Review of Claire Nally's Steampunk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Commodification of Whitby Goth Weekend and the Loss of a Subculture

View metadata, citation and similarbrought COREpapers to youat core.ac.ukby provided by Leeds Beckett Repository The Strange and Spooky Battle over Bats and Black Dresses: The Commodification of Whitby Goth Weekend and the Loss of a Subculture Professor Karl Spracklen (Leeds Metropolitan University, UK) and Beverley Spracklen (Independent Scholar) Lead Author Contact Details: Professor Karl Spracklen Carnegie Faculty Leeds Metropolitan University Cavendish Hall Headingley Campus Leeds LS6 3QU 44 (0)113 812 3608 [email protected] Abstract From counter culture to subculture to the ubiquity of every black-clad wannabe vampire hanging around the centre of Western cities, Goth has transcended a musical style to become a part of everyday leisure and popular culture. The music’s cultural terrain has been extensively mapped in the first decade of this century. In this paper we examine the phenomenon of the Whitby Goth Weekend, a modern Goth music festival, which has contributed to (and has been altered by) the heritage tourism marketing of Whitby as the holiday resort of Dracula (the place where Bram Stoker imagined the Vampire Count arriving one dark and stormy night). We examine marketing literature and websites that sell Whitby as a spooky town, and suggest that this strategy has driven the success of the Goth festival. We explore the development of the festival and the politics of its ownership, and its increasing visibility as a mainstream tourist destination for those who want to dress up for the weekend. By interviewing Goths from the north of England, we suggest that the mainstreaming of the festival has led to it becoming less attractive to those more established, older Goths who see the subculture’s authenticity as being rooted in the post-punk era, and who believe Goth subculture should be something one lives full-time. -

The Music (And More) 2019 Quarter 3 Report

The Music (and More) 2019 Quarter 3 Report Report covers the time period of July 1st to Kieran Robbins & Chief - "Sway" [glam rock] September 30th, 2019. I inadvertently missed Troy a few before that time period, which were brought to my attention by fans, bands & Moriah Formica - "I Don't Care What You others. The missing are listed at the end, along with an Think" (single) [hard rock] Albany End Note… Nine Votes Short - "NVS: 09/03/2019" [punk rock] RECORDINGS: Albany Hard Rock / Metal / Punk Psychomanteum - "Mortal Extremis" (single track) Attica - "Resurected" (EP) [hardcore metal] Albany [thrash prog metal industrial] Albany Between Now and Forever - "Happy" (single - Silversyde - "In The Dark" [christian gospel hard rock] Mudvayne cover) [melodic metal rock] Albany Troy/Toledo OH Black Electric - "Black Electric" [heavy stoner blues rock] Scotchka - "Back on the Liquor" | "Save" (single tracks) Voorheesville [emo pop punk] Albany Blood Blood Blood - "Stranglers” (single) [darkwave Somewhere To Call Home - "Somewhere To Call Home" horror synthpunk] Troy [nu-metalcore] Albany Broken Field Runner – "Lay My Head Down" [emo pop Untaymed - "Lady" (single track) [british hard rock] punk] Albany / LA Colonie Brookline - "Live From the Bunker - Acoustic" (EP) We’re History - "We’re History" | "Pop Tarts" - [acoustic pop-punk alt rock] Greenwich "Avalanche" (singles) [punk rock pop] Saratoga Springs Candy Ambulance - "Traumantic" [alternative grunge Wet Specimens - "Haunted Flesh" (EP) [hardcore punk] rock] Saratoga Springs Albany Craig Relyea - "Between the Rain" (single track) Rock / Pop [modern post-rock] Schenectady Achille - "Superman (A Song for Mora)" (single) [alternative pop rock] Albany Dead-Lift - "Take It or Leave It" (single) [metal hard rock fusion] Schenectady Caramel Snow - "Wheels Are Meant To Roll Away" (single track) [shoegaze dreampop] Delmar Deep Slut - "u up?" (3-song) [punk slutcore rap] Albany Cassandra Kubinski - "DREAMS (feat. -

New Music As Subculture Que Devient L’Avant-Garde ? La Nouvelle Musique Comme Sous-Culture Martin Iddon

