G M Book4cd.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sample Odyssey Passage

The Odyssey of Homer Translated from Greek into English prose in 1879 by S.H. Butcher and Andrew Lang. Book I In a Council of the Gods, Poseidon absent, Pallas procureth an order for the restitution of Odysseus; and appearing to his son Telemachus, in human shape, adviseth him to complain of the Wooers before the Council of the people, and then go to Pylos and Sparta to inquire about his father. Tell me, Muse, of that man, so ready at need, who wandered far and wide, after he had sacked the sacred citadel of Troy, and many were the men whose towns he saw and whose mind he learnt, yea, and many the woes he suffered in his heart upon the deep, striving to win his own life and the return of his company. Nay, but even so he saved not his company, though he desired it sore. For through the blindness of their own hearts they perished, fools, who devoured the oxen of Helios Hyperion: but the god took from them their day of returning. Of these things, goddess, daughter of Zeus, whencesoever thou hast heard thereof, declare thou even unto us. Now all the rest, as many as fled from sheer destruction, were at home, and had escaped both war and sea, but Odysseus only, craving for his wife and for his homeward path, the lady nymph Calypso held, that fair goddess, in her hollow caves, longing to have him for her lord. But when now the year had come in the courses of the seasons, wherein the gods had ordained that he should return home to Ithaca, not even there was he quit of labours, not even among his own; but all the gods had pity on him save Poseidon, who raged continually against godlike Odysseus, till he came to his own country. -

Early Theories of Foreignness (Kennedy, RECW Ch 1 Pp

Clas 122 2017 Mon Oct 2: Homer and Hesiod: Early Theories of Foreignness (Kennedy, RECW Ch 1 pp. 3-13) Overview of Homer's Odyssey -- a map of the world imagined by speakers of Greek The poem itself invites its audience to think about: What is a good society? What is a good leader? As readers here and now, we can also ask critical Questions: What are the poem's blind spots? How does the poem encourage its audience to think and behave? Do the poem's ideas about a good society and a good leader have meaning today? The images below come from a series of collages and paintings by Romare Bearden (1911-1988). The Smithsonian Institution organized a bautiful exhibit of the series recently, and there is a good free app (showing many of the works and adding audio commentary) available for I phone and android; search for "A Black Odyssey" where you get apps. As our story begins ..... During his journey back to his home in Ithaca after the war at Troy, Odysseus is on the island of Calypso. Athena asks Zeus if Odysseus can come home to Ithaca. Zeus says yes, and sends Hermes to tell Calypso that Odysseus needs to come home. Calypso lets Odysseus build a raft and he departs. This is only possible because .... RECW 1.1 Od. 1.22-26: Poseidon, the god of the sea, is visiting the Ethiopians, and thus is not watching Odysseus. Poseidon had been thwarting the homecoming because of the way that Odysseus treated the Cyclops Polyphemus, who was descended from Poseidon. -

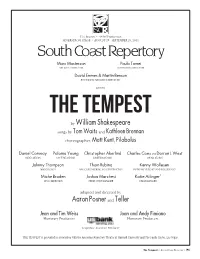

By William Shakespeare Aaron Posner and Teller

51st Season • 483rd Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / AUGUST 29 - SEPTEMBER 28, 2014 Marc Masterson Paula Tomei ARTISTIC DIRECTOR MANAGING DIRECTOR David Emmes & Martin Benson FOUNDING ARTISTIC DIRECTORS presents THE TEMPEST by William Shakespeare songs by Tom Waits and Kathleen Brennan choreographer, Matt Kent, Pilobolus Daniel Conway Paloma Young Christopher Akerlind Charles Coes AND Darron L West SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN Johnny Thompson Thom Rubino Kenny Wollesen MAGIC DESIGN MAGIC ENGINEERING AND CONSTRUCTION INSTRUMENT DESIGN AND WOLLESONICS Miche Braden Joshua Marchesi Katie Ailinger* MUSIC DIRECTION PRODUCTION MANAGER STAGE MANAGER adapted and directed by Aaron Posner and Teller Jean and Tim Weiss Joan and Andy Fimiano Honorary Producers Honorary Producers Corporate Associate Producer THE TEMPEST is presented in association with the American Repertory Theater at Harvard University and The Smith Center, Las Vegas. The Tempest • SOUTH COAST REPERTORY • P1 CAST OF CHARACTERS Prospero, a magician, a father and the true Duke of Milan ............................ Tom Nelis* Miranda, his daughter .......................................................................... Charlotte Graham* Ariel, his spirit servant .................................................................................... Nate Dendy* Caliban, his adopted slave .............................. Zachary Eisenstat*, Manelich Minniefee* Antonio, Prospero’s brother, the usurping Duke of Milan ......................... Louis Butelli* Gonzala, -

