Amelia [Film Review]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blacks and Asians in Mississippi Masala, Barriers to Coalition Building

Both Edges of the Margin: Blacks and Asians in Mississippi Masala, Barriers to Coalition Building Taunya Lovell Bankst Asians often take the middle position between White privilege and Black subordination and therefore participate in what Professor Banks calls "simultaneous racism," where one racially subordinatedgroup subordi- nates another. She observes that the experience of Asian Indian immi- grants in Mira Nair's film parallels a much earlier Chinese immigrant experience in Mississippi, indicatinga pattern of how the dominantpower uses law to enforce insularityamong and thereby control different groups in a pluralistic society. However, Banks argues that the mere existence of such legal constraintsdoes not excuse the behavior of White appeasement or group insularityamong both Asians and Blacks. Instead,she makes an appealfor engaging in the difficult task of coalition-buildingon political, economic, socialand personallevels among minority groups. "When races come together, as in the present age, it should not be merely the gathering of a crowd; there must be a bond of relation, or they will collide...." -Rabindranath Tagore1 "When spiders unite, they can tie up a lion." -Ethiopian proverb I. INTRODUCTION In the 1870s, White land owners recruited poor laborers from Sze Yap or the Four Counties districts in China to work on plantations in the Mis- sissippi Delta, marking the formal entry of Asians2 into Mississippi's black © 1998 Asian Law Journal, Inc. I Jacob A. France Professor of Equality Jurisprudence, University of Maryland School of Law. The author thanks Muriel Morisey, Maxwell Chibundu, and Frank Wu for their suggestions and comments on earlier drafts of this Article. 1. -

Zonta 100 Intermezzo 1 1919-1939 Dear Zontians

Zonta 100 intermezzo 1 1919-1939 Dear Zontians, My name is Amelia Earhart, woman, aviation pioneer, proud member of Zonta. I joined Zonta as a member of Boston Zonta club. The confederation of Zonta clubs was founded in 1919 in Buffalo, USA and Mary Jenkins was the first elected president. By the time I became a member, about ten years later, Zonta was an international organization thanks to the founding of a club in Toronto in 1927. Just a few weeks after I became a member, I was inducted into Zonta International. I served as an active member first in the Boston club and later in the New York club. I tributed especially to one of the ideals of Zonta International: actively promoting women to take on non-traditional fields. I wrote articles about aviation for Cosmopolitan magazine as an associate editor, served as a career counselor to women university students, and lectured at Zonta club meetings, urging members to interest themselves in aviation. Outside our ‘Zontaworld’ was and is a lot going on. After years of campaigning, the women’s suffrage movement finally achieved what they wanted for such a long time. In several countries around the world, women got the right to vote. Yet, there is still a lot of work to do before men and women have equal rights, not only in politics. In America, president Wilson suffered a blood clot which made him totally incapable of performing the duties of the presidency; the First Lady, Edith Wilson, stepped in and assumed his role. She controlled access to the president and made policy decisions on his behalf. -

Navigating Discrimination

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Educational Policy Studies Dissertations Department of Educational Policy Studies Spring 5-16-2014 Navigating Discrimination: A Historical Examination of Womens’ Experiences of Discrimination and Triumph within the United States Military and Higher Educational Institutions Dackri Davis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/eps_diss Recommended Citation Davis, Dackri, "Navigating Discrimination: A Historical Examination of Womens’ Experiences of Discrimination and Triumph within the United States Military and Higher Educational Institutions." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2014. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/eps_diss/110 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Educational Policy Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Educational Policy Studies Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ACCEPTANCE This dissertation, NAVIGATING DISCRIMINATION: A HISTORICAL EXAMINATION OF WOMENS’ EXPERIENCES OF DISCRIMINATION AND TRIUMPH WITHIN THE UNITED STATES MILITARY AND HIGHER EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS, by DACKRI DIONNE DAVIS, was prepared under the direction of the candidate’s Dissertation Advisory Committee. It is accepted by the committee members in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Education, Georgia State University. The Dissertation Advisory Committee and the student’s Department Chair, as representative of the faculty, certify that this dissertation has met all standards of excellence and scholarship as determined by the faculty. ______________________ ____________________ Deron Boyles, Ph.D. Philo Hutcheson, Ph.D. Committee Chair Committee Member ______________________ ____________________ Megan Sinnott, Ph.D. -

