Studies with Chess Masters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2009 U.S. Tournament.Our.Beginnings

Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis Presents the 2009 U.S. Championship Saint Louis, Missouri May 7-17, 2009 History of U.S. Championship “pride and soul of chess,” Paul It has also been a truly national Morphy, was only the fourth true championship. For many years No series of tournaments or chess tournament ever held in the the title tournament was identi- matches enjoys the same rich, world. fied with New York. But it has turbulent history as that of the also been held in towns as small United States Chess Championship. In its first century and a half plus, as South Fallsburg, New York, It is in many ways unique – and, up the United States Championship Mentor, Ohio, and Greenville, to recently, unappreciated. has provided all kinds of entertain- Pennsylvania. ment. It has introduced new In Europe and elsewhere, the idea heroes exactly one hundred years Fans have witnessed of choosing a national champion apart in Paul Morphy (1857) and championship play in Boston, and came slowly. The first Russian Bobby Fischer (1957) and honored Las Vegas, Baltimore and Los championship tournament, for remarkable veterans such as Angeles, Lexington, Kentucky, example, was held in 1889. The Sammy Reshevsky in his late 60s. and El Paso, Texas. The title has Germans did not get around to There have been stunning upsets been decided in sites as varied naming a champion until 1879. (Arnold Denker in 1944 and John as the Sazerac Coffee House in The first official Hungarian champi- Grefe in 1973) and marvelous 1845 to the Cincinnati Literary onship occurred in 1906, and the achievements (Fischer’s winning Club, the Automobile Club of first Dutch, three years later. -

Issue 16, June 2019 -...CHESSPROBLEMS.CA

...CHESSPROBLEMS.CA Contents 1 Originals 746 . ISSUE 16 (JUNE 2019) 2019 Informal Tourney....... 746 Hors Concours............ 753 2 Articles 755 Andreas Thoma: Five Pendulum Retros with Proca Anticirce.. 755 Jeff Coakley & Andrey Frolkin: Multicoded Rebuses...... 757 Arno T¨ungler:Record Breakers VIII 766 Arno T¨ungler:Pin As Pin Can... 768 Arno T¨ungler: Circe Series Tasks & ChessProblems.ca TT9 ... 770 3 ChessProblems.ca TT10 785 4 Recently Honoured Canadian Compositions 786 5 My Favourite Series-Mover 800 6 Blast from the Past III: Checkmate 1902 805 7 Last Page 808 More Chess in the Sky....... 808 Editor: Cornel Pacurar Collaborators: Elke Rehder, . Adrian Storisteanu, Arno T¨ungler Originals: [email protected] Articles: [email protected] Chess drawing by Elke Rehder, 2017 Correspondence: [email protected] [ c Elke Rehder, http://www.elke-rehder.de. Reproduced with permission.] ISSN 2292-8324 ..... ChessProblems.ca Bulletin IIssue 16I ORIGINALS 2019 Informal Tourney T418 T421 Branko Koludrovi´c T419 T420 Udo Degener ChessProblems.ca's annual Informal Tourney Arno T¨ungler Paul R˘aican Paul R˘aican Mirko Degenkolbe is open for series-movers of any type and with ¥ any fairy conditions and pieces. Hors concours compositions (any genre) are also welcome! ! Send to: [email protected]. " # # ¡ 2019 Judge: Dinu Ioan Nicula (ROU) ¥ # 2019 Tourney Participants: ¥!¢¡¥£ 1. Alberto Armeni (ITA) 2. Rom´eoBedoni (FRA) C+ (2+2)ser-s%36 C+ (2+11)ser-!F97 C+ (8+2)ser-hsF73 C+ (12+8)ser-h#47 3. Udo Degener (DEU) Circe Circe Circe 4. Mirko Degenkolbe (DEU) White Minimummer Leffie 5. Chris J. Feather (GBR) 6. -

