Complex Feminist Conversations Judith Resnikt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wendy Williams Shy About Showing Hers Woff, of Course

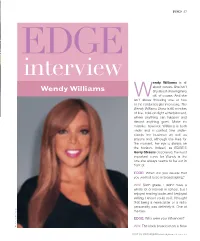

27 EDGE inte rview endy Williams is all about curves. She isn’t Wendy Williams shy about showing hers Woff, of course. And she isn’t above throwing one or two at the celebrities she interviews. The Wendy Williams Show is 60 minutes of live, hold-on-tight entertainment, where anything can happen and almost anything goes. Make no mistake, however. Williams is both under and in control. She under- stands her business as well as anyone and, although she lives for the moment, her eye is always on the horizon. Indeed, as EDGE’S Gerry Strauss discovered, the most important curve for Wendy is the one she always seems to be out in front of. EDGE: When did you decide that you wanted to be in broadcasting? WW: Sixth grade. I didn’t have a whole lot of interest in school, but I enjoyed reading books and I enjoyed writing. I knew I could do it. I thought that being a newscaster or a radio l e personality was definitely it. One of a h p a the two. R e n i d a N Who were your influences? EDGE: y b o t o h WW: The black broadcasters in New P VISIT US ON THE WEB www.edgemagonline.com 28 INTERVIEW York, like Sue Simmons, Vic Miles and Chi Chi Williams. In college, I majored in communications and minored in journalism. I immediately got involved with the college radio station, where I was reading news at the top of the hour. Radio was my second choice, actually, because I thought that you had to know an awful lot about music and you had to have an air of cool. -

Dj Issue Can’T Explain Just What Attracts Me to This Dirty Game

MAC MALL,WEST CLYDEOZONE COAST:CARSONPLUS E-40, TURF TALK OZONE MAGAZINE MAGAZINE OZONE FIGHT THE POWER: THE FEDS vs. DJ DRAMA THE SECOND ANNUAL DJ ISSUE CAN’T EXPLAIN JUST WHAT ATTRACTS ME TO THIS DIRTY GAME ME TO ATTRACTS JUST WHAT MIMS PIMP C BIG BOI LIL FLIP THREE 6 MAFIA RICK ROSS & CAROL CITY CARTEL SLICK PULLA SLIM THUG’s YOUNG JEEZY BOSS HOGG OUTLAWZ & BLOODRAW: B.G.’s CHOPPER CITY BOYZ & MORE APRIL 2007 USDAUSDAUSDA * SCANDALOUS SIDEKICK HACKING * RAPQUEST: THE ULTIMATE* GANGSTA RAP GRILLZ ROADTRIP &WISHLIST MORE GUIDE MAC MALL,WEST CLYDEOZONE COAST:CARSONPLUS REAL, RAW, & UNCENSORED SOUTHERN RAP E-40, TURF TALK FIGHT THE POWER: THE FEDS vs. DJ DRAMA THE SECOND ANNUAL DJ ISSUE MIMS PIMP C LIL FLIP THREE 6 MAFIA & THE SLIM THUG’s BOSS HOGG OUTLAWZ BIG BOI & PURPLE RIBBON RICK ROSS B.G.’s CHOPPER CITY BOYZ YOUNG JEEZY’s USDA CAROL CITY & MORE CARTEL* RAPQUEST: THE* SCANDALOUS ULTIMATE RAP SIDEKICK ROADTRIP& HACKING MORE GUIDE * GANGSTA GRILLZ WISHLIST OZONE MAG // 11 PUBLISHER/EDITOR-IN-CHIEF // Julia Beverly CHIEF OPERATIONS OFFICER // N. Ali Early MUSIC EDITOR // Randy Roper FEATURES EDITOR // Eric Perrin ART DIRECTOR // Tene Gooden ADVERTISING SALES // Che’ Johnson PROMOTIONS DIRECTOR // Malik Abdul MARKETING DIRECTOR // David Muhammad LEGAL CONSULTANT // Kyle P. King, P.A. SUBSCRIPTIONS MANAGER // Destine Cajuste ADMINISTRATIVE // Cordice Gardner, Kisha Smith CONTRIBUTORS // Alexander Cannon, Bogan, Carlton Wade, Charlamagne the God, Chuck T, E-Feezy, Edward Hall, Felita Knight, Iisha Hillmon, Jacinta Howard, Jaro Vacek, Jessica INTERVIEWS Koslow, J Lash, Jason Cordes, Jo Jo, Joey Columbo, Johnny Louis, Kamikaze, Keadron Smith, Keith Kennedy, Kenneth Brewer, K.G. -

