Victimization and Spillover Effects in Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogos a Nivel Entidad, Distrito Local, Municipio Y Seccion

DIRECCIÓN EJECUTIVA DEL REGISTRO FEDERAL DE ELECTORES CATALOGOS A NIVEL ENTIDAD, DISTRITO LOCAL, MUNICIPIO Y SECCION ENTIDAD NOMBRE_ENTIDAD DISTRITO_LOCAL MUNICIPIO NOMBRE_MUNICIPIO SECCION 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5207 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5208 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5209 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5210 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5211 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5212 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5213 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5214 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5215 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5216 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5217 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5218 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5219 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5220 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5221 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5222 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5223 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5224 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5225 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5226 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5227 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5228 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5229 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5230 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5231 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5232 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5233 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5234 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5235 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5236 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5237 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5238 1 DIRECCIÓN EJECUTIVA DEL REGISTRO FEDERAL DE ELECTORES CATALOGOS A NIVEL ENTIDAD, DISTRITO LOCAL, MUNICIPIO Y SECCION ENTIDAD NOMBRE_ENTIDAD DISTRITO_LOCAL MUNICIPIO NOMBRE_MUNICIPIO SECCION 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5239 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5240 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5241 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5242 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5243 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5244 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5245 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5246 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5247 15 MEXICO 1 107 TOLUCA 5248 15 -

Plan Municipal De Desarrollo Urbano De Huixquilucan, Estado De México

PLAN MUNICIPAL DE DESARROLLO URBANO DE HUIXQUILUCAN, ESTADO DE MÉXICO PLAN MUNICIPAL DE DESARROLLO URBANO DE HUIXQUILUCAN, ESTADO DE MÉXICO 2017 1 PLAN MUNICIPAL DE DESARROLLO URBANO DE HUIXQUILUCAN, ESTADO DE MÉXICO CONTENIDO I. INTRODUCCIÓN ............................................................................................................................. 6 II. PROPÓSITO Y ALCANCES DEL PLAN ....................................................................................... 7 A) Finalidad del Plan ..................................................................................................................................... 7 B) Evaluación del Plan Vigente ..................................................................................................................... 7 C) Límites Territoriales del Municipio ........................................................................................................ 15 III. MARCO JURÍDICO ...................................................................................................................... 18 A) Nivel Federal .......................................................................................................................................... 18 1. Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos .............................................................. 18 2. Ley de Planeación ......................................................................................................................... 18 3. Ley General de Asentamientos Humanos, -

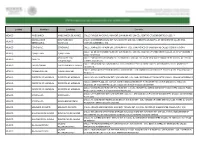

Licencias Uso De Suelo Autorizadas 2010

GOBIERNO DEL ESTADO DE MÉXICO LICENCIAS USO DE SUELO AUTORIZADAS 2010 DATOS GENERALES FECHA DE NUM MUNICIPIO UBICACIÓN PROPIETARIO USO DE SUELO EXPEDIENTE AUTORIZACION 1 APAXCO C. A PEREZ GALEANA S/N CEMENTOS APAXCO, S.A DE C.V HABITACION RLZ/049/2010 06/05/2010 2 APAXCO AVENIDA JUAREZ, No. 22 CARMELA DONIZ FLORES COMERCIO RLZ/069/2010 07/05/2010 3 APAXCO AVENIDA LA PRESA, S/N ANA MARIA MORENO MONROY HABITACION RLZ/078/2010 20/05/2010 4 APAXCO AV. JUAREZ NORTE No. 11-A A. DE CENTROS COMERCIALES S. DE R.L. DE C.V TIENDA DE AUTOSERVICIO RLZ/179/2010 06/10/2010 5 APAXCO C. JOSE MA. MORELOS, S/N ANA MARIA MORENO MONROY Y/O HABITACION RLZ/031/2010 01/03/2010 6 APAXCO AV. A. LOPEZ MATEOS S/N EMILIO AUGUSTO CORRO ORTIZ HABITACION RLZ/126/2010 21/07/2010 7 APAXCO CALLE DEL BOSQUE No. 8 SOCORRO PAULA HDEZ. ESPERILLA HABITACION RLZ/187/2010 26/10/2010 EMILIANO ZAPATA, ESQUINA DRVMZNO/RLCI/OAHU 8 COYOTEPEC GERMAN RODRIGUEZ SOLANO COMERCIO 12/02/2010 BUENAVISTA, BARRIO REYES E/028/09 DOMINGO CASTRO NUMERO 26, BARRIO HABITACIONAL Y DRVMZNO/RLCI/OAHU 9 COYOTEPEC ANTONIO PEREZ ZAMORA 17/02/2010 SAN JUAN COMERCIAL E/026/09 AVENIDA MIGUEL HIDALGO S/N, BARRIO DRVMZNO/RLCI/AHUE/ 10 COYOTEPEC MIGUEL ANGEL MELENDEZ VILLAMIL COMERCIO 01/03/2010 REYES 003/2010 AVENIDA HIDALGO SUR S/N, BARRIO HABITACIONAL Y DRVMZNO/RLCI/AHUE/ 11 COYOTEPEC ROSA MONTOYA HERNANDEZ 05/03/2010 ACOCALCO COMERCIAL 001/2010 AVENIDA HIDALGO NORTE S/N, BARRIO DRVMZNO/RLCI/AHUE/ 12 COYOTEPEC EVANGELINA MELENDEZ MONROY COMERCIO 30/04/2010 SAN JUAN 002/2010 AVENIDA CINCO DE FEBRERO S/N, -

