Alexander Hamilton's Use. Abuse. and Defense of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unit 3 the FEDERALIST ERA

Unit 3 THE FEDERALIST ERA CHAPTER 1 THE NEW NATION ..........................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER 2 HAMILTON AND JEFFERSON— THE MEN AND THEIR PHILOSOPHIES .....................6 CHAPTER 3 PAYING THE NATIONAL DEBT ................................................................................................12 CHAPTER 4 ..............................................................................................................................................................16 HAMILTON, JEFFERSON, AND THE FIRST NATIONAL BANK OF THE UNITED STATES.............16 CHAPTER 5 THE WHISKEY REBELLION ........................................................................................................20 CHAPTER 6 NEUTRALITY AND THE JAY TREATY .....................................................................................24 CHAPTER 7 THE SEDITION ACT AND THE VIRGINIA AND KENTUCKY RESOLUTIONS ...........28 CHAPTER 8 THE ELECTION OF 1800................................................................................................................34 CHAPTER 9 JEFFERSONIANS IN OFFICE.......................................................................................................38 by Thomas Ladenburg, copyright, 1974, 1998, 2001, 2007 100 Brantwood Road, Arlington, MA 02476 781-646-4577 [email protected] Page 1 Chapter 1 The New Nation A Search for Answers hile the Founding Fathers at the Constitutional Convention debated what powers should be -

NEWSPAPERS and PERIODICALS FINDING AID Albert H

Page 1 of 7 NEWSPAPERS AND PERIODICALS FINDING AID Albert H. Small Washingtoniana Collection Newspapers and Periodicals Listed Chronologically: 1789 The Pennsylvania Packet, and Daily Advertiser, Philadelphia, 10 Sept. 1789. Published by John Dunlap and David Claypoole. Long two-page debate about the permanent residence of the Federal government: banks of the Susquehanna River vs. the banks of the Potomac River. AS 493. The Pennsylvania Packet, and Daily Advertiser, Philadelphia, 25 Sept. 1789. Published by John Dunlap and David Claypoole. Continues to cover the debate about future permanent seat of the Federal Government, ruling out New York. Also discusses the salaries of federal judges. AS 499. The Pennsylvania Packet, and Daily Advertiser, Philadelphia, 28 Sept. 1789. Published by John Dunlap and David Claypoole. AS 947. The Pennsylvania Packet, and Daily Advertiser, Philadelphia, 8 Oct. 1789. Published by John Dunlap and David Claypoole. Archives of the United States are established. AS 501. 1790 Gazette of the United States, New York City, 17 July 1790. Report on debate in Congress over amending the act establishing the federal city. Also includes the Act of Congress passed 4 January 1790 to establish the District of Columbia. AS 864. Columbia Centinel, Boston, 3 Nov. 1790. Published by Benjamin Russell. Page 2 includes a description of President George Washington and local gentlemen surveying the land adjacent to the Potomac River to fix the proper situation for the Federal City. AS 944. 1791 Gazette of the United States, Philadelphia, 8 October, 1791. Publisher: John Fenno. Describes the location of the District of Columbia on the Potomac River. -