Document generated on 09/29/2021 10:50 a.m. Circuit Musiques contemporaines What Becomes of the Avant-Guarded? New Music as Subculture Que devient l’avant-garde ? La nouvelle musique comme sous-culture Martin Iddon Pactes faustiens : l’hybridation des genres musicaux après Romitelli Article abstract Volume 24, Number 3, 2014 In a short ‘vox pop,’ written for Circuit in 2010, on the subject of the ‘future’ of new music, I proposed that new music — or the version of it tightly URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1027610ar intertwined with what was once thought of as the international avant-garde, at DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1027610ar any rate — might today be better thought of as a sort of subculture, akin to the spectacular subcultures of goth and punk, but radically different in that they See table of contents developed from the ‘grassroots,’ as it were, while new music comes from a position of extreme cultural privilege, which is to say it has access, even now, to modes of funding and infrastructure subcultures ‘proper’ never have. This essay develops this line of enquiry, outlining theories of subculture and Publisher(s) post-subculture — drawing on ‘classic’ and more recent research, from Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal Hebdige and Cohen to Hodkinson, Maffesoli, and Thornton — before presenting the, here more detailed, case that new music represents a sort of subculture, before making some tentative proposals regarding what sort of ISSN subculture it is and what this might mean for contemporary understandings of 1183-1693 (print) new music and what it is for. -

Psychobilly Psychosis and the Garage Disease in Athens

IAFOR Journal of Cultural Studies Volume 5 – Issue 1 – Spring 2020 Psychobilly Psychosis and the Garage Disease in Athens Michael Tsangaris, University of Piraeus, Greece Konstantina Agrafioti, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece Abstract The complexity and the bizarre nature of Psychobilly as a music genre and as a music collectivity make it very convenient for reconsidering several views in relation to subcultures, neo-tribes and scenes. More specifically, the case of Greek Psychobilly can categorically present how subcultural trends can be disseminated across gender, social classes and national borders. This study aims to trace historically the scene of Psychobilly in Athens based on typical ethnographic research and analytic autoethnography. The research question is: Which are the necessary elements that can determine the existence of a local music scene? Supported by semi-structured interviews, the study examines how individuals related to the Psychobilly subculture comprehend what constitutes the Greek Psychobilly scene. Although it can be questionable whether there ever was a Psychobilly scene in Athens, there were always small circles in existence into which people drifted and stayed for quite a while, constituting the pure core of the Greek Psychobilly subculture. Keywords: psychobilly, music genres, Athens, Post-subcultural Theory 31 IAFOR Journal of Cultural Studies Volume 5 – Issue 1 – Spring 2020 Introduction According to the American Countercultures Encyclopaedia, Psychobilly is a subculture that emerged in the 1980s from the unlikely combination of rockabilly and punk rock. The provocative and sometimes outrageous style associated with psychobillies (also known as “psychos”) mixes the blue-collar rawness and rebellion of 1950s rockabilly with the confrontational do-it-yourself style of 1970s punk rock, a syncretism infused with themes from monster and horror films, campy sci-fi movies, and even professional wrestling” (Wojcik, 2013, p. -