Mexico NEI-App

APPENDIX C ADDITIONAL AREA SOURCE DATA • Area Source Category Forms SOURCE TYPE: Area SOURCE CATEGORY: Industrial Fuel Combustion – Distillate DESCRIPTION: Industrial consumption of distillate fuel. Emission sources include boilers, furnaces, heaters, IC engines, etc. POLLUTANTS: NOx, SOx, VOC, CO, PM10, and PM2.5 METHOD: Emission factors ACTIVITY DATA: • National level distillate fuel usage in the industrial sector (ERG, 2003d; PEMEX, 2003a; SENER, 2000a; SENER, 2001a; SENER, 2002a) • National and state level employee statistics for the industrial sector (CMAP 20-39) (INEGI, 1999a) EMISSION FACTORS: • NOx – 2.88 kg/1,000 liters (U.S. EPA, 1995 [Section 1.3 – Updated September 1998]) • SOx – 0.716 kg/1,000 liters (U.S. EPA, 1995 [Section 1.3 – Updated September 1998]) • VOC – 0.024 kg/1,000 liters (U.S. EPA, 1995 [Section 1.3 – Updated September 1998]) • CO – 0.6 kg/1,000 liters (U.S. EPA, 1995 [Section 1.3 – Updated September 1998]) • PM – 0.24 kg/1,000 liters (U.S. EPA, 1995 [Section 1.3 – Updated September 1998]) NOTES AND ASSUMPTIONS: • Specific fuel type is industrial diesel (PEMEX, 2003a; ERG, 2003d). • Bulk terminal-weighted average sulfur content of distillate fuel was calculated to be 0.038% (PEMEX, 2003d). • Particle size fraction for PM10 is assumed to be 50% of total PM (U.S. EPA, 1995 [Section 1.3 – Updated September 1998]). • Particle size fraction for PM2.5 is assumed to be 12% of total PM (U.S. EPA, 1995 [Section 1.3 – Updated September 1998]). • Industrial area source distillate quantities were reconciled with the industrial point source inventory by subtracting point source inventory distillate quantities from the area source distillate quantities. -

Derechos De Los Niños Y Las Niñas Derechos De La Familia Derechos De La Mujer Eventos Relevantes