Inventory of Cemeteries and Burial Grounds

HAMILTON’S HERITAGE Volume 6 December 2005 Inventory of Cemeteries and Burial Grounds Hamilton Planning and Economic Development Department Development and Real Estate Division Community Planning and Design Section HAMILTON’S HERITAGE Eastlawn, Hamilton Volume 6 December 2005 Inventory of Cemeteries St. Andrew’s Presbyterian, and Burial Grounds Ancaster Grove, Dundas St. Paul’s Anglican, Glanford Smith’s Knoll, Stoney Creek West Flamborough Presbyterian, West Flamborough Contents Acknowledgements Introduction 1 History of Hamilton Cemeteries and Burial Grounds 6 Markers Monuments and Mausoleums 11 Inscriptions and Funerary Art 16 Inventory of Cemeteries and Burial Grounds Ancaster 21 Beverly 46 Binbrook 59 Dundas 69 East Flamborough 74 Glanford 83 Hamilton Downtown 88 Hamilton Mountain 99 Stoney Creek 111 West Flamborough 124 Lost/Abandoned 135 Appendix Cemetery Types 153 Cemetery Chronology 156 Glossary 158 Index 159 Contact: Joseph Muller Cultural Heritage Planner Heritage and Urban Design 905-546-2424 x1214 [email protected] Additional text, post-production, and covers: Meghan House Joseph Muller Acknowledgements This inventory was compiled and arranged under the direction of Sylvia Wray, Archivist at the Flamborough Archives, member of the Hamilton LACAC (Municipal Heritage Committee), and Chair of that Committee’s Inventory Subcommittee. During the summers of 2004 and 2005, Zachary Horn and Aaron Pingree (M.A. students at the University of Waterloo) were employed by the Flamborough Archives to undertake the field work and research necessary for this volume. Staff of the Planning and Economic Development Department thanks Sylvia, Zachary and Aaron for their hard work and dedication in the production of this volume. Hamilton’s Heritage Volume 6: Inventory of Cemeteries and Burial Grounds Page 1 INTRODUCTION This inventory of Euro-Canadian cemeteries and burial sites contains a listing of all licensed cemeteries and burial grounds that are located within the City of Hamilton. -

The Meaning of the Federalist Papers

English-Language Arts: Operational Lesson Title: The Meaning of the Federalist Papers Enduring Understanding: Equality is necessary for democracy to thrive. Essential Question: How did the constitutional system described in The Federalist Papers contribute to our national ideas about equality? Lesson Overview This two-part lesson explores the Federalist Papers. First, students engage in a discussion about how they get information about current issues. Next, they read a short history of the Federalist Papers and work in small groups to closely examine the text. Then, student pairs analyze primary source manuscripts concerning the Federalist Papers and relate these documents to what they have already learned. In an optional interactive activity, students now work in small groups to research a Federalist or Anti-Federalist and role-play this person in a classroom debate on the adoption of the Constitution. Extended writing and primary source activities follow that allow students to use their understanding of the history and significance of the Federalist Papers. Lesson Objectives Students will be able to: • Explain arguments for the necessity of a Constitution and a bill of rights. • Define democracy and republic and explain James Madison’s use of these terms. • Describe the political philosophy underpinning the Constitution as specified in the Federalist Papers using primary source examples. • Discuss and defend the ideas of the leading Federalists and Anti-Federalists on several issues in a classroom role-play debate. (Optional Activity) • Develop critical thinking, writing skills, and facility with textual evidence by examining the strengths of either Federalism or Anti-Federalism. (Optional/Extended Activities) • Use both research skills and creative writing techniques to draft a dialogue between two contemporary figures that reflects differences in Federalist and Anti-Federalist philosophies. -

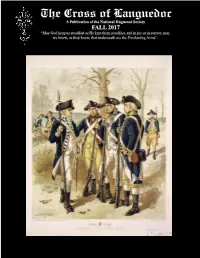

FALL 2017 “May God Keep Us Steadfast As He Kept Them Steadfast, and in Joy Or in Sorrow, May We Know, As They Knew, That Underneath Are the Everlasting Arms”

The Cross of Languedoc A Publication of the National Huguenot Society FALL 2017 “May God keep us steadfast as He kept them steadfast, and in joy or in sorrow, may we know, as they knew, that underneath are the Everlasting Arms”. COVER FEATURE – HUGUENOTS IN THE REVOLUTIONARY WAR By Editor Janice Murphy Lorenz, J.D. Cover Feature image: Infantry: Continental Army, 1779-1783, artist Henry Alexander Ogden; lithograph by G. H. Buek & Col, NY, c1897; edited by Janice Murphy Lorenz. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Expired copyright by Brig. Gen’l S.B. Holabird, Qr. Master Gen’l, U.S.A. Three of the most important values in Huguenot culture are freedom of conscience, patriotism, and courage of conviction. That is why so many men and women of Huguenot descent are prominent in the annals of early American history. One example is the many different ways in which Huguenots contributed to the American cause in the Revolutionary War. As might be imagined from regarding cover lithograph of four soldiers, which depicts the uniforms and weapons used during the period 1779 to 1783, fathers, sons, brothers and cousins fought in the war on both sides, according to their conscience. The following article from 1894 clearly emphasizes the Huguenots’ patriotic service to America’s freedom, while mentioning that some were Loyalists, too. On later pages, you will find a list prepared by Genealogist General Nancy Wright Brennan of approved Huguenot ancestors and their descendants whose patriotic service has been recognized in the patriots database maintained by the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). -

