peroxisome In animal cells but not plant cells: In animal cells but not plant cells: Lysosome Lysosomes Lysosome Lysosomes Figure 6.9 Centrioles Figure 6.9 Centrioles Mitochondrion lysosome Flagella (in some plant 9sperm) Mitochondrion Flagella (in some plant10 sperm) mitochondrion Nuclear envelope Nucleus Nucleus 1 !m Nucleolus Chromatin Nuclear envelope: Inner membrane Outer membrane Pores Pore complex Rough ER Surface of nuclear envelope. -

Evidence for an Alternate Pathway for Lysosomal Enzyme Targeting (Oligosaccharides/Lysosomes/Phosphorylation) CHRISTOPHER A

Proc. NatL Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 80, pp. 775-779, February 1983 Cell Biology Identification and characterization of cells deficient in the mannose 6-phosphate receptor: Evidence for an alternate pathway for lysosomal enzyme targeting (oligosaccharides/lysosomes/phosphorylation) CHRISTOPHER A. GABEL, DANIEL E. GOLDBERG, AND STUART KORNFELD Departments of Internal Medicine and Biological Chemistry, Division of Hematology-Oncology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri 63110 Contributed by Stuart Kornfeld, November 3, 1982 ABSTRACT Newly synthesized lysosomal enzymes acquire dence that this cell line is deficient in Man-6-P receptor activity. phosphomannosyl units, which allow bindingofthe enzymes to the We also identify several additional cell lines that lack receptor mannose 6-phosphate receptor and subsequent translocation to activity yet possess high levels ofintracellular hydrolase activity. lysosomes. In some cell types, this sequence ofevents is necessary These data indicate that some cells possess pathways indepen- for the delivery ofthese enzymes to lysosomes. Using a slime mold dent of the Man-6-P receptor for the intracellular transport of lysosomal hydrolase as a probe, we have identified three murine acid hydrolases to lysosomes. cell lines that lack the receptor and one line that contains very low (3%) receptor activity. Each ofthese lines synthesizes the mannose MATERIALS AND METHODS 6-phosphate recognition marker on its lysosomal enzymes, but, Cells. BW5147 mouse lymphoma, P388D1 mouse macro- unlike cell lines with high levels of receptor, the cells accumulate MOPC 315 oligosaccharides containing phosphomonoesters. The receptor- phage, J774.2 mouse macrophage, mouse L cells, deficient lines possess high levels of intracellular acid hydrolase mouse myeloma, Chinese hamster ovary (CHO), and (human) activity, which is contained in dense granules characteristic of ly- HeLa cells were grown in suspension culture in a minimal es- sosomes. -

A Mitochondria–Lysosome Transport Pathway

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS Controlling enteric nerve Interestingly, inhibition of integrin signalling The authors used point mutations to establish cell migration or ROCK activity rescued directed migration of that residue Met 44 of actin was essential for the MEFs and normalized the migration of ENCCs F-actin-severing function of Mical. Manipulation A functional gastrointestinal system is in organ cultures. Although the precise function of Mical levels is known to generate abnormal dependent on the enteric nervous system, of Phactr4 remains to be discovered, these data bristle cell processes in Drosophila. In the present which is formed during embryogenesis through demonstrate its role in regulating lamellipodial study, mutation of the Met 44 actin residue colonization of the gut by enteric neural crest actin dynamics through cofilin activity suppressed Mical overexpression phenotypes cells (ENCCs). Now, Niswander and colleagues controlled by integrin and PP1 signalling. CKR and phenocopied Mical loss-of-function effects identify the protein phosphatase 1 (PP1)- and in Drosophila. Together, these findings establish actin-binding protein Phactr4 as a regulator actin as a direct substrate of Mical and reveal of directional and collective ENCC migration a specific oxidation-dependent mechanism (Genes Dev. 26, 69–81; 2012). Actin gets the oxidation to regulate actin filament dynamics and cell Analysis of mouse embryos expressing treatment from Mical processes in vivo. AIZ a Phactr4 mutation known to abolish PP1 binding revealed reduced enteric neuronal Mical, an enzyme mediating redox reactions, numbers and defective organization at is known to promote actin remodelling embryonic day 18.5, and reduced ENCC in response to semaphorin signalling by A mitochondria–lysosome numbers in the gut at earlier stages (E12.5). -