More About Checkmate

MORE ABOUT CHECKMATE The Queen is the best piece of all for getting checkmate because it is so powerful and controls so many squares on the board. There are very many ways of getting CHECKMATE with a Queen. Let's have a look at some of them, and also some STALEMATE positions you must learn to avoid. You've already seen how a Rook can get CHECKMATE XABCDEFGHY with the help of a King. Put the Black King on the side of the 8-+k+-wQ-+( 7+-+-+-+-' board, the White King two squares away towards the 6-+K+-+-+& middle, and a Rook or a Queen on any safe square on the 5+-+-+-+-% same side of the board as the King will give CHECKMATE. 4-+-+-+-+$ In the first diagram the White Queen checks the Black King 3+-+-+-+-# while the White King, two squares away, stops the Black 2-+-+-+-+" King from escaping to b7, c7 or d7. If you move the Black 1+-+-+-+-! King to d8 it's still CHECKMATE: the Queen stops the Black xabcdefghy King moving to e7. But if you move the Black King to b8 is CHECKMATE! that CHECKMATE? No: the King can escape to a7. We call this sort of CHECKMATE the GUILLOTINE. The Queen comes down like a knife to chop off the Black King's head. But there's another sort of CHECKMATE that you can ABCDEFGH do with a King and Queen. We call this one the KISS OF 8-+k+-+-+( DEATH. Put the Black King on the side of the board, 7+-wQ-+-+-' the White Queen on the next square towards the middle 6-+K+-+-+& and the White King where it defends the Queen and you 5+-+-+-+-% 4-+-+-+-+$ get something like our next diagram. -

Caissa Nieuws

rvd v CAISSA NIEUWS -,1. 374 Met een vraagtecken priJ"ken alleen die zetten, die <!-Cl'.1- logiSchcnloop der partij werkelijk ingrijpend vemol"en. Voor zichzelf·sprekende dreigingen zijn niet vermeld. · Ah, de klassieken ... april 1999 Caissanieuws 37 4 april 1999 Colofon Inhoud Redactioneel meer is, hij zegt toe uit de doeken te doen 4. Gerard analyseert de pijn. hoe je een eindspeldatabase genereert. CaïssaNieuws is het clubblad van de Wellicht is dat iets voor Ed en Leo, maar schaakvereniging Caïssa 6. Rikpareert Predrag. Dik opgericht 1-5-1951 6. Dennis komt met alle standen. verder ook voor elke Caïssaan die zijn of it is een nummer. Met een schaak haar spel wil verbeteren. Daar zijn we wel Clublokaal: Oranjehuis 8. Derde nipt naar zege. dik Van Ostadestraat 153 vrije avond en nog wat feestdagen in benieuwd naar. 10. Zesde langs afgrond. 1073 TKAmsterdam hetD vooruitzicht is dat wel prettig. Nog aan Tot slot een citaat uit de bespreking van Telefoon - clubavond: 679 55 59 dinsda_g_ 13. Maarten heeftnotatie-biljet op genamer is het te merken dat er mensen Robert Kikkert van een merkwaardig boek Voorzitter de rug. zijn die de moeite willen nemen een bij dat weliswaar de Grünfeld-verdediging als Frans Oranje drage aan het clubblad te leveren zonder onderwerp heeft, maar ogenschijnlijk ook Oudezijds Voorburgwal 109 C 15. Tuijl vloert Vloermans. 1012 EM Amsterdam 17. Johan ziet licht aan de horizon. dat daar om gevraagd is. Zo moet het! een ongebruikelijke visieop ons multi-culti Telefoon 020 627 70 17 18. Leo biedt opwarmertje. In deze aflevering van CN zet Gerard wereldje bevat en daarbij enpassant het we Wedstrijdleider interne com12etitie nauwgezet uiteen dat het beter kanen moet reldvoedselverdelingsvraagstukaan de orde Steven Kuypers 20. -

Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25

Title: Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25 Introduction The UCS contains symbols for the game of chess in the Miscellaneous Symbols block. These are used in figurine notation, a common variation on algebraic notation in which pieces are represented in running text using the same symbols as are found in diagrams. While the symbols already encoded in Unicode are sufficient for use in the orthodox game, they are insufficient for many chess problems and variant games, which make use of extended sets. 1. Fairy chess problems The presentation of chess positions as puzzles to be solved predates the existence of the modern game, dating back to the mansūbāt composed for shatranj, the Muslim predecessor of chess. In modern chess problems, a position is provided along with a stipulation such as “white to move and mate in two”, and the solver is tasked with finding a move (called a “key”) that satisfies the stipulation regardless of a hypothetical opposing player’s moves in response. These solutions are given in the same notation as lines of play in over-the-board games: typically algebraic notation, using abbreviations for the names of pieces, or figurine algebraic notation. Problem composers have not limited themselves to the materials of the conventional game, but have experimented with different board sizes and geometries, altered rules, goals other than checkmate, and different pieces. Problems that diverge from the standard game comprise a genre called “fairy chess”. Thomas Rayner Dawson, known as the “father of fairy chess”, pop- ularized the genre in the early 20th century. -

Chess Rules Ages 10 & up • for 2 Players

Front (Head to Head) Prints Pantone 541 Blue Chess Rules Ages 10 & Up • For 2 Players Contents: Game Board, 16 ivory and 16 black Play Pieces Object: To threaten your opponent’s King so it cannot escape. Play Pieces: Set Up: Ivory Play Pieces: Black Play Pieces: Pawn Knight Bishop Rook Queen King Terms: Ranks are the rows of squares that run horizontally on the Game Board and Files are the columns that run vertically. Diagonals run diagonally. Position the Game Board so that the red square is at the bottom right corner for each player. Place the Ivory Play Pieces on the first rank from left to right in order: Rook, Knight, Bishop, Queen, King, Bishop, Knight and Rook. Place all of the Pawns on the second rank. Then place the Black Play Pieces on the board as shown in the diagram. Note: the Ivory Queen will be on a red square and the black Queen will be on a black space. Play: Ivory always plays first. Players alternate turns. Only one Play Piece may be moved on a turn, except when castling (see description on back). All Play Pieces must move in a straight path, except for the Knight. Also, the Knight is the only Play Piece that is allowed to jump over another Play Piece. Play Piece Moves: A Pawn moves forward one square at a time. There are two exceptions to this rule: 1. On a Pawn’s first move, it can move forward one or two squares. 2. When capturing a piece (see description on back), a Pawn moves one square diagonally ahead. -

YEARBOOK the Information in This Yearbook Is Substantially Correct and Current As of December 31, 2020

OUR HERITAGE 2020 US CHESS YEARBOOK The information in this yearbook is substantially correct and current as of December 31, 2020. For further information check the US Chess website www.uschess.org. To notify US Chess of corrections or updates, please e-mail [email protected]. U.S. CHAMPIONS 2002 Larry Christiansen • 2003 Alexander Shabalov • 2005 Hakaru WESTERN OPEN BECAME THE U.S. OPEN Nakamura • 2006 Alexander Onischuk • 2007 Alexander Shabalov • 1845-57 Charles Stanley • 1857-71 Paul Morphy • 1871-90 George H. 1939 Reuben Fine • 1940 Reuben Fine • 1941 Reuben Fine • 1942 2008 Yury Shulman • 2009 Hikaru Nakamura • 2010 Gata Kamsky • Mackenzie • 1890-91 Jackson Showalter • 1891-94 Samuel Lipchutz • Herman Steiner, Dan Yanofsky • 1943 I.A. Horowitz • 1944 Samuel 2011 Gata Kamsky • 2012 Hikaru Nakamura • 2013 Gata Kamsky • 2014 1894 Jackson Showalter • 1894-95 Albert Hodges • 1895-97 Jackson Reshevsky • 1945 Anthony Santasiere • 1946 Herman Steiner • 1947 Gata Kamsky • 2015 Hikaru Nakamura • 2016 Fabiano Caruana • 2017 Showalter • 1897-06 Harry Nelson Pillsbury • 1906-09 Jackson Isaac Kashdan • 1948 Weaver W. Adams • 1949 Albert Sandrin Jr. • 1950 Wesley So • 2018 Samuel Shankland • 2019 Hikaru Nakamura Showalter • 1909-36 Frank J. Marshall • 1936 Samuel Reshevsky • Arthur Bisguier • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1953 Donald 1938 Samuel Reshevsky • 1940 Samuel Reshevsky • 1942 Samuel 2020 Wesley So Byrne • 1954 Larry Evans, Arturo Pomar • 1955 Nicolas Rossolimo • Reshevsky • 1944 Arnold Denker • 1946 Samuel Reshevsky • 1948 ONLINE: COVID-19 • OCTOBER 2020 1956 Arthur Bisguier, James Sherwin • 1957 • Robert Fischer, Arthur Herman Steiner • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1954 Arthur Bisguier • 1958 E. -