Aaron's and 'The Wendy Williams Show' Surprise the Big Blue Bow Home Makeover Winner with Furniture, Electronics and Appliances

Aaron's and 'The Wendy Williams Show' Surprise the Big Blue Bow Home Makeover Winner With Furniture, Electronics and Appliances December 12, 2016 ATLANTA, Dec. 12, 2016 /PRNewswire/ -- Aaron's, Inc. (NYSE: AAN), a leader in the sales and lease ownership and specialty retailing of furniture, consumer electronics, home appliances and accessories, surprised the Dobbs family of Granville, West Virginia, as winners of the "Big Blue Bow Home Makeover" on Friday's Debmar-Mercury's "The Wendy Williams Show" with a home makeover of new furniture, appliances and electronics. Aaron's partnered once again with "Wendy" for its December "Big Blue Bow Event" holiday promotion that includes shopping deals and big-prize giveaways during the month, including a new blue 2017 Kia Forte EX. Throughout November, Aaron's and "Wendy" solicited entries for the "Big Blue Bow Home Makeover" by asking viewers why a home transformation would make a family reunion possible for the holidays. The winners, Anthony Harper and Jasmine Dobbs, recently moved into their first home but have too many bills and student loan bills to pay, so they could not afford a washer and dryer or to replace a worn-out living room set. They were hesitant to host family and friends for the holidays. The couple works fulltime, Anthony as an assistant director for the local parks and recreation department, and Jasmine as a paralegal who is also studying for her master's degree in project management. "We couldn't think of a better way to celebrate the holidays and the spirit of giving than by partnering with Wendy Williams to make a holiday family reunion possible for the Dobbs family," said Andrea Freeman, Aaron's Vice President of Marketing. -

Blogs and the Negative Stereotypes of African American Women on Reality Television

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Theses Department of Communication Summer 7-19-2013 The Reality Of Televised Jezebels and Sapphires: Blogs and the Negative Stereotypes of African American Women on Reality Television Safiya E. Reid Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses Recommended Citation Reid, Safiya E., "The Reality Of Televised Jezebels and Sapphires: Blogs and the Negative Stereotypes of African American Women on Reality Television." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2013. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses/100 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE REALITY OF TELEVISED JEZEBELS AND SAPPHIRES: BLOGS AND THE NEGATIVE STEREOTYPES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN ON REALITY TELEVISION by SAFIYA REID Under the Direction of Dr. Marian Meyers ABSTRACT Americans spend an average of 5.1 hours a day viewing television, with reality television as the most prevalent type of programming. Some of the top reality television shows feature African American women in negative and limiting roles. However, little research examines how the stereotypes presented on reality television about African American women are viewed by the audiences -

Tinashe Aquarius Release Date Announcement 0

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ! TINASHE ANNOUNCES DEBUT ALBUM AQUARIUS OUT OCTOBER 7 ON RCA RECORDS NEW SINGLE “PRETEND” FEATURING A$AP ROCKY TO BE RELEASED LATER THIS MONTH “2 ON” FEATURING SCHOOLBOY Q CONTINUES DOMINATION OF RHYTHMIC AIRPLAY CHART WITH A FOURTH WEEK AT #1, #3 ON THE HOT R&B SONGS CHART (August 18, 2014 – New York, NY) - Today singer-songwriter Tinashe is pleased to announce that her heavily anticipated debut studio album, Aquarius will be released on October 7th via RCA Records. The album, which Tinashe wrote and recorded between New York, London, and Los Angeles, finds the budding star at the forefront of modern R&B. Aquarius’ dynamic set of songs nod to her 90’s upbringing with their DNA planted firmly in the future. Tinashe shaped the album over the course of 2013 and 2014 with the likes of DJ Mustard, Redwine & DJ Marley Waters (all three producing on the ubiquitous “2 On” featuring ScHoolboy Q), Boi-1da, Jasper, Future, Stargate and several other surprise guests. “Aquarius is my official album introduction to the world and represents a new season of music and art,” says Tinashe. “I cannot wait to finally share with the world what I have been working so hard on for the past few years. This is just the beginning.” An official trailer for the album can be viewed here: http://youtu.be/ Mn4MOhBZLdA. The album’s first single “2 On” featuring ScHoolboy Q -- which The FADER calls Tinashe’s “star-making moment” and The New York Post recently dubbed one of 2014’s songs of the summer – has continued its climb up the charts and airwaves, reaching the summit on the Rhythmic Airplay chart, where it has remained at #1 for four weeks. -