Jefferson and Franklin

Jefferson and Franklin ITH the exception of Washington and Lincoln, no two men in American history have had more books written about W them or have been more widely discussed than Jefferson and Franklin. This is particularly true of Jefferson, who seems to have succeeded in having not only bitter critics but also admiring friends. In any event, anything that can be contributed to the under- standing of their lives is important; if, however, something is dis- covered that affects them both, it has a twofold significance. It is for this reason that I wish to direct attention to a paragraph in Jefferson's "Anas." As may not be generally understood, the "Anas" were simply notes written by Jefferson contemporaneously with the events de- scribed and revised eighteen years later. For this unfortunate name, the simpler title "Jeffersoniana" might well have been substituted. Curiously enough there is nothing in Jefferson's life which has been more severely criticized than these "Anas." Morse, a great admirer of Jefferson, takes occasion to say: "Most unfortunately for his own good fame, Jefferson allowed himself to be drawn by this feud into the preparation of the famous 'Anas/ His friends have hardly dared to undertake a defense of those terrible records."1 James Truslow Adams, discussing the same subject, remarks that the "Anas" are "unreliable as historical evidence."2 Another biographer, Curtis, states that these notes "will always be a cloud upon his integrity of purpose; and, as is always the case, his spitefulness toward them injured him more than it injured Hamilton or Washington."3 I am not at all in accord with these conclusions. -

HAMILTON Project Profile 6 8 20

“HAMILTON” ONE-LINER: An unforgettable cinematic stage performance, the filmed version of the original Broadway production of “Hamilton” combines the best elements of live theater, film and streaming to bring the cultural phenomenon to homes around the world for a thrilling, once-in-a-lifetime experience. OFFICIAL BOILERPLATE: An unforgettable cinematic stage performance, the filmed version of the original Broadway production of “Hamilton” combines the best elements of live theater, film and streaming to bring the cultural phenomenon to homes around the world for a thrilling, once-in-a-lifetime experience. “Hamilton” is the story of America then, told by America now. Featuring a score that blends hip-hop, jazz, R&B and Broadway, “Hamilton” has taken the story of American founding father Alexander Hamilton and created a revolutionary moment in theatre—a musical that has had a profound impact on culture, politics, and education. Filmed at The Richard Rodgers Theatre on Broadway in June of 2016, the film transports its audience into the world of the Broadway show in a uniquely intimate way. With book, music, and lyrics by Lin-Manuel Miranda and direction by Thomas Kail, “Hamilton” is inspired by the book “Alexander Hamilton” by Ron Chernow and produced by Thomas Kail, Lin-Manuel Miranda and Jeffrey Seller, with Sander Jacobs and Jill Furman serving as executive producers. The 11-time-Tony Award®-, GRAMMY Award®-, Olivier Award- and Pulitzer Prize-winning stage musical stars: Daveed Diggs as Marquis de Lafayette/Thomas Jefferson; Renée Elise Goldsberry as Angelica Schuyler; Jonathan Groff as King George; Christopher Jackson as George Washington; Jasmine Cephas Jones as Peggy Schuyler/Maria Reynolds; Lin-Manuel Miranda as Alexander Hamilton; Leslie Odom, Jr. -