Phosphatases and Differentiation of the Golgi Apparatus

J. Cell Sci. 4, 455-497 (1969) 455 Printed in Great Britain PHOSPHATASES AND DIFFERENTIATION OF THE GOLGI APPARATUS MARIANNE DAUWALDER, W. G. WHALEY AND JOYCE E. KEPHART The Cell Research Institute, Tlie University of Texas at Austin, Texas, U.S.A. SUMMARY Cytochemical techniques for the electron microscopic localization of inosine diphosphatase, thiamine pyrophosphatase, and acid phosphatase have been applied to the developing root tip of Zea mays. Following formaldehyde fixation the Golgi apparatus of most of the cells showed reaction specificity for IDPase and TPPase. Following glutaraldehyde fixation marked localiza- tion of IDPase reactivity in the Golgi apparatus was limited to the root cap, the epidermis, and the phloem. A parallelism was apparent between the sequential morphological development of the apparatus for the secretion of a polysaccharide product, the fairly direct incorporation of tritiated glucose into the apparatus to become a component of this product and the develop- ment of the enzyme reactivity. Acid phosphatase, generally accepted as a lysosomal marker, was found in association with the Golgi apparatus in only a few cell types near the apex of the root. The localization was usually in a single cisterna at the face of the apparatus toward which the production of secretory vesicles builds up and associated regions of what may be smooth endoplasmic reticulum. Since the cell types involved were limited regions of the cap and epidermis and some initial cells, no functional correlates of the reactivity were apparent. Despite the presence of this lysosomal marker, no structures clearly identifiable as ' lysosomes' were found and the lack of reaction specificity in the vacuoles did not allow them to be so defined. -

Written Response #5

Written Response #5 • Draw and fill in the chart below about three different types of cells: Written Response #6-18 • In this true/false activity: • You and your partner will discuss the question, each of you will record your response and share your answer with the class. Be prepared to justify your answer. • You are allow to search answers. • You will be limited to 20 seconds per question. Written Response #6-18 6. The water-hating hydrophobic tails of the phospholipid bilayer face the outside of the cell membrane. 7. The cytoplasm essentially acts as a “skeleton” inside the cell. 8. Plant cells have special structures that are not found in animal cells, including a cell wall, a large central vacuole, and plastids. 9. Centrioles help organize chromosomes before cell division. 10. Ribosomes can be found attached to the endoplasmic reticulum. Written Response #6-18 11. ATP is made in the mitochondria. 12. Many of the biochemical reactions of the cell occur in the cytoplasm. 13. Animal cells have chloroplasts, organelles that capture light energy from the sun and use it to make food. 14. Small hydrophobic molecules can easily pass through the plasma membrane. 15. In cell-level organization, cells are not specialized for different functions. Written Response #6-18 16. Mitochondria contains its own DNA. 17. The plasma membrane is a single phospholipid layer that supports and protects a cell and controls what enters and leaves it. 18. The cytoskeleton is made from thread-like filaments and tubules. 3.2 HW 1. Describe the composition of the plasma membrane. -

Questions in Cell Biology

Name: Questions in Cell Biology Directions: The following questions are taken from previous IB Final Papers on the subject of cell biology. Answer all questions. This will serve as a study guide for the next quiz on Monday 11/21. 1. Outline the process of endocytosis. (Total 5 marks) 2. Draw a labelled diagram of the fluid mosaic model of the plasma membrane. (Total 5 marks) 3. The drawing below shows the structure of a virus. II I 10 nm (a) Identify structures labelled I and II. I: ...................................................................................................................................... II: ...................................................................................................................................... (2) (b) Use the scale bar to calculate the maximum diameter of the virus. Show your working. Answer: ..................................................... (2) (c) Explain briefly why antibiotics are effective against bacteria but not viruses. ............................................................................................................................................... ............................................................................................................................................... ............................................................................................................................................... .............................................................................................................................................. -

The Splicing Factor XAB2 Interacts with ERCC1-XPF and XPG for RNA-Loop Processing During Mammalian Development