Chess Pieces – Left to Right: King, Rook, Queen, Pawn, Knight and Bishop

CCHHEESSSS by Wikibooks contributors From Wikibooks, the open-content textbooks collection Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled "GNU Free Documentation License". Image licenses are listed in the section entitled "Image Credits." Principal authors: WarrenWilkinson (C) · Dysprosia (C) · Darvian (C) · Tm chk (C) · Bill Alexander (C) Cover: Chess pieces – left to right: king, rook, queen, pawn, knight and bishop. Photo taken by Alan Light. The current version of this Wikibook may be found at: http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Chess Contents Chapter 01: Playing the Game..............................................................................................................4 Chapter 02: Notating the Game..........................................................................................................14 Chapter 03: Tactics.............................................................................................................................19 Chapter 04: Strategy........................................................................................................................... 26 Chapter 05: Basic Openings............................................................................................................... 36 Chapter 06: -

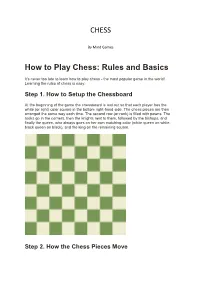

CHESS How to Play Chess: Rules and Basics

CHESS By Mind Games How to Play Chess: Rules and Basics It's never too late to learn how to play chess - the most popular game in the world! Learning the rules of chess is easy: Step 1. How to Setup the Chessboard At the beginning of the game the chessboard is laid out so that each player has the white (or light) color square in the bottom right-hand side. The chess pieces are then arranged the same way each time. The second row (or rank) is filled with pawns. The rooks go in the corners, then the knights next to them, followed by the bishops, and finally the queen, who always goes on her own matching color (white queen on white, black queen on black), and the king on the remaining square. Step 2. How the Chess Pieces Move Each of the 6 different kinds of pieces moves differently. Pieces cannot move through other pieces (though the knight can jump over other pieces), and can never move onto a square with one of their own pieces. However, they can be moved to take the place of an opponent's piece which is then captured. Pieces are generally moved into positions where they can capture other pieces (by landing on their square and then replacing them), defend their own pieces in case of capture, or control important squares in the game. How to Move the King in Chess The king is the most important piece, but is one of the weakest. The king can only move one square in any direction - up, down, to the sides, and diagonally. -

Chess Moves.Qxp

ChessChess MovesMoveskk ENGLISH CHESS FEDERATION | MEMBERS’ NEWSLETTER | July 2013 EDITION InIn thisthis issueissue ------ 100100 NOTNOT OUT!OUT! FEAFEATURETURE ARARTICLESTICLES ...... -- thethe BritishBritish ChessChess ChampionshipsChampionships 4NCL4NCL EuropeanEuropean SchoolsSchools 20132013 -- thethe finalfinal weekendweekend -- picturespictures andand resultsresults GreatGreat BritishBritish ChampionsChampions TheThe BunrBunrattyatty ChessChess ClassicClassic -- TheThe ‘Absolute‘Absolute ChampionChampion -- aa looklook backback -- NickNick PertPert waswas therethere && annotatesannotates thethe atat JonathanJonathan Penrose’Penrose’ss championshipchampionship bestbest games!games! careercareer MindedMinded toto SucceedSucceed BookshelfBookshelf lookslooks atat thethe REALREAL secretssecrets ofof successsuccess PicturedPictured -- 20122012 BCCBCC ChampionsChampions JovankJovankaa HouskHouskaa andand GawainGawain JonesJones PhotogrPhotographsaphs courtesycourtesy ofof BrendanBrendan O’GormanO’Gorman [https://picasawe[https://picasaweb.google.com/105059642136123716017]b.google.com/105059642136123716017] CONTENTS News 2 Chess Moves Bookshelf 30 100 NOT OUT! 4 Book Reviews - Gary Lane 35 Obits 9 Grand Prix Leader Boards 36 4NCL 11 Calendar 38 Great British Champions - Jonathan Penrose 13 Junior Chess 18 The Bunratty Classic - Nick Pert 22 Batsford Competition 29 News GM Norm for Yang-Fang Zhou Congratulations to 18-year-old Yang-Fan Zhou (far left), who won the 3rd Big Slick International (22-30 June) GM norm section with a score of 7/9 and recorded his first grandmaster norm. He finished 1½ points ahead of GMs Keith Arkell, Danny Gormally and Bogdan Lalic, who tied for second. In the IM norm section, 16-year-old Alan Merry (left) achieved his first international master norm by winning the section with an impressive score of 7½ out of 9. An Englishman Abroad It has been a successful couple of months for England’s (and the world’s) most travelled grandmaster, Nigel Short. In the Sigeman & Co. -