23. Wave-Gotik-Treffen

23. Wave-Gotik-Treffen - Termin: 6. - 9. Juni 2014 - Ort: Leipzig (an rund 40 Veranstaltungsorten über die ganz Stadt verteilt), Zeltplatz und Hauptveranstaltungsort am Stadtrand auf dem agra-Messegelände Markkleeberg - Internetseiten: www.wave-gotik-treffen.de www.facebook.com/WaveGotikTreffen - Musikrichtungen: alle Arten von dunkler Musik: Gothic; EBM; Industrial; Dark Ambient; Apocalyptic Folk; Post Punk, Synthpop etc. - Eintrittskarten: 4-Tageskarte für alle Veranstaltungen im Rahmen des 23. Wave-Gotik-Treffens Pfingsten 2014 zu 99,- € im Vorverkauf (inkl. VVK-Gebühr). Die Veranstaltungskarte beinhaltet die Fahrtberechtigung für Nahverkehrsmittel (Straßenbahn, Busse, S-Bahn des MDV Zone 110) vom 6.Juni, 08:00 Uhr - 10.Juni, 12:00 Uhr (ohne Sonderlinien). - Zelten: mit Obsorgekarte zu 25,- € (inkl. VVK-Gebühr) mit folgendem Leistungspaket: Zeltplatznutzung auf dem Treffenzeltplatz „Pfingstbote“ – das ausführliche Treffen-Programmbuch Ohne Obsorge-Karte sind das Betreten und die Nutzung des Treffenzeltplatzes nicht möglich. Die Obsorge-Karte gilt nur in Verbindung mit einer Treffen-Veranstaltungskarte. - Parken: Für das Parken auf dem Treffengelände ist eine Parkvignette zu 15,- € (inkl. VVK-Gebühr) für den gesamten Treffen- Zeitraum erforderlich. Ohne Parkvignette ist das Parken auf dem Treffengelände (agra-Treffenpark) nicht möglich. Karten sind bestellbar über www.wave-gotik-treffen.de - Erwartete Besucherzahl: ca. 20000 - Kontakt: Fernruf: 0341-2120862 / E-Post: [email protected] - Photos: www.wave-gotik-treffen.de/photogallery.php Das Wave-Gotik-Treffen - schwarz-romantische Festspiele jedes Jahr zu Pfingsten in Leipzig 2014 findet das WGT zum 23.Mal statt. Vom 6. bis 9. Juni feiern wieder mehr als 20000 Gothics aus aller Welt DIE internationale Familienzusammenkunft der Gothic-Szene. Über die ganze Stadt verteilt werden etwa 200 Bands und Künstler auftreten und dabei erneut alle Spielarten dunkler Musik aufführen: Von Future-Pop bis Goth-Metal, von EBM bis Apocalyptic Folk, von mittelalterlichen Klängen bis zu elegischem Post Punk. -

Taming the Bourgeoisie: Grandville's Scènes De La Vie Privée Et Publique

EnterText 7.3 KERI BERG Taming the Bourgeoisie: Grandville’s Scènes de la vie privée et publique des animaux (1840-1842) Writing in 1842, an unnamed critic for L’Artiste described the caricaturist J. J. Grandville’s (1803-1847) Scènes de la vie privée et publique des animaux as a “mirror, accurate but not very flattering, in which each of us can look at ourselves and recognize ourselves.”1 The critic’s description of the illustrated book Scènes de la vie privée et publique des animaux (henceforth referred to as Les Animaux) sums up both the work and its particular mode of representation: caricature, which is the comic distortion and/or exaggeration of an original object. From political celebrations to marriage proposals, Les Animaux’s visual and verbal “scènes” from nineteenth- century life presented period readers with a deformed image of themselves, their personality traits, habits and hobbies distorted by the artist’s pencil. Grandville’s brand of caricature, however, stands out from that of his contemporaries, such as Honoré Daumier, Henri Monnier and Gavarni, in that the basis for Les Animaux’s distortion, as the title of the work suggests, is the animal. In Les Animaux, the bourgeois banker is a fattened turkey, the politician a rotund hippopotamus and the landlord a beady-eyed vulture. While the use of animal imagery and metaphors was not new in the 1840s, Grandville’s approach was, as the caricaturist created Keri Berg: Taming the Bourgeoisie 43 EnterText 7.3 hybrid creatures—animal heads atop human bodies—that visually and literally metamorphosed the person figured. -

MTO 20.2: Heetderks, Review of S. Alexander

Volume 20, Number 2, March 2014 Copyright © 2014 Society for Music Theory Review of S. Alexander Reed, Assimilate: A Critical History of Industrial Music (Oxford, 2013) David Heetderks NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.14.20.2/mto.14.20.2.heetderks.php KEYWORDS: industrial, post punk, electronic music, EBM, electronic body music, futurepop, cut-up, Throbbing Gristle, Cabaret Voltaire, Nitzer Ebb, Front 242, Skinny Puppy, Laibach, Burroughs Received March 2014 [1] The genre of industrial music is long-lived and, as is evident from comparing Audio Clip 1 and Audio Clip 2, encompasses a broad range of styles. Audio Clip 1, from “Hamburger Lady” (1978) by Throbbing Gristle, is a collage of noisy sounds and a spoken text that has been electronically modified to near indistinguishability. The only suggestion of a beat is provided by a distant thump, perhaps suggesting a heartbeat. The text assaults common notions of good taste: it describes the medical care of a severely burned woman, forcing listeners to confront a figure that civilized society would keep hidden. Audio Clip 2, from “Headhunter” (1988) by Front 242, features a driving dance beat that, in contradistinction to “Hamburger Lady,” is crisp and motoric. The lead singer shouts out the story of a bounty hunter, performing an aggressive form of masculinity. The sounds of industrial music have appeared even in recent years: the harsh and abrasive synthesizer beats in Kanye West’s 2013 album Yeezus have galvanized critics, leading some to describe a masochistic form of listening that is reminiscent of responses to industrial music. -

