Songs of Ascents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes on Psalms 2015 Edition Dr

Notes on Psalms 2015 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable Introduction TITLE The title of this book in the Hebrew Bible is Tehillim, which means "praise songs." The title adopted by the Septuagint translators for their Greek version was Psalmoi meaning "songs to the accompaniment of a stringed instrument." This Greek word translates the Hebrew word mizmor that occurs in the titles of 57 of the psalms. In time the Greek word psalmoi came to mean "songs of praise" without reference to stringed accompaniment. The English translators transliterated the Greek title resulting in the title "Psalms" in English Bibles. WRITERS The texts of the individual psalms do not usually indicate who wrote them. Psalm 72:20 seems to be an exception, but this verse was probably an early editorial addition, referring to the preceding collection of Davidic psalms, of which Psalm 72 was the last.1 However, some of the titles of the individual psalms do contain information about the writers. The titles occur in English versions after the heading (e.g., "Psalm 1") and before the first verse. They were usually the first verse in the Hebrew Bible. Consequently the numbering of the verses in the Hebrew and English Bibles is often different, the first verse in the Septuagint and English texts usually being the second verse in the Hebrew text, when the psalm has a title. ". there is considerable circumstantial evidence that the psalm titles were later additions."2 However, one should not understand this statement to mean that they are not inspired. As with some of the added and updated material in the historical books, the Holy Spirit evidently led editors to add material that the original writer did not include. -

Daily Devotions in the Psalms Psalm 129-133

Daily Devotions in the Psalms Psalm 129-133 Monday 12th October - Psalm 129 “Greatly have they afflicted me from my youth”— let Israel now say— 2 “Greatly have they afflicted me from my youth, yet they have not prevailed against me. 3 The plowers ploughed upon my back; they made long their furrows.” 4 The Lord is righteous; he has cut the cords of the wicked. 5 May all who hate Zion be put to shame and turned backward! 6 Let them be like the grass on the housetops, which withers before it grows up, 7 with which the reaper does not fill his hand nor the binder of sheaves his arms, 8 nor do those who pass by say, “The blessing of the Lord be upon you! We bless you in the name of the Lord!” It is interesting that Psalm 128 and 129 sit side by side. They seem to sit at odds with one another. Psalm 128 speaks of Yahweh blessing his faithful people. They enjoy prosperity and the fruit of their labour. It is a picture of peace and blessing. And then comes this Psalm, clunking like a car accidentally put into reverse. Here we see a people long afflicted (v. 1-2). As a nation, they have had their backs ploughed. And the rest of the Psalm prays for the destruction of the wicked nations and individuals who would seek to harm and destroy Israel. It’s possible that this Psalm makes you feel uncomfortable, or even wonder if this Psalm is appropriate for the lips of God’s people. -

Complete Song Book (2013 - 2016)

James Block Complete Song Book (2013 - 2016) Contents ARISE OH YAH (Psalm 68) .............................................................................................................................................. 3 AWAKE JERUSALEM (Isaiah 52) ................................................................................................................................... 4 BLESS YAHWEH OH MY SOUL (Psalm 103) ................................................................................................................ 5 CITY OF ELOHIM (Psalm 48) (Capo 1) .......................................................................................................................... 6 DANIEL 9 PRAYER .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 DELIGHT ............................................................................................................................................................................ 8 FATHER’S HEART ........................................................................................................................................................... 9 FIRSTBORN ..................................................................................................................................................................... 10 GREAT IS YOUR FAITHFULNESS (Psalm 92) ............................................................................................................. 11 HALLELUYAH -

9781845502027 Psalms Fotb

Contents Foreword ......................................................................................................7 Notes ............................................................................................................. 8 Psalm 90: Consumed by God’s Anger ......................................................9 Psalm 91: Healed by God’s Touch ...........................................................13 Psalm 92: Praise the Ltwi ........................................................................17 Psalm 93: The King Returns Victorious .................................................21 Psalm 94: The God Who Avenges ...........................................................23 Psalm 95: A Call to Praise .........................................................................27 Psalm 96: The Ltwi Reigns ......................................................................31 Psalm 97: The Ltwi Alone is King ..........................................................35 Psalm 98: Uninhibited Rejoicing .............................................................39 Psalm 99: The Ltwi Sits Enthroned ........................................................43 Psalm 100: Joy in His Presence ................................................................47 Psalm 101: David’s Godly Resolutions ...................................................49 Psalm 102: The Ltwi Will Rebuild Zion ................................................53 Psalm 103: So Great is His Love. .............................................................57 -