A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2015 Active Critical Engagement (ACE): A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices Sultana Aaliuah Shabazz University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons Recommended Citation Shabazz, Sultana Aaliuah, "Active Critical Engagement (ACE): A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2015. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/3607 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Sultana Aaliuah Shabazz entitled "Active Critical Engagement (ACE): A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Education. Barbara J. Thayer-Bacon, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Harry Dahms, Rebecca Klenk, Lois Presser Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. -

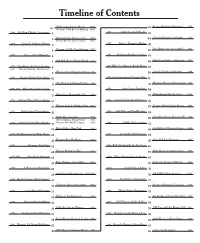

Timeline of Contents

Timeline of Contents Roots of Feminist Movement 1970 p.1 1866 Convention in Albany 1866 42 Women’s 1868 Boston Meeting 1868 1970 Artist Georgia O’Keeffe 1869 1869 Equal Rights Association 2 43 Gain for Women’s Job Rights 1971 3 Elizabeth Cady Stanton at 80 1895 44 Harriet Beecher Stowe, Author 1896 1972 Signs of Change in Media 1906 Susan B. Anthony Tribute 4 45 Equal Rights Amendment OK’d 1972 5 Women at Odds Over Suffrage 1907 46 1972 Shift From People to Politics 1908 Hopes of the Suffragette 6 47 High Court Rules on Abortion 1973 7 400,000 Cheer Suffrage March 1912 48 1973 Billie Jean King vs. Bobby Riggs 1912 Clara Barton, Red Cross Founder 8 49 1913 Harriet Tubman, Abolitionist Schools’ Sex Bias Outlawed 1974 9 Women at the Suffrage Convention 1913 50 1975 First International Women’s Day 1914 Women Making Their Mark 10 51 Margaret Mead, Anthropologist 1978 11 The Woman Sufferage Parade 1915 52 1979 Artist Louise Nevelson 1916-1917 Margaret Sanger on Trial 12 54 Philanthropist Brooke Astor 1980 13 Obstacles to Nationwide Vote 1918 55 1981 Justice Sandra Day O’Connor 1919 Suffrage Wins in House, Senate 14 56 Cosmo’s Helen Gurley Brown 1982 15 Women Gain the Right to Vote 1920 57 1984 Sally Ride and Final Frontier 1921 Birth Control Clinic Opens 16 58 Geraldine Ferraro Runs for VP 1984 17 Nellie Bly, Journalist 1922 60 Annie Oakley, Sharpshooter 1926 NOW: 20 Years Later 1928 Amelia Earhart Over Atlantic 18 Victoria Woodhull’s Legacy 1927 1986 61 Helen Keller’s New York 1932 62 Job Rights in Pregnancy Case 1987 19 1987 Facing the Subtler -

End of Year Review

End of Year Review 1 Table of Contents - Types of Communities Review - Types of Communities Sorting Activity - Then and Now Review Activity - Jobs in our Community Review Activity - Jobs in our Community Matching Activity - Goods and Services Sorting Activity - Continents of the World Map Activity - United States Map Activity - Symbols of the USA Review - Landmarks of the USA Matching Activity - President of the USA Activity - Leaders in our Community and Country Review - Leaders Sorting Activity - Holidays and Traditions Review - George Washington Carver Reading Comprehension Passage - Martin Luther King, Jr. Reading Comprehension Passage - Amelia Earhart Reading Comprehension Passage - Sally Ride Reading Comprehension Passage - Jackie Robinson Reading Comprehension Passage “Little School on the Range” © 2017 2 Types of Communities Name__________________________ Review Complete the statements using the words from the box below. RURAL URBAN SUBURBAN 1. In a rural farming community, the roads may be ____________________. 2. In urban or suburban communities, the roads are ___________________. 3. In urban areas, many people may not even own ___________ to get around. 4. In suburban areas, there are often _______________ for people to walk to places. 5. Buildings in rural areas are often spread out over large _______________. 6. People in large urban areas can travel places underground in the _________. 7. Suburban areas often have ________________ for children to play. 8. In rural communities, special equipment like ______________ may be used to help farmers. 9. In rural communities, people may have own farm animals like ___________. 10. In suburban communities, families can keep larger pets in their ________________. 11. In urban communities, families may have to own _____________ pets because there may not be room for larger pets. -