PROFAMIN 31 servicios de asesoría jurídica, DERECHOS DE DERECHOS DE psicológica y de trabajo social, así LOS NIÑOS LA MUJER como despensas, ropa, juguetes y Y LAS NIÑAS útiles escolares. El siete de marzo se llevó a cabo Fechas: 03, 04, 05, 06, 07, 11, Fechas: 03, 05, 06, 07, 11, 14, una jornada comunitaria en la 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19, 25, 26 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 24, 25, 26, 28 comunidad de San Simón, y 27 de marzo, así como 01, 02, y 31 de marzo, así como 02, 03, municipio de Malinalco, 03, 07, 09, 23, 28 y 29 de abril. 08, 09, 10 y 23 de abril. otorgándose los servicios de asesoría jurídica, psicológica y de Lugares: Chalco, Ixtlahuaca, Lugares: Atlacomulco, Chalco, trabajo social, así como Jiquipilco, Malinalco, Metepec, Chimalhuacán, El Oro, despensas, juguetes, ropa, útiles Mexicaltzingo, Naucalpan de Jiquipilco, Malinalco, Metepec, escolares; de igual forma se Juárez, Ocoyoacac, Otzolotepec, Mexicaltzingo, Naucalpan de efectuaron diez visitas domiciliarias Papalotla, Morelos, Tianguistenco, Juárez, Nezahualcóyotl, Morelos, e impartieron pláticas sobre los Tejupilco, Temoaya, Tenancingo, Temoaya, Tenango del Valle, Toluca temas Derechos humanos de niños Teoloyucan, Teotihuacán, Toluca, y Villa de Allende. y niñas, Violencia intrafamiliar y Villa de Allende y Zacualpan. Asistentes: 6,901 personas. Derechos humanos de la mujer. Finalmente se realizaron diversas Asistentes: 6,901 personas. EVENTOS gestiones a fin de que la comunidad de referencia obtenga DERECHOS DE RELEVANTES atención médica por parte del LA FAMILIA Sistema para el Desarrollo Integral de la Familia del Estado de Fechas: 03, 04, 05, 06, 07, 11, 12, Los días tres y cinco de marzo se México. -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Copy The World Bank Implementation Status & Results Report Energy Efficiency in Public Facilities Project (PRESEMEH) (P149872) Energy Efficiency in Public Facilities Project (PRESEMEH) (P149872) LATIN AMERICA AND CARIBBEAN | Mexico | Energy & Extractives Global Practice | IBRD/IDA | Investment Project Financing | FY 2016 | Seq No: 9 | ARCHIVED on 26-Jun-2020 | ISR41829 | Public Disclosure Authorized Implementing Agencies: United Mexican States, Secretaría de Energía (SENER) Key Dates Key Project Dates Bank Approval Date: 08-Mar-2016 Effectiveness Date: 23-Sep-2016 Planned Mid Term Review Date: 15-Jul-2019 Actual Mid-Term Review Date: 07-Oct-2019 Original Closing Date: 31-Oct-2021 Revised Closing Date: 31-Oct-2021 pdoTable Project Development Objectives Public Disclosure Authorized Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) The objective of the project is to promote the efficient use of energy in the Borrower's municipalities by carrying outenergy efficiency investments in selected municipal sectors and contribute to strengthening the enabling environment. Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project Objective? Yes Board Approved Revised Project Development Objective (If project is formally restructured)HRPDODELs The objective is to promote the efficient use of energy in the Borrower’s municipalities and other eligible public facilities by carrying out energy efficiency investments in selected public sectors and to contribute to strengthening the enabling -

Water Governance Decentralisation and River Basin Management Reforms in Hierarchical Systems

water Article Water Governance Decentralisation and River Basin Management Reforms in Hierarchical Systems: Do They Work for Water Treatment Policy in Mexico’s Tlaxcala Atoyac Sub-Basin? Cesar Casiano Flores *, Vera Vikolainen † and Hans Bressers † Department of Governance and Technology for Sustainability (CSTM), University of Twente, Enschede 7500AE, The Netherlands; [email protected] (V.V.); [email protected] (H.B.) * Correspondence: c.a.casianofl[email protected]; Tel.: +31-68-174-6250 † These authors contributed equally to this work. Academic Editors: Sharon B. Megdal, Susanna Eden and Eylon Shamir Received: 22 February 2016; Accepted: 11 May 2016; Published: 19 May 2016 Abstract: In the last decades, policy reforms, new instruments development, and economic resources investment have taken place in water sanitation in Mexico; however, the intended goals have not been accomplished. The percentage of treated wastewater as intended in the last two federal water plans has not been achieved. The creation of River Basin Commissions and the decentralisation process have also faced challenges. In the case of Tlaxcala, the River Basin Commission exists only on paper and the municipalities do not have the resources to fulfil the water treatment responsibilities transferred to them. This lack of results poses the question whether the context was sufficiently considered when the reforms were enacted. In this research, we will study the Tlaxcala Atoyac sub-basin, where water treatment policy reforms have taken place recently with a more context sensitive approach. We will apply the Governance Assessment Tool in order to find out whether the last reforms are indeed apt for the context. -