Psalms Psalm

Cultivate - PSALMS PSALM 126: We now come to the seventh of the "Songs of Ascent," a lovely group of Psalms that God's people would sing and pray together as they journeyed up to Jerusalem. Here in this Psalm they are praying for the day when the Lord would "restore the fortunes" of God's people (vs.1,4). 126 is a prayer for spiritual revival and reawakening. The first half is all happiness and joy, remembering how God answered this prayer once. But now that's just a memory... like a dream. They need to be renewed again. So they call out to God once more: transform, restore, deliver us again. Don't you think this is a prayer that God's people could stand to sing and pray today? Pray it this week. We'll pray it together on Sunday. God is here inviting such prayer; he's even putting the very words in our mouths. PSALM 127: This is now the eighth of the "Songs of Ascent," which God's people would sing on their procession up to the temple. We've seen that Zion / Jerusalem / The House of the Lord are all common themes in these Psalms. But the "house" that Psalm 127 refers to (in v.1) is that of a dwelling for a family. 127 speaks plainly and clearly to our anxiety-ridden thirst for success. How can anything be strong or successful or sufficient or secure... if it does not come from the Lord? Without the blessing of the Lord, our lives will come to nothing. -

Church and Organ Music. Rhythm in Hymn-Tunes Author(S): C

Church and Organ Music. Rhythm in Hymn-Tunes Author(s): C. F. Abdy Williams Source: The Musical Times, Vol. 62, No. 938 (Apr. 1, 1921), pp. 275-278 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/909413 Accessed: 03-05-2016 18:20 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Musical Times Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Musical Times This content downloaded from 128.197.26.12 on Tue, 03 May 2016 18:20:53 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms THE MUSICAL TIMES-APRIL I 192I 275 Caruso pours out his voice lavishly as ever in 'A Granada'-in fact he pours out so much of it Cbthlch anli b rgant fluic. that in a small room one instinctively looks round THE ROYAL COLLEGE OF ORGANISTS for shelter. This stirring record owes a good deal to the excellent orchestral part, in which some The following letter has been sent to the stout work is done by the castanets. members: That fine baritone, Titto Ruffo, is heard to advan- The Royal College of Organists, tage in 'Nemico della patria?' ('Andrea Ch6nier'). -

His Steadfast Love Endures Forever: General Remarks on the Psalms

Leaven Volume 4 Issue 1 The Psalms Article 3 1-1-1996 His Steadfast Love Endures Forever: General Remarks on the Psalms Timothy Willis [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/leaven Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Willis, Timothy (2012) "His Steadfast Love Endures Forever: General Remarks on the Psalms," Leaven: Vol. 4 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/leaven/vol4/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Religion at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Leaven by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Willis: His Steadfast Love Endures Forever: General Remarks on the Psalms 4 Leaven, Winter, 1996 His Steadfast Love Endures Forever General Remarks on the Book of Psalms by Tim Willis It is not my intention in this essay to layout a number of individuals who represent a variety of the way to read and study the Psalms, because I am occupations and who lived over a span of several convinced that they were purposefully written with centuries. The final stages of the era of psalms- just enough ambiguity to be read in several different composition overlap with a long process of collecting ways-from the standpoint of the individual and and arranging the psalms that encompasses much of from the standpoint of the group; in the face of the Second Temple Period (from 520 BC to 70 AD), a physical challenges and in the face of spiritual ones; process that involved yet more people. -

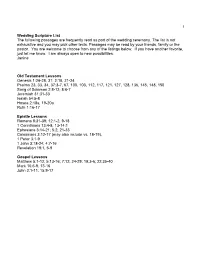

1 Wedding Scripture List the Following Passages Are Frequently Read As

1 Wedding Scripture List The following passages are frequently read as part of the wedding ceremony. The list is not exhaustive and you may pick other texts. Passages may be read by your friends, family or the pastor. You are welcome to choose from any of the listings below. If you have another favorite, just let me know. I am always open to new possibilities. Janine Old Testament Lessons Genesis 1:26-28, 31; 2:18, 21-24 Psalms 23, 33, 34, 37:3-7, 67, 100, 103, 112, 117, 121, 127, 128, 136, 145, 148, 150 Song of Solomon 2:8-13; 8:6-7 Jeremiah 31:31-33 Isaiah 54:5-8 Hosea 2:18a, 19-20a Ruth 1:16-17 Epistle Lessons Romans 8:31-39; 12:1-2, 9-18 1 Corinthians 13:4-8, 13-14:1 Ephesians 3:14-21; 5:2, 21-33 Colossians 3:12-17 (may also include vs. 18-19). 1 Peter 3:1-9 1 John 3:18-24; 4:7-16 Revelation 19:1, 5-9 Gospel Lessons Matthew 5:1-12; 5:13-16; 7:12, 24-29; 19:3-6; 22:35-40 Mark 10:6-9, 13-16 John 2:1-11; 15:9-17 2 Old Testament Lessons Genesis 1:26-28, 31 Then God said, "Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness; and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the wild animals of the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth." So God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them. -

