Benjamin, “Paris — Capital of the Nineteenth Century”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taming the Bourgeoisie: Grandville's Scènes De La Vie Privée Et Publique

EnterText 7.3 KERI BERG Taming the Bourgeoisie: Grandville’s Scènes de la vie privée et publique des animaux (1840-1842) Writing in 1842, an unnamed critic for L’Artiste described the caricaturist J. J. Grandville’s (1803-1847) Scènes de la vie privée et publique des animaux as a “mirror, accurate but not very flattering, in which each of us can look at ourselves and recognize ourselves.”1 The critic’s description of the illustrated book Scènes de la vie privée et publique des animaux (henceforth referred to as Les Animaux) sums up both the work and its particular mode of representation: caricature, which is the comic distortion and/or exaggeration of an original object. From political celebrations to marriage proposals, Les Animaux’s visual and verbal “scènes” from nineteenth- century life presented period readers with a deformed image of themselves, their personality traits, habits and hobbies distorted by the artist’s pencil. Grandville’s brand of caricature, however, stands out from that of his contemporaries, such as Honoré Daumier, Henri Monnier and Gavarni, in that the basis for Les Animaux’s distortion, as the title of the work suggests, is the animal. In Les Animaux, the bourgeois banker is a fattened turkey, the politician a rotund hippopotamus and the landlord a beady-eyed vulture. While the use of animal imagery and metaphors was not new in the 1840s, Grandville’s approach was, as the caricaturist created Keri Berg: Taming the Bourgeoisie 43 EnterText 7.3 hybrid creatures—animal heads atop human bodies—that visually and literally metamorphosed the person figured. -

1 DOUBLE DÉTENTE the Role of Gaullist France and Maoist China In

DOUBLE DÉTENTE The Role of Gaullist France and Maoist China in the Formation of Cold War Détente, 1954-1973 by Alice Siqi Han A thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors Harvard University Cambridge Massachusetts 10 March 2016 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: Détente in Three Parts: The France-China-U.S. Triangle ........................................ 3 1. From Paris to Pékin .................................................................................................................. 17 2. “Opening” the China Box ......................................................................................................... 47 3. The Nixon Administration’s Search for Détente ...................................................................... 82 Conclusion: The Case for Diplomacy ......................................................................................... 113 Works Cited ................................................................................................................................ 122 2 Introduction Détente in Three Parts: The France-China-U.S. Triangle Did the historic “opening to China” during the Cold War start with the French? Conventional Cold War history portrays President Richard Nixon and his chief national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, as the principal architects of the U.S. “opening to China.”1 Part of the Nixon administration’s détente strategy, the China initiative began in 1971 with Kissinger’s -

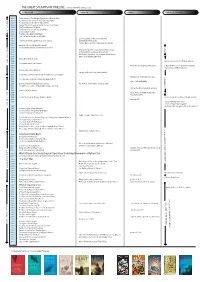

Download the Timeline and Follow Along

THE GREAT STEAMPUNK TIMELINE (to be printed A3 portrait size) LITERATURE FILM & TV GAMES PARALLEL TRACKS 1818 - Frankenstein: or The Modern Prometheus (Mary Shelley) 1864 - A Journey to the Centre of the Earth (Jules Verne) K N 1865 - From the Earth to the Moon (Jules Verne) U P 1869 - Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Jules Verne) - O 1895 - The Time Machine (HG Wells) T O 1896 - The Island of Doctor Moreau (HG Wells) R P 1897 - Dracula (Bram Stoker) 1898 - The War of the Worlds (HG Wells) 1901 - The First Men in the Moon (HG Wells) 1954 - 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Disney) 1965 - The Wolves of Willoughby Chase (Joan Aiken) The Wild Wild West (CBS) 1969 - Captain Nemo and the Underwater City (MGM) 1971 - Warlord of the Air (Michael Moorcock) 1973 - A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! (Harry Harrison) K E N G 1975 - The Land That Time Forgot (Amicus Productions) U A 1976 - At the Earth's Core (Amicus Productions) P S S 1977 - The People That Time Forgot (Amicus Productions) A R 1978 - Warlords of Atlantis (EMI Films) B Y 1979 - Morlock Night (K. W. Jeter) L R 1982 - Burning Chrome, Omni (William Gibson) A E 1983 - The Anubis Gates (Tim Powers) 1983 - Warhammer Fantasy tabletop game > Bruce Bethke coins 'Cyberpunk' (Amazing) 1984 - Neuromancer (William Gibson) 1986 - Homunculus (James Blaylock) 1986 - Laputa Castle in the Sky (Studio Ghibli) 1987 - > K. W. Jeter coins term 'steampunk' in a letter to Locus magazine -

