1He Scottish Mountaineering Club Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adventure Travel Trip Itinerary

Adventure Travel Trip Itinerary Name of trip: Switzerland—Tour du Mont Blanc Dates of trip: August 20 - September 4, 2019 Leader: Debbie Markham Date Meals Day Day Activity (distances are approximate) Accommodation, Notes included Aug 20 Travel to Geneva, Switzerland (Tues) 1 Aug 21 Arrival in Geneva Overnight in Geneva at D (Wed) Please plan to arrive before 2 p.m. local time, to allow Hotel Tiffany. Double occupancy. enough time to get through customs, arrive at the hotel and soak up some much deserved down time prior to dinner. Transportation to the hotel from the airport is on your own. Trip leaders will provide suggestions for available transportation options. After checking in to the hotel, you are free to explore the city on your own. We will meet at 5 p.m. in the lobby of the hotel for a group meeting followed by a welcome dinner. 2 Aug 22 Shuttle to Chamonix Overnight in Chamonix at B, D (Thurs) After breakfast at the hotel, we will shuttle to Chamonix. Hotel Le Morgane, a 4-star Lunch and afternoon activities are on your own. You can boutique hotel with on-site pool explore the charming ski town of Chamonix and gaze at the and spa. Double occupancy. massive Mont Blanc as you savor gelato or take the cable car to Aiguille du Midi for a 360-degree view of the French, Swiss, and Italian Alps. The summit terrace is at 12,605 feet with a spectacular view of Mont Blanc on a clear day. We will meet up for a group dinner. -

Courmayeur Val Ferret Val Veny La Thuile Pré-Saint-Didier Morgex La

Sant’Orso fair Sankt Orso-Messe Matterhorn Tourist Courmayeur Mont Blanc Office Aosta roman and Val Ferret medieval town Monte Rosa Tourismusbüro Aosta römische und Val Veny mittelalterliche Stadt Astronomic observatory La Thuile Astronomische Observatorium Courmayeur Piazzale Monte Bianco, 13 Pré-Saint-Didier C E R V I N O 11013 Courmayeur AO Tel (+39) 0165 842060 Morgex M O N T E Fax (+39) 0165 842072 A N C O Breuil-Cervinia R O B I Col / Tunnel du S La Salle E A [email protected] T Tunnel du Grand-Saint-Bernard N O Mont-Blanc M Valtournenche Gressoney La Thuile La Trinité St-Rhémy-en-Bosses étroubles Via M. Collomb, 36 Ayas Courmayeur Valpelline 11016 La Thuile AO Gressoney-St-Jean Tel (+39) 0165 884179 Pré-Saint-Didier St-Barthélemy AOSTA Châtillon Brusson Fax (+39) 0165 885196 Sarre dalle flavio [email protected] • La Thuile Col du Fénis St-Vincent Petit-Saint-Bernard Pila VIC T A N guide società O • M L Verrès E D O Issogne C Cogne R A Valgrisenche P Bard Office Régional Champorcher Valsavarenche du Tourisme Rhêmes-Notre-Dame O DIS P A A AR Pont-St-Martin R N P Ufficio Regionale CO RA NAZIONALE G del Turismo Torino turistici operatori consorzi • Milano V.le Federico Chabod, 15 Genova G 11100 Aosta R A O Spas N P A R A D I S Therme 360° view over the whole chain of the Alps Gran Paradiso 360° Aussicht auf die gesamte Alpenkette Fénis (1), Issogne (2), Verrès (3), www.lovevda.it Traverse of Mont Sarre (4) castles and Blanc Bard Fortress (5) Überquerung des Schlösser Fénis (1), Issogne (2) Mont Blanc Verrès (3) und Bard -