Psalms 122-124

Songs of Ascents:122,123, 124 Psalms that lift the soul Each psalm in Psalms 120-134 has the title “a song of ascents.” Ascents may refer to pilgrimages up to Jerusalem for Passover, Pentecost, and Tabernacles. So far we have covered Psalms 120 and 121. Psalm 120 called to the Lord for help against liars and people who hate peace. In Psalm 121 the Maker of heaven and earth helps you and always watches over you. Do you go to church, or do you come to church? _______________ Psalm 122 A song of ascents. Of David. 1 I rejoiced with those who said to me, “Let us go to the house of the LORD.” 2 Our feet are standing in your gates, O Jerusalem. 3 Jerusalem is built like a city that is closely compacted together. 4 That is where the tribes go up, the tribes of the LORD, to praise the name of the LORD according to the statute given to Israel. 5 There the thrones for judgment stand, the thrones of the house of David. 6 Pray for the peace of Jerusalem: “May those who love you be secure. 7 May there be peace within your walls and security within your citadels.” 8 For the sake of my brothers and friends, I will say, “Peace be within you.” 9 For the sake of the house of the LORD our God, I will seek your prosperity. Write your own one-sentence summary of this psalm. Why do you think it brought David so much joy to go to the house of the LORD? What brings you joy in going (or coming) to the house of the LORD? Concentrate on verses 3-5. -

Exegesis of the Psalms “Selah”

Notes ! 147 BIBLE STUDY METHODS: PSALMS The Psalms are emotional. At times, God speaks too, but most of what we read are man’s words directed toward heaven. All these words are completely inspired by God. Our issue is to determine how they function as God’s Word for us. The Psalms are not: • doctrinal teaching - No! • biblical commands on our behavior - No! • illustrations of biblical principles - No! They provide examples of how people expressed themselves to God (rightly or wrongly). They give us pause to think about (1) God, and (2) our relationships to God. They ask us to consider the “ways of God.” Exegesis of the Psalms Separate them by types. Understand their different forms and their different functions. The New Testament contains 287 Old Testament quotes. 116 are from Psalms. The 150 Psalms were written over a period of about 1000 years. Moses wrote Psalm 90 in 1400B.C. Ezra wrote Psalm 1 and Psalm 119 about 444 B.C. Our task is to view the Psalms through the lens of Salvation History. “Selah” The Psalms are poetry and songs. The music is lost to us. “Selah” was intended to signal a musical pause. It’s not necessary to read it out loud. It’s a signal to pause and meditate. Though the Psalms are different from each other, they all emphasize the spirit of the Law, not the letter. Do not use them to form doctrines, independent of New Testament writings. The Psalms are emotional poetry. They often exaggerate through the emotions of their writers. The language is picturesque. -

1 Standing in Jerusalem Psalm 122 Pastor Jason Van Bemmel I Was

1 Standing in Jerusalem Psalm 122 Pastor Jason Van Bemmel I was glad when they said to me, “Let us go to the house of the LORD!” Our feet have been standing within your gates, O Jerusalem! Jerusalem – built as a city that is bound firmly together, to which the tribes go up, the tribes of the LORD, as was decreed for Israel, to give thanks to the name of the LORD. There thrones for judgment were set, the thrones of the house of David. Pray for the peace of Jerusalem! “May they be secure who love you! Peace be within your walls And security within your towers!” For my brothers and companions’ sake I will say, “Peace be within you!” For the sake of the house of the LORD our God, I will seek your good. – Psalm 122, ESV Introduction: Stage 3 of the Journey – Arrival! “Are we almost there yet?” “How much longer?” I honestly have to tell you, as Dad and driver for our long family road trips, I hate those questions. But as we do get closer to our destination, the whining and complaining are replaced by excitement and anticipation. Every journey can be broken down into three stages: the departure, the journey, and the arrival. First, you have to get up and set out, and that was covered in Psalm 120. Then, you have to make your way along the road. In this case, it’s an uphill journey, which was covered in Psalm 121. Finally, after the travel, however long, you arrive at your destination. -

Psalm 107 Sermon

They Cried, He Delivered Psalm 107 Today we begin a brief series on the Psalms.... I’ll read the first 9 verses. [read/pray] So all you need to identify with this passage is at least one problem. - Do you have a problem? “What’s your problem?” • Notice the reoccurring word “trouble” in the text. (v. 6, 13, 19, 28) • Jesus said we “will have trouble,” but to “take heart” for he’s “overcome the world” • This Psalm teaches us something else about trouble: call out to the Lord. This Psalm inspires us to cry out to the Lord no matter what kind of trouble we’re in, and no matter why we’re in trouble! • It’s a powerful Psalm about God’s rescuing love. The reason we can do this is because of “the steadfast love of the Lord,” one of the richest words in Hebrew: hesed. • We don’t have an English word that captures it well enough so it’s often translated “steadfast love” or “loyal love” or “faithful love.” • We see that word repeated over and over in this Psalm. Because of his hesed, we can call out to him in trouble... • Financial Trouble • Relationship Problems • Parenting challenges • Death and Dying • Sickness • Stress • Selling a house in the midst of a global pandemic • Trouble of Relocating • Trouble caused by your own sin or foolish decisions • violence or danger • Trouble of exams • Most of all, the trouble of being under the judgment of God; of being unconverted. This Psalm is filled with hope because we see that we can cast our cares about our God who cares for us, who is merciful to his people and faithful to his promises.