When Richard Nixon Took Office As President of the United

TThrace hFrenctenbergh Factor in U.S. Foreign Policy, 1969–1974 The French Factor in U.S. Foreign Policy during the Nixon-Pompidou Period, 1969–1974 ✣ Marc Trachtenberg When Richard Nixon took ofªce as president of the United States in early 1969, he and his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, wanted to put U.S. relations with France on an entirely new footing. Ties be- tween the two countries in the 1960s, especially from early 1963 on, had been far from ideal, and U.S. ofªcials at the time blamed French President Charles de Gaulle for the fact that the United States was on such poor terms with its old ally. But Nixon and Kissinger took a rather different view. They admired de Gaulle and even thought of themselves as Gaullists.1 Like de Gaulle, they believed that the United States in the past had been too domineering. “The excessive concentration of decision-making in the hands of the senior part- ner,” as Kissinger put it in a book published in 1965, was not in America’s own interest; it drained the alliance of “long-term political vitality.”2 The United States needed real allies—“self-conªdent partners with a strongly de- veloped sense of identity”—and not satellites.3 Nixon took the same line in meetings both with de Gaulle in March 1969 and with his successor as presi- dent, Georges Pompidou, in February 1970. “To have just two superpowers,” 1. See, for example, Nixon-Pompidou Meeting, 31 May 1973, 10 a.m., p. 3, in Kissinger Transcripts Collection, Doc. -

Visualizing Fantastika

An Interdisciplinary Conference Friday, 4th July 2014, Lancaster University Lancaster University’s department of English and Creative Writing invites proposals for an interdisciplinary conference: Visualizing Fantastika. Fantastika, coined by John Clute, is an umbrella term which incorporates the genres of fantasy, science fiction, and horror, but can also include alternative histories, steampunk, young adult fiction, or any other imaginative space. The conference wishes to consider the visual possibilities of the fantastic in a wide range of arts and media, which may include, but is not limited to: graphic novels, film, illustrations, games, and other visual media. Some suggested topics are: - Visual conventions in cinema and illustration that are particular to a specific genre - Visuals codes in cinema and illustration that aid in interpreting story (such as mood, character, plot) - Adaptations and crossovers between different media - The effect of the development of technology on visual style - The visual style of fantastika as a product of its culture and time - Imagery evoked by non-visual codes (such as music and language) We are very pleased to announce Bryan Talbot and Brian Baker as our keynote speakers. Bryan Talbot is most famously known for The Adventures of Luther Arkwright and Alice in Sunderland. He will be delivering a talk on his graphic novel Grandville. Dr. Brian Baker is a Lecturer at Lancaster University. Among other research interests, he has published Masculinity in Fiction and Film, and has edited a collection of essays on screen adaptations of literature. We are delighted to invite both speakers to our conference. We are extending our abstract deadline until March 30th. -