Sundance Institute Announces Casts for Summer Theatre Laboratory

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE For more information contact: June 21, 2006 Irene Cho [email protected], 801.328.3456 SUNDANCE INSTITUTE ANNOUNCES CASTS FOR SUMMER THEATRE LABORATORY AWARD-WINNING ACTORS ANTHONY RAPP, RAÚL ESPARZA AND OTHERS TO WORKSHOP SEVEN NEW PLAYS AT JULY LAB IN UTAH Salt Lake City, UT – Today, Sundance Institute announced the acting ensemble for the 2006 Sundance Institute Theatre Laboratory, to be held July 10-30, 2006 at the Sundance Resort in Utah. The company includes: Bradford Anderson, Nancy Anderson, Whitney Bashor, Judy Blazer, Reg E. Cathey, Will Chase, Johanna Day, Raúl Esparza, Jordan Gelber, Kimberly Hebert Gregory, Carla Harting, Roderick Hill, Nicholas Hormann, Christina Kirk, Ezra Knight, Judy Kuhn, Anika Larsen, Piter Marek, Kelly McCreary, Chris Messina, Jennifer Mudge, Novella Nelson, Toi Perkins, Anthony Rapp, Gareth Saxe, Tregoney Shepherd, Michael Stuhlbarg and Price Waldman. The seven plays to be developed at the 2006 Sundance Institute Theatre Laboratory include: CITIZEN JOSH, by Josh Kornbluth, directed by David Dower, an improvisational solo show which strives to rescue “democracy” from the sloganeers in a personal autobiographical format; CURRENT NOBODY, by Melissa James Gibson, directed by Daniel Aukin, a modern reinterpretation of Homer’s The Odyssey; GEOMETRY OF FIRE, by Stephen Belber, directed by Lucie Tiberghien, which weaves the story of an American reservist just back from Iraq and a Saudi-American citizen investigating his father’s death; THE EVILDOERS, by David Adjmi, directed by Rebecca Taichman, a play in which the marriage of two couples unravel in a dark yet comedic context; …AND JESUS MOONWALKS THE MISSISSIPPI, by Marcus Gardley, directed by Matt August, a poetic retelling of the Demeter myth set during the Civil War; KIND HEARTS AND CORONETS, book by Robert L. -

From the Odyssey, Part 1: the Adventures of Odysseus

from The Odyssey, Part 1: The Adventures of Odysseus Homer, translated by Robert Fitzgerald ANCHOR TEXT | EPIC POEM Archivart/Alamy Stock Photo Archivart/Alamy This version of the selection alternates original text The poet, Homer, begins his epic by asking a Muse1 to help him tell the story of with summarized passages. Odysseus. Odysseus, Homer says, is famous for fighting in the Trojan War and for Dotted lines appear next to surviving a difficult journey home from Troy.2 Odysseus saw many places and met many the summarized passages. people in his travels. He tried to return his shipmates safely to their families, but they 3 made the mistake of killing the cattle of Helios, for which they paid with their lives. NOTES Homer once again asks the Muse to help him tell the tale. The next section of the poem takes place 10 years after the Trojan War. Odysseus arrives in an island kingdom called Phaeacia, which is ruled by Alcinous. Alcinous asks Odysseus to tell him the story of his travels. I am Laertes’4 son, Odysseus. Men hold me formidable for guile5 in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky’s rim. My home is on the peaked sea-mark of Ithaca6 under Mount Neion’s wind-blown robe of leaves, in sight of other islands—Dulichium, Same, wooded Zacynthus—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy’s training; I shall not see on earth a place more dear, though I have been detained long by Calypso,7 loveliest among goddesses, who held me in her smooth caves to be her heart’s delight, as Circe of Aeaea,8 the enchantress, desired me, and detained me in her hall. -