Con Punto De Acuerdo, Por El Que Se Exhorta a La Semarnat Y a La Comisión Nacional Del Agua a Realizar Los Estudios Necesarios

CON PUNTO DE ACUERDO, POR EL QUE SE EXHORTA A LA SEMARNAT Y A LA COMISIÓN NACIONAL DEL AGUA A REALIZAR LOS ESTUDIOS NECESARIOS PARA DETERMINAR EL GRADO DE CONTAMINACIÓN EN QUE SE ENCUENTRAN LOS RÍOS ZAHUAPAN Y ATOYAC, EN EL ESTADO DE TLAXCALA, CON EL FIN DE RECUPERAR SU AFLUENTE, A CARGO DE LA DIPUTADA MARTHA PALAFOX GUTIÉRREZ, DEL GRUPO PARLAMENTARIO DEL PRI Siendo el agua un elemento indispensable para la vida y también para la vida humana, es verdaderamente una tragedia que no la cuidemos, que nos la estemos acabando. En unos casos por desperdiciarla y en otros por negligencia nuestra. Es el caso del río Zahuapan. Este afluente que en la época de la Colonia, a su agua se le atribuyeron dones curativos (Zahuapan significa el que cura los granos), hoy enfrenta niveles de contaminación alarmantes, donde este líquido ya representa un peligro para los habitantes de los municipios donde este río atraviesa (Atlangatepec, Tecupilco, Apizaco, Tlaxcala, Panotla, Zacatelco, Papalotla Nativitas, Lardizábal, entre otros). Recientemente se supo que un niño del municipio de Lardizábal que por consumir el liquido de este río falleció. La autopsia detectó la presencia de plomo y arsénico. " Dice nuestro compañero diputado Alberto Jiménez Merino en su obra Agua para el Desarrollo que "Las cuencas más contaminadas son las del Valle de México, Lerma, Altos Balsas, Pánuco y el tercio inferior del río Bravo. Los contaminantes comunes son los desechos fecales por las aguas negras, grasas y aceites, los sólidos disueltos y los detergentes... Cerca de 45% del agua para consumo humano que se distribuye en el país, esta contaminada con arsénico, hierro y manganeso, minerales que pueden provocar enfermedades como cáncer en la piel". -