THE NATIONAL ACADEMY of TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES ANNOUNCES the 38Th ANNUAL DAYTIME ENTERTAINMENT EMMY ® AWARD NOMINATIONS

THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES ANNOUNCES The 38th ANNUAL DAYTIME ENTERTAINMENT EMMY ® AWARD NOMINATIONS Daytime Emmy ® Awards to Be Telecast on June 19 th , 2011 On The CBS Television Network from the Las Vegas Hilton Wayne Brady to Host the Live Telecast Daytime Entertainment Creative Arts Emmy ® Awards Gala To be held at the Westin Bonaventure in LA on Friday, June 17, 2011 Pat Sajak and Alex Trebek to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award New York – May 11, 2011 – The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS) today announced the nominees for the 38th Annual Daytime Entertainment Emmy ® Awards. The Daytime Entertainment Emmy ® Awards will be broadcast from Las Vegas for the second year in a row on June 19 th , 2011 over the CBS Television Network, hosted by Wayne Brady, the Emmy ® Award winning actor, singer, and comedian and host of the CBS game show, Let’s Make a Deal . “It is with great pleasure that the Daytime Emmy ® Awards returns to the CBS Network again,” said Darryl Cohen, Chairman, NATAS. “The Daytime Emmy Awards is one of the cornerstones of our business and this year’s Las Vegas-based celebration, produced with our broadcast partner, Associated Television International, and hosted by Wayne Brady promises to be an exciting evening of entertainment.” The 38th Annual Daytime Entertainment Emmy ® Awards Lifetime Achievement Award will be presented to game show hosts Pat Sajak of Wheel of Fortune and Alex Trebek of Jeopardy! “In honoring Pat and Alex, we’re honoring not only two of the great game shows throughout the history of television,” said Cohen, “but two individuals whose talent and personality have given us an additional reason to tune in and watch.” Associated Television International’s (ATI) President and Emmy ® award-winning producer David McKenzie will serve as executive producer of the broadcast. -

The Legal Gaze and Women's Bodies

252 Columbia Journal of Gender and Law 32.2 “WE JUST LOOKED AT THEM AS ORDINARY PEOPLE LIKE WE WERE:” THE LEGAL GAZE AND WOMEN’S BODIES YXTA MAYA MURRAY* Abstract This Article analyzes the struggles of two female musicians who became caught up in the criminal justice system because they revealed their bodies. Using archival research and personal interviews, I tell the story of punk rocker Wendy O. Williams’ 1981-1984 obscenity and police brutality court battles. I also relay the life of Lorien Bourne, a disabled and lesbian rock-n-roller charged with disorderly conduct in Bowling Green, Ohio, in 2006. I examine how legal actors, including courts and jurors, viewed Williams and Bourne using classist, ableist, sexist, and homophobic optics. In so doing, I extend my previous work on legal “gazes,” or what I have called the legal practice of “peering.” I end the Article by looking to the women’s art and lives as correctives to oppressive manners of legal seeing. PRELUDE: TWO TALES OF FEMALE NUDITY AND THE COURTS “The prosecutors are the guys doing this for money. These guys are the real whores,”1 Mohawked and leather-clad2 Plasmatics frontwoman Wendy O. Williams shouted to jurors in the Cleveland Municipal Court3 in April 1981. They had just rendered a not-guilty © 2017 Murray. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits the user to copy, distribute, and transmit the work provided that the original author(s) and source are credited. * Professor, Loyola Law School. -