Provided by the Internet Classics Archive. See Bottom for Copyright

Provided by The Internet Classics Archive. See bottom for copyright. Available online at http://classics.mit.edu//Homer/iliad.html The Iliad By Homer Translated by Samuel Butler ---------------------------------------------------------------------- BOOK I Sing, O goddess, the anger of Achilles son of Peleus, that brought countless ills upon the Achaeans. Many a brave soul did it send hurrying down to Hades, and many a hero did it yield a prey to dogs and vultures, for so were the counsels of Jove fulfilled from the day on which the son of Atreus, king of men, and great Achilles, first fell out with one another. And which of the gods was it that set them on to quarrel? It was the son of Jove and Leto; for he was angry with the king and sent a pestilence upon the host to plague the people, because the son of Atreus had dishonoured Chryses his priest. Now Chryses had come to the ships of the Achaeans to free his daughter, and had brought with him a great ransom: moreover he bore in his hand the sceptre of Apollo wreathed with a suppliant's wreath and he besought the Achaeans, but most of all the two sons of Atreus, who were their chiefs. "Sons of Atreus," he cried, "and all other Achaeans, may the gods who dwell in Olympus grant you to sack the city of Priam, and to reach your homes in safety; but free my daughter, and accept a ransom for her, in reverence to Apollo, son of Jove." On this the rest of the Achaeans with one voice were for respecting the priest and taking the ransom that he offered; but not so Agamemnon, who spoke fiercely to him and sent him roughly away. -

Andrew Laird

Curriculum Vitae: Andrew Laird Email [email protected] Position and current affiliations John Rowe Workman Distinguished Professor of Classics and Humanities, Professor of Hispanic Studies, Brown University Director, Brown Center for the Study of the Early Modern World Previous positions Fellow by Examination in Classical Literature, Magdalen College, Oxford Lecturer (equivalent to Assitant/Associate Professor) in Latin, Newcastle Reader and Professor of Classical Literature, Warwick Education and qualifications Magdalen College, Oxford: MA in Literae Humaniores King’s College, London: MA in Classics Magdalen College College, Oxford: D.Phil in Classical Literature Professional societies The Roman Society (Council 2007-10) Society for Latin American Studies (UK) International Association for Neo-Latin Studies Society for Classical Studies Latin American Studies Association Virgil Society (UK) Northeastern Group of Nahuatl Studies Current research collaborations • La ‘imitatio’ ecléctica de modelos clásicos y humanísticos: la poética de Zeuxis de España a Nueva España en los siglos XVI –XVIII (IIFL, UNAM, Mexico). Initiated January 2018 Previous visting positions and research awards Cátedra Extraordinaria Méndez Plancarte, Filosofía y Letras, UNAM, Mexico, 2008-9. Leverhulme Major Research Fellowship: Culture of Latin in Colonial Mexico 2009-12, Co-Investigator, European Research Council project Living Poets (2012-2015) Visting Professor, Facultad de Filología Clásica, Salamanca, March 2012 Visiting Professor and Webster Distinguished -