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.20.211441; this version posted July 21, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The Splicing Factor XAB2 interacts with ERCC1-XPF and XPG for RNA-loop processing during mammalian development Evi Goulielmaki1*, Maria Tsekrekou1,2*, Nikos Batsiotos1,2, Mariana Ascensão-Ferreira3, Eleftheria Ledaki1, Kalliopi Stratigi1, Georgia Chatzinikolaou1, Pantelis Topalis1, Theodore Kosteas1, Janine Altmüller4, Jeroen A. Demmers5, Nuno L. Barbosa-Morais3, George A. Garinis1,2* 1. Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, Foundation for Research and Technology- Hellas, GR70013, Heraklion, Crete, Greece, 2. Department of Biology, University of Crete, Heraklion, Crete, Greece, 3. Instituto de Medicina Molecular João Lobo Antunes, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de Lisboa, Avenida Professor Egas Moniz, 1649-028 Lisboa, Portugal, 4. Cologne Center for Genomics (CCG), Institute for Genetics, University of Cologne, 50931, Cologne, Germany, 5. Proteomics Center, Netherlands Proteomics Center, and Department of Biochemistry, Erasmus University Medical Center, the Netherlands. Corresponding author: George A. Garinis ([email protected]) *: equally contributing authors bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.20.211441; this version posted July 21, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract RNA splicing, transcription and the DNA damage response are intriguingly linked in mammals but the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood. Using an in vivo biotinylation tagging approach in mice, we show that the splicing factor XAB2 interacts with the core spliceosome and that it binds to spliceosomal U4 and U6 snRNAs and pre-mRNAs in developing livers. -

Centrioles and the Formation of Rudimentary Cilia by Fibroblasts and Smooth Muscle Cells

CENTRIOLES AND THE FORMATION OF RUDIMENTARY CILIA BY FIBROBLASTS AND SMOOTH MUSCLE CELLS SERGEI SOROKIN, M.D. From the Department of Anatomy, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts ABSTRACT Cells from a variety of sources, principally differentiating fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells from neonatal chicken and mammalian tissues and from organ cultures of chicken duodenum, were used as materials for an electron microscopic study on the formation of rudimentary cilia. Among the differentiating tissues many cells possessed a short, solitary cilium, which projected from one of the cell's pair of centrioles. Many stages evidently intermediate in the fashioning of cilium from centriole were encountered and furnished the evidence from which a reconstruction of ciliogenesis was attempted. The whole process may be divided into three phases. At first a solitary vesicle appears at one end of a centriole. The ciliary bud grows out from the same end of the centriole and invaginates the sac, which then becomes the temporary ciliary sheath. During the second phase the bud lengthens into a shaft, while the sheath enlarges to contain it. Enlargement of the sheath is effected by the repeated appearance of secondary vesicles nearby and their fusion with the sheath. Shaft and sheath reach the surface of the cell, where the sheath fuses with the plasma membrane during the third phase. Up to this point, formation of cilia follows the classical descriptions in outline. Subsequently, internal development of the shaft makes the rudi- mentary cilia of the investigated material more like certain non-motile centriolar derivatives than motile cilia. The pertinent literature is examined, and the cilia are tentatively assigned a non-motile status and a sensory function. -

Centrosome Positioning in Vertebrate Development

Commentary 4951 Centrosome positioning in vertebrate development Nan Tang1,2,*,` and Wallace F. Marshall2,` 1Department of Anatomy, Cardiovascular Research Institute, The University of California, San Francisco, USA 2Department Biochemistry and Biophysics, The University of California, San Francisco, USA *Present address: National Institute of Biological Science, Beijing, China `Authors for correspondence ([email protected]; [email protected]) Journal of Cell Science 125, 4951–4961 ß 2012. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd doi: 10.1242/jcs.038083 Summary The centrosome, a major organizer of microtubules, has important functions in regulating cell shape, polarity, cilia formation and intracellular transport as well as the position of cellular structures, including the mitotic spindle. By means of these activities, centrosomes have important roles during animal development by regulating polarized cell behaviors, such as cell migration or neurite outgrowth, as well as mitotic spindle orientation. In recent years, the pace of discovery regarding the structure and composition of centrosomes has continuously accelerated. At the same time, functional studies have revealed the importance of centrosomes in controlling both morphogenesis and cell fate decision during tissue and organ development. Here, we review examples of centrosome and centriole positioning with a particular emphasis on vertebrate developmental systems, and discuss the roles of centrosome positioning, the cues that determine positioning and the mechanisms by which centrosomes respond to these cues. The studies reviewed here suggest that centrosome functions extend to the development of tissues and organs in vertebrates. Key words: Centrosome, Development, Mitotic spindle orientation Introduction radiating out to the cell cortex (Fig. 2A). In some cases, the The centrosome of animal cells (Fig. -

