1 Desperate Measures: Truman, Eisenhower, and the Lead-Up To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title of Thesis: ABSTRACT CLASSIFYING BIAS

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis Directed By: Dr. David Zajic, Ph.D. Our project extends previous algorithmic approaches to finding bias in large text corpora. We used multilingual topic modeling to examine language-specific bias in the English, Spanish, and Russian versions of Wikipedia. In particular, we placed Spanish articles discussing the Cold War on a Russian-English viewpoint spectrum based on similarity in topic distribution. We then crowdsourced human annotations of Spanish Wikipedia articles for comparison to the topic model. Our hypothesis was that human annotators and topic modeling algorithms would provide correlated results for bias. However, that was not the case. Our annotators indicated that humans were more perceptive of sentiment in article text than topic distribution, which suggests that our classifier provides a different perspective on a text’s bias. CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Gemstone Honors Program, University of Maryland, 2018 Advisory Committee: Dr. David Zajic, Chair Dr. Brian Butler Dr. Marine Carpuat Dr. Melanie Kill Dr. Philip Resnik Mr. Ed Summers © Copyright by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang 2018 Acknowledgements We would like to express our sincerest gratitude to our mentor, Dr. -

Conspiracy of Peace: the Cold War, the International Peace Movement, and the Soviet Peace Campaign, 1946-1956

The London School of Economics and Political Science Conspiracy of Peace: The Cold War, the International Peace Movement, and the Soviet Peace Campaign, 1946-1956 Vladimir Dobrenko A thesis submitted to the Department of International History of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, October 2015 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 90,957 words. Statement of conjoint work I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by John Clifton of www.proofreading247.co.uk/ I have followed the Chicago Manual of Style, 16th edition, for referencing. 2 Abstract This thesis deals with the Soviet Union’s Peace Campaign during the first decade of the Cold War as it sought to establish the Iron Curtain. The thesis focuses on the primary institutions engaged in the Peace Campaign: the World Peace Council and the Soviet Peace Committee. -

The Real 007 Used Fake News to Get the U.S. Into World War II About:Reader?Url=

The Real 007 Used Fake News to Get the U.S. into World War II about:reader?url=http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2017/01/29/the-r... thedailybeast.com Marc Wortman01.28.17 10:00 PM ET Photo Illustration by Elizabeth Brockway/The Daily Beast CLOAK & DAGGER The British ran a massive and illegal propaganda operation on American soil during World War II—and the White House helped. In the spring of 1940, British Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill was certain of one thing for his nation caught up in a fight to the death with Nazi Germany: Without American support his 1 of 11 3/20/2017 4:45 PM The Real 007 Used Fake News to Get the U.S. into World War II about:reader?url=http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2017/01/29/the-r... nation might not survive. But the vast majority of Americans—better than 80 percent by some polls—opposed joining the fight to stop Hitler. Many were even against sending any munitions, ships or weapons to the United Kingdom at all. To save his country, Churchill had not only to battle the Nazis in Europe, he had to win the war for public opinion among Americans. He knew just the man for the job. In May 1940, as defeated British forces were being pushed off the European continent at Dunkirk, Churchill dispatched a soft-spoken, forty-three-year-old Canadian multimillionaire entrepreneur to the United States. William Stephenson traveled under false diplomatic passport. MI6—the British secret intelligence service—directed Stephenson to establish himself as a liaison to American intelligence. -

The Historical Legacy for Contemporary Russian Foreign Policy

CHAPTER 1 The Historical Legacy for Contemporary Russian Foreign Policy o other country in the world is a global power simply by virtue of geogra- N phy.1 The growth of Russia from an isolated, backward East Slavic principal- ity into a continental Eurasian empire meant that Russian foreign policy had to engage with many of the world’s principal centers of power. A Russian official trying to chart the country’s foreign policy in the 18th century, for instance, would have to be concerned simultaneously about the position and actions of the Manchu Empire in China, the Persian and Ottoman Empires (and their respec- tive vassals and subordinate allies), as well as all of the Great Powers in Europe, including Austria, Prussia, France, Britain, Holland, and Sweden. This geographic reality laid the basis for a Russian tradition of a “multivector” foreign policy, with leaders, at different points, emphasizing the importance of rela- tions with different parts of the world. For instance, during the 17th century, fully half of the departments of the Posolskii Prikaz—the Ambassadors’ Office—of the Muscovite state dealt with Russia’s neighbors to the south and east; in the next cen- tury, three out of the four departments of the College of International Affairs (the successor agency in the imperial government) covered different regions of Europe.2 Russian history thus bequeaths to the current government a variety of options in terms of how to frame the country’s international orientation. To some extent, the choices open to Russia today are rooted in the legacies of past decisions. -