Homer and Collective Memory: the End of the Odyssey

Homer and Collective Memory: The End of the Odyssey This paper will approach the end of the Odyssey (starting at 24.412) by using the interpretive tools that research on collective memory has presented to us. This approach ultimately will enable us to better understand the self-awareness of the Odyssey. Building on the work of Maurice Halbwachs and Pierre Nora, research in practically every discipline of the humanities has directed its attention to the role collective memory plays in the shaping of how all kinds of sociological groups perceive themselves and their surroundings in terms of how they perceive their past, how they assess their present situation and what plans they are making for their future. This theoretical approach is also applied in Classics - not limited to, but especially in ancient history. Studies in classical literature should also avail themselves more of the tools that researchers have developed for the study of the role and the behavior of collective memories. The key for this paper will be Od. 24.484f. Zeus promises Athena that the gods will make the people of Ithaca forget that brothers and children were slain. Then, Zeus claims, people will be friends again. At the moment of this prophecy, Ithaca is at the verge of civil war. Eupeithes is trying to gather an alliance for the sake of punishing Odysseus for having lost so many comrades while he was away and for having killed all of the suitors who were members of noble families. Not all of the citizens of Ithaca want to join Eupeithes since Halitherses in particular reminds the Ithacans of the guilt of the suitors. -

AUDIOBOOKS Alice in Wonderland Around the World in 80 Days at the Back of the North Wind Birthday of the Enfanter Blue Cup Cruis

AUDIOBOOKS Alice In Wonderland Around the World in 80 days At the Back of the North Wind Birthday of the Enfanter Blue Cup Cruise of the Dazzler Devoted Friend Dragon Farm Dragons - Dreadful Dragon of Hay Hill Dragons - Kind Little Edmund Dragons - Reluctant Dragon Dragons - Snap-Dragons Dragons - The Book of Beasts Dragons - The Deliverers of Their Country Dragons - The Dragon Tamers Dragons - The Fiery Dragon Dragons - The Ice Dragon Dragons - The Isle of the Nine Whirlpools Dragons - The Last of The Dragons Dragons - Two Dragons Dragons - Uncle James Eric Prince of Lorlonia Ernest Fluffy Rabbit Faerie Queene Fifty Stories from UNCLE REMUS Fisherman and his Soul Fisherman and The Goldfish Five Children and It Gentle Alice Brown Ghost of Dorothy Dingley Goblin Market Godmother's Garden Gullivers Travels 1 - A Voyage to Lilliput Gullivers Travels 2 - A Voyage to Brobdingnag Gullivers Travels 3 A Voyage to Laputa, Balnibarbi, Luggnagg, Glubbdubdrib, and Japan Gullivers Travels 4 A Voyage to the Country of the Houynhnms Hammond's Hard Lines Happy Prince Her Majesty's Servants Horror of the Heights How I Killed a Bear Huckleberry Finn Hunting of The Snark King of The Golden River Knock Three Times Lair of The White Worm Little Boy Lost Little Round House Loaded Dog Lukundoo Lull Magic Lamplighter Malchish Kibalchish Malcolm Sage Detective Man and Snake Martin Rattler Moon Metal Moonraker Mowgli Mr Papingay's Flying Shop Mr Papingay's Ship New Sun Nightingale and Rose Nutcracker OZ 01 - Wizard of Oz OZ 02 - The Land of Oz OZ 03 - Ozma of Oz -

Anna Bonifazi, Homer's Versicolored Fabric. the Evocative Power of Ancient Greek Epic Word-Making

New England Classical Journal Volume 40 Issue 3 Pages 213-216 11-2013 Anna Bonifazi, Homer's Versicolored Fabric. The Evocative Power of Ancient Greek Epic Word-Making. Anne Mahoney Tufts University Follow this and additional works at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/necj Recommended Citation Mahoney, Anne (2013) "Anna Bonifazi, Homer's Versicolored Fabric. The Evocative Power of Ancient Greek Epic Word-Making.," New England Classical Journal: Vol. 40 : Iss. 3 , 213-216. Available at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/necj/vol40/iss3/5 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by CrossWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in New England Classical Journal by an authorized editor of CrossWorks. BOOK REVIEWS Anna Bonifazi, Homer's Versicolored Fabric. The Evocative Power of Ancient Greek Epic Word-Making. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies, 2012. Distributed by Harvard University Press. Pp. 350. Paper (ISBN 978-0-674- 06062-3) $24.95. his is a linguistic study of a1h6s and related words in epic, particularly the Odyssey but also the Iliad. Bonifazi considers first Thow a11T6s and EKE'ivos are contrasted when they refer to Odysseus, then how all the various av- words are similar. Her main tool is pragmatics, building on work by many scholars on discourse grammar in both Greek and Latin. Because she goes through a lot of basic background in this area of linguistics, with a copious bibliography, 25 pages, the book seems accessible to non-linguist classicists, though this is not really an introduction to pragmatics. In the introduction, Bonifazi says that "the general aim of this work is to contribute to an update of the grammatical accounts of some words in accord with notions and concepts from contemporary linguistics that are applicable to Homer" (10), observing that this kind of study adds precision to our understanding of pronouns, particles, and similar words, and that attention to the dialogue context can "shed more light on the standpoint of either the author or the internal characters" (11). -