T Atlantic Chess News - July Thru September 2006 Js Official Publication of the New Jersey State Chess Federation $2.00 Q

-t Atlantic Chess News - July thru September 2006 js Official Publication Of The New Jersey State Chess Federation $2.00 q t Photo provided courtesy of Steve Ferrero Samritha Chukka Palakollu might just be one of NewJersey’s next generation of strong players to emerge. At the tender age of only 5½ , Samritha is already burning a trail of impressive results on the tournament scene. À From Your Editor’s Desk Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays to our readership! We are trying to break the cycle of getting these issues out the door in a timely manner but, as you can see, this has not yet materialized. With the end of 2006 rapidly approaching, the July – September issue arrives in your mailbox with a plethora of attacking games that you’ll love going over! Many of your favorite columnists are back with some exciting games played in New Jersey. Lev D. Zilbermintz is back to share with you his strategies of defeating masters with the Blackmar-Diemer Gambit. Life Master James R. West delves into the mind of the reclusive former world champion, GM Bobby Fischer, and his recent appearances on TV and radio. Our very own NJSCF President shines our Scholastic Spotlight on New Jersey’s latest young rising star, David Hua. I hope to see everyone at the 2007 World Amateur Team & 37th Annual Team East in February! Most games are analyzed with the assistance of the extensive and exhaustive chess playing programs, Fritz 8, Rebel II Chess Tiger 13.0, or Chess Genius© 5.028A and Grandmaster Books© add-on program running on a Pentium 4 2.8 Ghz PC with 512 megabytes of RAM running Windows XP Professional. -

Yearbook.Indb

PETER ZHDANOV Yearbook of Chess Wisdom Cover designer Piotr Pielach Typesetting Piotr Pielach ‹www.i-press.pl› First edition 2015 by Chess Evolution Yearbook of Chess Wisdom Copyright © 2015 Chess Evolution All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval sys- tem or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. isbn 978-83-937009-7-4 All sales or enquiries should be directed to Chess Evolution ul. Smutna 5a, 32-005 Niepolomice, Poland e-mail: [email protected] website: www.chess-evolution.com Printed in Poland by Drukarnia Pionier, 31–983 Krakow, ul. Igolomska 12 To my father Vladimir Z hdanov for teaching me how to play chess and to my mother Tamara Z hdanova for encouraging my passion for the game. PREFACE A critical-minded author always questions his own writing and tries to predict whether it will be illuminating and useful for the readers. What makes this book special? First of all, I have always had an inquisitive mind and an insatiable desire for accumulating, generating and sharing knowledge. Th is work is a prod- uct of having carefully read a few hundred remarkable chess books and a few thousand worthy non-chess volumes. However, it is by no means a mere compilation of ideas, facts and recommendations. Most of the eye- opening tips in this manuscript come from my refl ections on discussions with some of the world’s best chess players and coaches. Th is is why the book is titled Yearbook of Chess Wisdom: it is composed of 366 self-suffi - cient columns, each of which is dedicated to a certain topic.