Health and Wellbeing Brochure

HEALTH & WELLBEING IMMERSE YOURSELF IN NATURE BENMORE ESTATE | ISLE OF MULL | SCOTLAND "Meet me where the sky touches the sea. In the waves we will find our change of direction and just behind the clouds awaits a limitless blue sky" Sometimes, the only way to find yourself is to get completely lost in the wilderness. MIND & BODY Find a calmer sense of self and being in the wilderness of Scotland. Relax, unwind and rejuvenate in unspoilt and dramatic scenery. Take some time to heal your mind and relax your body, fully immersed in spectacular surroundings. SPIRIT & ADVENTURE Re-awaken your sense of adventure. Take to the seas and discover uninhabited islands, explore hidden beaches, and caves. Find a renewed sense of resilence and strength on a mountain top with endless views. Reconnect with nature. THE HIGHLIGHTS ALL INCLUSIVE LUXURY GUIDED BREAK DATE DURATION LOCATION PRICE Sunday 9th May - 5 full days, 6 nights Isle of Mull, Scotland £1,295 pp Saturday 15th May 2021 PRIVATE ISLAND ALL MEALS & EXPERT TUTION & ALL TRIPS AND LUXURY EXPLORATION DRINKS GUIDANCE EXCURSIONS ACCOMMODATION Island Exploration Luxury Accommodation Led by Expert Guides Dramatic Landscapes Immerse yourself in the wilderness of Scotland TRIP ITINERARY An illustrative itinerary, which is subject to change, to ensure full advantage is taken for the weather conditions for each day. Day 1 - A Warm Welcome Discover Knock House, a classic west highland sporting lodge, and your accommodation for the coming week. Explore the estate, meet your guides and the Benmore staff. Enjoy a first class meal with like minded enthusiasts in our traditional dining room, before retreating to your private bedroom to ready yourself for the coming week. -

Walks and Scrambles in the Highlands

Frontispiece} [Photo by Miss Omtes, SLIGACHAN BRIDGE, SGURR NAN GILLEAN AND THE BHASTEIR GROUP. WALKS AND SCRAMBLES IN THE HIGHLANDS. BY ARTHUR L. BAGLEY. WITH TWELVE ILLUSTRATIONS. Xon&on SKEFFINGTON & SON 34 SOUTHAMPTON STREET, STRAND, W.C. PUBLISHERS TO HIS MAJESTY THE KING I9H Richard Clav & Sons, Limiteu, brunswick street, stamford street s.e., and bungay, suffolk UNiVERi. CONTENTS BEN CRUACHAN ..... II CAIRNGORM AND BEN MUICH DHUI 9 III BRAERIACH AND CAIRN TOUL 18 IV THE LARIG GHRU 26 V A HIGHLAND SUNSET .... 33 VI SLIOCH 39 VII BEN EAY 47 VIII LIATHACH ; AN ABORTIVE ATTEMPT 56 IX GLEN TULACHA 64 X SGURR NAN GILLEAN, BY THE PINNACLES 7i XI BRUACH NA FRITHE .... 79 XII THROUGH GLEN AFFRIC 83 XIII FROM GLEN SHIEL TO BROADFORD, BY KYLE RHEA 92 XIV BEINN NA CAILLEACH . 99 XV FROM BROADFORD TO SOAY . 106 v vi CONTENTS CHAF. PACE XVI GARSBHEINN AND SGURR NAN EAG, FROM SOAY II4 XVII THE BHASTEIR . .122 XVIII CLACH GLAS AND BLAVEN . 1 29 XIX FROM ELGOL TO GLEN BRITTLE OVER THE DUBHS 138 XX SGURR SGUMA1N, SGURR ALASDAIR, SGURR TEARLACH AND SGURR MHIC CHOINNICH . I47 XXI FROM THURSO TO DURNESS . -153 XXII FROM DURNESS TO INCHNADAMPH . 1 66 XXIII BEN MORE OF ASSYNT 1 74 XXIV SUILVEN 180 XXV SGURR DEARG AND SGURR NA BANACHDICH . 1 88 XXVI THE CIOCH 1 96 1 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Toface page SLIGACHAN BRIDGE, SGURR NAN GILLEAN AND THE bhasteir group . Frontispiece BEN CRUACHAN, FROM NEAR DALMALLY . 4 LOCH AN EILEAN ....... 9 AMONG THE CAIRNGORMS ; THE LARIG GHRU IN THE DISTANCE . -31 VIEW OF SKYE, FROM NEAR KYLE OF LOCH ALSH . -