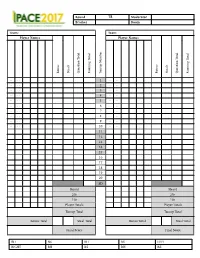

Round Moderator Bracket Room Team

Round 18 Moderator Bracket Room Team: Team: Player Names Player Names Steals Bonus Steals Question Total Running Total Bonus Running Total Tossup Number Question Total .. .. 1 .. .. .. .. 2 .. .. .. .. 3 .. .. .. .. 4 .. .. .. .. 5 .. .. .. .. 6 .. .. .. .. 7 .. .. .. .. 8 .. .. .. .. 9 .. .. .. .. 10 .. .. 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 SD Heard Heard 20s 20s 10s 10s Player Totals Player Totals Tossup Total Tossup Total Bonus Total Steal Total Bonus Total Steal Total Final Score Final Score RH RS BH BS LEFT RIGHT BH BS RH RS PACE NSC 2017 - Round 18 - Tossups 1. A small sculpture by this man depicts a winged putto with a faun's tail wearing what look like chaps, exposing his rear end and genitals. Padua's Piazza del Santo is home to a sculpture by this man in which one figure rests a hoof on a small sphere representing the world. His Atys is currently held in the Bargello along with his depiction of St. George, which like his St. Mark was originally sculpted for a niche of the (*) Orsanmichele. The equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius inspired this man's depiction of Erasmo da Narni. The central figure holds a large sword and rests his foot on a helmeted head in a sculpture by this artist that was the first freestanding male nude produced since antiquity. For 10 points, name this Florentine sculptor of Gattamelata and that bronze David. ANSWER: Donatello [or Donatello Niccolò di Betto Bardi] <Carson> 2. Minnesota Congressman John T. Bernard cast the only dissenting vote against a law banning US intervention in this conflict. Torkild Rieber of Texaco supplied massive quantities of oil to the winning side in this war. -

Death of Stalin’ Almost a Soviet Spin on ‘Veep’

CHICAGOLAWBULLETIN.COM FRIDAY, MARCH 30, 2018 ® Volume 164, No. 63 Serving Chicago’s legal community for 163 years ‘Death of Stalin’ almost a Soviet spin on ‘Veep’ inutes before a which was not as strongly word - Stalin, Beria was keeper and cre - live-broadcast ed as in the movie. ator of Stalin’s lists of those to be Mozart concerto is There was a late-night orches - tortured, exiled or sent to the gu - about to end, the tra round-up; Stalin did lay dying lags. He was a genius at mass ex - Radio Moscow sta - on the floor for hours because his ecution, ghastly humiliation and Mtion manager receives a telephone guards were too fearful to enter perverse sexual exploitation. call from the office of Supreme his room after hearing him fall; REBECCA Iannucci says he began Commander Josef Stal in. The and the Politburo members de - mulling a movie idea about a fic - premier loved the performance, liberated at length whether to L. F ORD tional contemporary dictator says the voice on the other end of call a doctor as Stalin expired, after ending his four-year run as the line, and requests that a fearing the consequences of call - the creator of the Emmy Award- recording of the concert be sent ing the “wrong” doctor. Rebecca L. Ford is counsel at Scharf winning HBO series “Veep.” to him immedi ately. Writer and director Armando Banks Marmor LLC, and concentrates While pondering this prospect, There’s a problem. The con - Iannucci didn’t ask the American her practice on complex litigation, he was given a copy of Fabien cert wasn’t recorded. -

On Stalin's Team

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION When Stalin wanted to temporize in dealing with foreigners, he sometimes indicated that the problem would be getting it past his Polit- buro. This was taken as a fiction, since the diplomats assumed, correctly, that the final decision was his. But that doesn’t mean that there wasn’t a Polit buro that he consulted or a team of colleagues he worked with. That team—about a dozen persons at any given time, all men—came into ex- istence in the 1920s, fought the Opposition teams headed by Lev Trotsky and Grigory Zinoviev after Lenin’s death, and stayed together, remark- ably, for three decades, showing a phoenixlike capacity to survive team- threatening situations like the Great Purges, the paranoia of Stalin’s last years, and the perils of the post- Stalin transition. Thirty years is a long time to stay together in politics, even in a less lethal political climate than that of the Soviet Union under Stalin. The team finally disbanded in 1957, when one member (Nikita Khrushchev) made himself the new top boss and got rid of the rest of them. I’ve used the term “team” (in Russian, komanda) for the leadership group around Stalin. At least one other scholar has also used this term, but alternatives are available. You could call it a “gang” (shaika) if you wanted to claim that its activities—ruling the country—had an illegiti- mate quality that made them essentially criminal rather than govern- mental. -