Presidential Documents 12711 Presidential Documents

Federal Register / Vol. 82, No. 42 / Monday, March 6, 2017 / Presidential Documents 12711 Presidential Documents Proclamation 9576 of March 1, 2017 Women’s History Month, 2017 By the President of the United States of America A Proclamation We are proud of our Nation’s achievements in promoting women’s full participation in all aspects of American life and are resolute in our commit- ment to supporting women’s continued advancement in America and around the world. America honors the celebrated women pioneers and leaders in our history, as well as those unsung women heroes of our daily lives. We honor those outstanding women, whose contributions to our Nation’s life, culture, history, economy, and families have shaped us and helped us fulfill America’s promise. We cherish the incredible accomplishments of early American women, who helped found our Nation and explore the great western frontier. Women have been steadfast throughout our battles to end slavery, as well as our battles abroad. And American women fought for the civil rights of women and others in the suffrage and civil rights movements. Millions of bold, fearless women have succeeded as entrepreneurs and in the workplace, all the while remaining the backbone of our families, our communities, and our country. During Women’s History Month, we pause to pay tribute to the remarkable women who prevailed over enormous barriers, paving the way for women of today to not only participate in but to lead and shape every facet of American life. Since our beginning, we have been blessed with courageous women like Henrietta Johnson, the first woman known to work as an artist in the colonies; Margaret Corbin, who bravely fought in the American Revolu- tion; and Abigail Adams, First Lady of the United States and trusted advisor to President John Adams. -

Galaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research Journal the Criterion: an International Journal in English ISSN: 0976-8165

About Us: http://www.the-criterion.com/about/ Archive: http://www.the-criterion.com/archive/ Contact Us: http://www.the-criterion.com/contact/ Editorial Board: http://www.the-criterion.com/editorial-board/ Submission: http://www.the-criterion.com/submission/ FAQ: http://www.the-criterion.com/fa/ ISSN 2278-9529 Galaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research Journal www.galaxyimrj.com www.the-criterion.com The Criterion: An International Journal In English ISSN: 0976-8165 In- Between This and That: The Anxiety and Burden of Culture in Mira Nair’s Mississippi Masala Nidhi Chadha M.A. English Literature with Communication Studies Christ University, Bengaluru. Abstract: Migrant or diasporic communities are often seen wrestling with the question of identity, a sense of home and belonging. The distress such communities have to face is a sense of this or that, a sense of anxiety between assimilation of the host country’s culture and traditions or an urge to stay in touch with their own cultural roots, traditions and practices. Mira Nair’s Mississippi Masala (1991) offers to its viewers the dilemma faced by a diasporic (Gujarati) community in Mississippi, who are lost in- between different identities. The diasporic anguish is reflected through the movie, showing a loss of culture, loss of home and above all a loss of sense of belonging somewhere. The paper will examine the ways in which culture becomes a burden along with an attempt to understand the role of space and place in the formation of one’s identity. Keywords: Diaspora, In-betweeness, culture, Post- colonial Mississippi Masala (1991) a passionate drama film directed by Mira Nair brings to its viewers an interracial romance set in the Deep South. -

Theorizing the Transcendent Persona: Amelia Earhart's Vision In

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Faculty Research and Creative Activity Communication Studies January 2010 Theorizing the Transcendent Persona: Amelia Earhart’s Vision in The unF of It Robin E. Jensen Purdue University Erin F. Doss Purdue University Claudia Irene Janssen Eastern Illinois University, [email protected] Sherrema A. Bower Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/commstudies_fac Part of the Organizational Communication Commons Recommended Citation Jensen, Robin E.; Doss, Erin F.; Janssen, Claudia Irene; and Bower, Sherrema A., "Theorizing the Transcendent Persona: Amelia Earhart’s Vision in The unF of It" (2010). Faculty Research and Creative Activity. 6. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/commstudies_fac/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication Studies at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Research and Creative Activity by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Theorizing the Transcendent Persona: Amelia Earhart’s Vision in The Fun of It Robin E. Jensen, Erin F. Doss, Claudia I. Janssen, & Sherrema A. Bower In this article, we define and theorize the ‘‘transcendent persona,’’ a discursive strategy in which a rhetor draws from a boundary-breaking accomplishment and utilizes the symbolic capital of that feat to persuasively delineate unconventional ways of communicating and behaving in society. Aviator Amelia Earhart’s autobiography The Fun of It (1932) functions as an instructive representative anecdote of this concept and demonstrates that the transcendent persona’s persuasive force hinges on one’s ability to balance distance from audiences with similarities to them. -