Grandville Mon Amour Ebook, Epub

GRANDVILLE MON AMOUR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Bryan Talbot | 108 pages | 30 Nov 2010 | Dark Horse Comics,U.S. | 9781595825742 | English | Milwaukie, United States Grandville Mon Amour PDF Book Rowland Emett machine. During their investigation they uncover a political conspiracy to start a new war between Britain and France. If you like subversive plots like V for Vendetta , you should appreciate Grandville. As the male protagonist anyone he sleeps with is by default the love of his life, more so if they die because of him. With his customary tenacity, LeBrock stalks his prey through a world populated by anthropomorphic animals, an underclass of humans and automaton robots where advanced steam technology powers everything from hansom cabs to iron flying machines. Add to Wishlist. Weitere Hilfe gibt es auf der "Wissenswertes"-Hilfe-Seite. The books contain references to other works, such as The Adventures of Tintin. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. Brian Wood concludes the series leading into EVE: Valkyrie-a groundbreaking virtual-reality space dogfighting shooter from Dec 27, Ross Kitson rated it it was amazing. In fact if there is any justice it should bring in new fans of the whole anthropomorphic genre too. Buy the Heart of Empire Directors Cut. Follow the badger! The Grandville Annotations Go to any of the Grandville annotations pages:. Site created and maintained by James Robertson: online marketing expert. Given, it was because of him, and perhaps the trauma made her seem more important to him, but the book makes her seem like the love of his life and, come on. -

Review of Claire Nally's Steampunk

The Perks and Pitfalls of Parody: Review of Claire Nally’s Steampunk: Gender, Sub-Culture and the Neo-Victorian Helena Esser (Birkbeck, University of London, England, UK) Claire Nally, Steampunk: Gender, Sub-Culture and the Neo-Victorian London: Bloomsbury, 2019 ISBN: 978-1350113183, £85 (HB) ***** Claire Nally’s Steampunk: Gender, Sub-Culture, and the Neo-Victorian is the first full-length study to consider steampunk through a lens of neo- Victorian critique. A neo-Victorian perspective on steampunk has of course been well established in and through this journal since Rebecca Onion’s 2008 article in its inaugural issue, a 2010 special issue of Neo-Victorian Studies dedicated to the subject and guest edited by Rachel Bowser and Brian Croxall, and several subsequent articles (see, e.g., Montz 2011, Ferguson 2011, Danahay 2016a and 2016b, Pho 2019). Three anthologies have further interrogated a wide range of aspects in steampunk’s imaginative fiction and subculture, often focused on its creative re-use of technology and subcultural politics, but also including colonial frontiers, urbanism, gender and femininity, race and disability, consumerism, and identity (see Taddeo and Miller 2013, Brummett 2014, Bowser and Croxall 2016). James Carrott and Brian Johnson’s non-fiction Vintage Tomorrows (2013) and concomitant documentary (2015, Samuel Goldwyn Films) have explored and documented steampunk subculture in the US, and Brandy Schillace’s Clockwork Futures (2017) illustrates the history of the technology integral to the steampunk imagination. Meanwhile Roger Whitson’s Steampunk and Nineteenth-Century Digital Humanities (2016) is dedicated to steampunk’s material culture in the context of digital humanities. -

Barry Trotter Done Gone: the Perils of Publishing Parody,” Which Was Held at the 2002 ALA Annual Conference, in Atlanta, Georgia, on June 17