Studies on the Mechanisms of Autophagy: Formation of the Autophagic Vacuole W

Studies on the Mechanisms of Autophagy: Formation of the Autophagic Vacuole W. A. Dunn, Jr. Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, University of Florida College of Medicine, Gainesville, Florida 32610 Abstract. Autophagic vacuoles form within 15 min of tophagic vacuoles. All these results suggested that au- perfusing a liver with amino acid-depleted medium. tophagic vacuoles were not formed from plasma mem- These vacuoles are bound by a "smooth" double mem- brane, Golgi apparatus, or endosome constituents. An- brane and do not contain acid phosphatase activity. In tisera prepared against integral membrane proteins (14, Downloaded from http://rupress.org/jcb/article-pdf/110/6/1923/1059547/1923.pdf by guest on 26 September 2021 an attempt to identify the membrane source of these 25, and 40 kD) of the RER was found to label the in- vacuoles, I have used morphological techniques com- ner and outer limiting membranes of almost all na- bined with immunological probes to localize specific scent autophagic vacuoles. In addition, ribophorin II membrane antigens to the limiting membranes of was identified at the limiting membranes of many na- newly formed or nascent autophagic vacuoles. Anti- scent autophagic vacuoles. Finally, secretory proteins, bodies to three integral membrane proteins of the rat serum albumin and alpha2o-globulin, were localized plasma membrane (CE9, HA4, and epidermal growth to the lumen of the RER and to the intramembrane factor receptor) and one of the Golgi apparatus space between the inner and outer membranes of some (sialyltransferase) did not label these vacuoles. Inter- of these vacuoles. The results were consistent with the nalized epidermal growth factor and its membrane formation of autophagic vacuoles from ribosome-free receptor were not found in nascent autophagic vacu- regions of the RER. -

Nucleolus: a Central Hub for Nuclear Functions Olga Iarovaia, Elizaveta Minina, Eugene Sheval, Daria Onichtchouk, Svetlana Dokudovskaya, Sergey Razin, Yegor Vassetzky

Nucleolus: A Central Hub for Nuclear Functions Olga Iarovaia, Elizaveta Minina, Eugene Sheval, Daria Onichtchouk, Svetlana Dokudovskaya, Sergey Razin, Yegor Vassetzky To cite this version: Olga Iarovaia, Elizaveta Minina, Eugene Sheval, Daria Onichtchouk, Svetlana Dokudovskaya, et al.. Nucleolus: A Central Hub for Nuclear Functions. Trends in Cell Biology, Elsevier, 2019, 29 (8), pp.647-659. 10.1016/j.tcb.2019.04.003. hal-02322927 HAL Id: hal-02322927 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02322927 Submitted on 18 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Nucleolus: A Central Hub for Nuclear Functions Olga Iarovaia, Elizaveta Minina, Eugene Sheval, Daria Onichtchouk, Svetlana Dokudovskaya, Sergey Razin, Yegor Vassetzky To cite this version: Olga Iarovaia, Elizaveta Minina, Eugene Sheval, Daria Onichtchouk, Svetlana Dokudovskaya, et al.. Nucleolus: A Central Hub for Nuclear Functions. Trends in Cell Biology, Elsevier, 2019, 29 (8), pp.647-659. 10.1016/j.tcb.2019.04.003. hal-02322927 HAL Id: hal-02322927 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02322927 Submitted on 18 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. -

L Is for Lytic Granules: Lysosomes That Kill

Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1401Ž. 1998 146±156 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Review provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector L is for lytic granules: lysosomes that kill Lesley J. Page 1, Alison J. Darmon 2, Ruth Uellner, Gillian M. Griffiths ) MRC Lab for Molecular Cell Biology, UniÕersity College London, Gower St, London WC1E 6BT, UK Received 23 June 1997; revised 30 October 1997; accepted 31 October 1997 Contents 1. Introduction ................................................... 147 2. CTL function and biochemistry ....................................... 147 2.1. The function of CTL .......................................... 147 2.2. Mechanisms of killing.......................................... 147 2.3. Cytolytic proteins ............................................ 148 2.4. Target cell death ............................................. 149 2.5. Serial killing ............................................... 150 3. The lytic granule as a lysosome ....................................... 150 3.1. Lysosomal contents ........................................... 150 3.2. Lytic granules are acidic compartments ............................... 150 3.3. The lytic granule as an endocytic compartment ........................... 151 4. Lytic granules as secretory organelles ................................... 152 4.1. Sorting of lysosomal proteins ..................................... 152 4.2. Sorting of granzymes and perforin .................................. 152 5. Secretory lysosomes