Journal 45 Autumn 2008

JOHN MUIR TRUST October 2008 No 45 Biodiversity: helping nature heal itself Saving energy: saving wild land Scotland’s missing lynx ADVERT 2 John Muir Trust Journal 45, October 2008 JOHN MUIR TRUST October 2008 No 45 Contents Nigel’s notes Foreword from the Chief Executive of the John Muir Trust, 3 The return of the natives: Nigel Hawkins Members air their views devotees – all those people who on re-introductions care passionately about wild land and believe in what the Trust is 5 Stained glass trying to do. commemorates John Muir During those 25 years there has been a constant process Bringing back trees to of change as people become 6 involved at different stages of our the Scottish Borders development and then move on, having made their mark in all 8 Biodiversity: sorts of different ways. Helping nature heal itself The John Muir Trust has We are going through another constantly seen change as period of change at the John Muir 11 Scotland’s missing lynx it develops and grows as Trust as two of us who have been the country’s leading wild very involved in the Trust and in land organisation. taking it forward, step down. In 12 Leave No Trace: the process, opportunities are created for new people to become Cleaning up the wilds Change is brought about by involved and to bring in their own what is happening in society, energy, freshness, experience, Inspiration Point the economy and in the political 13 skills and passion for our cause. world, with the Trust responding We can be very confident – based to all of these. -

FUTURE FOREST the BLACK WOOD RANNOCH, SCOTLAND

Gunnar’s Tree with the community, Nov. 23, 2013 (Collins & Goto Studio, 2013). FUTURE FOREST The BLACK WOOD RANNOCH, SCOTLAND Tim Collins and Reiko Goto Collins & Goto Studio, Glasgow, Scotland Art, Design, Ecology and Planning in the Public Interest with David Edwards Forest Research, Roslin, Scotland The Research Agency of the Forestry Commission Developed with: The Rannoch Paths Group Anne Benson, Artist, Chair, Rannoch and Tummel Tourist Association, Loch Rannoch Conservation Association. Jane Dekker, Rannoch and Tummel Tourist Association. Jeannie Grant, Tourism Projects Coordinator, Rannoch Paths Group. Bid Strachan, Perth and Kinross Countryside Trust. The project partners Charles Taylor, Rob Coope, Peter Fullarton, Tay Forest District, Forestry Commission Scotland. David Edwards and Mike Smith, Forest Research, Roslin. Paul McLennan, Perth and Kinross Countryside Trust. Richard Polley, Mark Simmons, Arts and Heritage, Perth and Kinross Council. Mike Strachan, Perth and Argyll Conservancy, Forestry Commission Scotland. Funded by: Creative Scotland: Imagining Natural Scotland Programme. The National Lottery / The Year of Natural Scotland. The Landscape Research Group. Forestry Commission Scotland. Forest Research. Future Forest: The Black Wood, Rannoch, Scotland Tim Collins, Reiko Goto and David Edwards Foreword by Chris Quine The Landscape Research Group, a charity founded in 1967, aims to promote research and understanding of the landscape for public benefit. We strive to stimulate research, transfer knowledge, encourage the exchange of ideas and promote practices which engage with landscape and environment. First published in UK, 2014 Forest Research Landscape Research Group Ltd Northern Research Station PO Box 1482 Oxford OX4 9DN Roslin, Midlothian EH25 9SY www.landscaperesearchgroup.com www.forestry.gov.uk/forestresearch © Crown Copyright 2014 ISBN 978-0-9931220-0-2 Paperback ISBN 978-0-9931220-1-9 EBook-PDF Primary funding for this project was provided by Creative Scotland, Year of Natural Scotland. -

Hermes' Portal Issue

Hermes’ Portal Issue #15 Hermes’ Portal Issue n° 15 October 2005 Who’s who . .3 Publisher’s corner . .3 Treasures of the Sea . .5 by Christopher Gribbon A Gazetteer of the Kingdom of Man and the Isles . .5 The Out Isles . .5 Running a Game on Man . .20 Appendix II: Dramatis Personae . .27 Appendix III: Island Families . .39 Appendix IV: Kings of Man and the Isles . .43 Appendix V: Bishops of Sodor and Man . .43 Appendix VI: Genealogy of the Royal Family of Man . .44 Appendix VI: Timeline of Major Events . .47 Appendix VII: Glossary . .49 Appendix VIII: Manx Gaelic . .52 Vis sources . .54 by Sheila Thomas and John Post Complicating the 5th Edition Combat System . .58 by Ty Larson Liturgical cursing . .61 by Sheila Thomas Omnibus Grimoire Scroll X: Vim . .65 by Andrew Gronosky Hermes’ portal Publisher: Hermes’ Portal Contributors: Christopher Gribbon, Andrew Gronosky, Tyler Larson, John Post, Sheila Thomas. Illustrations: Scott Beattie (p. 5, 15, 17, 32, 35), Radja Sauperamaniane (back), Angela Taylor (p. 4, 8, 11, 16, 18, 55, 57, 60, 62, 64, 67), Alexander White (cover, border & p. 22, 24) & Lacroix P., Sciences & Lettres au Moyen-Age … (Firmin-Didot, Paris, 1877). Editorial and proofreading help: Sheila Thomas, layout: Eric Kouris Thanks: All the people who submitted ideas, texts, illustrations or helped in the production of this issue. Hermes’ Portal is an independent publication dedicated to Ars Magica players. Hermes’ Portal is available through email only. Hermes’ Portal is not affiliated with Atlas Games or White Wolf Gaming Studio. References to trademarks of those companies are not intended to infringe upon the rights of those parties. -