The Odyssey Homer Translated Lv Robert Fitzç’Erald

I The Odyssey Homer Translated lv Robert Fitzç’erald PART 1 FAR FROM HOME “I Am Odysseus” Odysseus is in the banquet hail of Alcinous (l-sin’o-s, King of Phaeacia (fë-a’sha), who helps him on his way after all his comrades have been killed and his last vessel de stroyed. Odysseus tells the story of his adventures thus far. ‘I am Laertes’ son, Odysseus. [aertes Ia Men hold me formidable for guile in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky’s rim. My home is on the peaked sea-mark of Ithaca 4 Ithaca ith’. k) ,in island oft under Mount Neion’s wind-blown robe of leaves, the west e ast it C reece. in sight of other islands—Dulichium, Same, wooded Zacynthus—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy’s training; I (I 488 An Epic Poem I shall not see on earth a place more dear, though I have been detained long by Calypso,’ 12. Calypso k1ip’sö). loveliest among goddesses, who held me in her smooth caves, to be her heart’s delight, as Circe of Aeaea, the enchantress, 15 15. Circe (sür’së) of Aeaea e’e-). desired me, and detained me in her hail. But in my heart I never gave consent. Where shall a man find sweetness to surpass his OWfl home and his parents? In far lands he shall not, though he find a house of gold. -

Norton Antkology O F a Merican Iterature

Norton Antkology o f A merican iterature FIFTH EDITION VOLUME 2 Nina Baym, General Editor SWANLUND ENDOWED CHAIR AND CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN W • W • NORTON & COMPANY • New York • London Editor: Julia Reidhead Developmental Editor/Associate Managing Editor: Marian Johnson Production Manager: Diane O'Connor Manuscript Editors: Candace Levy, Alice Falk, Kurt Wildermuth, Kate Lovelady Instructor's Manual and Website Editor: Anna Karvellas Editorial Assistants: Tara Parmiter, Katharine Nicholson Ings Cover and Text Design: Antonina Krass Art Research: Neil Ryder Hoos Permissions: Virginia Creeden Copyright© 1998, 1994, 1989, 1985, 1979 byW. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. The text of this book is composed in Fairfield Medium with the display set in Bernhard Modern. Composition by Binghamton Valley Composition. Manufacturing by R. R. Donnelley & Sons. Cover illustration: Detail from City Activities with Dance Hall, from America Today (1930), by Thomas Hart Benton. Collection, The Equitable Life Assurance Society of the United States. Since this page cannot legibly accommodate all the copyright notices, pages 2895- 2903 constitute an extension of the copyright page. ISBN 0-393-95872-8 (pbk.) W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110 http://ww\v. wwnorton.com W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 10 Coptic Street, London WCIA IPU 12 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 Contents PREFACE TO THE FIFTH EDITION xxix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xxxiii American Literature 1865-1914 I Introduction 1 Timeline 16 SAMUEL L. CLEMENS (Mark Twain) (1835-1910) 18 The Notorious Jumping Frog of Calaveras County 21 Roughing It 25 [The Story of the Old Ram] 25 Adventures of Huckleberry Finn 28 [The Art of Authorship ] 217 How to Tell a Story 218 Fenimore Cooper's Literary Offences 221 BRET HARTE (1836-1902) 230 The Outcasts of Poker Flat 231 W.