Goth Beauty, Style and Sexuality: Neo-Traditional Femininity in Twenty-First Century Subcultural Magazines

Citation: Nally, Claire (2018) Goth Beauty, Style and Sexuality: Neo-Traditional Femininity in Twenty-First Century Subcultural Magazines. Gothic Studies, 20 (1-2). pp. 1-28. ISSN 1362- 7937 Published by: Manchester University Press URL: https://doi.org/10.7227/GS.0024 <https://doi.org/10.7227/GS.0024> This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/28540/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html This document may differ from the final, published version of the research and has been made available online in accordance with publisher policies. To read and/or cite from the published version of the research, please visit the publisher’s website (a subscription may be required.) Gothic Studies For Review -

1 DOUBLE DÉTENTE the Role of Gaullist France and Maoist China In

DOUBLE DÉTENTE The Role of Gaullist France and Maoist China in the Formation of Cold War Détente, 1954-1973 by Alice Siqi Han A thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors Harvard University Cambridge Massachusetts 10 March 2016 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: Détente in Three Parts: The France-China-U.S. Triangle ........................................ 3 1. From Paris to Pékin .................................................................................................................. 17 2. “Opening” the China Box ......................................................................................................... 47 3. The Nixon Administration’s Search for Détente ...................................................................... 82 Conclusion: The Case for Diplomacy ......................................................................................... 113 Works Cited ................................................................................................................................ 122 2 Introduction Détente in Three Parts: The France-China-U.S. Triangle Did the historic “opening to China” during the Cold War start with the French? Conventional Cold War history portrays President Richard Nixon and his chief national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, as the principal architects of the U.S. “opening to China.”1 Part of the Nixon administration’s détente strategy, the China initiative began in 1971 with Kissinger’s -

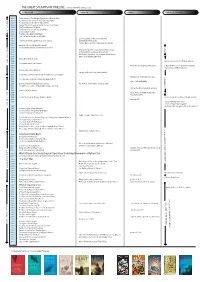

Download the Timeline and Follow Along

THE GREAT STEAMPUNK TIMELINE (to be printed A3 portrait size) LITERATURE FILM & TV GAMES PARALLEL TRACKS 1818 - Frankenstein: or The Modern Prometheus (Mary Shelley) 1864 - A Journey to the Centre of the Earth (Jules Verne) K N 1865 - From the Earth to the Moon (Jules Verne) U P 1869 - Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Jules Verne) - O 1895 - The Time Machine (HG Wells) T O 1896 - The Island of Doctor Moreau (HG Wells) R P 1897 - Dracula (Bram Stoker) 1898 - The War of the Worlds (HG Wells) 1901 - The First Men in the Moon (HG Wells) 1954 - 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Disney) 1965 - The Wolves of Willoughby Chase (Joan Aiken) The Wild Wild West (CBS) 1969 - Captain Nemo and the Underwater City (MGM) 1971 - Warlord of the Air (Michael Moorcock) 1973 - A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! (Harry Harrison) K E N G 1975 - The Land That Time Forgot (Amicus Productions) U A 1976 - At the Earth's Core (Amicus Productions) P S S 1977 - The People That Time Forgot (Amicus Productions) A R 1978 - Warlords of Atlantis (EMI Films) B Y 1979 - Morlock Night (K. W. Jeter) L R 1982 - Burning Chrome, Omni (William Gibson) A E 1983 - The Anubis Gates (Tim Powers) 1983 - Warhammer Fantasy tabletop game > Bruce Bethke coins 'Cyberpunk' (Amazing) 1984 - Neuromancer (William Gibson) 1986 - Homunculus (James Blaylock) 1986 - Laputa Castle in the Sky (Studio Ghibli) 1987 - > K. W. Jeter coins term 'steampunk' in a letter to Locus magazine -