TAnisha SCott

ANISHA COTT T S CREATIVE & STAGE DIRECTOR/CHOREOGRAPHER *Winner of 2020 MTV Video Music Awards - Best Rock Video - Coldplay “Orphans” *Winner of 2020 Grammy Awards - Best Music Video - Lil Nas X feat. Billy Ray Cyrus “Old Town Road” *Winner of 2019 MTV Video Music Awards - Best Hip Hop Video - Cardi B “Money” *Nominated for 2019 MTV Video Music Awards - Best Pop Video - Cardi B feat. Bruno Mars “Please Me” *Nominated for 2019 MTV Video Music Awards - Best Hip Hop Video - Lil Nas X feat. Billy Ray Cyrus “Old Town Road” *Nominated for 2019 MTV Video Music Awards - Video of the Year - Lil Nas X feat. Billy Ray Cyrus “Old Town Road” *Winner of 2019 Billboard Music Awards – Top Streaming Song (Video) – Drake “In My Feelings” *Winner of 2012 MTVVideo Music Awards - Video of the Year - Rihanna “We Found Love” ***2016 MTV Vanguard Performance - Rihanna **Excellence in Choreography Nominee** Film/Television Title Role Network/Director Head of Choreography Dir: Rik Reinholdtsen/ Legendary Creative Producer HBO MAX Utopia Falls Choreographer Dir: RT/Hulu Grand Army Choreographer Netflix Rough Night Choreographer Dir. Lucia Aniello/Sony Pictures Kin Choreographer Dir. Jonathan & Josh Baker Money Monster Choreographer Dir: Jodi Foster Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Choreographer Netflix Love Beats Rhymes Choreographer Dir: Rza Sisters Choreographer Dir: Jason Moore Bring It On: All or Nothing Choreographer NBC/Universal Notorious Choreographer Dir: George Tillman Jr. The Blacklist: Redemption Choreographer NBC Sex and Drugs and Rock N Roll Choreographer FX America’s Top Model - Cycle 23 Choreographer/Guest Star VH1 Bring It!: The Girls’ Big NYC Trip Choreographer Lifetime Awakening - Pilot Choreographer CW LIT On-Air Host MTV We Can Dance – Pilot On-Air Host/Personality Vice/Live Nation The Next Step Guest Star Family Channel So You Think You Can Dance Canada Guest Choreographer CTV Bride Wars Assistant Choreographer Dir: Gary Winick Television – Performances Show Artist(s) Network The Kelly Clarkson Show Tiana Major9 NBC “Let’s Go Crazy”: The GRAMMY Salute To Prince H.E.R. -

Barbershop Politics

www.StamfordAdvocate.com | Wednesday, October 17, 2018 | Since 1829 | $2.00 Dearth of part-timers Baby found dead Officials call for Safe Haven law awareness driving By John Nickerson Capt. Richard Conklin said. ”This is a very tragic situation STAMFORD — A newborn when we see these and we have baby found dead Tuesday morn- seen some over the years,” Con- custodian ing at a city garbage and recy- klin said. cling facility has renewed calls to Scanlon said investigators raise awareness of the state’s have not determined the origin Safe Haven law. of the recyclables that were sort- OT costs Stamford Police Lt. Thomas ed Tuesday morning at the Tay- Scanlon said a City Carting em- lor Reed Place facility. He said ployee found the baby at the the materials came from Stam- $1.45M budgeted — but is company’s Glenbrook process- ford, Greenwich, Somers, N.Y., it enough for city schools? ing plant around 8:40 a.m. Tues- Oyster Bay, N.Y., and Andover, Michael Cummo / Hearst Connecticut Media day. Mass. Emergency personnel respond to a report of a dead An autopsy will be conducted A spokesman for City Carting By Angela Carella baby in a dumpster at the City Carting & Recycling on to determine how the boy died could not be reached for com- Taylor Reed Place in Stamford. and if he was stillborn, Police See Newborn on A5 STAMFORD — This month, for the second time, the elected officials who control the city’s purse strings asked to meet with the officials who manage school custodians. -

Primetime Emmy Ballot Watch the Emmy's

PRIMETIME EMMY BALLOT WATCH THE EMMY’S MAY , , : PM EST OUTSTANDING OUTSTANDING OUTSTANDING OUTSTANDING OUTSTANDING OUTSTANDING SPECIAL OUTSTANDING OUTSTANDING DIGITAL DAYTIME PRESCHOOL CHILDREN'S PRESCHOOL CHILDREN'S CHILDREN'S OR FAMILY CLASS ANIMATED DRAMA SERIES CULINARY PROGRAM DRAMA SERIES CHILDREN'S SERIES ANIMATED PROGRAM ANIMATED PROGRAM VIEWING SERIES PROGRAM The Bold and After Forever The Big Fun Crafty Disney Mickey Mouse Ask the StoryBots American Ninja Crow: The Legend Barefoot Contessa: the Beautiful Show Warrior Junior Cook Like a Pro The Bay The Series Hilda Daniel Tiger's DuckTales: The Days of Our Lives Dino Dana Neighborhood Chicken Soup for The Shadow War! Cook's Country Giants The Loud House Soul's Hidden Heroes General Hospital Miss Persona Elena of Avalor PAW Patrol: Eat. Race. Win. The New 30 Rise of the Teenage Odd Squad Mighty Pups Sesame Street Mutant Ninja Turtles Giada Entertains The Young and Youth Esme & Roy Top Chef Junior Tumble Leaf the Restless & Consequences Snug's House Welcome to Muppet Babies Halloween Special Lidia's Kitchen the Wayne The Who Was? Show Tumble Leaf Valerie's Home Cooking OUTSTANDING OUTSTANDING OUTSTANDING OUTSTANDING OUTSTANDING OUTSTANDING OUTSTANDING OUTSTANDING SPECIAL TRAVEL & ADVENTURE INFORMATIVE ENTERTAINMENT ENTERTAINMENT GAME SHOW LIFESTYLE PROGRAM MORNING PROGRAM CLASS SERIES PROGRAM TALK SHOW TALK SHOW NEWS PROGRAM Family Feud Ask This Old House Born to Explore with CBS Sunday Morning Access Live The Ellen Access Close Up With The Richard Wiese DeGeneres Show Hollywood -

