Haidar A'li, A.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social History of the Deccan, 1300–1761

ASocial History of the Deccan, 1300–1761 In this fascinating study, Richard Eaton recounts the history of southern India’s Deccan plateau from the early fourteenth century to the rise of European colonia- lism in the eighteenth. He does so, vividly, by narrating the lives of eight Indians who lived at different times during this period, and whose careers illustrate par- ticular social processes of the region’s history. In the first chapter, for example, the author recounts the tragic life of maharaja Pratapa Rudra in order to describe the demise of regional kingdoms and the rise of interregional sultanates. In the second, the life of a Sufi shaikh is used to explore the intersection of Muslim piety, holy-man charisma, and state authority. The book’s other characters include a long-distance merchant, a general, a slave, a poet, a bandit, and a female commander-regent. Woven together into a rich narrative tapestry, the stories of these eight figures shed light not only on important social processes of the Deccan plateau across four centuries, but also on the complex relations between peoples and states of north India and those to the south of the Narmada River. This study of one of the least understood parts of South Asia is a long-awaited and much-needed book by one of the most highly regarded scholars in the field. richard m. eaton is one of the premier scholars of precolonial India. His many publications include The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760 (1993), India’s Islamic Traditions, 711–1750 (2003) and Temple Desecration and Muslim States in Medieval India (2004). -

CHAPTER 2 the District of Dharwad Has Played a Pre-Eminent Role In

38 Dharwad District CHAPTER 2 HISTORY he district of Dharwad has played a pre-eminent role in the history of Karnataka. It was the T core region of the major dynasties that ruled in Karnataka such as the Badami Chalukyas, Rashtrakutas, Kalyana Chalukyas and the Adilshahis of Bijapur. To establish their hegemony in the fertile region of Belvola-300, there have been pitched battles between the Seunas and the Hoysalas. Whenever Marathas invaded the South, they made use of the district as the highway. As the hinterland growing cotton, Hubli (Rayara Hubli or Old Hubli) was a major industrial centre. When the British in their early years of trade had founded a factory at Kadwad on the banks of the Kali, the supply of textile to the factory was through old Hubli. There was a land route from Hubli to Kadra, the higher point of the Kali (till which the river was navigable) and it was through this route that merchandise from Dharwad, Bijapur and Raichur was transported. Products of thousands of textile looms from Dharwad, Bijapur and Raichur could reach the port through Hubli. In the south, Haveri and Byadgi had communication with the Kumta port. Chilly cultivation introduced into India by the Portuguese was raised here and after the British took over, transportation of cotton and chillies was made through Kumta from Byadgi and Haveri. Haveri was the main centre of cardamom processing and for final transport to Kumta. Byadgi chilly earned the name Kumta chilly due to its export from Kumta port. In England Kumta cotton was a recognised variety though it came from the Dharwad region. -

Annual Report of the Archaeological Survey of India 1934-35

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE OF INDIA - 1934 35 . EDITED BY J. F. BLAKISTON, Di;aii>r General of Atchxobgt/ tn Iniia, DELHI: MANAGER OF PUBLICATIONS 193T Prici! Rs. Jl-A <n ISt. Gd List of Agents in India from whom Government of India Publications are available. (a) Provinoial Government Book Depots. Madras : —Superintendent, Government Press, Mount Hoad, Madras. Bosibay : —Superintendent, Govommont Printing and Stationorj^ Queen’s Road, Bombay. Sind ; —Manager, Sind Government Book Depot and Record Office, Karachi (Sader). United Provinces : —Superintendent, Government Press, Allahabad. Punjab : —Superintendent, Government Printing, Punjab, Lahore. Central Provinces : —Superintendont, Govommont Printing, Central Provinces, Nagpur. Assam ; —Superintendent, Assam Secretariat Press, Shillong. Bihar : —Superintendent, Government Printing, P. O. Gulzarbagh, Patna. North-West Frontier Province:—Manager, Government Printing and Stationery, Peshawar. Orissa ; —Press Officer, Secretariat, Cuttack. (4) Private Book-seli.ers.' Advani Brothers, P. 0. Box 100, Cawnpore. Malhotra & Co., Post Box No. 94, Lahore, Messrs, XJ, P, Aero Stores, Karachi.* Malik A Sons, Sialkot City. Banthi3’a & Co., Ltd., Station Road, Ajmer. Minerva Book Shop, Anarkali Street, Lahore. Bengal Flying Club, Dum Dum Cantt,* Modem Book Depot, Bazar Road, Sialkot Cantonment Bhawnani & Sons, New Delhi. and Napier Road, JuUtmdor Cantonment. Book Company, Calcutta. Mohanlal Dessabhai Shah, Rajkot. Booklover’s Resort, Taikad, Trivandrum, South India* Nandkishoro k Bros,, Chowk, Bonaros City. “ Burma Book Club, Ltd., Rangoon. Now Book Co. Kitab Mahal ”, 192, Homby Road Bombay. ’ Butterworth &: Co. (India), Ltd., Calcutta. Nowman & Co., Ltd., Calcutta, Messrs. Careers, Mohini Road, Lahore. W. Oxford Book and Stationorj' Company, Delhi, Lahore, Chattorjeo Co., Bacharam Chatterjee Lane, 3, Simla, Meomt and Calcutta. Calcutta. -