Full Screen View

A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF STATE POLITICAL PARTY NEWSPAPERS by Robert Eddy Jednak A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the College of Social Science in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida August, 1970 A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF STATE POLITICAL PARTY NEWSPAPERS by Robert Eddy Jeanak This thesis was prepared under the direction of the candidate's thesis advisor, Dr, Robert J. Huckshorn, Department of Political Science, and has been approved by the members of his super visory committee, It was submitted to the faculty of the College of Social Science and ~vas accepted in partial fulfill ment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, (Chairman, D College of Social Science) (Date) TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. STATE POLITICAL NEWSPAPERS: EVERPRESENT AND LITTLE KNOHN • • • • • • . 1 II. FIVE PROPOSITIONS TliAT TEST THE IMPORT OF THE STATE POLITICAL PARTY NEWSPAPER . 8 III. THE FINDINGS OF CONTENT ANALYSIS FOR PROPOSITIONS I-V • • • • • • . 21 IV. A TUfE ANALYSIS OF SIX SELECTED STATE POLITICAL PARTY NE\-lSPAPERS . 36 APPENDICES • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 54 BIBLIOGRAPHY • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 61 CHAPTER I STATE POLITICAL NEWSPAPERS: EVERPRESENT AND LITTLE KNOWN Thus launched as we are in an ocean of news, In hopes that your pleasure our pains will repay, All honest endeavors the author will use To furnish a feast for the grave and the gay; At least he'll essay such a track to pursue, That the \-mrld shall approve---and his ne~11s shall be true.l ~Uth the above words Philip Freneau, a poet, \vriter, and journalist of renown during the latter part of the 18th century, summarized the conduct of the political press in the October 31, 1791 issue of The National Gazette. -

Alexander Hamilton and the Development of American Law

Alexander Hamilton and the Development of American Law Katherine Elizabeth Brown Amherst, New York Master of Arts in American History, University of Virginia, 2012 Master of Arts in American History, University at Buffalo, 2010 Bachelor of Science in Applied Economics and Management, Cornell University, 2004 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia May, 2015 This dissertation is dedicated to the memory of Matthew and Theresa Mytnik, my Rana and Boppa. i ABSTRACT ―Alexander Hamilton and the Development of American Law,‖ is the first comprehensive, scholarly analysis of Alexander Hamilton‘s influence on American jurisprudence, and it provides a new approach to our understanding of the growth of federal judicial and executive power in the new republic. By exploring Hamilton's policy objectives through the lens of the law, my dissertation argues that Hamilton should be understood and evaluated as a foundational lawmaker in the early republic. He used his preferred legal toolbox, the corpus of the English common law, to make lasting legal arguments about the nature of judicial and executive power in republican governments, the boundaries of national versus state power, and the durability of individual rights. Not only did Hamilton combine American and inherited English principles to accomplish and legitimate his statecraft, but, in doing so, Hamilton had a profound influence on the substance of American law, -

Partisanship in Perspective

Partisanship in Perspective Pietro S. Nivola ommentators and politicians from both ends of the C spectrum frequently lament the state of American party politics. Our elected leaders are said to have grown exceptionally polarized — a change that, the critics argue, has led to a dysfunctional government. Last June, for example, House Republican leader John Boehner decried what he called the Obama administration’s “harsh” and “hyper-partisan” rhetoric. In Boehner’s view, the president’s hostility toward Republicans is a smokescreen to obscure Obama’s policy failures, and “diminishes the office of the president.” Meanwhile, President Obama himself has complained that Washington is a city in the grip of partisan passions, and so is failing to do the work the American people expect. “I don’t think they want more gridlock,” Obama told Republican members of Congress last year. “I don’t think they want more partisanship; I don’t think they want more obstruc- tion.” In his 2006 book, The Audacity of Hope, Obama yearned for what he called a “time before the fall, a golden age in Washington when, regardless of which party was in power, civility reigned and government worked.” The case against partisan polarization generally consists of three elements. First, there is the claim that polarization has intensified sig- nificantly over the past 30 years. Second, there is the argument that this heightened partisanship imperils sound and durable public policy, perhaps even the very health of the polity. And third, there is the impres- sion that polarized parties are somehow fundamentally alien to our form of government, and that partisans’ behavior would have surprised, even shocked, the founding fathers. -