S/N Num Int: S/N Col: Centro Cp 56900 Entre Calles: Y Mexi

Entidad Municipio Localidad Domicilio MEXICO AMECAMECA AMECAMECA DE JUAREZ CALLE: PARQUE NACIONAL NUM EXT: S/N NUM INT: S/N COL: CENTRO CP 56900 ENTRE CALLES: Y COACALCO DE SAN FRANCISCO CALLE: 5 DE FEBRERO NUM EXT: S/N NUM INT: S/N COL: CABECERA MUNICIPAL CP 55700 ENTRE CALLES: ESQ. MEXICO BERRIOZABAL COACALCO VICENTE GUERRERO Y S/N MEXICO COYOTEPEC COYOTEPEC CALLE: JUAN ESCUTIA NUM EXT: S/N NUM INT: COL: CHAUTONCO CP 54660 ENTRE CALLES: CONSTITUCION Y CALLE: 16 DE SEPTIEMBRE NUM EXT: 209 NUM INT: S/N COL: CENTRO CP 54800 ENTRE CALLES: 16 SE SEPTIEMBRE Y MEXICO CUAUTITLAN CUAUTITLAN AQUILES SERDAN CHALCO DE DIAZ CALLE: PORTAL DEL CIELO NUM EXT: 54 NUM INT: S/N COL: VILLAS DE CHALCO CP 56600 ENTRE CALLES: AV. DE LAS MEXICO CHALCO COVARRUBIAS TORRES Y MORELOS CALLE: MINA NUM EXT: S/N NUM INT: COL: CENTRO CP 56370 ENTRE CALLES: MEJORAMIENTO DEL AMBIENTE Y MEXICO CHICOLOAPAN CHICOLOAPAN DE JUAREZ ZARAGOZA CALLE: AVENIDA DEL PEÑON NUM EXT: S/N NUM INT: COL: BARRIO TLATELOLCO CP ENTRE CALLES: ESQUINA CALLE MEXICO CHIMALHUACAN CHIMALHUACAN HUACTLI Y MEXICO ECATEPEC DE MORELOS ECATEPEC DE MORELOS CALLE: SOL DEL NORTE NUM EXT: S/N NUM INT: COL: SAN CRISTOBAL CP 55000 ENTRE CALLES: CASA DE GOBIERNO Y CALLE: CENTER PLAZA, AV. CARLOS HANK GONZALEZ NUM EXT: 50 NUM INT: SECCION B MZ 44 COL: VALLE DE MEXICO ECATEPEC DE MORELOS ECATEPEC DE MORELOS ANAHUAC CP 55210 ENTRE CALLES: VALLE DE MEXICO Y VALLE DE JANITZIO CALLE: VIA MORELOS NUM EXT: 351 NUM INT: 1-A COL: INDUSTRIAL CERRO GORDO CP 55420 ENTRE CALLES: PLAZA MEXICO ECATEPEC DE MORELOS ECATEPEC DE MORELOS PABELLON ECATEPEC Y VIA JOSE MARIA MORELOS CALLE: LA PALMA NUM EXT: S/N NUM INT: COL: U.H. -

División Municipal De Las Entidades Federativas : Diciembre De 1964

54 ESTADOS UNIDOS MEXICANOS ESTADO DE OAXACA MUNICIPIOS CABECERAS CATEGORIAS 1, -Abejones Abejones Pueblo 2, -Acatlán de Pérez Figucroa. Acatlán de Pérez Figueroa. Pueblo 3, -Asunción Cacalotepec Asunción Cacalotepec Pueblo 4, -Asunción Cuyotepeji Asunción Cuyotepeji. Pueblo 5, -Asunción Ixtaltepcc Asunción Ixtaltepcc. Pueblo C, -Asunción Nochixtlán Asunción Nochixtlán. Villa 7, -Asunción Ocotlán Asunción Ocotlán. Pueblo 8, -Asunción Tlacolulita Asunción Tlacolulita. Pueblo 9, -Ayotziníepec (1) Ayotzintepec. ... Pueblo 10, -Barrio, El El Barrio , Pueblo 11, -Calihualá Calihua.lá Pueblo 12, -Candelaria Loxicha Candelaria Loxicha Pueblo 13, -Ciénega, La La Ciénega. Pueblo 14, -Ciudad Ixtepec (antes San Jeró- nimo Ixtepec) (2) Ixtepec (antes San Jerónimo Ixtepec). Ciudad 15, -Coatecas Altas Coatecas Altas Pueblo 10. -Coicoyán de las Flores (antes Santiago Coicoyan) (3) Coicoyán de las Flores (antes Santiago Coicoyan) Pueblo 17, -Compañía, La La Compañía (4) Pueblo 18, -Concepción Buenavista Concepción Buenavista Pueblo 19, -Concepción Pápalo Concepción Pápalo j Pueblo 20, -Constancia del Rosario Constancia del Rosario 1 Pueblo 21, -Cosolapa (5) Cosolapa ¡ Pueblo 1965 22, -Cosoltepec (antes Santa Gertru- dis Cozoltepec) (6) Cosoltepec (antes Santa Gertrudis Co- zoltepec) Pueblo 1964. 23, -Cuilapan de Guerrero Cuilapan de Guerrero Villa de 24, -Cuyamecalco Villa de Zaragoza (antes Cuyamecalco de Cancino) (7) Cuyamecalco Villa de Zaragoza (antes Cuyamecalco de Cancino) Villa 25— -Chahuites (8) Chahuites Pueblo diciembre 26— -Chalcatongo de Hidalgo. -