ADIL SHAHI MOSQUES in KARNATAKA Maruti T

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITY STUDIES Vol 4, No 1, 2012 ISSN: 1309-8063 (Online) ADIL SHAHI MOSQUES IN KARNATAKA Maruti T. Kamble Department of History and Archaeology Karnatak University Dharwad - 580003 Karnataka State, India. E-mail: [email protected] -Abstract- This paper concentrates on the mosques (masjids) of the period of the Adil Shahis, one of the Muslim dynasties which had Turkish origin that ruled Karnataka along with the other parts of the Deccan. A Mosque is primarily a religious building for the performance of the daily prayers for five times, one of the five pillars of Islam. It is thus, the most important building for Muslims. Mosques in Karnataka have a long history and tradition. The Adil Shahis constructed mosques in Maharastra, Andra Pradesh and other parts of Karnataka State. Karnataka “the priceless gift of indulgent nature” is a unique blend of glorious past and rich present, situated on the lower West Coast of South India. It was ruled by the Muslim dynasties from the middle of the 14th century to 18th century. The Adil Shahis ruled Karnataka from 1489 A.D., to 1686 A.D., and wielded a great political power over many parts of Karnataka. The founder Yusuf Adil Shah was the son of Ottoman Sultan Murad II of Turkey. In their period many secular and religious monuments were constructed. The Adil Shahi mosques were not only places of worship but also places for education and social activities. The paper examines the construction of the mosques by the Adil Shahis, their patrons and also the construction pattern, architects, features and its role in the society. -

Community Oriented Storytelling Brochure

TABLE OF CONTENTS Kerala Experience -14 N/15 D 05 - 07 South India Lifescapes (Tamilnadu - Kerala - Karnataka) -18 N/19 D 08 - 10 Dravidian Routes (Exclusive Tamilnadu) -13 N/14 D 11 - 12 Brief South (Tamilnadu & Kerala) - 13 N/14 D 12 - 14 Deccan Circuit (Karnataka - Goa - Mumbai) -13 N/14 D 14 - 16 Tiger Trail (Western Ghats) - 13 N/14 D 16 - 18 Active Extension (Trekking Tour) - 04 N/05 D 18 - 19 River Nila Experience (North Kerala) -14 N/15 D 20 - 24 Short Stories - Short Experience Programs 25 School Stories - Cochin, Kerala 25 Village Life Stories - Poothotta, Kerala 25 Cochin Royal Heritage Trail - Thripunithura, Kerala 26 Cultural Immersion (Kathakali) - Cochin, Kerala 26 Mattancherry Chronicles - Cochin, Kerala 26 - 27 Pepper Trails - Cochin, Kerala 27 Village Life Stories - Manakkodam, Kerala 27 Breakfast Trail - Manakkodam, Kerala 27 Rani's Kitchen - Alleppey, Kerala 28 Tribal Stories - Marayoor, Kerala 28 Tea Trail - Munnar, Kerala 28 Meet The Nairs - Trichur, Kerala 28 - 29 Royal Family Experience - Nilambur, Kerala 29 Royal cuisine stories at Turmerica - Wayanad, Kerala 29 Tribal Cooking stories - Wayanad, Kerala 29 - 30 Madras Chronicles - Chennai, Tamilnadu 30 Meet The Franco - Tamils - Pondicherry 30 Along the River Kaveri - Tanjore Village Stories - Tanjore, Tamilnadu 30 - 31 Arts & Crafts of Tanjore - Tanjore, Tamilnadu 31 03 SOUTH INDIA A different world of Life Stories, Culture & Cuisine Travel a Dream Travel is about listening to stories - stories of the experience the beautiful part of our Country - South & making up of a country, a region, culture and its people. At Western India. Our showcased programs are only pilot ones Keralavoyages, we help you to listen to the local stories and or travelled by one of our travelers but if you have a different the life around. -