Freebies, Doodads, & Helpful Hints

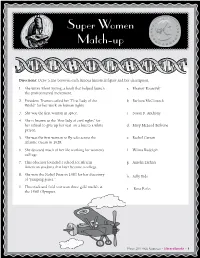

Super Women Match-up Directions: Draw a line between each famous historical figure and her description. 1. She wrote Silent Spring, a book that helped launch a. Eleanor Roosevelt the environmental movement. 2. President Truman called her “First Lady of the b. Barbara McClintock World” for her work on human rights. 3. She was the first woman in space. c. Susan B. Anthony 4. She is known as the “first lady of civil rights” for her refusal to give up her seat on a bus to a white d. Mary McLeod Bethune person. 5. She was the first woman to fly solo across the e. Rachel Carson Atlantic Ocean in 1928. 6. She devoted much of her life working for women’s f. Wilma Rudolph suffrage. 7. This educator founded a school for African g. Amelia Earhart American students that later became a college. 8. She won the Nobel Prize in 1983 for her discovery h. Sally Ride of “jumping genes.” 9. This track and field star won three gold medals at i. Rosa Parks the 1960 Olympics. March 2011 Web Resources • LibrarySparks • 1 Super Women Match-up Answer Key 1. She wrote Silent Spring, a book that helped a. Eleanor Roosevelt launch the environmental movement. 2. President Truman called her “First Lady b. Barbara McClintock of the World” for her work on human rights. 3. She was the first woman in space. c. Susan B. Anthony 4. She is known as the “first lady of civil rights” for her refusal to give up d. Mary McLeod Bethune her seat on a bus to a white person. -

![Biographies of Women Scientists for Young Readers. PUB DATE [94] NOTE 33P](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6994/biographies-of-women-scientists-for-young-readers-pub-date-94-note-33p-1256994.webp)

Biographies of Women Scientists for Young Readers. PUB DATE [94] NOTE 33P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 368 548 SE 054 054 AUTHOR Bettis, Catherine; Smith, Walter S. TITLE Biographies of Women Scientists for Young Readers. PUB DATE [94] NOTE 33p. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; *Biographies; Elementary Secondary Education; Engineering Education; *Females; Role Models; Science Careers; Science Education; *Scientists ABSTRACT The participation of women in the physical sciences and engineering woefully lags behind that of men. One significant vehicle by which students learn to identify with various adult roles is through the literature they read. This annotated bibliography lists and describes biographies on women scientists primarily focusing on publications after 1980. The sections include: (1) anthropology, (2) astronomy,(3) aviation/aerospace engineering, (4) biology, (5) chemistry/physics, (6) computer science,(7) ecology, (8) ethology, (9) geology, and (10) medicine. (PR) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** 00 BIOGRAPHIES OF WOMEN SCIENTISTS FOR YOUNG READERS 00 "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY Once of Educational Research and Improvement Catherine Bettis 14 EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION Walter S. Smith CENTER (ERIC) Olathe, Kansas, USD 233 M The; document has been reproduced aS received from the person or organization originating it 0 Minor changes have been made to improve Walter S. Smith reproduction quality University of Kansas TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES Points of view or opinions stated in this docu. INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)." ment do not necessarily rpresent official OE RI position or policy Since Title IX was legislated in 1972, enormous strides have been made in the participation of women in several science-related careers. -

Teaching About Women's Lives to Elementary School Children

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Women's Studies Quarterly Archives and Special Collections 1980 Teaching about Women's Lives to Elementary School Children Sandra Hughes How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/wsq/449 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Teaching about Women's Lives to Elementary School Children By Sandra Hughes As sixth-grade teachers with a desire to teach students about the particular surprised me, for they showed very little skepticism of historical role of women in the United States, my colleague and I a "What do we have to do this for?" nature. I found that there created a project for use in our classrooms which would was much opportunity for me to teach about the history of maximize exposure to women's history with a minimum of women in general, for each oral report would stimulate teacher effort. This approach was necessary because of the small discussion not only about the woman herself, but also about the amount of time we had available for gathering and organizing times in which she lived and the other factors that made her life material on the history of women and adapting it to the what it was. Each student seemed to take a particular pride in elementary level. the woman studied-it could be felt in the tone of their voices Since textbook material on women is practically when they began, "My woman is .