ISSN 0028-9485 November 2002 Vol. LI No. 6 Following are edited speeches from the program “Barry Trotter Done Gone: The Perils of Publishing Parody,” which was held at the 2002 ALA Annual Conference, in Atlanta, Georgia, on June 17. introductory remarks by Margo Crist Good afternoon, and welcome to our program “Barry Trotter Done Gone: The Perils of Publishing Parody.” I am Margo Crist, chair of the ALA’s Intellectual Freedom Committee. We are pleased to present this program in conjunction with the Association of American Publishers and the American Booksellers Foundation For Free Expression. I’d “Barry Trotter like to take a moment to introduce our co-sponsors. Judith Platt is Director of AAP’s Freedom to Read Program and Chris Finan is President of the American Booksellers done gone”: Foundation for Free Experssion. Our distinguished panel this afternoon is made up of Michael Gerber, Bruce Rich, and Wendy Strothman, who will discuss the art of parody, the legal issues and publishing deci- perils of sions involved in publishing parody, and how the publication—and challenge to—The Wind Done Gone have affected the publishing environment. publishing Michael Gerber, author of Barry Trotter and the Unauthorized Parody, will begin by providing a history and framework for our discussion. Michael is a life-long humorist and has been widely published with commentaries and humor appearing in The New Yorker, parody The Atlantic Monthly, Esquire, The Wall Street Journal, and numerous other publications. He also has written for PBS, NPR and Saturday Night Live. While at Yale University, where he graduated in 1991 in history, Michael resurrected The Yale Record, America’s oldest college humor magazine. -

SBR December 09.Indd

VOLUME 2, ISSUE 4 Sacramento FREE Book Review NEW AND OF INTEREST Under the Dome A psychology experiment run by Stephen King 6 Page 2 Th e Atlantis Revelation World-saving astrologer Page 4 John Dies at the End Comedic high-octane nightmare fuel 11 Page 7 Following Yonder Star By Jane Yolen Gift Guide Key Porter Books, $16.95, 24 pages Page 13 Jane Yolen is considered a modern-day (fi fty-fi ve in all, if my addition skills haven’t Hans Christian Andersen, with dozens of abandoned me, across a crowded two-page Extreme Cuisine books to her name as both an author and an spread) highlights both the multitude of Bon appetit, if you dare! anthology editor. (Even Wikipedia is reluc- those aff ected and the magnitude of the Page 26 tant to compile a complete list of her literary event itself. works.) Fantasy and folklore are her most And trust me, all fi fty-fi ve are accounted recognized fi elds of stylistic expertise, but for, as I confi rmed with a brief and mildly Green Metropolis she has also contributed a great deal to the frustrating Where’s Waldo?-esque exercise 20 children’s section of the library, and it’s here of identifying each of the players featured. Go green gone wild that you’d most likely fi nd her latest eff ort, Th e closing image of the animals and Page 27 Under the Star: A Christmas Counting Story. people all gazing with wonder into the tiny With Vlasta Van Kampen’s simple illus- ramshackle manger, as two new parents trations vividly enhanced by a rich, vibrant look down upon their newborn, is an im- Ace of Cakes palette, Yolen seamlessly meshes a simple pressive one, both in scale and execution. -

Neo-Imperial Anxieties in Postcolonial

LETTING OFF STEAM: NEO-IMPERIAL ANXIETIES IN POSTCOLONIAL STEAMPUNK LITERATURE, AESTHETICS, AND PERFORMANCE _______________________________________ a thesis presented to the faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri - Columbia _______________________________________ in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts ______________________________________ by RACHEL COCHRAN Dr. Karen Piper, thesis supervisor MAY 2014 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled LETTING OFF STEAM: NEO-IMPERIAL ANXIETIES IN POSTCOLONIAL STEAMPUNK LITERATURE, AESTHETICS, AND PERFORMANCE presented by Rachel Cochran, a candidate for the degree of master of arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Karen Piper Professor Rebecca Dingo Professor Julie Elman ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Karen Piper for her encouragement and guidance. Studying postcolonial theory with her has regularly driven me to challenge my assumptions, and this thesis is the result of all of my paradigms shifting. Drs. Rebecca Dingo and Julie Elman also supplied passionate and engaged feedback that has been instrumental in my completion of this project. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ii List of Illustrations iv Introduction. Defining and Situating Steampunk as a Postcolonial Phenomenon 1 Fractured Timelines and Neocolonial Retrofutures 3 Chapter 1. Alternate Intertextualities: Narrative Colonizing in Steampunk Literature 9 Reanimating Monster Narratives 14 Chapter 2. “Cogs, Clocks, and Kraken”: The Aesthetic Symbology of Steampunk 22 The Postcolonial Racial Politics of Brown 23 Cephalopods and Machines 27 Progress, Cogs, and Clockwork 31 Rust and the Abandoned Factory 35 Chapter 3. DIY Fashion and Identity Performance 37 Identity Performance and Personae 40 Mechanical Bodies 47 Conclusion: Pressure Valves 51 Bibliography 54 iii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. -