Turks in Karnataka

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITY STUDIES Vol 4, No 1, 2012 ISSN: 1309-8063 (Online) TURKS IN KARNATAKA Varija R. Bolar Dept. of History and Archaeology, Karnatak University, Dharwad-580003 Karnataka State, India Email : [email protected] -Abstract- The paper aims to highlight the contribution of the Turks from 14th to 18th Century A.D., in Karnataka State. The Turks came to India after the Arabs. They were very strong in their physique, expert in warfare and dedicated to Islam. In India, the Turkish rule was started by the Slave dynasty King named Qutbuddin-Aibak in the year 1206 A.D., which continued till 1287 A.D., under the reign of Ghiasuddin Balban. Afterwards another Turkish tribe, the Khilji dynasty ruled from 1292 A.D. to 1320 A.D. A third dynasty, the Tughluqs ruled from 1320 A.D. to 1414 A.D. They were a mixed race of Turks and Jats. All the dynasties ruled different parts of North India. Karnataka is a prominent State in South India. The first Turkish invasion into Karnataka was by the Khiljis. Malik Kafur, the General of Allauddin-Khilji carried many expeditions in South India during the period 1305 A.D. to 1311 A.D., because of these expeditions many Muslim soldiers remained in Karnataka. Among them some were Turks. Ulugh Khan (Muhammud-bin-Tughluq) the son of Ghiasuddin Tughluq also conducted military expeditions and captured Bidar and Basava Kalyana in Bidar district of North Karnataka. Hence again many Turks put their feet in Karnataka. Epigraphical and literary sources are found of the Turks living during the period of Vijayanagara Empire (1336 A.D. -

Bedkar Veedhi S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA

pincode officename districtname statename 560001 Dr. Ambedkar Veedhi S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 HighCourt S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Legislators Home S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Mahatma Gandhi Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Rajbhavan S.O (Bangalore) Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Vidhana Soudha S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 CMM Court Complex S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Vasanthanagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Bangalore G.P.O. Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560002 Bangalore Corporation Building S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560002 Bangalore City S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Malleswaram S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Palace Guttahalli S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Swimming Pool Extn S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Vyalikaval Extn S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Gavipuram Extension S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Mavalli S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Pampamahakavi Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Basavanagudi H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Thyagarajnagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560005 Fraser Town S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560006 Training Command IAF S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560006 J.C.Nagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560007 Air Force Hospital S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560007 Agram S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560008 Hulsur Bazaar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560008 H.A.L II Stage H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560009 Bangalore Dist Offices Bldg S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560009 K. G. Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Industrial Estate S.O (Bangalore) Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Rajajinagar IVth Block S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Rajajinagar H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA -

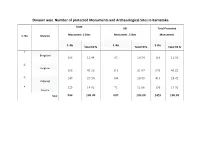

Division Wise Number of Protected Monuments and Archaeological Sites in Karnataka