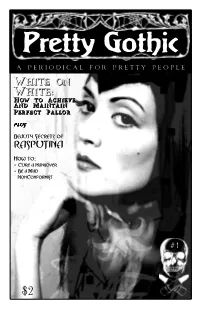

Pretty Gothic

Pretty Gothic A P e r i o d i c a l f o r P r e t t y P e o p l e White on White: HoHoHow to Achieveveve And Maintain PePePerfect Pallor plusplusplus Beauty Secrets of RASPUTINA How to: :: • Cure a Hangover • Be a Mad NonConformist #1 $2 Contributor’s PAGE Amanda Manol, Editor Sign: Aries Indispensible Beauty product: Sleep, Benefit Benetint, False Eyelashes Favorite Food: Fine Cheese, Potato Products Favorite Scent: Funeral Home Favorite Hobby: Guerilla Makeovers Kelly Ashkettle, Layout Sign: Libra Indispensible Beauty product: Ivory Powder, Black Hair Dye Favorite Food: Unagi (Eel sushi) Favorite Scent: Raspberry Lotion Favorite Hobby: DJing Margo, Photographer Sign: Aquarius Indispensible Beauty Product: Laura Mercier Concealer Favorite Food: Sashimi Favorite Scent: Lolita Lempika Favorite Hobby: Photography SALEM, Horoscopes Sign: Capricorn Indispensible Beauty Product: blood Favorite Food: Blood Favorite Scent: Blood Favorite Hobby: Blood Erik Gorr, comic Sign: Aquarius Indispensible Beauty Product: Hair Pomade, Bay Rum Cologne Favorite food: Some kind of Vegetable Soup Favorite Scent: Plastic Favorite Hobby: Making Monsters, Guitar Not Pictured: Sara Cagno, copy editing. Elise Soroka, grapHic Design cover: Model: Serafemme. Makeup: Amanda. Photography, Margo. Graphic Design: Elise. Amanda’s Thanks: Super special thanks to all my contributors for their generosity and patience, and to Ben, Klaw, both Jamies, Melora, Todd, Jimmy and Brian, Byron, my mom and dad, Jennifur Brandt, and Gothic Beauty mag. for compelling me to make this -

Neo-Gothic 2014 30/10/2015 19:07 Page1

Primer N°5 couv Neo-Gothic_2014 30/10/2015 19:07 Page1 Each volume in the series of “primers” introduces primer SERMONS | 1 one genre of medieval manuscripts to a wider Laura Light primer | 5 audience, by providing a brief, general ALCHEMY primer | 2 introduction, followed by descriptions of the Lawrence M. Principe and Laura Light manuscripts and accompanied by other useful information, such as glossaries and suggestions LAW primer | 3 for further reading. Susan L’Engle and Ariane Bergeron-Foote Medieval-like books and manuscripts from the BESTSELLERS primer | 4 late eighteenth to the early twentieth centuries Pascale Bourgain tend to get lost in the shuffle. They are not and Laura Light taken seriously by medievalists, because they NEO-GOTHIC primer | 5 LES ENLUMINURES LTD. postdate the Middle Ages; and they are not Sandra Hindman 23 East 73rd Street assimilated in a history of “modern” book with Laura Light 7th Floor, Penthouse New York, NY 10021 production, because they are anachronistic. MANUSCRIPT primer | 6 PRODUCTION Tel: (212) 717 7273 There are a great many of them. Examining a Fax: (212) 717 7278 group of just such medieval-like books, this Richard H. Rouse [email protected] and Laura Light Primer provides a short introduction to a complex subject: how artists, scribes, and DIPLOMATICS LES ENLUMINURES LTD. NEO-GOTHIC primer | 7 publishers in France, England, Germany, and the Christopher de Hamel 2970 North Lake Shore Drive Book Production and Medievalism and Ariane Bergeron-Foote Chicago, IL 60657 United States used the remote medieval past to _____________________________ Tel: (773) 929 5986 articulate aesthetic principles in the book arts at Fax: (773) 528 3976 the dawn of the modern era.