Child Care Homes and Centers Bureau of Community and Health Systems Provider Directory

Michigan Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs, Child Care Homes and Centers Bureau of Community and Health Systems Provider Directory PROVIDER NAME ADDRESS CITY, STATE, ZIP CODE COUNTY 100 Acre Wood Daycare Center 1340 Onondaga Rd. Holt MI 48842 Ingham 123 Grow With Me 451 Helen St Brooklyn MI 49230 Jackson 1st Advantage Learning Center 26555 John R Road Madison Heights MI 48071 Oakland 2 Day's Child Learning Center 15075 Meyers Detroit MI 48227 Wayne 2 Sweets Angels Family Daycare 9701 Everts Street Detroit MI 48224 Wayne 21st Century - Milwood Magnet 2916 Konkle Kalamazoo MI 49001 Kalamazoo 21st Century/KCIS - Hillside Middle School 1941 Alamo Ave. Kalamazoo MI 49006 Kalamazoo 21st Century/KCIS - Linden Grove Middle School 4241 Arboretum Pkwy. Kalamazoo MI 49006 Kalamazoo 21st Century/KCIS - Maple Street Magnet 922 W. Maple St. Kalamazoo MI 49008 Kalamazoo 2BKids Creative Station 622 Bates St Grand Rapids MI 49503 Kent 3 C's & ABC 47080 Exeter Ct Shelby Twp MI 48315 Macomb 3 Musketeers Daycare 1388 Lancaster Ave NW Grand Rapids MI 49504 Kent 4 K Learning Center 13220 Greenfield Detroit MI 48227 Wayne 40 Acre Wood Daycare 5595 Truckey Rd Alpena MI 49707 Alpena A & J's Child Care 512 W Martin St Gladwin MI 48624 Gladwin A and W Day Care Center 6565 Greenfield Detroit MI 48228 Wayne A Brighter Beginning 16101 Schoolcraft Detroit MI 48227 Wayne A Child's World Learning Center 1828 E Michigan Ave Ypsilanti MI 48198 Washtenaw A G B U Alex & Marie Manoogian School 22001 Northwestern Southfield MI 48075 Oakland A Growing Place Inc 40700 Ten Mile Road Novi MI 48375 Oakland A Happy Place Childcare 3713 Lawndale Drive Midland MI 48642 Midland A Home Away From Home Child Care 3875 Bacon Ave Berkley MI 48072 Oakland A Joyful Noise Child Development Center LLC 2515 Ashman St. -

France and the Struggle to Overcome the Cold War Order, 1963-1968

Untying the Gaullian Knot: France and the Struggle to Overcome the Cold War Order, 1963-1968 Garret Joseph Martin London School of Economics and Political Science PhD International History / UMI Number: U221606 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U221606 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract On 14 January 1963, French President General Charles de Gaulle shook the Western world. During a press conference, he announced that France was not only vetoing the British application to join the European Economic Community, but that it was also rejecting US President John F. Kennedy’s proposal to integrate the French nuclear force defrappe into the Multilateral Force. In the aftermath of the Algerian War, De Gaulle’s spectacular double non was meant to signal the shift to a more ambitious diplomatic agenda, which centred on the twin aims of recapturing France’s Great Power status, and striving to overcome the Cold War bipolar order. In the next five years, France placed itself at the forefront of international affairs through a series of bold initiatives that affected all areas of the world.