George Chaplin: W. Sprague Holden: Newbold Noyes: Howard 1(. Smith

Ieman• orts June 1971 George Chaplin: Jefferson and The Press W. Sprague Holden: The Big Ones of Australian Journalism Newbold Noyes: Ethics-What ASNE Is All About Howard 1(. Smith: The Challenge of Reporting a Changing World NEW CLASS OF NIEMAN FELLOWS APPOINTED NiemanReports VOL. XXV, No. 2 Louis M. Lyons, Editor Emeritus June 1971 -Dwight E. Sargent, Editor- -Tenney K. Lehman, Executive Editor- Editorial Board of the Society of Nieman Fellows Jack Bass Sylvan Meyer Roy M. Fisher Ray Jenkins The Charlotte Observer Miami News University of Missouri Alabama Journal George E. Amick, Jr. Robert Lasch Robert B. Frazier John Strohmeyer Trenton Times St. Louis Post-Dispatch Eugene Register-Guard Bethlehem Globe-Times William J. Woestendiek Robert Giles John J. Zakarian E. J. Paxton, Jr. Colorado Springs Sun Knight Newspapers Boston Herald Traveler Paducah Sun-Democrat Eduardo D. Lachica Smith Hempstone, Jr. Rebecca Gross Harry T. Montgomery The Philippines Herald Washington Star Lock Haven Express Associated Press James N. Standard George Chaplin Alan Barth David Kraslow The Daily Oklahoman Honolulu Advertiser Washington Post Los Angeles Times Published quarterly by the Society of Nieman Fellows from 48 Trowbridge Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 02138. Subscription $5 a year. Third class postage paid at Boston, Mass. "Liberty will have died a little" By Archibald Cox "Liberty will have died a little," said Harvard Law allowed to speak at Harvard-Fidel Castro, the late Mal School Prof. Archibald Cox, in pleading from the stage colm X, George Wallace, William Kunstler, and others. of Sanders Theater, Mar. 26, that radical students and Last year, in this very building, speeches were made for ex-students of Harvard permit a teach-in sponsored by physical obstruction of University activities. -

October 9 Update 2FALL 2018 SYLLABUS Engl E 182A POETRY

Poetry in America: From the Mayflower Through Emerson Harvard Extension School: ENGL E-182a (CRN 15383) SYLLABUS | Fall 2018 COURSE TEAM Instructor Elisa New PhD, Powell M. Cabot Professor of American Literature, Harvard University Teaching Instructor Gillian Osborne, PhD ([email protected]) Teaching Fellows Field Brown, PhD candidate, Harvard University ([email protected]) Jacob Spencer, PhD, Harvard University ([email protected]) Course Manager Caitlin Ballotta Rajagopalan, Manager of Online Education, Poetry in America ([email protected]) ABOUT THIS COURSE This course, an installment of the multi-part Poetry in America series , covers American poetry in cultural context through the year 1850. The course begins with Puritan poets—some orthodox, some rebel spirits—who wrote and lived in early New England. Focusing on Anne Bradstreet, Edward Taylor, and Michael Wigglesworth, among others, we explore the interplay between mortal and immortal, Europe and wilderness, solitude and sociality in English North America. The second part of the course spans the poetry of America's early years, directly before and after the creation of the Republic. We examine the creation of a national identity through the lens of an emerging national literature, focusing on such poets as Phillis Wheatley, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Edgar Allen Poe, and Ralph Waldo Emerson, among others. Distinguished guest discussants in this part of the course include writer Michael Pollan, economist Larry Summers, Vice President Al Gore, Mayor Tom Menino, and others. Many of the course segments have been filmed in historic places—at Cape Cod; on the Freedom Trail in Boston; in marshes, meadows, churches, and parlors, and at sites of Revolutionary War battle.