The Methods of Stalinism Condemned at the Soviet Communist Party Congress' from Il Nuovo Corriere Della Sera (18 February 1956)

'The methods of Stalinism condemned at the Soviet Communist Party Congress' from Il nuovo Corriere della Sera (18 February 1956) Caption: On 18 February 1956, the Italian newspaper Il nuovo Corriere della Sera speculates on the genuine desire for de-Stalinisation shown by Nikita Khrushchev, the new Soviet leader, on the occasion of his submission of the report on Stalin’s crimes to the 20th Soviet Communist Party Congress in Moscow. Source: Il nuovo Corriere della Sera. 18.02.1956, n° 42; anno 81. Milano: Corriere della Sera. "Il congresso del P.C. sovietico condanna i metodi dello stalinismo", auteur:Ottone, Piero , p. 1. Copyright: (c) Translation CVCE.EU by UNI.LU All rights of reproduction, of public communication, of adaptation, of distribution or of dissemination via Internet, internal network or any other means are strictly reserved in all countries. Consult the legal notice and the terms and conditions of use regarding this site. URL: http://www.cvce.eu/obj/the_methods_of_stalinism_condemned_at_the_soviet_com munist_party_congress_from_il_nuovo_corriere_della_sera_18_february_1956-en- d21f39be-519c-497f-9082-49193e08afc6.html Last updated: 05/07/2016 1/3 The methods of Stalinism condemned at the Soviet Communist Party Congress ‘The personality cult, widespread in the past,’ says Suslov, ‘has wrought serious damage’ — Malenkov confirms the principles of collective direction — In a speech, Togliatti endorses Khrushchev’s guidelines on tactics in the ‘capitalist’ countries From our correspondent Moscow 17 February, evening. The Soviet Party Congress has reached its fourth day; mile-long speeches, stuffed with learned citations from Marx and Lenin, have followed one another without respite. Speakers are commenting on Khrushchev’s report or, to be more precise, are praising and paraphrasing it. -

The Golunov Affair

the harriman institute at columbia university FALL 2019 The Golunov Affair Fighting Corruption in Russia Harriman Magazine is published biannually by Design and Art Direction: Columbia Creative Opposite page: the Harriman Institute. Alexander Cooley Harriman Institute (Photo by Jeffrey Managing Editor: Ronald Meyer Alexander Cooley, Director Schifman) Editor: Masha Udensiva-Brenner Alla Rachkov, Associate Director Ryan Kreider, Assistant Director Comments, suggestions, or address changes may Rebecca Dalton, Program Manager, Student Affairs be emailed to Masha Udensiva-Brenner at [email protected]. Harriman Institute Columbia University Cover image: Police officer walks past a “lone picket” 420 West 118th Street standing in front of the Main Office of the Moscow Police, New York, NY 10027 holding a sign that reads: “I am Golunov” (June 7, 2019). ITAR-TASS News Agency/Alamy Live News. Tel: 212-854-4623 Fax: 212-666-3481 Image on this page: Eduard Gorokhovsky, Untitled, 1988. Watercolor on paper, 21½ x 29½ in. Courtesy of the Kolodzei Collection of Russian and Eastern European Art, For the latest news and updates about the Harriman Kolodzei Art Foundation. www.KolodzeiArt.org Institute, visit harriman.columbia.edu. Stay connected through Facebook and Twitter! www.twitter.com/HarrimanInst www.facebook.com/TheHarrimanInstitute FROM THE DIRECTOR he June arrest of investigative journalist Ivan Golunov, the powerful civic T movement in his support, and his subsequent release marked the start of an eventful summer in Russia. In mid-July, Russians took to the streets again, over the disqualification of opposition candidates from the Moscow City Duma election. In this context, we dedicate the bulk of this issue to contemporary Russia. -