Division wise Number of protected Monuments and Archaeological Sites in Karnataka State ASI Total Protected S. No Division Monument / Sites Monument / Sites Monuments S. No S. No S. No Total TO % Total TO % Total TO % 1 Bangalore 105 12.44 63 10.34 168 11.56 2 Belgaum 365 43.25 311 51.07 676 46.52 3 249 29.50 164 26.93 413 28.42 Kalgurugi 4 125 14.81 71 11.66 196 13.51 Mysore Total 844 100.00 609 100.00 1453 100.00 Division wise Number of protected Monuments and Archaeological Sites in Karnataka Bangalore Division Serial Per Total No. of Overall pre- Name of the District Number Total No. of cent Per protected protected ASI Total No. of Monument / Sites cent % Monument / protected Monument / Sites % Sites monuments 1 Bangalore City 7 2 9 2 Bangalore Rural 9 5 14 3 Chitradurga 8 6 14 4 Davangere 8 9 17 5 Kolara 15 6 21 6 Shimoga 12 26 38 7 Tumkur 29 6 35 8 Chikkaballapur 4 2 6 9 Ramanagara 13 1 14 Total 105 12.44 63 10.34 168 11.56 Division wise Number of protected Monuments and Archaeological Sites in Karnataka Belgaum Division Total No. of Overall pre- Serial Per Name of the District Total No. of Per protected protected Number cent ASI Total No. of Monument / Sites cent % Monument / protected % Monument / Sites Sites monuments 10 Bagalkot 22 110 132 11 Belgaum 58 38 96 12 Vijayapura 45 96 141 13 Dharwad 27 6 33 14 Gadag 44 14 58 15 Haveri 118 12 130 16 Uttara Kannada 51 35 86 Total 365 43.25 311 51.07 676 46.52 Division wise Number of protected Monuments and Archaeological Sites in Karnataka Kalburagi Division Serial Per Total protected -

ANSWERED ON:08.08.2016 Development of Places of Cultural Importance Yeddyurappa Shri B

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA CULTURE LOK SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO:318 ANSWERED ON:08.08.2016 Development of Places of Cultural Importance Yeddyurappa Shri B. S. Will the Minister of CULTURE be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government proposes to formulate any scheme for the development and maintenance of places of cultural importance in the country; (b) if so, the details thereof including the details of places of cultural importance identified in the State of Karnataka; (c) if not, the reasons therefor; and (d) the action taken/proposed to be taken by the Government for the development of such places? Answer MINISTER OF STATE, CULTURE AND TOURISM (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) (DR. MAHESH SHARMA) (a)to(d) A statement is laid on the table of the House. STATEMENT REFERRED TO IN REPLY TO PART (a) TO (d) OF THE LOK SABHA STARRED QUESTION No.318 FOR 08.08.2016. (a ) to (d) Madam, development and maintenance of places of cultural importance, including centrally protected monuments, under Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) is an ongoing process. Adequate funds are provided for conservation, development and maintenance of protected monuments. The details of protected monuments of ASI in Karnataka are given in annexure. The essential conservation/development works of protected monuments are attended regularly as per the availability of resources and requirements of different sites and they are in a good state of preservation. In addition on sanction of additional funds, conservation works of other monuments of cultural significance are also taken up. Annexure ANNEXURE REFERRED TO IN REPLY TO PART (a) TO (d) OF THE LOK SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO. -

List of Sites 75 for Celebration of Yoga on 21 June, 2021

List of sites for celebration of Yoga on 21 June, 2021 # - to be filled up by the Bureau heads * - to be filled up by concerned organization ** - to be filled up by SNA *** - to be fille up by SNA & ZCC bureau S. State/UT Venue Nodal Nodal person Program** Name of Artist/ Agency for stage Remark No. Organization with contact Group preparation s (Music/Dance/ # details* performance (ASI/ZCC/ Folk) (UBKYP/SNA SNA…..) (7:45 am– Awardees/ 8:15am ) ZCCs)*** 1. Arunachal Tawang T a w a n g Pardesh Monastery 2. Andhra Bapu museum, ASI Pradesh Vijayawada Virupanna (Lepakshi Temple) 3 Andaman & Anthropological AnSI Nicobar Survey office 4 Assam Ranghar Ruins ASI (Shivsagar) 5. Bihar Nalanda Nava Nalanda Mahavihara 6 Bihar Ancestral House ASI of Dr. Rajendra Prasad (Siwan) Ziradei 7 Bihar C h a m p a r a n GSDS (GSDS) 8 Bihar Kumrahar: ASI Supposed site of a P a l a c e o f Ashoka, Patna 9 Chhattisgarh Laxman temple, ASI S i r p u r , Mahasamund 10 Chhattisgarh Sub-regional AnSI o f f i c e , Anthropological Survey of India, Jagdalpur 11 Delhi Red Fort ASI 12. Daman Div Diu Fort ASI 13. D a d a r & Diu Fort ASI N a g a r Haveli 14 GOA Aguada Fort ASI 15. GOA State Central RRRLF l i b r a r y (RRRLF) 16 GOA St. Augustine ASI Church, Old Goa 17. Gujarat Rukmini ASI Temple, Dwarka 18 Gujarat Sabarmati GHSM Ashram 19. Gujarat Rani-Ki-Vav ASI 20. Gujarat The Ancient site ASI at Dholavira 21 Haryana Sheikh Chilli's ASI M a h a b a r ( T h a n e s a r ) Harsi Fort 22 Himachal Kangra Fort ASI 23 Himachal Viceregal Lodge (Rashtrapati Niwas) 24 J&K Avantiswami -