Tlaxcala Centro De México

TLAXCALA CENTRO DE MÉXICO ENGLISH VERSION Parish of San Bernardino Contla. Tlaxcala City Hall offices; the former House of Calpulalpan Stone; and the Xicohténcatl Theatre, Tlaxcala was one of the most important in the turn-of-the-century eclectic The monastic complex formerly ded- cities in Central Mexico in the pre-His- style under Porfirio Díaz. The city also icated to San Simón and San Judas panic period. Viceregal authorities has many museums, such as the Re- is now known as San Antonio. Visit built the colonial city in a small valley. gional Museum, Museum of Memo- former pulque-producing haciendas The state capital is now a beautiful city ry, Art Museum, the Living Museum nearby, such as the Hacienda San Bar- that preserves 16th-century buildings of Folk Arts and Traditions. Another tolomé del Monte. such as the former Convent of Nues- attraction is the Jorge “El Ranchero” tra Señora de la Asunción and from Aguilar Bullring, one of the country’s Ocotelulco the 17th century, such as the Basilica oldest, built in 1817, and now the venue ALONSO DE LOURDES MARÍA PHOTO: of Ocotlán. The latter structure com- for the annual Tlaxcala Fair held in Oc- This site was one of the major Tlax- memorates the apparition of the Virgin tober and November. caltec towns in the Late Postclassic San Bernardino Contla Chiautempan Mary in 1541 to a local native man from period (AD 1200–1521); in fact, at the Tlaxcala, Juan Diego Bernardino, and time of Hernán Cortés’s arrival, it was A textile-producing town specializ- A town renowned for its textiles. -

Inventario Del Archivo Municipal De Tetla De La Solidaridad, Tlaxcala

Inventario del Archivo Municipal de Tetla de la Solidaridad, Tlaxcala Maricela Mauricio Inventario 370 APOYO AL DESARROLLO DE MUNICIPIO DE TLAXCO, ARCHIVOS Y BIBLIOTECAS TLAXCALA DE MÉXICO, A.C. (Adabi) Javier Hernández Mejía María Isabel Grañén Porrúa Presidente municipal Presidencia Alejandro Becerril Sánchez Stella María González Cicero Secretario Dirección Amanda Rosales Bada Subdirección Jorge Garibay Álvarez Asesor vitalicio María Cristina Pérez Castillo Coordinación de Publicaciones Karla Jimena Lezama Aparicio Formación Maricela Mauricio Coordinación María Areli González Flores Asesoría Alejandro Morales Guarneros María Esperanza Hernández López Maribel Muñoz Agustina Badillo Torres Analistas ÍNDICE 5 Presentación 7 Síntesis histórica 26 Archivo 31 Fuentes 33 Cuadro de clasificación 34 Inventario Tlaxcala. Archivos. Inventario del Archivo Municipal de Tetla de la Solidaridad, Tlaxcala / Maricela Mauricio / Apoyo al De sarro llo de Archivos y Bi bliotecas de México, A. C., 2018. 56 pp.: il.; 16 x 21 cm- (Inventarios, núm. 370) 1.- Inventario del Archivo Municipal de Tetla de la Solidaridad, Tlaxcala 2.- México - Historia. I. Maricela Mauricio II. Series. Primera edición: mayo 2018 © Apoyo al Desarrollo de Archivos y Bibliotecas de México, A.C. www.adabi.org.mx Se autoriza la reproducción total o parcial siempre y cuando se cite la fuente. Derechos reservados conforme a la ley Impreso en México PRESENtaCIÓN En el 15 aniversario de Apoyo al Desarrollo de Archivos y Bibliote- cas de México, A.C (Adabi) nos congratulamos de seguir ofreciendo a nuestros lectores la colección de inventarios, resultado de la intensa y fructífera labor de rescate y organización de archivos civiles y eclesiásticos. En Adabi hemos dado prioridad a la elaboración del inventario general de los documentos de un archivo, dada la facilidad de su elaboración.