The Treason of Rockefeller Standard Oil (Exxon) During World War II

The Treason Of Rockefeller Standard Oil (Exxon) During World War II By The American Chronicle February 4, 2012 We have reported on Wall Street’s financing of Hitler and Nazi programs prior to World War 2 but we have not given as much attention to its treasonous acts during the war. The depths to which these men of fabled wealth sent Americans to their deaths is one of the great untold stories of the war. John Rockefeller, Jr. appointed William Farish chairman of Standard Oil of New Jersey which was later rechristened Exxon. Farish lead a close partnership with his company and I. G. Farben, the German pharmaceutical giant whose primary raison d'etre was to occlude ownership of assets and financial transactions between the two companies, especially in the event of war between the companies' respective nations. This combine opened the Auschwitz prison camp on June 14, 1940 to produce artificial rubber and gasoline from coal using proprietary patents rights granted by Standard. Standard Oil and I. G. Farben provided the capital and technology while Hitler supplied the labor consisting of political enemies and Jews. Standard withheld these patents from US military and industry but supplied them freely to the Nazis. Farish plead “no contest” to criminal conspiracy with the Nazis. A term of the plea stipulated that Standard would provide the US government the patent rights to produce artificial rubber from Standard technology while Farish paid a nominal 5,000 USD fine Frank Howard, a vice president at Standard Oil NJ, wrote Farish shortly after war broke out in Europe that he had renewed the business relationship described above with Farben using Royal Dutch Shell mediation top provide an additional layer of opacity. -

Cómo Citar El Artículo Número Completo Más Información Del

Revista de Economía Institucional ISSN: 0124-5996 Universidad Externado de Colombia Braden, Spruille EL EMBAJADOR SPRUILLE BRADEN EN COLOMBIA, 1939-1941 Revista de Economía Institucional, vol. 19, núm. 37, 2017, Julio-Diciembre, pp. 265-313 Universidad Externado de Colombia DOI: https://doi.org/10.18601/01245996.v19n37.13 Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=41956426013 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Redalyc Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto EL EMBAJADOR SPRUILLE BRADEN EN COLOMBIA, 1939-1941 Spruille Braden* * * * pruille Braden (1894-1978) fue embajador en Colombia entre 1939 y 1942, durante la presidencia de Eduardo Santos. Aprendió el español desdeS niño y conocía bien la cultura latinoamericana. Nació en Elkhor, Montana, pero pasó su infancia en una mina de cobre chilena, de pro- piedad de su padre, ingeniero de grandes dotes empresariales. Regresó a Estados Unidos para cursar su enseñanza secundaria. Estudió en la Universidad de Yale donde, siguiendo el ejemplo paterno, se graduó como ingeniero de minas. Regresó a Chile, trabajó con su padre en proyectos mineros y se casó con una chilena de clase alta. Durante su estadía sura- mericana no descuidó los vínculos políticos con Washington. Participó en la Conferencia de Paz del Chaco, realizada en Buenos Aires (1935-1936), y pasó al mundo de la diplomacia estadounidense, con embajadas en Colombia y en Cuba (1942-1945), donde estrechó lazos con el dictador Fulgencio Batista. -

Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler

TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Introduction Unexplored Facets of Naziism PART ONE: Wall Street Builds Nazi Industry Chapter One Wall Street Paves the Way for Hitler 1924: The Dawes Plan 1928: The Young Plan B.I.S. — The Apex of Control Building the German Cartels Chapter Two The Empire of I.G. Farben The Economic Power of I.G. Farben Polishing I.G. Farben's Image The American I.G. Farben Chapter Three General Electric Funds Hitler General Electric in Weimar, Germany General Electric & the Financing of Hitler Technical Cooperation with Krupp A.E.G. Avoids the Bombs in World War II Chapter Four Standard Oil Duels World War II Ethyl Lead for the Wehrmacht Standard Oil and Synthetic Rubber The Deutsche-Amerikanische Petroleum A.G. Chapter Five I.T.T. Works Both Sides of the War Baron Kurt von Schröder and I.T.T. Westrick, Texaco, and I.T.T. I.T.T. in Wartime Germany PART TWO: Wall Street and Funds for Hitler Chapter Six Henry Ford and the Nazis Henry Ford: Hitler's First Foreign Banker Henry Ford Receives a Nazi Medal Ford Assists the German War Effort Chapter Seven Who Financed Adolf Hitler? Some Early Hitler Backers Fritz Thyssen and W.A. Harriman Company Financing Hitler in the March 1933 Elections The 1933 Political Contributions Chapter Eight Putzi: Friend of Hitler and Roosevelt Putzi's Role in the Reichstag Fire Roosevelt's New Deal and Hitler's New Order Chapter Nine Wall Street and the Nazi Inner Circle The S.S. Circle of Friends I.G. Farben and the Keppler Circle Wall Street and the S.S.