British Administration in Karnataka and Kittur Princely State

Reviews of Literature Impact Factor : 1.4716 (UIF) Volume 2 , Issue 4 / Nov 2014 ISSN:-2347-2723 _____________________________________________________________________________________________ BRITISH ADMINISTRATION IN KARNATAKA AND KITTUR PRINCELY STATE Mallikarjun I Minch Assistant professor in political science ,G P Porwal Arts Com And V V Salimath Science college, Sindagi , Dist- Bijapur (Karnataka) Abstract: The State of Kittur began its career under the patronage of the kings of Bijapur in the year 1585 and ended it by absorption in the territories of the East India Company. In the year 1624 for a short interval, it was subordinate to the Moghal Empire from 1586, when the Bijapur kingdom was conquered by Aurangzeb, until sometime after his death. During the period, unrest which followed subsequently till Karnataka was over-run by the Marathas in the regime of Bajirao-I, the state was probably independent and there after till the time of the Maratha war in 1818 it was subordinate to the Peshwas. According to the “Sanad” issued in this year by the East India Company it became a vassal state of the company until 1824. Keywords; British Administration, princely state, kittur palace, socio-economic conditions. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Kittur passed through several hands before it came to be ruled by the Desais whose more prominent ruler was queen Channamma. We get the first mention of Kittur in an inscription about the close of the 12th century. By 1534, Kittur formed an estate of Yusuf Khan who was a Turkish nobleman and a follower of Asad Khan of Belgaum. By the close of the 17th century, there emerged the most important of the Karnataka Desais, Mudi Mallappa. -

Communist Movement and Communal Question in India, 1920-1948

COMMUNIST MOVEMENT AND COMMUNAL QUESTION IN INDIA, 1920-1948 ABSTRACT y/y OF THE ,__ /< 9<,, THESIS ^Jp SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF ^^A'Sottor of pijilo^opJjp x\\ f^ IN ^' \-\ i ' HISTORY J f. \ \ ^'- '• i.. v-€f\.>-^. s^. <j »•> BY . ./ - ,j / « HABIB MANJAR Under the Supervision of DR. ISHRAT ALAM CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2008 ABSTRACT OF THESIS In colonial and post colonial India, the question of communalism is/ has been a vexing question. It was/ is the communists who addressed this question more comprehensively than any other political formation. Precisely because of this, a study of the "Communist Movement and Comruinal Question in India, 1920-48" holds great importance. The present study, consisting of 6 chapters, has made an enquiry into the question dividing its developt^ent in various phas^a It has elaborated ipon how the Communist Party of India perceived Hindu-Muslim problems vis-a vis its role in the National movement during these years. The first chapter is an introduction to the study which has analysed and scrutinized the existing major works e.g. M.R. Masani, John H. Kautsky, Gautam Chattopadhyay, Bipan Chandra, B.R. Nanda, Bhagwan Josh and Suranjan Das. These works have not focused adequately on the communal question/Hindu-Muslim relations. Some of these works ue confined to specific regions, that too addressing only marginally on ihe communal question. The 'Introduction' of the present study therefore attempts to look into the relationship of the League, Congress and Communists on the one hand and the Communist Party's attitude towards the question of 'Pakistan', on the other.