SUNDERFOR LIFE Theirself- Titled Debut Album

NEWSSTAND PRICE S6.50 JULY 30, 2004 Alternative Says `Grace' RiZCMRIRHYTHMIC Three Days Grace climb to the top of R &R's Alternative chart this week with "Just Like You" (Jive/Zomba), the second hit from SUNDERFOR LIFE theirself- titled debut album. The song also In R &R's CHR /Rhythmic Special, CHR/Rhythmic Editor ranks No. 2 on the Dontay Thompson looks at ways the Rhythmic community Active Rock chart and is bonding with its audience through branding. Find insights follows the multiformat on using visual media and tips on spreading brand hit ";I Hate) Everything RAD/0 S RECORDS awareness for a lifetime. Demo profiles of the Rhythmic About You." www.radioandrecords.com audience are also featured. It all begins on Page 1. wrara WE BELIEVE! ON YO DESsIK. NOW! FROM THE FORTHCOMING NEW SINGLE SITS 2 1999 -2003 TOBT SEITE - GREATEST IN STORES NOVEMBER 9 www.americanradiohistory.com We're Scaling Back... Less Commercials, Less Station Promos and Even Shorter Breaks. We heard you...Clear Chancel Radio is working hard to give advertisers and their clients more of what they want -a great radio environment without the clutter. Less commercials and less promotional interruptions ecual better opportunities to effectively advertise on Clear Channel Radio stations. Ask your Clear Channel Radio Account Executive how you can advertise in the less cluttered, more valuable environment. Thank you for weighing in on this issue. CLEARCHANNEL 12ADI0 www.clearchannel.com www.americanradiohistory.com JULY 30, 2004 I N S I D E Radio Recovery Finally Underway? WHAT'S THE BIG IDEA? Clear Channel, Infinity see modest revenue gains Creative promotions are always in demand, By Joe Howard and this week's Management/Marketing/ For the company overall, rev- R &R Washinqton Bureau Sales section gives you more than 20 fun, jnowarow2dioandrecords. -

Wendy Williams Web Bio

Wendy Williams Web Bio Information Biography Biographical Statement Wendy M. Williams is Professor in the Department of Human Development at Cornell University, where she studies the development, assessment, training, and societal implications of intelligence. She holds Ph.D. and Master's degrees in psychology from Yale University, a Master's in physical anthropology from Yale, and a B.A. in English and biology from Columbia University, awarded cum laude with special distinction. In the fall of 2009, Williams founded (and now directs) the Cornell Institute for Women in Science (CIWS), a National Institutes of Health-funded research and outreach center that studies and promotes the careers of women scientists. She also heads "Thinking Like A Scientist," a national education-outreach program funded by the National Science Foundation, which is designed to encourage traditionally-underrepresented groups (girls, people of color, and people from disadvantaged backgrounds) to pursue science education and careers. In the past, Williams directed the joint Harvard-Yale Practical and Creative Intelligence for School Project, and was Co-Principal Investigator for a six-year, $1.4 million Army Research Institute grant to study practical intelligence and success at leadership. In addition to dozens of articles and chapters on her research, Williams has authored nine books and edited five volumes. They include The Reluctant Reader (sole authored), How to Develop Student Creativity (with Robert Sternberg), Escaping the Advice Trap (with Stephen Ceci; reviewed in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and USA Today), Practical Intelligence for School (with Howard Gardner, Robert Sternberg, Tina Blythe, Noel White, and Jin Li), Why Aren’t More Women in Science? (with Stephen Ceci; winner of a 2007 Independent Publisher Book Award), and The Mathematics of Sex (with Stephen Ceci).