Area Roads Capital Programme Progress 2019/20

Agenda 5 Item Report SR/19/19 No HIGHLAND COUNCIL Committee: Isle of Skye & Raasay Area Committee Date: 2 December 2019 Report Title: Area Roads Capital Programme Progress 2019/20 Report By: Executive Chief Officer Customer and Communities 1. Purpose/Executive Summary 1.1 This report provides an update on the work undertaken on the Area Capital Roads Programme for 2019/20 financial year. 2. Recommendations 2.1 Members are asked to note the contents of the report. 3. Implications 3.1 Resource – As detailed in report. 3.2 Legal – Under Section 34 of the Roads (Scotland) Act 1984 the Council, as Roads Authority, has a duty of care to manage and maintain the adopted road network. 3.3 Community (Equality, Poverty and Rural) – there is a risk that should road conditions contuse to deteriorate access to minor rural roads and residential streets may become more restrictive as precedence is given to maintaining the strategic road network. 3.4 Climate Change / Carbon Clever – in relation to Carbon Emissions the Service provides specialist training for all operatives in respect to fuel efficient driving, and route plans are in place to achieve the most efficient routing of vehicles. 3.5 Risk – Where a Roads Authority is unable to demonstrate that it has made adequate provision for the upkeep and safety of its adopted road network, as can be reasonably expected, it may lead to a greater risk to unable to defend claims made against it. 3.6 Gaelic - This report has no impact on Gaelic considerations 4. Area Capital Maintenance Programme 4.1 Finance The capital programme for 2019/20 was approved at the Isle of Skye and Raasay Committee on 3 December 2018. -

The Biology and Management of the River Dee

THEBIOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT OFTHE RIVERDEE INSTITUTEofTERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY NATURALENVIRONMENT RESEARCH COUNCIL á Natural Environment Research Council INSTITUTE OF TERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY The biology and management of the River Dee Edited by DAVID JENKINS Banchory Research Station Hill of Brathens, Glassel BANCHORY Kincardineshire 2 Printed in Great Britain by The Lavenham Press Ltd, Lavenham, Suffolk NERC Copyright 1985 Published in 1985 by Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Administrative Headquarters Monks Wood Experimental Station Abbots Ripton HUNTINGDON PE17 2LS BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATIONDATA The biology and management of the River Dee.—(ITE symposium, ISSN 0263-8614; no. 14) 1. Stream ecology—Scotland—Dee River 2. Dee, River (Grampian) I. Jenkins, D. (David), 1926– II. Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Ill. Series 574.526323'094124 OH141 ISBN 0 904282 88 0 COVER ILLUSTRATION River Dee west from Invercauld, with the high corries and plateau of 1196 m (3924 ft) Beinn a'Bhuird in the background marking the watershed boundary (Photograph N Picozzi) The centre pages illustrate part of Grampian Region showing the water shed of the River Dee. Acknowledgements All the papers were typed by Mrs L M Burnett and Mrs E J P Allen, ITE Banchory. Considerable help during the symposium was received from Dr N G Bayfield, Mr J W H Conroy and Mr A D Littlejohn. Mrs L M Burnett and Mrs J Jenkins helped with the organization of the symposium. Mrs J King checked all the references and Mrs P A Ward helped with the final editing and proof reading. The photographs were selected by Mr N Picozzi. The symposium was planned by a steering committee composed of Dr D Jenkins (ITE), Dr P S Maitland (ITE), Mr W M Shearer (DAES) and Mr J A Forster (NCC). -

Spring Newsletter 2005

Aberdeen Telephones Hillwalking Club SPRING NEWSLETTER 2005 CHAIRMAN’S CHAT trend will likely continue and we applied the Spring is in the air, with snowdrops and crocuses maximum fare of £12 quite a few times in 2004, over and daffodils in full bloom. As we emerge the AGM increased the maximum from £12 to £14. from dark winter days to lengthening daylight and warmer weather, the new season of walks planned Gratuities for both Braemar Mountain Rescue some time ago turns into the reality of walking in Team and Mountain Rescue Association of the countryside and climbing hills. Scotland were increased from £50 to £75. Our affiliations to North East Mountain Trust and Our walks were well attended during winter, and Ramblers’ Association were continued. we look forward to a new, exciting program. Even at this early stage of the year, we have had some The £10 annual membership fee remains good days such as the coastal walk from Bullers of unchanged. There was little support for reducing Buchan to Collieston, as well as not so good days - it to the £5 rate of a few years ago. the Mortlich-Craiglich walk was wet and misty with low cloud most of the day. The following were elected: - President ......................................................... Frank Kelly I am encouraged to see new members on our Vice President ....................................... Jim Henderson outings, and we extend a warm welcome. We look Secretary ................................................ Heather Eddie forward to getting to know you better during the Treasurer .............................................. Sally Henderson year, and hope you enjoy the Club. Booking Secretary ...................................... Alex Joiner Committee Members .... -

The Misty Isle of Skye : Its Scenery, Its People, Its Story

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES c.'^.cjy- U^';' D Cfi < 2 H O THE MISTY ISLE OF SKYE ITS SCENERY, ITS PEOPLE, ITS STORY BY J. A. MACCULLOCH EDINBURGH AND LONDON OLIPHANT ANDERSON & FERRIER 1905 Jerusalem, Athens, and Rome, I would see them before I die ! But I'd rather not see any one of the three, 'Plan be exiled for ever from Skye ! " Lovest thou mountains great, Peaks to the clouds that soar, Corrie and fell where eagles dwell, And cataracts dash evermore? Lovest thou green grassy glades. By the sunshine sweetly kist, Murmuring waves, and echoing caves? Then go to the Isle of Mist." Sheriff Nicolson. DA 15 To MACLEOD OF MACLEOD, C.M.G. Dear MacLeod, It is fitting that I should dedicate this book to you. You have been interested in its making and in its publica- tion, and how fiattering that is to an author s vanity / And what chief is there who is so beloved of his clansmen all over the world as you, or whose fiame is such a household word in dear old Skye as is yours ? A book about Skye should recognise these things, and so I inscribe your name on this page. Your Sincere Friend, THE A UTHOR. 8G54S7 EXILED FROM SKYE. The sun shines on the ocean, And the heavens are bhie and high, But the clouds hang- grey and lowering O'er the misty Isle of Skye. I hear the blue-bird singing, And the starling's mellow cry, But t4eve the peewit's screaming In the distant Isle of Skye. -

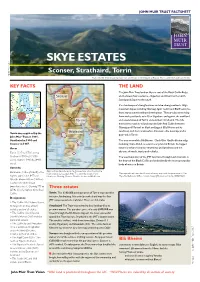

Skye Estates N a H C R E M

JOHN MUIR TRUST FACTSHEET T SKYE ESTATES N A H C R E M E Sconser, Strathaird, Torrin K I M From Gharbh-bheinn looking down to Loch Ainort and the Sound of Raasay. Marsco and Red Cuillin on the left. KEY FACTS THE LAND The John Muir Trust land on Skye is east of the Black Cuillin Ridge, Sconser and between four sea lochs – Sligachan and Ainort to the north, Scavaig and Slapin to the south. It’s a landscape of strong features and also strong contrasts. High mountain slopes including Glamaig, Sgurr na Stri and Blà Bheinn rise from sea to summit without interruption. They are also seen rising from wide peatlands, as in Glen Sligachan, and against the croftland Torrin and coastal woods of Torrin and southern Strathaird. The hills themselves may be red and rounded (the Red Cuillin between Glamaig and Marsco) or black and jagged (Bla Bheinn and its Strathaird satellites), and there’s also white limestone that outcrops and is Torrin was acquired by the quarried at Torrin. John Muir Trust in 1991, Strathaird in 1994 and The area west of the Blà Bheinn– Clach Glas–Garbh-bheinn ridge, Sconser in 1997. including Coire Dubh, is as wild as any land in Britain. Its rugged Areas nature is enhanced by its remoteness and loneliness and the absence of roads, tracks and vehicles. Torrin 2225 ha (5500 acres), Strathaird 6500 ha (15,000 The west boundary of the JMT land runs through Loch Coruisk, in acres), Sconser 3400 ha (8400 the heart of the Black Cuillin and undoubtedly the most spectacular acres).